- Upgrade

- Posted

Victoria Falls - 19th century home drops energy demand by 94%

This ambitious renovation and extension of a single-storey Dublin redbrick, bringing it up to an A1 rating while far exceeding the new build NZEB standard, provides a beautifully-detailed blueprint for delivering warmth, comfort, and healthy indoor air — as well as extra space and living density — in historic city centre properties.

Click here for project specs and suppliers

Building: Extensive refurbishment & extension of Victorian mid-terrace, 115 m2

Location: Dublin 8

Budget: €280,000

Standard: A1 BER rating & NZEB

ENERGY BILL FROM €34 PER MONTH (all space heating, ventilation, hot water, lighting, fans, pumps etc., but excluding plug loads)

This Victorian mid-terrace redbrick house in Dublin 8 underwent a stunning renovation and extension that was completed last year, but a near ten-year hiatus between planning permission and construction also allowed its architect to use it as a highly insightful case study in retrofitting older dwellings to the nearly zero energy building (NZEB) standard.

Owner Fiona Whelan had bought the 92 m2, single-storey house in the early 2000s and commissioned architect Daniel Coyle to draw up plans to tear down the existing, small extension (built in the 1980s) and replace it with something altogether more comprehensive, with a reconfigured layout incorporating two bedrooms, two bathrooms, and open plan living / kitchen / dining areas. The emphasis was on creating flexible and adaptable spaces, and the ability to close off or open up rooms.

The design and planning permission was granted in late 2008, but just as the boom was clearly turning to bust “we just parked it for a few years and, financially and everything, we just decided to live in the house as it was”, says Whelan.

She had forged her connection with Coyle through a project that he completed for her parents a few years previously, and they remained in touch. By the time they re-engaged in 2017, Coyle had developed expertise in energy efficient building design, having completed — with distinction — a master’s degree in energy retrofit technology at DIT (now TU Dublin) in 2015. He now lectures part-time on the college’s MSc in building performance.

Armed with this knowledge, Coyle was able to bring Whelan on board with modifications to the original 2008 design to help achieve the NZEB standard, and an A1 energy rating. “It’s probably very fortuitous, in a way, that there was that delay because if it had been built in 2008, it probably would not have achieved such a high energy performance target,” says Coyle.

In fairness, the original brief did include a stipulation that the dwelling be transformed into a “future-proofed low energy home”, but he admits there were no specific discussions on the way to achieve this, or whether it could have been done to passive house or any other standard. “These standards were less defined at the time, and perhaps we saw them then as too ambitious or difficult to achieve in a retrofit project.”

Among the more significant tweaks to the original design were to the roof and facades of the extension, so as to achieve a better balance between winter time solar gain and summer time shading, along with ambitious fabric insulation standards, airtightness, low energy heating and ventilation strategies. The old roof was a mono-pitched design, in a way that would have resulted in excessive glass on the south facade of the extension, so this was replaced by a barrel-vaulted roof with a sun-shading canopy. “We kind of realised that with a bit more knowledge and knowing that there was too much glass might expose it to the risks of overheating,” says Coyle.

The ten-year hiatus was clearly fortuitous for another reason, as the roof is by some way the most striking design feature of the whole dwelling. Although Coyle can’t recall if it was deliberate, there is a nice aesthetic synchronicity between the upper barrelvault shaped windows at both ends of the extension with the arches of the old hallway and the front porch on the outside.

For Whelan, any kind of renovation would have been an improvement on what was a very dark, cold building with little connection to the southwest-facing garden, and which was very much at the end of its lifecycle in terms of the roof finishes, interior, windows, and services.

Aside from the poorly designed original extension and a problematic layout, “my biggest problem with the house was that it wasn’t working from a heating point of view,” says Whelan. “It was freezing; just damp, dark and miserable, “adding that they were spending on average €200 to €250 per month just to try to keep the place warm. So, they were clearly receptive to new and better ways of making the renovated home as warm, comfortable and energy efficient as possible.

It’s great to be able to combine a low energy house with an attractive design.

By 2017, Whelan had accumulated a decent budget and Coyle had garnered more than enough knowledge in deep retrofits, and so they began the process of re-designing and tendering in September of that year, with construction beginning the following month. The extension and much of the back half of the original house was demolished and rebuilt and a much larger extension — spanning the length of one side of the large garden — was built, pushing the total footprint to 115 m2.

