- Guides

- Posted

The PH+ guide to insulating foundations

While understanding wall and roof insulation is relatively straightforward, insulation under the ground floor can be a bit of a mystery by comparison. Not only is it buried in the ground, but there are notoriously tricky spots like the wall-floor junction that need to be detailed and insulated properly. And the design of your foundation often depends on site conditions and the type of structure you’re going to build, too. In this guide, we explain some different ways of insulating one of the most challenging parts of the building envelope.

The fabric-first based approaches required by tightening building regulations and best practice approaches like passive house are to a very large extent about ensuring high levels of unbroken insulation. That means the entire envelope – roof, walls, windows and ground floor. From hat, to jacket, to boots.

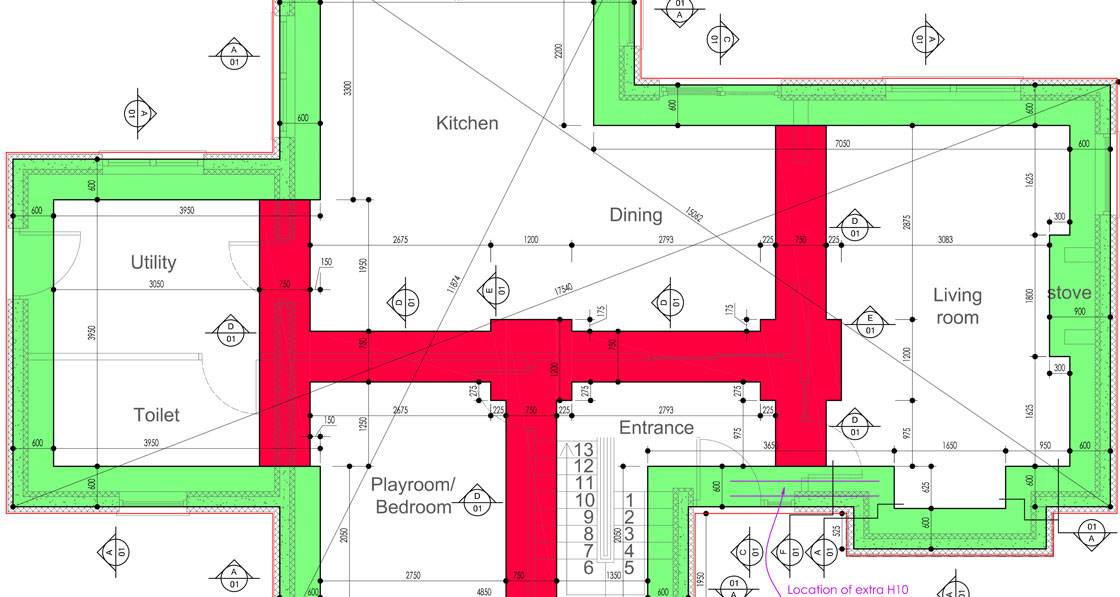

It goes without saying that one of the most important aspects to designing a passive house, or any high performance low energy building, is ensuring that whatever foundation system is used is well insulated and free of thermal bridges.

After all, the more you insulate the walls and floor of a house, the more heat that can escape from the thermal bridge at the wall-floor junction, increasing the risk of condensation and mould growth above the skirting. So insulating this junction becomes crucial.

1 pouring a concrete slab over Xtratherm insulation with an upstand of insulation around the edges; 2 An Isoquick passive slab foundation at the landmark passive-certified UEA Enterprise Centre; 3 aerial view of a KORE Insulation foundation system with two ring beams; 4 XPS insulation laid on the excavated ground floor of Ireland’s first certified passive house retrofit project, designed by PH+ columnist Simon McGuinness; 5 150mm Xtratherm insulation laid under the floor slab of Ireland’s first passive house pharmacy, on a tight site in Tipperary; 6 Geocell, a foam glass gravel material that is both load-bearing and insulating.

