- Upgrade

- Posted

World class passive social housing

Simultaneously tackling fuel poverty and climate change requires drastic action on deep retrofitting the existing housing stock – and fast. Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown’s deep retrofit and renovation of Rochestown House may be Ireland’s most significant retrofit to date – a fact reflected in the project picking up the sustainability award at the 2017 Irish Architecture Awards.

Click here for project specs and suppliers

Build method: Externally insulated masonry

Location: Sallynoggin, Co. Dublin

Standard: Certified Enerphit

Completed: 2016

Budget: €3.5m

€260 estimate for space heating, including €110 usage plus €150 of standing charges

Two years ago, Rochestown House, a seventies era social housing apartment block in Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin was beginning to fall into disrepair. The council was faced with three choices. Tear it down and start again, do enough to maintain it, or refurbish.

“It was getting to a stage where the block was unrentable,” says Sarah Clifford, project architect with Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council. “The council couldn’t move anyone in because of the condition of the units. They were damp, there was no one on the top floor because we had problems with the roof. All of the heating pipes were on the roof; they were circulating in the open air before they dropped down to the units, which reduced the efficiency of the heating, making running costs high. Something had to be done.”

At the same time, passive design specialists, MosArt got in touch with the county council to talk about the Passive House Institute’s Europhit programme. Europhit aims to promote and support step-bystep Enerphit projects in a variety of ways, including the provision of certification schemes and market incentive programmes. MosArt was looking for Irish case studies to participate in the programme, in return for which the council could avail of free passive house design consultancy.

Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council has of course been at the forefront of sustainable construction for years. Just last year, the local authority passed a motion that all new buildings be built to passive standards or equivalent. The decision to include Rochestown House in the Europhit project was very much in keeping with that ethos. Mariana Moreira of MosArt came on board as passive house consultant and the design team set to work.

“The existing building was very poor on all fronts,” says Moreira. “Very cold in winter, very expensive to run, the existing fabric had no insulation whatsoever. The air quality was very poor too – windows had to be kept open all the time to keep fresh air circulating.” The layout of the existing apartments was also outdated – all thirty-four units were bedsits. Sarah Clifford explains that in the context of the council’s housing policy, Rochestown House was aimed at downsizers. If the project was to succeed, it would have to provide an attractive alternative to tenants in larger houses, in order to free those up for families. The units therefore, would have to get bigger.

After exploring a number of possibilities, the design team decided that the best course of action was to go up, to retain the existing footprint and add a third storey. This would give sufficient space to open up the layout and provide more generous apartment sizes. At the end of the project, the team would end up 34 apartments – exactly the same number they had started with.

In order to keep the structure lightweight and stay within engineering constraints, aerated blocks were chosen to form the new third storey structure, together with a lightweight metal deck roof.

