- Upgrade

- Posted

Home school

Rural Ireland has a crisis of dereliction, with numerous government policies aimed at breathing new life into thousands of old, vacant buildings. The careful transformation of one 19th century schoolhouse into a small, beautiful home shows a way forward for the sensitive, climate-conscious renovation of many of these properties.

Building: 52 m2 detached schoolhouse from 1870

Method: Retrofit with internal timber frame

Location: County Leitrim

Standard: Enerphit (uncertified)

Energy bills: €20 per month for space heating (estimate). See ‘In detail’ for more.

Seán Breathnach’s deep retrofit of a 19th century schoolhouse offers an insight into what might be done with Ireland’s extensive stock of empty stone-built buildings. Working almost singlehandedly, Seán converted a drab ruin into a high comfort home, which is beautiful both inside and out. He estimates that the entire project, including the purchase of the site, cost about €95,000 (though he stresses this is a rough estimate).

When Breathnach returned to Ireland from Canada in 2017, the carpenter and newly qualified passive house designer had a very clear idea of what he wanted to do: find a small, dilapidated structure in the west of Ireland and bring it up to Enerphit standard (the passive house retrofit standard). He found the perfect candidate in a schoolhouse perched at the top of a hill in north Leitrim.

“It dated from 1870, and it was very cheap, which was great because my budget was tiny. I got it for €33,000,” he says. “What made it perfect was the fact that somebody had already started renovating it around 2006. They’d cleared out all the old fixtures and fittings. They also re-roofed it, put on new skylights and replaced the lintels in the stone walls.”

The most surprising thing about the building was that it was bone dry inside. “The first time I walked in with a friend who lived up there, we couldn’t believe how dry it was. You’d expect everything to be covered in mould. But the roof was sound, and all the windows were broken, so there was plenty of air circulating through it.” In addition, well-draining soil and the elevated location meant that moisture tended to fall away from the site.

Breathnach had left Ireland for Canada in 2006, served an apprenticeship as a carpenter and in time became an expert in post and beam construction – what’s known simply as ‘timber framing’ in Canada. He subsequently developed an interest in alternative building systems like straw bale and other natural materials.

“The problem was that these projects could be very badly detailed. The concept could be great, but the detailing, particularly in relation to airtightness, tended to be quite poor,” he says. It was in order to redress this deficiency that Breathnach began researching the passive house standard, and ended up taking a passive designer course in Vancouver in 2017, the same year he decided to return to Ireland.

It’s warm, it’s quiet and the air quality is perfect.

Because the Leitrim schoolhouse was technically derelict, he was granted a planning exemption and was cleared to begin work. The school’s outhouse hadn’t formed any part of the aborted 2006 refurbishment and was effectively a shell: four walls but no roof. Breathnach rebuilt the walls of the outhouse, put on a roof, insulated it and moved in. This tiny (nine square metre) building would be his home for the coming months as he began work on the schoolhouse itself.

The plan was to build a new house inside the shell of the old building; a box-within-abox. The exterior walls function as a cladding material, then you have a 40 mm air gap and the interior shell is built out from there, beginning with a weather membrane and 40 mm Gutex woodfibre insulation, while 150 mm of cellulose in the stud takes care of the bulk of the insulation.

“Because this kind of build is rare, it’s difficult to know exactly how big that air gap between the stone and interior shell should be, or how many ventilation holes you need,” he says. When insulating internally, there is always a greater risk of creating a dew point for condensation, where the temperature drops suddenly between the new insulation and the old wall.

So, Bob Ryan of Earth Cycle Technologies was hired to run a WUFI condensation analysis, which confirmed the integrity of the build-up. In addition, Breathnach, who is studying civil engineering in Sligo IT, plans to conduct a full moisture assessment of the walls as part of his final year dissertation.

He also deliberately avoided using concrete as much as possible to reduce the embodied carbon of the build. There is no concrete slab, for example, and instead the beams are supported with a combination of small concrete pads and Mannok Aircrete thermal blocks.

Breathnach was able to complete the build with very little help. “You’d be surprised how much you can do on your own if you’re used to it,” he says. “I didn’t have any concrete pours, those pads were small, and it turned out that there was no roofing required at all, which was amazing. I upgraded the glass in the skylights, but that could be done from the inside. In terms of other contractors, I had a guy do the driveway, I had an electrician do his stuff, and I had help with insulation pumping and the heat pump installation.”

Homeowner and carpenter Seán Breathnach

He deliberately avoided using concrete as much as possible.

Breathnach especially praises Roman Szypura of Clíoma House, who installed the cellulose insulation, for his workmanship, and the guidance he provided on airtightness.