Unless you are constructing a high-rise or multi-storey building, choosing the most appropriate insulated foundation type for a typical project looks simple on paper, with most of the head-scratching reserved for the finer details of the job on site.

It’s unlikely that deep foundations will be needed unless the ground conditions are uneven or unusual in some respect. In most cases, the loads imposed by a typical low energy structure will be low relative to the bearing capacity of the surface soils, so the choice is generally between two types of shallow foundations systems.

Strip foundations are the more traditional and widely used in the UK and Ireland, where the walls are supported by a continuous ‘strip’ of foundation directly underneath the walls.

Raft foundations are basically reinforced concrete slabs of uniform thickness that cover the entire footprint (though not always) of a building. They spread the load imposed by a number of columns or walls over the foundation area. As the name implies, this type of foundation essentially ‘floats’ on the ground like a raft floats on water.

Most passive house buildings tend to use insulated raft-type foundations where the concrete slab is poured into a ‘bowl’ or ‘tub’ of insulation that surrounds it entirely, insulating it from direct contact with the ground. The edges of this ‘tub’ of insulation are usually continuous with the wall insulation, and the method is generally more amenable to ensuring the foundations are thermal bridge-free.

So far, it might seem like insulated raft foundations are a bit of a no-brainer for low-energy buildings. However, it’s rarely quite that straightforward.

alt=1 Kingspan’s Aeroground EPS-insulated foundation system cut for double ring-beams to support the inner and outer leaf of a cavity wall; 2 the Isoquick insulated foundation system on the passive-certified Lansdowne Drive, London.

This article was originally published in issue 26 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

The choice of foundation system, even on passive house projects, can often depend on external factors like ground conditions. Indeed, on sites containing shrinkable clays that can be subject to significant movement due to tree roots and other growths (a common enough issue), the traditional solution in these cases it to dig way down, using pile foundations.

That said, raft-type foundations are often chosen over strip ones where ground conditions are poor or settlement is likely, and can also have the edge in terms of speed and cost of construction because less excavation is usually required and less concrete used.

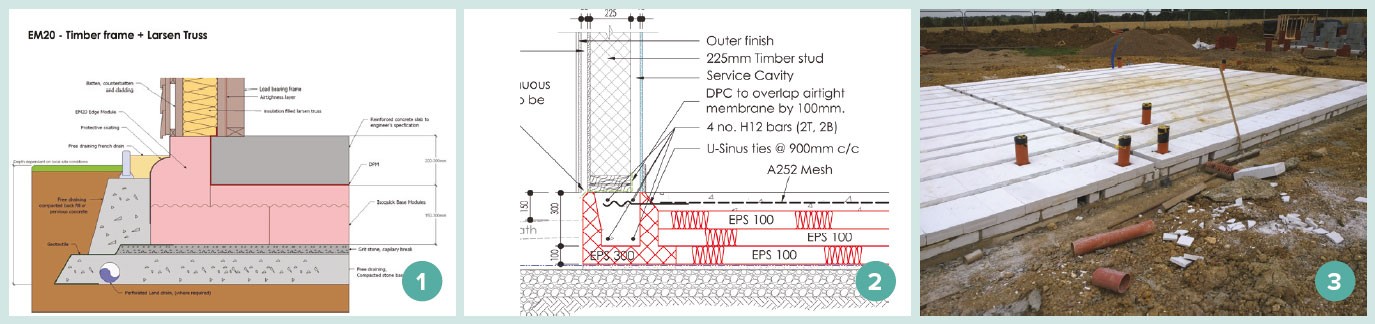

On the other hand, modern strip foundations and indeed other traditional types of foundation can also be brought up to standard in terms of radon barriers, proper insulation and thermal bridge-free design – indeed right up to passive house levels.