With contractor Dave Thompson of DP Building and Carpentry at the helm, the build went smoothly, despite Thompson not having a huge amount of experience in building to this standard of energy efficiency. “It wasn’t a contractor who had done passive houses or airtightness before so, as always, I thought that would be more of a challenge, if you didn’t have someone with previous experience, but actually he took it all on board very well,” says Coyle.

Dave Thompson likewise praised Coyle’s design skills, while singling out mechanical contractors Green House too, who he said “were excellent”.

What also helped were clients who had the budget and were pretty much on board all the way. “It wasn’t a project where we had to penny-pinch or cut corners, or you’re trying to explain or argue the case for a particular amount of insulation or something. I mean, that was quite easy in a way in that they were behind everything; they did appreciate [the idea of] investing in the fabric to get to a high energy standard.”

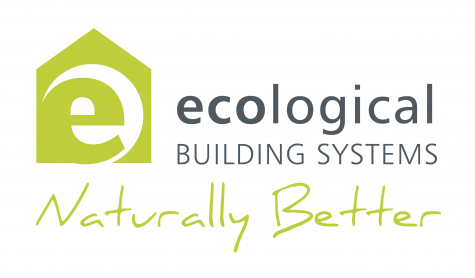

1 The extensive refurbishment underway of the mid-terrace Victorian house; 2 the existing, small rear extension was demolished, and replaced with a new extension spanning the length of one side of the large garden; 3 stainless steel angle support brackets for sliding doors / glazed screens, bolted to the edge of the floor slab, with 150 XPS insulation below DPC level; 4 underfloor heating was installed throughout the house, above the Xtratherm PIR insulation; 5 the extension walls feature 200 mm KORE EPS as part of a Webertherm EWI system, on 215 mm Roadstone Thermal Liteblock concrete blockwork; 6 the new pitched roof, with Intello membrane and Velux top-hung triple glazed roof windows; 7 Remmers iQ-Therm capillary-active internal insulation; 8 the solar PV array feeds directly into the house’s general electricity supply, with any excess electricity being first diverted to the heat pump for hot water production; 9 brickwork on the front facade repointed with lime mortar.

As well as the fabric upgrades, Coyle also specified – in line with NZEB and passive house design principles – triple glazing, high levels of airtightness, an exhaust air heat pump and solar PV, not to mention passive solar gain strategies and the elimination of thermal bridges.

But rather than use passive house modelling tools (PHPP) to come up with the appropriate mix of measures, Coyle used DEAP, Ireland’s standard building energy rating and Part L assessment tool. “Although I had done some training in PHPP and have a fairly good understanding of passive house design principles, I am not a certified passive house designer. I have much better working knowledge of DEAP as a design tool.”

Furthermore, he adds that although perhaps less rigorous, it’s a far simpler tool for the calculation of energy performance and negated the need for an external passive house consultant and the costs associated with that.