While the house is not Enerphit-certified, it does meet the requirements of the standard in PHPP, the passive house software. You can use one of two methods to qualify for Enerphit: either by meeting energy performance targets for the individual elements of the building (the component method), or by meeting overall space heating targets for the building.

Breathnach chose to go the component route. While in a retrofit this only requires internally insulated walls to achieve a U-value of 0.35, he chose to aim for the higher target of 0.15. This move alone cut the modelled heat demand of the building by almost half, from 48 to 26 Wh/m2/yr. The downside was that the additional insulation thickness reduced available space in what is already a small house.

This article was originally published in issue 41 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

Breathnach also makes a point about form factor in small buildings. Form factor refers to the shape of the building. It’s the ratio of the external surface area to the usable internal floor area, or treated floor area. It can also be measured by the ratio of the external surface area to the internal volume (SA/V).

Heat loss form factor, to give it its full title, is essentially a measure of how dispersed the design is. In essence, a simple, quadrilateral design is easier to heat than one which is more spread-out. However, form factor can penalise small housing units, no matter how otherwise compact.

This is from The Passivhaus Designer’s Manual edited by Christina J Hopfe and Robert S McLeod: “...buildings can have identical U-values, air change rates, window areas and orientations yet feature very different heating and cooling demands simply because of their SA/V ratio. Very small buildings (such as detached bungalows) have an inherent high surface area to volume ratio compared to larger buildings.”

Breathnach says this can make it harder for small buildings to achieve passive house certification. It can also make it harder to achieve airtightness targets, because air changes per hour — the way in which airtightness is evaluated under the passive house standard — is a measure of the proportion of the interior volume of the building passes that through the surface area in one hour. It’s not hard to see why a smaller volume could yield more air changes.

Airtightness in the walls comes via an Intello membrane, while 18 mm Smartply tongue and groove board provides airtightness in the floor. Breathnach says his detailing philosophy was based on simplicity.

“I tried to keep everything as basic as possible,” he says. “This meant minimising timber build-up at junctions and ensuring insulation in any gaps. A lot of traditional stick-framing techniques overbuild corners and openings resulting in excessive thermal bridging.”

-

The 19th century schoolhouse was gutted prior to construction

The 19th century schoolhouse was gutted prior to construction

The 19th century schoolhouse was gutted prior to construction

The 19th century schoolhouse was gutted prior to construction

-

Douglas fir for the interior frame was sourced from a local sawmill, while studwork on the inside of the walls and roof was insulated with cellulose and then covered with an Intello vapour control and airtightness membrane

Douglas fir for the interior frame was sourced from a local sawmill, while studwork on the inside of the walls and roof was insulated with cellulose and then covered with an Intello vapour control and airtightness membrane

Douglas fir for the interior frame was sourced from a local sawmill, while studwork on the inside of the walls and roof was insulated with cellulose and then covered with an Intello vapour control and airtightness membrane

Douglas fir for the interior frame was sourced from a local sawmill, while studwork on the inside of the walls and roof was insulated with cellulose and then covered with an Intello vapour control and airtightness membrane

-

Douglas fir for the interior frame was sourced from a local sawmill, while studwork on the inside of the walls and roof was insulated with cellulose and then covered with an Intello vapour control and airtightness membrane

Douglas fir for the interior frame was sourced from a local sawmill, while studwork on the inside of the walls and roof was insulated with cellulose and then covered with an Intello vapour control and airtightness membrane

Douglas fir for the interior frame was sourced from a local sawmill, while studwork on the inside of the walls and roof was insulated with cellulose and then covered with an Intello vapour control and airtightness membrane

Douglas fir for the interior frame was sourced from a local sawmill, while studwork on the inside of the walls and roof was insulated with cellulose and then covered with an Intello vapour control and airtightness membrane

-

Measuring tape showing the depth of the cellulose-insulated stud, with Intello membrane applied to the room-face.

Measuring tape showing the depth of the cellulose-insulated stud, with Intello membrane applied to the room-face.

Measuring tape showing the depth of the cellulose-insulated stud, with Intello membrane applied to the room-face.

Measuring tape showing the depth of the cellulose-insulated stud, with Intello membrane applied to the room-face.

https://passivehouseplus.co.uk:8443/magazine/upgrade/home-school#sigProId7c75bc89cc

He also tried to keep things as natural as possible. The stick-framing in the walls was rough sawn spruce from a local sawmill, the exposed interior frame and trim is Douglas fir, from the same sawmill, while the ceiling is white deal, and the floor is Scots pine.

