Taking Part

Based on past form, the Department of the Environment officials could be forgiven for bracing themselves for a construction industry backlash in response to the proposed changes for Part L of the building regulations which aim to both improve energy efficiency and reduce carbon emissions by 40%, whilst also introducing mandatory renewable energy and air tightness requirements. Jeff Colley outlines why, for reasons of self interest alone it’s very much in the industry’s interests to embrace the new regulations rather than attempt to resist change.During the construction boom years over the last decade or so, record breaking levels of house building took place to meet a feverish demand for new homes, fed in many cases by a prevailing attitude that investing in property would result in exponentially rising capital appreciation. In this market, many people were essentially panic-buying property with little regard to general standards of workmanship, out of a fear that if they held off from making the purchase, prices would continue to rise, resulting in a missed investment opportunity, and even denying people the right to own a home.

It should come as no surprise that, given such extraordinary market conditions, the construction industry would invariably disapprove of any regulatory requirement to improve energy performance standards in buildings. To put it simply, people were buying anything that the industry could throw at them, and didn’t need the incentive of higher sustainability standards, for instance, to encourage them to buy.

However times have changed, and rapidly, to the extent that higher sustainable building requirements could be exactly what the industry needs, whether it knows this or not.

The impacts of a changing energy landscape should be central to the industry’s thinking whilst it digests the implications of the new Part L. The boom years were fueled by the availability of cheap, plentiful global fossil energy resources, more than sufficient to meet a steadily growing international demand. However, over time demand has increased to huge extents internationally, led by rapidly emerging economies such as China and India. This unprecedented demand led to oil prices passing e82 per barrel for the first time in history in late September in spite of major concerns about the economic consequences of the failure of the US sub-prime mortgage market. All of a sudden, a view formerly only associated with conspiracy theorists and eco fantasists - that the world has either reached or is about to reach the peak rate of extraction of oil and gas - has moved from the margins into mainstream political, economic and social discourse, and with good cause.

In terms of economic discourse, how long will it be before the banks, with thousands upon thousands of mortgage holding clients currently facing negative equity, rue the fact that previous governments didn’t insist on higher energy performance standards for homes built during the boom years? As mortgage holders come under pressure from rising interest rates and increasing energy costs, they may struggle to make ends meet. In many cases—in particular during colder months—many people will be naturally inclined to pay their heating bill first and find it difficult to service their mortgage. Unable to make the repayments, they may be forced to sell their home or hand back the keys to the banks, facing negative equity. This could leave the market awash with energy-intensive homes, serving to further undermine consumer confidence amongst a public rapidly becoming concerned about the cost and security of energy supply, and becoming familiar with Building Energy Ratings (BERs) as a mechanism of judging a property’s viability as an investment.

In addition, a palpable sense of eco guilt has become evident in many Irish people as they start to accept the impact their day to day actions and decisions have on global climate. Ordinary Irish people, it seems, are now of a mind to look at ways of reducing energy consumption and carbon emissions. It follows that a higher BER will, in many cases, help to rebuild consumer confidence that a particular home is worth buying.

With market conditions emerging on these lines, the proposal to improve Part L of the building regulations is compelling, and is exactly what the industry needs. However, the consultation process will invariably see some negative submissions, with the usual arguments being peddled; that the proposed increases are too onerous; that costs will be prohibitive and that more time is needed to develop the necessary skills in the industry to learn how to meet the standards. The question has to be asked: why resist a change that will help the industry to produce saleable products, services and, ultimately, homes in a difficult market?

The 27 houses at Easton Mews have been built to achieve an A3 BER at remarkably low costs

Besides, as has been argued in Construct Ireland before, the argument about higher standards increasing costs is essentially bogus. It’s well known amongst property economists that in a falling market, wise builders spend more on construction costs to make a sale. On top of this, there is no guarantee that the cost of meeting higher mandatory construction requirements results in house prices increasing. The market determines what it’s prepared to pay for property, after all. Therefore, if construction costs go up, land prices must fall to make room for this increase.

If arguments are made on the extra cost and difficulty for the construction industry of meeting higher energy performance levels, this surely pales in comparison when weighed against the cost and difficulty the home buyer would face both in terms of paying rising energy bills and in terms of carrying out the remedial energy efficiency upgrade to make living in the house viable in the years ahead, when fossil energy is at first more expensive, before becoming too scarce to use at all.