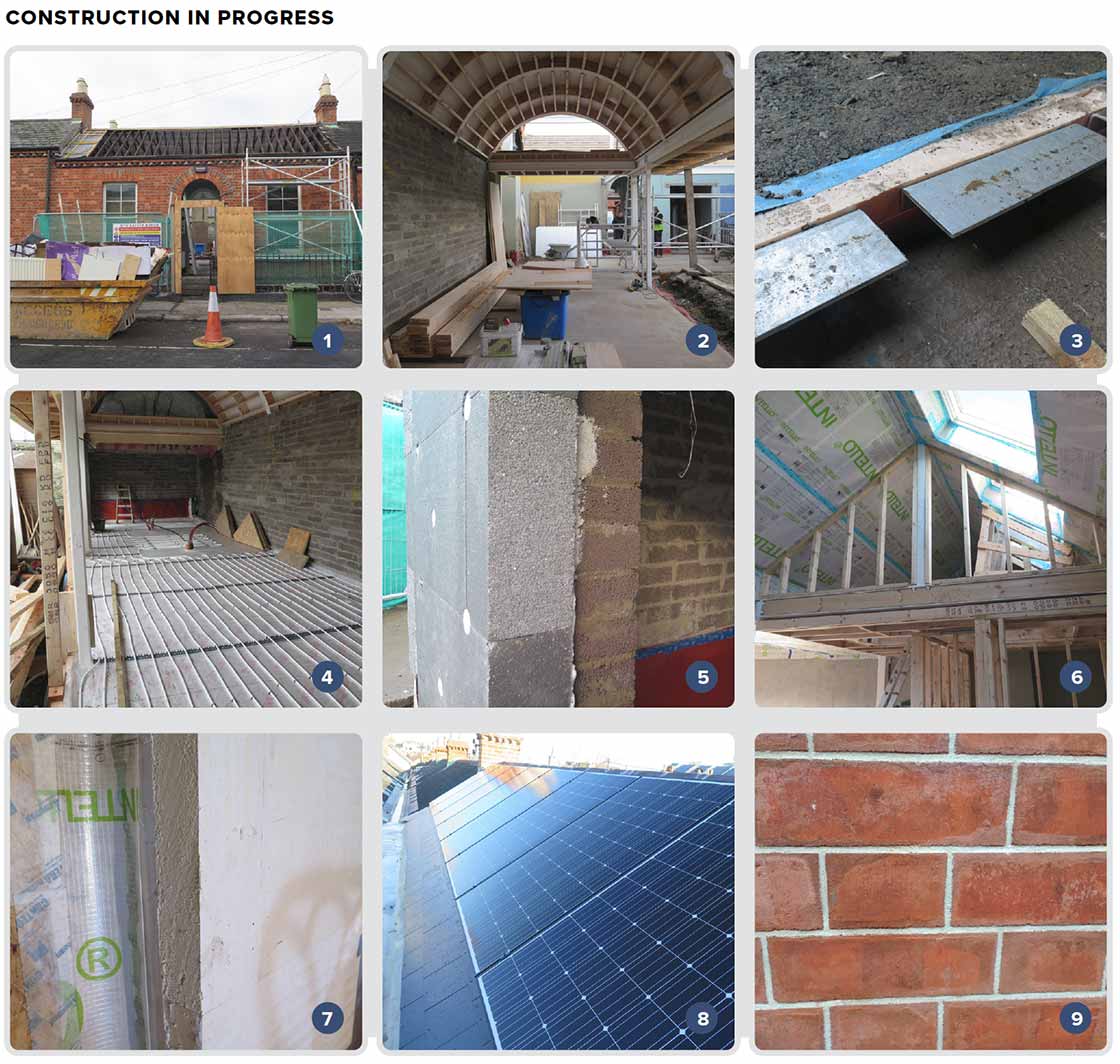

(above) 3D floor plan of the finished dwelling, with bedrooms in the original part of the dwelling (at right) and kitchen and dining areas in the new extension (at left); (below) graphic sequence showing demolition of the old extension and construction of the new one.

This article was originally published in issue 33 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

“And at the end of the day DEAP, and the BER rating system, is the de-facto compliance tool for new build and major renovations in Ireland, so this gives it a certain advantage.” He does say, though, that if he was approaching it again, he would consider going for passive house certification.

By the end of the stripping out and demolition, there wasn’t that much left of the original fabric of the house besides the front two rooms and adjoining hallway. The solid brick front walls had to be repointed with lime, but some of the existing plaster was simply repaired, because it provides a good level of inherent airtightness, before being dry lined internally.

Insulating walls internally always presents a moisture risk, because it can create a ‘dew point’ for condensation between the old wall and the new insulation, but there is also an extra risk with old brickwork, because it is quite porous to rain coming through from the outside. To mitigate this risk, Coyle specified Remmers iQ-Therm internal insulation, a capillary-active, diffusion open and breathable PUR foam insulation board designed for use on conservation projects, which should enable the wall to dry out internally.

There is also a lime parge coat to the inside face of the brick wall, and lime plaster on the inside of the iQ-Therm too (lime is more breathable than traditional cement), while the base of the walls were injected with a rising damp barrier. Coyle did not undertake a condensation risk analysis, but feels that given the limited area and height of the wall, the overhanging eaves, its sheltered aspect, the sunny south-east orientation (which will help the wall to dry out), and the modest U-value achieved by internal insulation (0.32), the risk of condensation and damp is low.

A cost effective retrofit

Another point of interest here is that Coyle was able to use this house as a case study in extrapolating from the overall budget the specific costs of the fabric and systems upgrades required to deliver an A1 energy rating, which he estimated at €60,000 of the total budget of €280,000 (or €75,000 if you include VAT and fees).

Coyle also estimated the annual savings in energy costs at some €4,000 a year.