To take this point further, making a decision on a shallow foundation system based on the traditional understanding of how raft and strip foundations is to overlook the fact that some newer systems incorporate aspects of both raft and strip designs and seem to work well, while allowing for various build systems to be used — be it timber frame, ICF, cavity wall, externally insulated blockwork, etc.

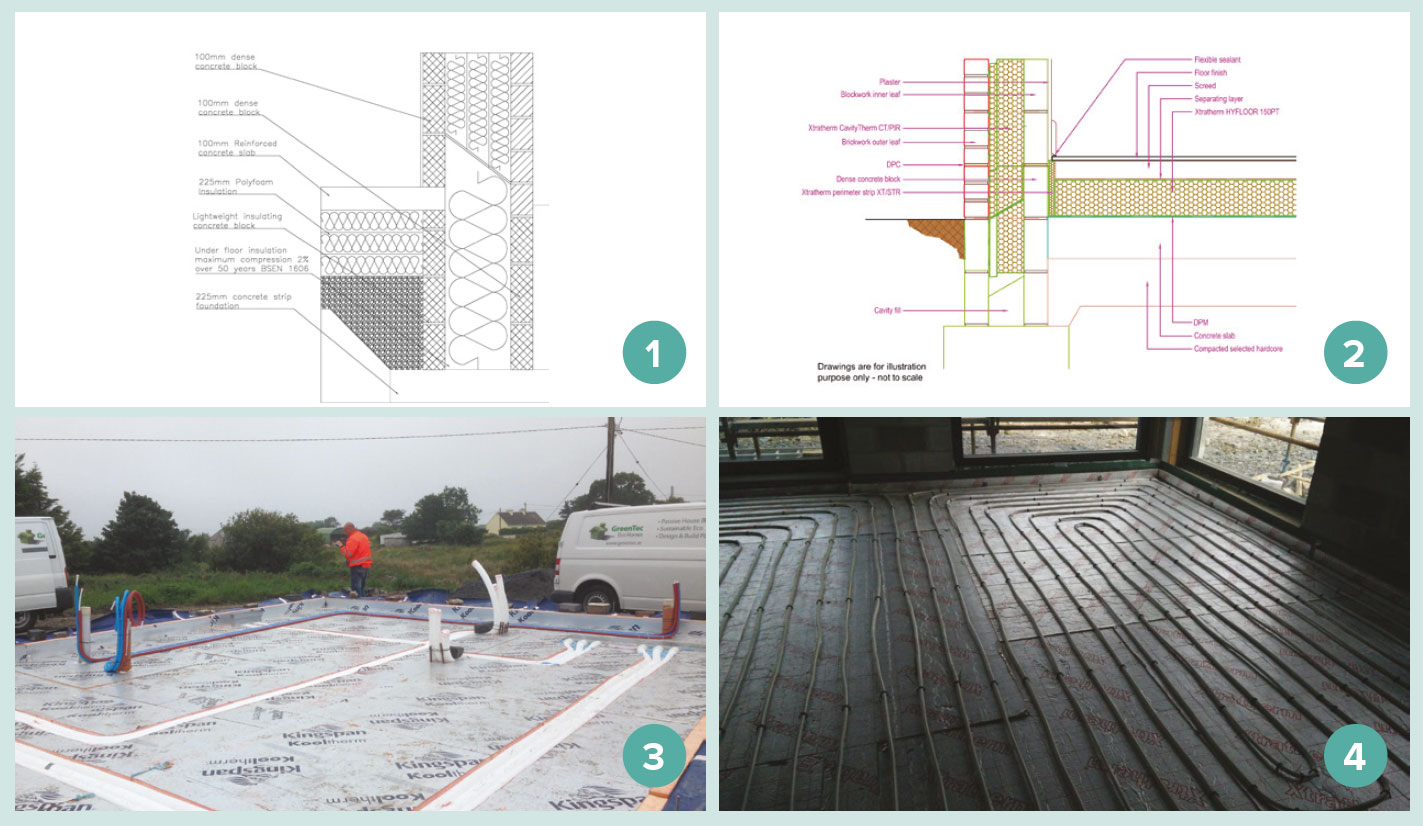

Installation of the Kore insulated foundation system showing: 1 preparatory groundworks; 2 laying of the EPS tub with underfloor heating pipes and; 3 the floor slab poured.