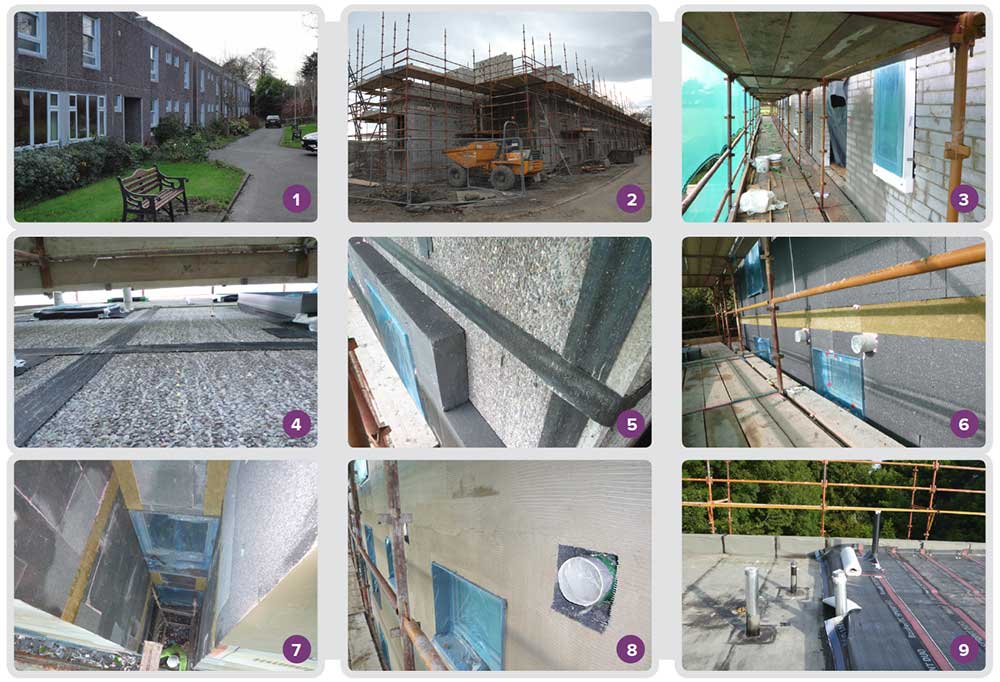

1 The Rochestown House flats prior to the refurbishment; 2 aerated concrete blocks were chosen to form new build elements, including a new third storey that allows for more generous apartment sizes; 3 new triple-glazed windows were installed outside the masonry layer so that the external insulation could wrap around them, and help prevent thermal bridging; 4 the airtightness layer was moved to the outside of the structure by taping the joints of the existing concrete panels, then extending that tape up onto the aerated blocks in the new floor; 5 Aerobord platinum EPS external insulation being fitted to the original concrete panel walls; 6 & 7 the new window frames visible here in the external insulation layer, including Rockwool fire breaks; 8 openings for exhaust and supply intakes for the new Zehnder heat recovery ventilation system, seen here prior to being insulated and airtightened; 9 installation of the Bauder bitumen roofing membrane.

Arriving at an optimal airtightness strategy took a lot of thought and discussion. The team first explored the possibility of keeping the airtight layer on the inside of the structure, but the more they learned, the more difficult that option appeared.

The external wall of the old part of the building was comprised of concrete panels. By taping the joints of these panels, then extending that tape up onto the aerated blocks in the new floor, the airtightness layer was moved to the outside of the structure. This process was completed with the addition of a screed and a scud coat onto the aerated blocks.

“That completed the envelope,” says Clifford. “With a building of that size, there was an awful lot of M&E, but by keeping the airtightness layer outside, the workers inside didn’t need to worry about puncturing membranes and compromising the layer.”

This article was originally published in issue 23 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

The lack of any preservation order on the 70s era, pebble-dashed finish meant that the design team could wrap the building in external insulation, creating an even finish across new and old structures. A timber louver designed into the third floor facade meant that the thickness of the EPS had to be reduced in some areas. Mariana Moreira says that while this feature created a thermal bridge, the passive house software – PHPP – calculated that it could be borne without breaching any of the Enerphit thresholds, or without opening the structure up to condensation and mould growth risks.

Getting ventilation right also posed particular challenges in a building of this size and type.

“We went through several options with the mechanical engineering consultant,” says Moreira. “We first looked at three centralised ventilation systems that would be installed over the new storey.” There were a few problems with this solution however. Ceiling heights were low, making it difficult to find space for ducting in overhead voids. In addition, using a dispersed ducting system would have required the installation of a high number of fire dampers, which would have generated a significant maintenance burden. The engineers were also concerned about the installation of heavy equipment on the roof of the building, not to the mention the added safety measures that would be necessary to access the equipment at that height.

Ultimately, the design team chose to install separate mechanical heat recovery ventilation units in every apartment. Each system is held in a lockable store in each apartment; filter changes and maintenance are the responsibility of the maintenance contractor. The only control confronting the tenants – many of whom are quite elderly – is the thermostat on the wall.

Mechanical contractor MPH brought an MVHR commissioning expert from Zehnder in the UK over for pre-commissioning guidance, to ensure the system was meeting the design parameters in terms of flow rates and temperature differentials, and hired an independent company to commission the systems.

The building is heated by a Dachs gas-fired condensing combined heat and power plant – which generates 5.5 kW electricity which is used to power lighting in the landlord areas, and a by-product of 14.8 kW of heat which is used for domestic hot water and – if ever required – space heating. The system is linked to a 500L thermal store, and is supported by three Remeha condensing gas boilers, if needed. If there’s no demand for hot water and the thermal store has reached its set temperature, the CHP plant – which was sized for the base thermal load – switches off.

Tenant David Falconer moved into one of the apartments on the south east facing aspect of the building just over a year ago, having come from a thirty-year old apartment building in Sandycove. So far, he’s lived through one winter in Dún Laoghaire, and says that he hasn’t yet had to turn on the heating. “There’s been no need for heating at all. The side of the building we’re on faces the south east, there’s so much insulation, and the windows are so good that even a little sun – hazy, patchy sun – is sufficient to warm up the apartment. It’s never been below 20 degrees – it’s as warm as toast.” There is a downside however, and that’s overheating.