It’s important to note these figures are the cost of upgrading this house from a theoretical BER rating of G right up to A1. In other words, this is comparing the finished and remodelled A1-rated house, including the extension, with the exact same design and layout but “reverse-engineered” with no energy efficiency measures at all.

In practical terms this means no insulation, very poor airtightness, single glazed windows, a non-condensing gas boiler (70% efficiency) without controls and no ventilation – other than via infiltration. It also assumes that the occupants would have fully heated the G rated house, rather than that simply made do with colder indoor temperatures, so it is most likely an overestimate.

In reality, of course, any extension built in 2017 would legally had to have met the 2011 version of Part L of the building regulations, so the ‘extra over’ capital cost would be the difference between achieving that standard and an A1 rating, rather than the difference between getting a G and an A1. So, the real ‘extra over’ cost of going to A1 versus meeting minimum requirements would be significantly less, but the savings on energy bills would be less, too.

“If you are asking the question of whether a deep retrofit such as this is cost-effective, or a good financial investment, then really you need to do a proper life cycle cost calculation and investment appraisal, as opposed to just a simple payback calculation — which [in this case] would be 19 years — says Coyle.

“This would mean taking into account fuel inflation, interest rates etc and over a 30-year plus investment time frame.” But even this is without considering ‘co-benefits’ such as reduced healthcare costs from living in a warmer, more comfortable home with good indoor air quality.

Coyle also monitored the energy usage costs over the first 12 months of residency, which worked out at €480 for space heating, hot water, ventilation and lighting, but not including plug loads (see the ‘In detail’ panel for more).

This is some €120 more than the DEAP estimate, but he says this gap can be explained by commissioning issues with some services, including adjustments to thermostat and heat pump settings, and some drying out of the wet plastering, but also the discovery that the building’s large solar PV array was not working for the first three months. The array feeds now directly into the house’s general electricity supply, with any excess electricity being first diverted to the heat pump for hot water production.

Fiona Whelan says that when she moved back in May 2018, the underfloor heating was never turned on all the way into the winter of that year. “I kind of did think around December time when I didn’t feel any kind of heat underfoot, was this even working? Anyway, we carried on through the winter and then we were told the thermostats were incorrect, and so there was actually no heating, but because the house was so insulated it actually wasn’t too bad.

You know, we didn’t feel the lack of it.” The project was not grant-funded, as SEAI’s PV and heat pump grants were not available at the time, and Coyle did not think it would qualify for external wall insulation grants. SEAI’s deep retrofit scheme was also just getting off the ground in 2017, so if it was being undertaken today, there would be significantly better financial support available for a retrofit like this.

It’s worth noting that Coyle didn’t specify a full mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR) system, but rather an exhaust air heat pump solution from NIBE, which he described as a hybrid of MVHR, demand-controlled ventilation (DCV), and an air source heat pump, which he says is ideal for a small but very thermally efficient and airtight house. The exhaust air system also requires no outdoor unit, making it ideal for retrofitting in small, urban gardens.

Overall, the house scores impressive marks for sustainability: it reuses an existing historic structure, is modestly sized, and right in the middle of an urban centre. And it successfully reconciled the conflict between respecting the original building’s architectural value and producing a contemporary home, all while achieving near perfection in energy performance terms.