For instance, there are a few variations on insulated raft foundations, with some systems having a ‘ring beam’ or two where the concrete is reinforced around the edges, while others don’t. Indeed, some would argue that systems which incorporate ring beams are not really raft systems at all, particularly if the concrete slab isn’t thick enough to be considered a raft.

So it may be that raft versus strip distinctions aren’t really that relevant anymore when it comes to choosing how to insulate your home from what lies beneath.

Insulated foundation systems

Irish building materials giant Kingspan markets an insulated foundation system in Ireland called Aeroground, which is based on the Swedish Supergrund system (the company also offers a range of insulation solutions for conventional foundations). The load bearing walls and the floor slab of the building sit on top of an EPS layer, typically with trenches cut into the insulation near the perimeters for a ring beam of reinforced concrete to support the external walls, though the entire floor contributes to supporting the weight of the building.

According to Kingspan Insulation operations manager Joe Condon, the design of the system varies depending on the wall loadings. For instance, the version designed primarily for a timber or steel frame construction has both an inner and an outer ring beam — one for the frame, and one for an external leaf of block or brick — that are both thermally isolated from the floor slab.

“While it looks like a raft, it is not an actual raft as the ring beam supporting the walls is separate from the floor slab,” he said. But the ground preparations are essentially the same as those for a raft foundation, in that the site is stripped and made totally level with a uniform layer of stone over the entire footprint of the house.

Another key player in insulated foundations is Kore, which markets a passive house-suitable insulated foundation system called Kore Insulated Foundation. Technical sales manager Steven Magee is also keen to emphasise that the system in its standard form is not like a traditional raft foundation, but a system in itself.

“The issue is that because they look like a raft foundation, everyone calls them a raft foundation, but from a strictly engineering point of view they are not a raft foundation. They can be designed as a raft, but in their standard form they take elements of a traditional raft and elements of a strip footing foundation. It’s an insulated foundation system.”

1 Detail showing the Isoquick insulated foundation system under a timber frame wall; 2 drawing illustrating the floor-to-wall detail for Kingspan’s Aeroground insulated foundation system; 3 200mm of PIR insulation to provide insulation under the ground floor of a passive house scheme in Essex, which had an innovative approach to a traditional strip footing.

Like the Kingspan version, EPS 300, with its high compressive strength, is used in conjunction with concrete and steel, while EPS 100 is used in three layers for the floor insulation. Depending on the design, there can be one or two ring beams involved, for instance to carry an inner or outer leaf.

There are a number of other systems based on a similar principles, such as Viking House’s Passive Slab and Castleform’s Raft Therm. But another household name in insulated foundation systems is Isoquick, which has no qualms about describing its product as genuinely raft-based.

Jonathon Barnett of Isoquick insists that, structurally, a raft is very different to a ring beam with a connected floor slab. “The ring beam design carries all of the load down through the narrow strip around the perimeter, with a thin layer of concrete in between the beams. This concentrates the load on a narrow strip of insulation, limiting the amount of load that can be carried.”

He says that a ring beam design is essentially a strip footing with a reinforced beam, which by extension means the ground underneath the beam would have to be prepared to the same depth as a strip footing, although Kore and Kingspan say there is less need to excavate with their systems.

“Designing the slab as a flat raft means that the load from the walls is spread out, thereby enabling the foundations to be built where ground conditions are softer or more clayish,” said Barnett. “It also simplifies the reinforcement design, removing or greatly reducing the need for time consuming wired cages of reinforcement.”