Though he could have fitted a loft, he opted for a single storey with a cathedral roof to give the place a feeling of size and space.

Sourcing the heat pump proved one of the biggest challenges. “I had awful trouble getting anyone to even talk to me about heat pumps. I think it’s because I’m based in Leitrim, plus the fact that it was a small project,” he says. He points out that the low number of suppliers is likely to impact the government’s plans to renovate half a million homes in the next eight years.

You’ve got to think about it as investing in your own comfort and well-being.

Breathnach subsequently worked with Greentherm in Dublin, installing a Hitachi 7.5 kW heat pump, which works with a radiant tubing system, installed in the walls rather than the floor.

According to Enda Ruxton of Greentherm, the heat pump’s large size for such a small, highly insulated house was about ensuring hot water supply at all times. “People are forgetting that if you empty a 300-litre tank and fill it with cold mains water, it’s going to take you almost 15 kWh to bring to 60C.” Ruxton adds that inverter-driven heat pumps will tend to modulate down to about half of their output. “A 7 kW would modulate down to about 3.5 kW, which is just bigger than an electric immersion. And people forget about hot water recovery. If you have a few people taking showers it could take a couple of hours to heat back up. It’s the battle between energy efficiency and practicality.”

With everything specified, the construction phase proceeded remarkably smoothly. “I got lucky,” says Breathnach, “really lucky, first of all with the state of the building when I bought it, and also I didn’t hit any major snags that I couldn’t figure out. I’ve worked on so many buildings and something always goes sideways, and you go, ‘Oh right here’s another five grand down the hole because I didn’t see this coming’. That didn’t happen here, and it was down to pure luck.” The timing of the build was also fortunate.

He opted for a cathedral roof to give the place a feeling of space.

Everything was done before the current phase of building materials inflation kicked in. Breathnach moved in in October 2019, when the house was just about liveable, and continued to work on it through the summer of 2020.

“It’s been brilliant,” he says, “compared to a lot of rental houses in Ireland which are hard to heat and can have mould issues. The temperature is perfect. It’s warm, it’s quiet and the air quality is perfect.”

Including the purchase of the site, Breathnach estimates his project cost about €95,000. He can’t quite put a value on his own labour, but estimates it at something around €50,000. As such, this is probably one of the most cost-effective projects that Passive House Plus has ever featured. Between December 2020 and December 2021, his total electricity bill came to €1,099.

“A lot of people when they look at renovation, they think in terms of payback times. Maybe that makes sense with a rental property, but if it’s your own home, you’ve got to think about it as investing in your own comfort and well-being. That’s something that you can’t put a number on,” he says.

It’s interesting to note too that because the schoolhouse was originally a public building, the quality of the stonework is superior to what you usually find in dwelling houses of the same period – an important consideration for someone looking for a renovation project. Breathnach points out too that very many of our run-down town centres feature period stone buildings. In the context of Ireland’s various town centre regeneration plans, not to mention the housing crisis, his ‘box-within-a-box’ approach could offer an excellent template for refurbishing stonebuilt buildings.

“Builders often shy away from stone because it’s awkward,” he says. “But approaching the project in this way makes it far more doable, and offers a way of renovation which meets NZEB standards.”