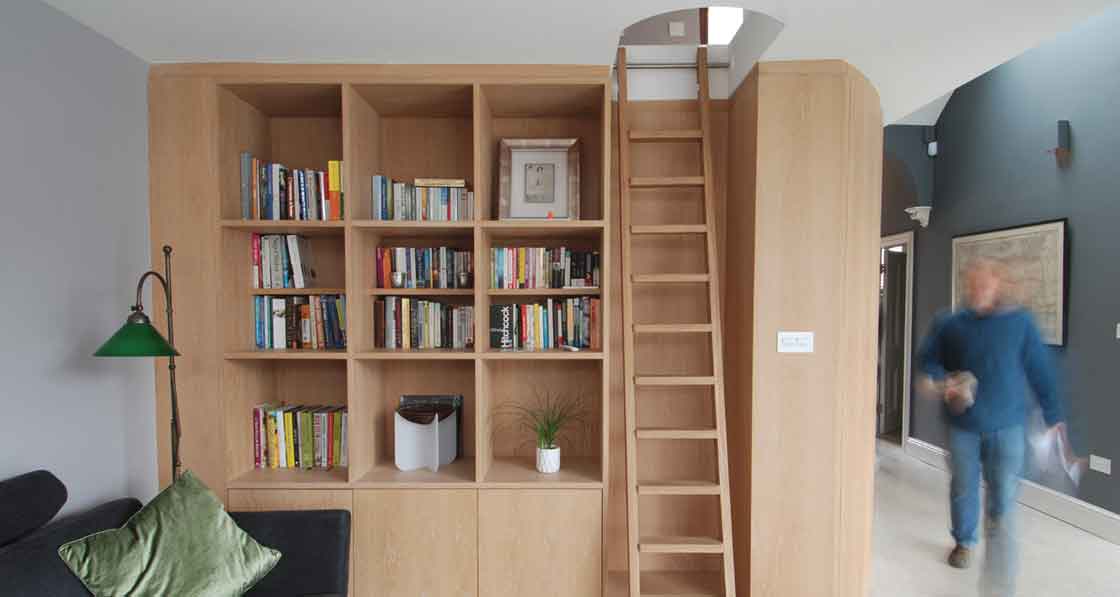

Coyle is particularly pleased that the renovated house is performing as an ultra-low energy home, but also remains a nice place to be. “It’s great to be able to combine a low energy house with an attractive design, because sometimes you can feel like the passive or the low energy aspects of a house can be at the expense of the things that make it a nice, functioning space.”

With all this, it’s no surprise to hear how much Fiona Whelan loves their home now, particularly the warmth and the connection to the garden.

“I absolutely just love getting home and to just sit there at the back and look at the garden come rain hail or shine, because it’s floor-to-ceiling glass and it’s kind of in the garden, and it’s just magic. I don’t know what to say, except I’m just the luckiest person in the world.”

Selected project details

Client: Fiona Whelan

Architect: Daniel Coyle Architects

Civil engineer: Lohan & Donnelly Engineers

Project management: Daniel Coyle Architects

Main contractor: DP Building & Carpentry

Quantity surveyor: Modia Consulting

Mechanical contractor: Green House

Electrical contractor: Niall Lynch Electrical Services

Airtightness tester: Evolved Energy

EPS insulation: KORE

Internal insulation: Remmers, via Conservation Technology

Mineral wool insulation: Rockwool

PIR insulation: Xtratherm (now Unilin)

Airtightness products: Ecological Building Systems

Alu-clad windows & doors: Vindr VS

Timber sash windows: McNally Joinery

Interior fit-out: Wabi-Sabi

Concrete polishing: P-Mac

Heat pump: Unipipe, via Green House

Solar PV: Green House

Wood burning stove: Morso, via The Stove Depot

In detail

Building type: Mid-terrace Victorian house dating from c. 1890. Comprehensively refurbished with new single-storey rear extension, total floor area 115 m2.

Location: Dublin 8

Budget: €280,000 (excluding VAT, interior fit-out, garden works & professional fees). Completion date: April 2018

Passive house certification: None, PHPP analysis not carried out

INDICATIVE BER

Before: F BER (433 kWh/m2/yr)

After: A1 BER (24 kWh/m2/yr)

MEASURED ENERGY CONSUMPTION

Before: N/A

After: Total annual measured energy consumption for first year of occupancy was 5,048 kWh (this is an all-electric house). But this total includes an estimated 3,050 kWh of appliances / plug-loads (calculated using PHPP electricity worksheet). Balance of energy consumption for all heating, hot water, ventilation, fixed lighting and auxiliary loads (fans, pumps etc.) is therefore 1,998 kWh. Equates to 17 kWh/m2/yr. Based on 1 year’s utility bills actual consumption (April 2018-April 2019).

ENERGY BILLS:

Before: N/A

After: €480 including VAT (April 2018-April 2019) electricity costs for heating, DHW, ventilation, auxiliary and fixed lighting (excludes plug-loads), or €40 per month. Dual rate meter installed. However, Daniel Coyle expects this will reduce to €30 per month now that PV & thermostat issues have been sorted out. Fiona Whelan also estimates that she spends €50 per year on wood for her stove (€4 pm).

AIRTIGHTNESS (AT 50 PASCALS)

Before: N/A

After: 1.8 m3/hr/m2 at 50 Pa

Thermal bridging: Combination of calculated Psi-values and ACDs used. Calculated Y-value of 0.04.