Of course, the extra construction costs of meeting the new 40% reduction in heating, hot water, cooling and lighting will invariably come down as economies of scale kick in and the industry learns which solutions are proving most cost-effective. To take one example familiar to readers of the last edition of Construct Ireland, the recently completed Easton Mews housing development managed to reach an A3 energy rating – and over a 50% energy reduction relative to building regulations – using conventional building materials, all at a cost of less than e100 per square foot.2 Not so long ago I had conversations with developers who laughed at the notion that this was possible, given that this cost is lower even than much standard development.

Though this project did not have the budget to include renewable energy heating, I’ve calculated based on real costings that, for a project like Easton Mews, it’s possible to comfortably exceed the renewable energy requirement set under the new Part L whilst bringing the total build cost up to less than e103 per square foot. Clearly, with a little ingenuity costs are not an issue.

Easton Mews is also notable in terms of the airtightness levels the homes have achieved, which were as low as 2.26m3/hr/m2 at 50 pascals pressure. To put this in context, the proposed air permeability rate under the new Part L is almost exactly four times this rate, at just 10m3/hr/m2 at 50 pascals. In this light, the proposed airtightness levels are, if anything, too low. Perhaps the Department of the Environment thought that, introducing more stringent requirements would impact negatively on ventilation rates given the fact that so many homes are still built with uncontrolled ventilation, such as by effectively punching holes in walls and slapping in a vent. Often the occupant finds the building so difficult to heat due to its draughty construction that they block up these vents. Their ventilation system is instead provided by opening windows and, alarmingly, through the leaky structure which is the cause of the problem in the first place. It’s therefore critical and long overdue that Part F of the Building Regulations is updated promptly to make well-designed ventilation mandatory, be it through passive or mechanical means, and preferably with heat recovery in either case.

In the interim, however, air permeability rates of at worst 7m3/hr/m2 at 50 pascals would be a comfortably achievable target. Hopefully submissions made during the consultation period will encourage the department to raise the standards when the new Part L is finalized. To put this in context, the UK government backed Energy Saving Trust stipulate that 5m3/hr/m2 at 50 pascals is a good practice level of air permability. Even at this reduced ventilation level, the Energy Saving Trust stresses that conventional ventilation – background ventilators such as trickle vents with local extract ventilation in wet rooms – is acceptable. Of course, whole house heat recovery ventilation would be a preferable option, and according to the Trust, is viable at 5m3/hr/m2. As should be expected, once air permeability is reduced to what the trust considers to be best practice – 3m3/hr/m2 – conventional ventilation becomes regarded by the trust as unsuitable, and designed ventilation systems, ideally with heat recovery, become essential. The point here is that Part L would not be running the risk of causing buildings to be under-ventilated if it increased air permeability to as high as the UK good practice level, and that a rate of even 7m3/m2 would have to be regarded as fairly conservative, but a very achievable and worthwhile improvement nonetheless.

Noel Dempsey, former Minister for Communications, Marine & Natural Resources peering through the tubes of a solar collector at the launch of the Greener Homes Scheme in March 2006

Although there are major question marks over the proposed air permeability rate, this aspect of the new Part L still represents a significant change, if only in terms of the fact that airtightness will finally be measured. The requirement for blower door pressure tests for new homes will bring a degree of transparency to the industry in terms of how effective different building forms are, how conscientious builders are, and how much attention building designers are giving in the design process to making airtight buildings easily achievable.

Within hours of the proposed changes to Part L being announced on September 21st, the Irish Home Builders Association was calling for the Department of the Environment to allow a longer lead in period before the new regulations are implemented. IHBA Director, Hubert Fitzpatrick, said that the new Part L was being introduced without a “realistic” transitional period.

“The new regulations affect the design, planning and construction phases of the development process”, he said. “The proposed timescale does not take cognisance of the technical challenges being imposed upon all facets of the construction industry, and is unrealistic as a result”.4 How much of a technical challenge can it be for the industry to put more insulation into walls, which will in itself would prove a very cost-effective means of getting much of the way towards compliance? And how difficult is it for designers, where possible, to place the emphasis on larger windows to the south, and smaller windows to the north?