A genuine raft design also works better thermally, too, he says, not least because the level of insulation under the edge of the slab remains consistent. Ring beam designs require the concrete slab to be thickened at the edges, meaning that the insulation has to be reduced compared to the middle of the building. “All of our details can be designed to achieve a passive standard at the ring beam,” said Magee.

Arguments about thermal performance aside, perhaps the choice among architects depends more on the versatility of all these systems in terms of accommodating the various different types of structure, but for others the appeal of a flat raft system may well be its inherent simplicity in terms of ensuring optimal thermal performance.

Another factor, of course, is cost. Insulated foundation systems may cost more materially, but one argument is that they require far less soil or ground excavation than traditional foundations, including the need to dig up trenches, which in turn speeds up construction and cuts down the risk of health and safety issues.

“Removing the muck is simple and straight forward without the trenches,” said Barnett. “Likewise the sub base and levelling stone take only a day or two to prepare. Once the stone is in place your site is out of the mud making life easier for everyone working on the job. From an empty site to a finished floor is usually less than two weeks. We win contracts simply on the muck away savings alone.”

Structural engineer Hilliard Tanner is also of the view that overall, the costs even out between insulated and non-insulated systems. “We have done a number of insulated foundations that work out cheaper overall than traditional strip foundations,” he said. Insulated foundation systems are certainly attracting more attention from bigger contractors, “because they work really well with modular housing as well and builders like the idea of reducing the skilled labour required on site”, says Steven Magee of Kore.

1 Foundation detail at Denby Dale, the UK’s first certified cavity wall passive house, with a lightweight insulating concrete block at the wall-to-floor junction; 2 Xtratherm detail showing upstand of insulation around the edge of the floor slab to minimise thermal bridging with the inner leaf of the cavity wall; 3 200mm Kingspan insulated strip foundation with 70mm upstand to edges under a passive house in Inverin, Co Galway; 4 this passive house in Co Meath has a strip foundation with 200mm Xtratherm under the concrete slab, which also encases the underfloor heating pipes, and Quinn Lite thermal block at the wall-to-floor junction.

There is also the reduction in concrete use with insulated foundations. “From a cost point of view, you use a lot more polystyrene than you would in a traditional foundation, but that is offset by using approximately 50pc less concrete,” Magee adds.

Furthermore, there is an element of pre-fabrication with such systems in that you are more likely to see the exact specifications of the foundation upfront, including the amount of insulation and concrete used. This can minimise the likelihood of mistakes and material wastage on site. “From a QS point of view, it allows them to work out exact quantities of materials that will be needed up front – as opposed to traditional strip foundations where you dig a trench and approximating the amount of concrete required to fill it.” As mentioned earlier, ground conditions remain the biggest factor, meaning that strip or pile foundations may be a better choice when the soil is softer or subject to potential disturbance from nearby tree roots, or if the wall loadings of a given structure are likely to be too heavy in parts, or if the site in question contains aquifers.

Magee says that Kore’s system can be used in almost any ground conditions. “If ground conditions are poor, the system can be designed more like a traditional raft, whereby ground beams and ribs within the slab are incorporated to make the entire system act monolithically. In the case of very poor ground conditions, e.g. on filled ground, the raft can bear onto standard piles, but whilst also maintaining a complete thermal break between the piles (ground) and the raft”. In any case the system needs to be designed by a suitably qualified engineer based on the ground conditions and superstructure.

Strip foundations

While a common refrain among raft foundation advocates is that strip foundations can lead to thermal compromise when compared to insulated foundation systems, Passive House Plus has featured plenty of projects over the years, of various construction types, that have achieved the passive house standard with a traditional strip foundation.

The key is good detailing. This can mean wall insulation that continues down below ground level, reaching down below the floor insulation, and ensuring a sufficient overlap of thermal insulation between the wall insulation and underfloor insulation. Given that ground temperatures below certain depths remain relatively warm compared to external conditions, the absence of insulation beneath the blockwork separating the wall insulation and floor insulation may be a non-issue – if the insulation layer is brought down below the floor insulation level. For instance, leading Irish insulation manufacturer Xtratherm recommend the wall insulation layer being brought down to a depth of 225mm below the floor insulation layer.