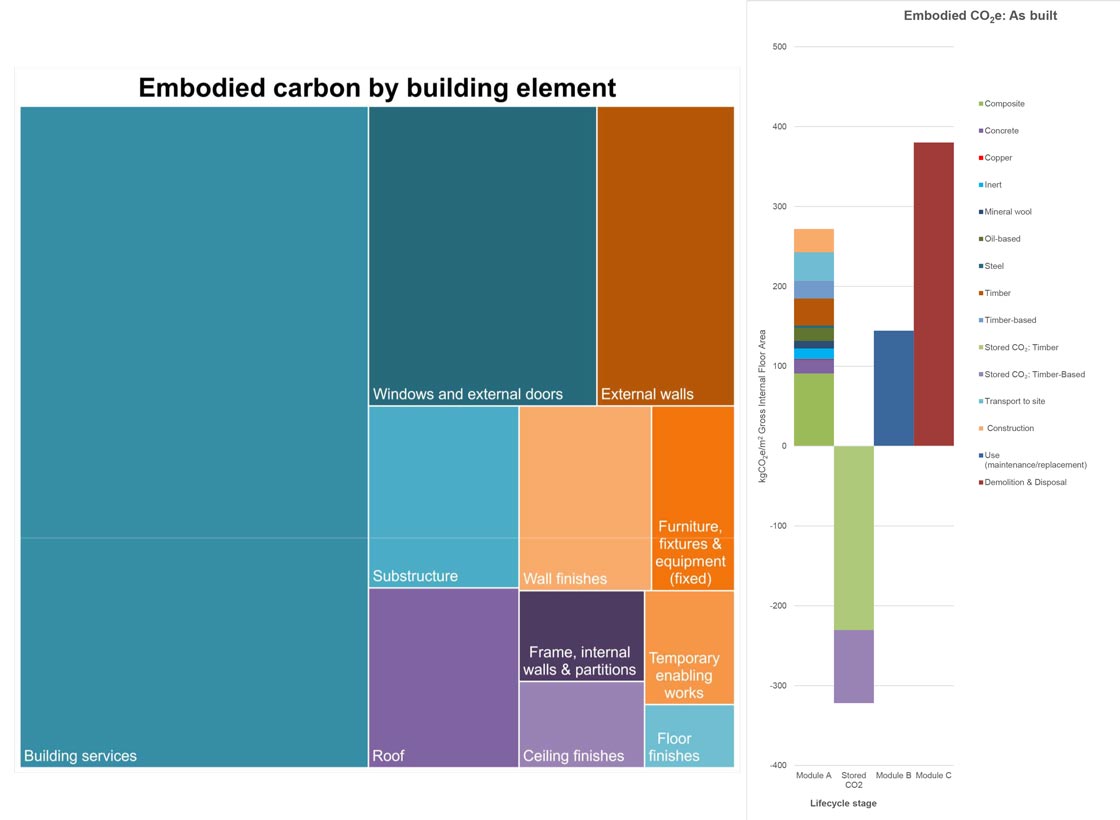

Embodied carbon

The embodied carbon of the house was assessed by John Butler Sustainable Building Consultancy using PHribbon. The scope was in accordance with the requirements of the RIAI 2030 Climate Challenge embodied carbon reporting (See our explainer on what we include in embodied carbon calculation on page 75). In this case, the calculation included virtually all works done since Breathnach acquired the property, which therefore excluded works done before Breathnach’s time, such as a new roof membrane and slates, roof window frames, and with an empty shell inside.

The total came in at 26.8 tonnes – or 415 kg CO2e/m2 gross internal area, comfortably inside the RIAI 2030 Climate Challenge target of 625. While the total may seem high given that this project is a retrofit, there is one mitigating factor in particular: the house’s very small size and high surface area to volume ratio means that each square metre of floor area carries a higher proportion of the total. If floor area is ignored, the result looks very different: the score of 26.8 tonnes is the second lowest of the four retrofit projects assessed in Passive House Plus case studies to date. Notably, the only retrofit to post a lower score, an Enerphit to a far larger house by Ruth Butler Architects in New Forest, did not include interior finishes or fitted furniture – which in Breathnach’s house make up 11.9 per cent of the total – and did not involve installing a new heating system.

As if to emphasize that point, by far the single greatest contribution to the embodied carbon score of the building is the building services, which represent 48.8 per cent of the total emissions. The vast bulk of this total comes from the heat pump, which is taken to represent over 8.7 tonnes, roughly a third of the total. (It’s important however to emphasize that even when heat pumps come with a significant embodied carbon impact, this tends to be paid back many times over in terms of emissions reductions from operational energy use.)

The heat pump data was derived from a Product Environmental Passport (PEP) by the French industry association Uniclima, a generic certificate applicable to specific air-to-water heat pump models from a number of leading heat pump brands. A health warning here: strictly speaking these values don’t apply in this case, as the manufacturer and model in question wasn’t referenced in the PEP, but the data in the PEP seemed a close analogue for the installed heat pump. As per the PEP, the heat pump was projected to have a 17-year lifespan, meaning two replacement heat pumps were included to cover the projected 50-year lifespan of the building, with both replacement units assumed to have very low global warming potential (GWP) refrigerants, given the expected impact of the EU F-Gas Regulation and Montreal Protocol. The refrigerants in the PEP were substituted for the refrigerant used in the heat pump – R410A, which has a relatively high GWP of 2088. Breathnach’s heat pump includes 2.4 kg of R410A – as the much lower GWP R32 wasn’t yet available on the market – representing over 5 tonnes of CO2e. As per TM65.1 the refrigerant leakage in the first heat pump adds up to a total of 1.75t of emissions.

The house’s Munster Joinery Passiv Aluclad windows – which have an Environmental Product Declaration (EPD) showing a 50-year lifespan – added 2.97 tonnes, while the frames of the roof windows – which were installed prior to Breathnach acquiring the property – were not calculated. The triple glazed units Breathnach fitted into the existing roof window frames added a quarter of a tonne.