I was interviewed along with Fitzpatrick later that day on Today FM’s the Last Word, where he went on to question the capacity of the renewable energy sector to meet the mandatory demand, which will typically equate to between 10 and 20 per cent of a building’s heat energy requirement. As I said in response, the 16,000 successful applications under the Greener Homes scheme since March 2007, along with developers building several thousand homes integrating renewables (whilst also achieving the 40 per cent energy reduction) under the House of Tomorrow programme, are testament to the renewable energy sector’s ability to meet a dramatic, even largely unpredicted demand.

It’s worth considering that when Greener Homes was alluded to in December 2005’s budget, the industry, which was comparatively small at the time, had less than four months to prepare before the scheme was launched. Additional pressure was placed on the industry by virtue of the fact that so many of its new customers were already living in their homes, and therefore wanted their renewable energy system installed immediately. The sector will be much better equipped to meet the demands of Part L, given that it will be able for the first time to plan ahead and make projections on likely demand. Notably, as Part L is not set to be introduced until July 2008, with the requirements only applying to all substantially completed new homes by July 2009, the renewable energy industry has almost two years to ramp up capacity to suitable levels.

Furthermore, as readers of Construct Ireland will be aware, developers on a rapidly growing number of very large projects are opting for up to 100% renewable energy-based district heating systems, with large, centralized energy sources piping heat to hundreds of homes and other buildings. District heating will invariably play a key role in helping to surpass these requirements, and will help to ensure that the renewable energy sector is not spread too thin, whilst also offering substantial cost benefits for developers, and removing maintenance requirements from occupants.

I spoke to Minister Gormley at the media launch of the new regulations in Kilternan, County Dublin, and asked what his views were on any concerns within the construction industry that the requirements might be set too high or coming in too soon.

Ministers Ryan and Gormley at the media launch of the new Draft Part L. The Launch was held at the Cowper Care nursing home and sheltered housing scheme, which has been calculated at an A3 energy rating, and surpasses the requirements of the proposed regulations

“Well I think it’s achievable, and certainly in my discussions with builders, they know that the department is now serious about this” he said. “Everyone now has to come on board. We’re working together, it is a partnership approach, but it’s also an approach which I think recognizes the urgency of the situation.

“We can no longer afford to be building inferior houses, and I’m putting that bluntly. What we have to do, it to get the standards up and what I’m saying to people is this – and they need to take me at my word – that this is only the beginning. 40% is the start, it goes to 60% [in 2010] and I’m deadly serious about going to zero carbon. I’ve seen houses now that have been built in the UK, I’ve had consultants in to the department, talking to my people about this. So the department is under no illusions that we’re going to zero carbon and I hope to go to zero carbon before 2016”.

The construction industry would do well to quickly purge itself of the business-as-usual, build cheap and sell high attitude which has played a key role in eventually undermining consumer confidence in buying homes. When the industry realises that the vision for Ireland laid out by Ministers Gormley and Ryan is in its own interest as well as those of Irish people, it can start the process of rebuilding a deeply fractured consumer confidence in buying homes, to the benefit of everyone.

For information on how to make a submission during the consultation period, which ends in December, visit www.environ.ie

1 http://www.lansingmortgages.com/pbf060105.htm

2 Stuart, J., “Out of the ordinary: Deceptively innovative A rated housing at standard costs”, Construct Ireland Issue 9 Volume 3

3 “Energy efficient ventilation in dwellings – a guide for specifiers”, the Energy Saving Trust

4 http://www.rte.ie/business/2007/0921/building.html

- Articles

- Energy Performance of Buildings Directive

- building regulations

- part l

- heat recovery

- Ventilation

Related items

-

Scotland to accept passive house as regs compliant

-

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house -

Embodied carbon & zero emission targets adopted in new EPBD

Embodied carbon & zero emission targets adopted in new EPBD -

EU votes through EPBD recast

-

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems -

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold -

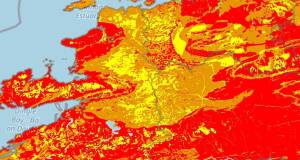

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal -

Disappointment at new building energy standards

-

ProAir retooling for the future

ProAir retooling for the future -

Ecological launch Inventer decentralised ventilation

Ecological launch Inventer decentralised ventilation -

Poor ventilation a Covid risk in 40 per cent of classrooms, study finds

Poor ventilation a Covid risk in 40 per cent of classrooms, study finds -

Efficient ventilation key to healthier indoor spaces – Partel

Efficient ventilation key to healthier indoor spaces – Partel