“In summer, we have had great difficulties with heat. On one day in May, we had 27.3C inside our apartment, and it was uncomfortably hot on quite a few days in summer.” There are no shading or other features to mitigate this problem, so Falconer has installed Venetian blinds and bought fans for bedroom and living room areas. When we spoke over the phone – on a mild September morning – the temperature in the living room was above 24C.

An estimate of heating & hot water costs

What’s the net effect of the energy saving efforts at Rochestown House in terms of running cost reductions? While the scheme consisted of 34 units before and after the upgrade, a direct comparison is rendered impossible by the fact that the renovated building was increased by a storey, with the existing 34 bedsits replaced by 34 larger apartments.

While the results of ongoing monitoring were unavailable for this article, a quick analysis by Passive House Plus suggests that a typical 43.7 sqm apartment at Rochestown House would be using just under 1100 kWh of energy for space heating annually, based on the calculated space heating demand of 25 kWh/m2/yr. It’s tricky to convert that into an estimated annual cost, because of the way energy bills are typically broken down for district heating.

In the absence of data from Dun Laoghaire-Rathdown, Passive House Plus took price data from a private apartment scheme in Dun Laoghaire heated with district heating, billed through SnugZone, which includes a cost per unit of less than 10C per kWh, in addition to a daily standing charge of 93C, or an annual figure of €339. But that is levied for a service including space heating and domestic hot water use. At Rochestown House, the calculated space heating demand of 25 kWh/m2/yr is accompanied with a domestic hot water demand of 32 kWh/ m2/yr. Without the standing charges, the calculated space heating and domestic hot water costs work out at €109 and €138 respectively, or a total of €247. The reference standing charge more than doubles that, bringing the total to €587, or €260 for space heating and €327 if the standing charge is divided proportionately. It’s worth noting that the real space heating figure may be lower, if the zero heating use claim of the tenant interviewed for this article is indicative.

The opening sections of the windows are quite small, and because his apartment faces away from prevailing winds, it is difficult to introduce any natural air movement into the living room or bedroom.

The passive house software does evaluate overheating risk. In order to meet Enerphit criteria, the internal air temperature should not climb above 25C any more than 10% of the time during the year. In Rochestown House, the analysis concluded that there was actually zero risk of overheating, that the temperature would not move above 25C at any time. The issue here however is that the software calculates a result based on the whole building rather than on each individual housing unit. The overheating risk in a number of individual apartments was not identified therefore during the planning stages.

Sarah Clifford says that the county council is aware of the problem with a small number of the apartments on the south east side of the building and is monitoring the issue. It’s also worth noting that despite the fact that PHPP failed to capture the overheating risk in individual units, overheating risk is at least captured by the software. Building regulations have nothing to say about what has become an increasingly important issue in low energy building – there’s no target set in terms of maximum temperatures that a building must be designed not to exceed.

Selected project details

Client & architects: Dún Laoghaire- Rathdown County Council

M&E engineer: Ramsay Cox Associates

Civil / structural engineer: Hanley Pepper Associates

Passive house consultants: MosArt

Fire consultant: John A McCarthy Fire Safety Consultant

Main contractor: Manley Construction

Quantity surveyors: Walsh Associates

Mechanical contractor: MPH Mechanical Plumbing Heating Ltd

Electrical contractor: D&N Group Ltd

Airtightness tester / consultant: Advanced Airtight Solutions

Ventilation system commissioning: SIBS Group

External insulation system: Baumit

EPS insulation: Kingspan Insulation

External insulation contractor: EcoClad

Floor insulation: Ballytherm

Roof system: Bauder

Additional roof insulation: Rockwool

Windows: Pozbud, via Carroll Joinery

Curtain walling and external doors: Reynaers, via Carroll Joinery

Thermal breaks: Partel

Thermal blocks: Quinn Building Products

Heat recovery ventilation: Zehnder, via Versatile

Condensing gas boilers: Eurogas

District heating consumer units: Danfoss

CHP: Glenergy Ltd

Airtightness products: Alfa, via Proline Hardware

Flooring: Polyflor

In detail

Building type: 1,856 sqm (TFA) masonry block of 34 social housing apartments, externally insulated & retrofitted to the Enerphit standard.