Foundation at an A1-rated social housing project by Linham Construction in Dublin, showing 1 Geocell foam glass gravel and aggregate under the concrete slab; 2 followed above by a radon barrier and; 3 225mm reinforced concrete with a power float finish.

Foundation at an A1-rated social housing project by Linham Construction in Dublin, showing 1 Geocell foam glass gravel and aggregate under the concrete slab; 2 followed above by a radon barrier and; 3 225mm reinforced concrete with a power float finish.

If there is insulation on the room side of the wall build-up — for example on the inside of a timber frame —thermal bridging at this junction can be minimalised by, for example, installing an upstand of insulation around the edges of the floor slab that join with the room-side insulation as per the ACDs (Acceptable Construction Details).

Equally, a common detail for masonry projects is to have a low thermal conductivity block at the base of the inner leaf of masonry, where the wall meets the underfloor insulation, to minimise heat loss through this junction. Xtratherm told Passive House Plus it had conducted an extensive thermal analysis of a wide range of products on the Irish market designed to effectively insulate floors and floor/wall junctions.

“Curiously, many of the system suppliers do not quote a resultant Psi value for this junction,” said Mark Magennis, senior technical adviser at Xtratherm. Magennis said that the resultant Psi values from well-detailed insulated strip footings are generally comparable to insulated foundation systems.

“Yes while there can be a reduction in the Psi value with some insulated foundation systems, traditional strip foundations detailing with the use of medium density blocks and careful detailing of conventional insulation also reduces the Psi value,” he said.

The company’s own detail is based on the Irish acceptable construction details (ACDs) and allows for typical compressive loadings for dwellings, and radon detailing in accordance with Irish EPA guidelines.

“It can also dispense with the requirement for bespoke engineering calculations as required with foundation systems,” Magennis said. The detail employs the company’s CavityTherm Foundation Riser boards in the cavity, extending below the damp proof course (DPC), ensuring at least 225mm overlap from the top of the floor insulation. It features a radon barrier dressed across the cavity, dissecting or weaving under the insulation and then extending under the floor insulation.

Magennis said that for anyone looking to decide on a foundation system, the key thing is that the performance of products and system is clearly defined, and performance claims are published and certified by a suitably qualified person – such as an NSAI-registered thermal bridging modelling assessor – in a way that is easy to understand. He also emphasised the need for “better and easier detailing on site”.

Another alternative to insulated raft or strip foundations is Geocell, a foam glass gravel material that works as a lightweight exterior insulation and sits below the floor slab. It is load-bearing, with a comparable compressive strength to a hard-core, and free-draining. The system is passive house certified and offers similar thermal performance to mainstream insulation systems, with a lambda value of 0.08 W/m2K. It is made entirely from recycled glass, and distributed in Ireland by Linham Construction.

Retrofit

Of course it’s probably no surprise to learn that, short of lifting up the entire building, it’s practically impossible to retrofit insulated foundation systems.

But there are some measures that can be reasonably cost-effective to implement, such as digging out the ground floor and adding insulation. “What you’d be doing there is to dig out the floor down to a level that would be compact enough to create a level base, put in your insulation and put down a floor slab and put a slip of insulation around the perimeter to create a cold bridge divider between the floor slab and the lower part of the inside wall,” said Joe Condon of Kingspan.

The biggest issue would be waterproofing and keeping the load-bearing structures in place while you rip up the floor.

Another step might be to bring external insulation down below ground floor level to address thermal bridging. Sometimes, just bringing external insulation deep enough down underground will be sufficient as, once you get below certain depths, ground temperatures pick up anyway.