GROUND FLOOR: Before: Uninsulated concrete floor U-value: 0.42 W/m2K After New concrete floor (exposed polished concrete floor) insulated with 150 mm Xtratherm PIR insulation. U-value: 0.10 W/m2K

WALLS

Before: Solid brick / block walls with no insulation. U-value: 1.76 W/m2K

After: 230 mm brickwork (repointed with lime mortar), lime plaster, 80 mm iQ-Therm insulation, 15 mm lime plaster finishes. U-value: 0.32 W/m2K

ROOF

Before: Sloped with mineral wool insulation. Roof slates to sloped areas and torch on felt to flat roof areas externally. 50 mm mineral wool insulation on the flat between roof joists, plasterboard ceiling internally. U-value: 0.67 W/m2K

New pitched roof: Slates, on wind-tight layer, 220 mm mineral wool between joists, Intello Plus, 62.5 mm Xtratherm PIR. U-value: 0.12 W/m2K

EXTENSION

Extension floor: New concrete floor (exposed polished concrete floor) insulated with 150 mm Xtratherm PIR insulation. U-value: 0.10 W/m2K

Extension walls: Webertherm EWI system: 15 mm acrylic render, on 200 mm EPS (graphite), on 215 mm Roadstone Thermal Liteblock concrete blockwork, on 12 mm sand-cement plaster parging (airtight layer), on 50 mm Rockwool MW insulation, on plasterboard and skim U-value: 0.12 W/m2K. XPS below DPC level. 50 mm Xtratherm insulation on the upstands and at window reveals.

Extension roof: Zinc standing seam roofing, on plywood, on 50x35 mm battens/counter battens, followed underneath by breathable roofing underlay, 250 mm timber joists fully filled with mineral wool insulation, Intello Plus airtight membrane / VCL, 50 mm insulated service cavity (mineral wool), 12.5 mm plasterboard ceiling. U-value: 0.13 W/m2K

WINDOWS & DOORS

Before: Single glazed, timber windows and doors. Overall approximate U-value: 3.50 W/m2K

New triple glazed windows: Alumil aluminium glazed screens / sliding doors, with thermally broken frames (outer frames embedded in EWI layer), triple glazed (low-e, soft-coat, argon gas filled units, Ug=0.6 W/m2K). Overall average Uw value of 0.85 W/m2K

Roof windows: Velux top-hung triple glazed roof windows. Overall U-value: 1.1 W/m2K

HEATING SYSTEM

Before: +15-year-old gas boiler & radiators throughout entire building.

After: NIBE F730 whole house extract ventilation / exhaust air heat pump. Space heating efficiency: 354%, domestic hot water efficiency: 206% (Ecodesign Data). Underfloor heating throughout house (and two bathroom towel radiators). Secondary / back-up heating provided by Morso 5660 wood-burning stove, with external air supply for combustion, 88% efficiency.

VENTILATION

Before: No ventilation system. Reliant on infiltration, chimney and opening of windows for air changes.

After: NIBE F730 whole house extract ventilation / exhaust air heat pump. Electricity: 12 m2 (8 panels) solar photovoltaic array with average annual output of 2 kW.

Image gallery

-

1

1

1

1

-

2

2

2

2

-

3

3

3

3

-

3D VIEW - Construction

3D VIEW - Construction

3D VIEW - Construction

3D VIEW - Construction

-

3D view - front

3D view - front

3D view - front

3D view - front

-

3D view - front

3D view - front

3D view - front

3D view - front

-

3D view - rear

3D view - rear

3D view - rear

3D view - rear

-

3d floor plan

3d floor plan

3d floor plan

3d floor plan

-

4

4

4

4

-

5

5

5

5

-

6

6

6

6

-

7

7

7

7

-

Plans - before and after

Plans - before and after

Plans - before and after

Plans - before and after

-

Raymond Street_GROUND FLOOR 3D PLAN

Raymond Street_GROUND FLOOR 3D PLAN

Raymond Street_GROUND FLOOR 3D PLAN

Raymond Street_GROUND FLOOR 3D PLAN

-

nZEB Design - Design Principal

nZEB Design - Design Principal

nZEB Design - Design Principal

nZEB Design - Design Principal

https://passivehouseplus.co.uk:8443/magazine/upgrade/victoria-falls-19th-century-home-drops-energy-demand-by-94#sigProId9d99a030c8