Location: Sallynoggin, Dún Laoghaire, Co Dublin.

Completion date: 2016

Budget: €3,519,500

Enerphit certification: Certified

BER

Before: F to G (407 to 616 kWh/m2/yr)

After: B2 to A3 BER (56-110 kWh/m2/yr)

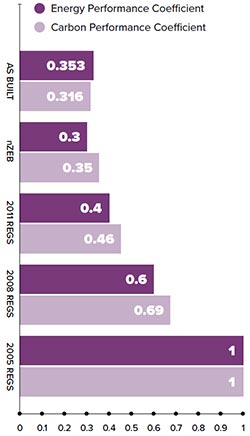

Energy performance co-efficient (EPC): 0.353 (new build only)

Carbon performance co-efficient (CPC): 0.316 (new build only)

SPACE HEATING DEMAND

Before: 354 kWh/m2/yr

After: 25 kWh/m2/yr

HEAT LOAD

Before: 109 W/m2

After: 11 W/m2

PRIMARY ENERGY DEMAND (PHPP)

Before: 682 kWh/m2/yr

After: 92 kWh/m2/yr

Primary energy renewable (PHPP): 82 kWh/m2/yr

Heat loss form factor: 2.01

Overheating (PHPP): 0% (of hours above 25C)

Annual heating costs (calculated): €109 of space heating use and €339 standing charge for heating and hot water service, based on typical apartment size of circa 43.7 sqm, taking indicative costs from SnugZone (unit cost of 9.976c per kWh, and standing charge of 93.07c per day.

AIRTIGHTNESS (AT 50 PASCALS)

Before: 5.0 ACH

After: 0.78 ACH

Upgraded walls: Original 232mm thick concrete panel walls externally insulated with Baumit system including 200mm / 250mm Aerobord Platinum EPS insulation. U-value before upgrade: 3.75 W/m2K. U-values after: 0.12 / 0.15 W/m2K

New walls: 215mm aerated concrete block externally insulated with Baumit system including 150mm or 200mm Aerobord Platinum EPS. U-value: 0.13 / 0.16 W/m2K

New roof: Bauder flat metal deck roof insulated with 150mm phenolic insulation and 50mm Rockwool acoustic insulation. U-value: 0.13 W/m2K

Ground floor: New floor areas featuring 150mm concrete slab with 120mm Ballytherm PIR insulation underneath.

U-value: 0.176 W/m2K. Existing uninsulated floor areas with 150mm concrete slab only. U-value: 4.3 W/m2K

Windows

Before: Double glazed PVC windows with overall U-value of approximately 1.4 W/m2K New triple glazed windows: Pozbud Passive Ultima, thermally broken timber-framed windows with Aerogel insulation and aluminium cladding externally. Vitrotherm triple glazing with argon fill and g-value of 64%. Overall U-value: 0.99 W/m2K

HEATING SYSTEM

Before: Oil-fired district heating. All plant replaced in upgrade.

After: District heating system, fed from the central plant room at ground floor level, with each unit having a district heating station with local control of heating circuit and instantaneous generation of hot water via a plate heat exchanger. Heating provided via a Dachs gas condensing micro-CHP unit – 5.5 kW electrical, 14.8 kW thermal, up to 99% efficiency in condensing mode, supported by three high-efficiency Remeha Quinta Pro 90 kW condensing gas boilers, linked to a 500L buffer tank. Danfoss VMTD-F single plate heat exchanger units provide instant hot water and space heating to each apartment. On the return from each radiator there’s a valve which throttles the flow rate down if the return temperature exceeds 50C to enable the condensing gas boilers to operate in condensing mode. Each apartment has a Danfoss heat interface unit including an energy meter.

VENTILATION

Before: No ventilation system. Reliant on infiltration, chimney and opening of windows for air changes.

After: Zehnder Comfoair 180 mechanical ventilation with heat recovery system to each apartment, externally accessible for maintenance. Passive House Institute certified heat recovery of 82%, and automatic summer bypass.

Image gallery

-

Location map

Location map

Location map

Location map

-

Proposed floor plans

Proposed floor plans

Proposed floor plans

Proposed floor plans

-

Proposed elevation

Proposed elevation

Proposed elevation

Proposed elevation

https://passivehouseplus.co.uk:8443/magazine/upgrade/world-class-passive-social-housing#sigProIdf529e7eeb2