In line with the RICS Whole Life Carbon guidance, emissions associated with the construction process itself were estimated based on the value of the project. Sean Breathnach, who did most of the construction himself, estimated that the total build cost would have been circa €140,000 if he had paid contractors to do the work instead, rather than the actual build cost of €62,000. The difference added almost a tonne of embodied CO2e. In line with LETI’s embodied carbon guidance, the construction process totals were divided out among the building elements according to their A1-A3 embodied carbon scores.

As per the RIBA & RIAI 2030 Climate Challenge targets, external works were calculated but not included in the main totals. If included, they would have added an estimated 3.3 tonnes of embodied CO2e.

Selected project details

Client & builder: Seán Breathnach

Passive house consultant: Earth Cycle Technologies

WUFI analysis: Earth Cycle Technologies

Heating & plumbing contractor: Ribbit Engineering

Electrical contractor: Shay Boylan

Timber (framing): Brooks Group

Cellulose insulation: Clíoma House

Wood fibre insulation: Gutex, via Ecological Building Systems

Airtightness products: Ecological Building Systems

Windows and doors: Munster Joinery

Roof windows: Velux

Entrance doors: Munster Joinery

Timber (fit-out and trim): McHale’s Sawmill

Flooring: McHale’s Sawmill

Heat pump: Greentherm

MVHR: Paul Scotland

In detail

Building type: 52 m2 detached schoolhouse from 1870. Enerphit refurbishment to near-derelict building without extension.

Location: Rural site, Co Leitrim

Completion date: September 2020

Budget: €95,000 including cost of land and property and all materials. Majority of labour not included except for electrical, groundworks, insulation and installation of heating system (though homeowner helped with these too to keep costs down). Homeowner’s labour estimated at an extra €50,000.

Passive house certification: Meets Enerphit criteria via component certification but uncertified.

BER (after): TBC

Space heating demand: 26 kWh/m2/yr

Heat load (PHPP): 10 W/m2

Primary energy demand (PHPP): 106 kWh/m2/yr

Primary energy renewable demand (PHPP): 61 kWh/m2/yr

Heat loss form factor (PHPP): 2.24 (surface area to volume)

Overheating (PHPP): 8%

Number of occupants: 1

Energy bills (after): €1,099 spent on electricity (Dec 20 – Dec 21) including all charges. Using final energy demand figures in PHPP, Bonkers.

ie suggests a cheapest available annual space heating & cooling bill for this property of €236 for this property (17.32 cent per kWh plus 13.5% VAT). Exclusive of annual standing charge of €184 and PSO levy of €52.

Airtightness (after): 0.7 ACH

Ground floor

Before: Uninsulated dirt floor.

After: Suspended timber floor insulated with 425 mm cellulose insulation. U-value: 0.09 W/m2K

Walls

Before: Solid stone wall.

After: Stone wall externally, followed inside by air gap, weather membrane, 40 mm Gutex woodfibre insulation, 150 mm cellulose in stud cavity, Intello airtight membrane and vapour control layer, 100 mm Rockwool, 12 mm plasterboard. U-value: 0.13 W/m2K

Roof

Before: Roof slates on strapping with weatherproof membrane over rafters.

After: Slates on wooden strapping over weatherproof membrane (all retained). Existing rafters as air space. Breathable membrane, 300 mm cellulose insulation in stud framed cavity, Intello air barrier, 100 mm Rockwool insulation in stud framed cavity, 19 mm wooden ceiling. U-value: 0.10 W/m2K

Windows & doors

Before: Single glazed, timber windows and doors. Overall approximate U-value: 3.50 W/m2K After: New triple glazed windows: Munster Joinery triple glazed PassiV Future Proof timber aluclad windows and doors. Overall U-value of 0.80 W/m2K

Roof windows: Velux triple glazed roof windows with thermally broken timber frames. Overall U-value: 1.0 W/m2K

Heating sytem

Before: Open fireplace.

After: Hitachi Yutaki-M 7.5kW monobloc air source heat pump, heating via wall and floor mounted radiant heating pipes. 200L split tank for domestic hot water.

Ventilation

Before: No ventilation system. Reliant on infiltration, chimney and opening of windows for air changes.

After: BluMartin FreeAir decentralised heat recovery ventilation system with extract duct from bathroom. Passive House Institute certified to have heat recovery rate of 86%.

Water: Low flow fixtures throughout.

Green materials & measures: Retention of original walls and existing roof; avoidance of concrete where possible; cellulose and wood fibre insulation; timber construction and finishes.

Image gallery

https://passivehouseplus.co.uk:8443/magazine/upgrade/home-school#sigProId966a4c6d03