Radon barriers

In areas that have been listed as having high radon levels, Irish and UK building regulations generally stipulate that new buildings should be fitted with a strong radon barrier and sump, while areas less affected may still need some basic protective measures.

According to Hilliard Tanner, with insulated foundation systems as he details them, the radon sump goes into the top of the fill as normal, and then barriers are placed under the insulation, and leaving it out past the sides of the insulation. Alternatively, you could run the barrier on top of the first or second (of the three) layers of floor insulation, then in contact with the ring beam.

-

Foundation at an A1-rated social housing project by Linham Construction in Dublin, showing Geocell foam glass gravel and aggregate under the concrete slab

Foundation at an A1-rated social housing project by Linham Construction in Dublin, showing Geocell foam glass gravel and aggregate under the concrete slab

Foundation at an A1-rated social housing project by Linham Construction in Dublin, showing Geocell foam glass gravel and aggregate under the concrete slab

Foundation at an A1-rated social housing project by Linham Construction in Dublin, showing Geocell foam glass gravel and aggregate under the concrete slab

-

-

-

Radon barrier

Radon barrier

Radon barrier

Radon barrier

-

Pouring a concrete slab over Xtratherm insulation with an upstand of insulation around the edges

Pouring a concrete slab over Xtratherm insulation with an upstand of insulation around the edges

Pouring a concrete slab over Xtratherm insulation with an upstand of insulation around the edges

Pouring a concrete slab over Xtratherm insulation with an upstand of insulation around the edges

-

The floor slab poured

The floor slab poured

The floor slab poured

The floor slab poured

-

225mm reinforced concrete with a power float finish.

225mm reinforced concrete with a power float finish.

225mm reinforced concrete with a power float finish.

225mm reinforced concrete with a power float finish.

-

An Isoquick passive slab foundation at the landmark passive-certified UEA Enterprise Centre

An Isoquick passive slab foundation at the landmark passive-certified UEA Enterprise Centre

An Isoquick passive slab foundation at the landmark passive-certified UEA Enterprise Centre

An Isoquick passive slab foundation at the landmark passive-certified UEA Enterprise Centre

-

Foundation detail at Denby Dale, the UK’s first certified cavity wall passive house, with a lightweight insulating concrete block at the wall-to-floor junction

Foundation detail at Denby Dale, the UK’s first certified cavity wall passive house, with a lightweight insulating concrete block at the wall-to-floor junction

Foundation detail at Denby Dale, the UK’s first certified cavity wall passive house, with a lightweight insulating concrete block at the wall-to-floor junction

Foundation detail at Denby Dale, the UK’s first certified cavity wall passive house, with a lightweight insulating concrete block at the wall-to-floor junction

-

Detail showing the Isoquick insulated foundation system under a timber frame wall

Detail showing the Isoquick insulated foundation system under a timber frame wall

Detail showing the Isoquick insulated foundation system under a timber frame wall

Detail showing the Isoquick insulated foundation system under a timber frame wall

-

Aerial view of a KORE Insulation foundation system with two ring beams

Aerial view of a KORE Insulation foundation system with two ring beams

Aerial view of a KORE Insulation foundation system with two ring beams

Aerial view of a KORE Insulation foundation system with two ring beams

-

00mm Kingspan insulated strip foundation with 70mm upstand to edges under a passive house in Inverin, Co Galway

00mm Kingspan insulated strip foundation with 70mm upstand to edges under a passive house in Inverin, Co Galway

00mm Kingspan insulated strip foundation with 70mm upstand to edges under a passive house in Inverin, Co Galway

00mm Kingspan insulated strip foundation with 70mm upstand to edges under a passive house in Inverin, Co Galway

-

Isoquick insulated foundation system on the passive-certified Lansdowne Drive, London.

Isoquick insulated foundation system on the passive-certified Lansdowne Drive, London.

Isoquick insulated foundation system on the passive-certified Lansdowne Drive, London.

Isoquick insulated foundation system on the passive-certified Lansdowne Drive, London.

-

This passive house in Co Meath has a strip foundation with 200mm Xtratherm under the concrete slab, which also encases the underfloor heating pipes, and Quinn Lite thermal block at the wall-to-floor junction.

This passive house in Co Meath has a strip foundation with 200mm Xtratherm under the concrete slab, which also encases the underfloor heating pipes, and Quinn Lite thermal block at the wall-to-floor junction.

This passive house in Co Meath has a strip foundation with 200mm Xtratherm under the concrete slab, which also encases the underfloor heating pipes, and Quinn Lite thermal block at the wall-to-floor junction.

This passive house in Co Meath has a strip foundation with 200mm Xtratherm under the concrete slab, which also encases the underfloor heating pipes, and Quinn Lite thermal block at the wall-to-floor junction.

-

150mm Xtratherm insulation laid under the floor slab of Ireland’s first passive house pharmacy, on a tight site in Tipperary

150mm Xtratherm insulation laid under the floor slab of Ireland’s first passive house pharmacy, on a tight site in Tipperary

150mm Xtratherm insulation laid under the floor slab of Ireland’s first passive house pharmacy, on a tight site in Tipperary

150mm Xtratherm insulation laid under the floor slab of Ireland’s first passive house pharmacy, on a tight site in Tipperary

-

Geocell, a foam glass gravel material that is both load-bearing and insulating

Geocell, a foam glass gravel material that is both load-bearing and insulating

Geocell, a foam glass gravel material that is both load-bearing and insulating

Geocell, a foam glass gravel material that is both load-bearing and insulating

-

200mm of PIR insulation to provide insulation under the ground floor of a passive house scheme in Essex, which had an innovative approach to a traditional strip footing

200mm of PIR insulation to provide insulation under the ground floor of a passive house scheme in Essex, which had an innovative approach to a traditional strip footing

200mm of PIR insulation to provide insulation under the ground floor of a passive house scheme in Essex, which had an innovative approach to a traditional strip footing

200mm of PIR insulation to provide insulation under the ground floor of a passive house scheme in Essex, which had an innovative approach to a traditional strip footing

-

Xtratherm detail showing upstand of insulation around the edge of the floor slab to minimise thermal bridging with the inner leaf of the cavity wall

Xtratherm detail showing upstand of insulation around the edge of the floor slab to minimise thermal bridging with the inner leaf of the cavity wall

Xtratherm detail showing upstand of insulation around the edge of the floor slab to minimise thermal bridging with the inner leaf of the cavity wall

Xtratherm detail showing upstand of insulation around the edge of the floor slab to minimise thermal bridging with the inner leaf of the cavity wall

-

Kingspan’s Aeroground EPS-insulated foundation system cut for double ring-beams to support the inner and outer leaf of a cavity wall;

Kingspan’s Aeroground EPS-insulated foundation system cut for double ring-beams to support the inner and outer leaf of a cavity wall;

Kingspan’s Aeroground EPS-insulated foundation system cut for double ring-beams to support the inner and outer leaf of a cavity wall;

Kingspan’s Aeroground EPS-insulated foundation system cut for double ring-beams to support the inner and outer leaf of a cavity wall;

-

XPS insulation laid on the excavated ground floor of Ireland’s first certified passive house retrofit project, designed by PH+ columnist Simon McGuinness

XPS insulation laid on the excavated ground floor of Ireland’s first certified passive house retrofit project, designed by PH+ columnist Simon McGuinness

XPS insulation laid on the excavated ground floor of Ireland’s first certified passive house retrofit project, designed by PH+ columnist Simon McGuinness

XPS insulation laid on the excavated ground floor of Ireland’s first certified passive house retrofit project, designed by PH+ columnist Simon McGuinness

https://passivehouseplus.co.uk/magazine/guides/the-ph-guide-to-insulating-foundations#sigProId609cd85f7e