- Policy

- Posted

Incentive innovation

Energy Minister Eamon Ryan recently announced a e9 million fund to be administered by SEI for sustainable housing including, crucially, micro-generation of renewable electricity. Jason Walsh talked to SEI and industry figures to examine the scheme’s future.

The latest green fiscal measure from the government is to embolden Ireland’s renewable energy strategy by directly tackling both energy consumption and production at the coal face of carbon emission: housing.

The e9 million Low Carbon Homes Programme (LCHP) will be administered by Sustainable Energy Ireland (SEI) and will provide grants of up to 40 per cent of eligible expenditure to encourage developments of new homes to an energy performance standard exceeding the recently adopted building regulations.

Homes built under the programme will be at least 75 per cent more energy efficient and produce at least 70 per cent less carbon dioxide than homes built to 2005 standards and will have a minimum Building Energy Rating (BER) of A2.

Dwellings build to the standard of the recently adopted building regulations, would typically have a BER of B1, two grades below the minimum standard of the new programme.

As previously reported at ConstructIreland.ie, the scheme was announced by Green Party Minister for Communications, Energy and Natural Resources, Eamon Ryan TD, and will run until at least 2011. The new scheme will seek to achieve very low carbon emissions from supported homes by reducing energy demand and requiring a significant element of micro generation of renewable electricity.

“The plan is to build on the work of the House of Tomorrow programme,” said Sustainable Energy Ireland’s Ivan Sproule. “It dates back to 2001 when it was identified that there was a need to move forward in terms of the energy specification of Irish housing.

“After a slow start in 2001 and 2002, the House of Tomorrow programme took-off. The initial target was three thousand dwellings and we ended-up supporting almost six thousand.”

According to Sproule the Low Carbon Homes Programme was devised to help prepare the construction industry for the logical conclusion of increasing environmental standards – the requirement that all new homes be nett carbon neutral: “Minister Gormley wants a zero carbon target by 2013 – we’re using this programme to move the industry forward to the next level,” he said.

“What we’re trying to do is to bring deliverable solutions to the market – increased innovation, particularly looking at micro-generation as electricity generation will become more important.”

Principally targeted at schemes of five to fifteen houses, a figure arrived at by looking at current development market and planning trends, developers will be able to cover up to 40 per cent of additional construction costs associated with meeting the programme’s requirements up to a maximum grant of e15,000 per residential unit.

Developers may also apply for funding for ‘show house’ constructions, and individuals may apply for single houses where SEI deems they hold sufficient potential as a demonstration project, with the possibility of widespread replication and policy influence. In return for this, the housing must meet stringent energy consumption targets and, importantly, generate electricity on-site from renewable sources.

“The main technical requirements are for an A2 or better BER rating,” said Sproule. “In energy terms that means 50 kWh/m2/yr, or less, for heating, hot water and lighting needs.

“The next criteria are a 0.25 energy performance co-efficient and a 0.3 carbon performance co-efficient.”

An energy performance co-efficient of 0.25 means that every dwelling must achieve a 75 per cent reduction in energy use relative to Part L of the 2005 building regulations. Similarly, a carbon performance co-efficient of 0.3 demands a reduction of 70 per cent in carbon emissions.

Sproule continued: “The third thing is we would like to see micro-generation come into play. Minister Ryan has [already] announced a micro-generation programme and a complementary smart metering programme.”

Minister Ryan announcing the LCHP

SEI’s Low Carbon Home Programme calls for 10kWh/m2/yr of primary energy equivalent to be generated. This equates to a demand for the on-site generation of 4kWh/m2/yr.

Sproule said that on-site generation was crucial: “We will not accept projects where developers simply purchase ‘green’ electricity from a supplier,” noting that subsequent residents could then easily switch back to a non-renewable source.

Additionally, Sproule sees supplying electricity to the grid as a potential outcome of the programme: “Ideally you’d try and offset the electricity used on-site and then spill the rest into the grid,” he said.

Despite assurances from ministers and former Taoiseach, Bertie Ahern, at present it is not practically possible for micro-generators to sell electricity to the grid. Asked about this by Construct Ireland, Sproule admitted it was a source of frustration for some people but that the Government has already stated that things are set to change:

“Non-payment for [supplying] grid electricity is currently a major bone of contention. A smart metering pilot is underway and it’s expected that the outcome of this will see the introduction of time of use tariffs for consumption and possibly a feed in tariff for micro generation.”

In the meantime, SEI’s Low Carbon Homes Programme has found another way to make micro-generation attractive to developers and homeowners.

Development heaven

For developers, the Low Carbon Homes Programme offers a leg-up to the next rung on the green housing ladder. One example of the kind of development that the Low Carbon Homes Programme could encourage is Watermint, a sustainable apartment complex in Cabinteely, south County Dublin.

“We have an A2-A1 rating – we achieved a 76 per cent reduction in energy consumption,” said Neil Monahan, managing director of Watermint’s developer Monti.

Monti has worked hard to get the development as far ahead of today’s standards as possible: “When you put the figures into DEAP it tells you that our development is actually carbon negative due to the amount of photovoltaic panels we’re using.” Monahan notes that this figure excludes appliances and that a worst case scenario of a resident using every possible appliance would still result in a 60 per cent reduction in carbon emissions.

“We’ve done our statistics,” he said. “Some of the apartments are A2-rated, some are A1.”

Planning for the development started in 2005: “We wanted to push the envelope and make a real statement about sustainability. It’s a prototype for us [and] we’ve thrown the kitchen sink at it – biomass, heat-recovery ventilation, photovoltaics and more.”

Monahan, who is currently looking toward a possible future development in conjunction with sustainability consultant Jay Stuart of DW EcoCo in Palmerstown says the point is to stay ahead of the regulations: “At the moment we’re beyond the 2010 [Part L] standard. Palmerstown should be ahead of the 2012–2013 standard. We want to be ahead of the curve.”

According to Monahan, the Low Carbon Housing Programme’s key benefit is meaningful promotion of micro-generation through a clear financial incentive: “The only incentive for micro-generation at the moment is the chance of getting an A1 rating. This scheme will change that.”

Watermint is not the only development currently aspiring towards an A1 rating, however. Building contractors Inch Environmental Construction has two such schemes currently on its books – ground has been broken on a 102 apartment development in Montgomery Street, Carlow town whilst a 15 house development in Callan, County Kilkenny is nearing completion.

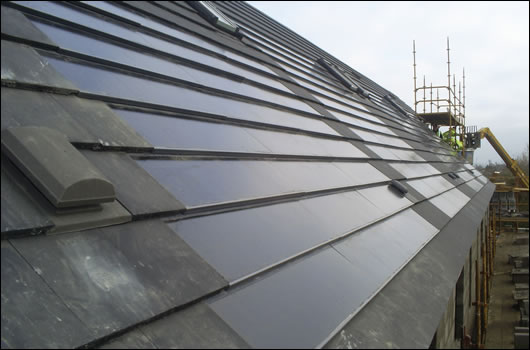

The Carlow development will feature ten roof-mounted five kW Proven wind turbines, whilst Solarcentury photovoltaic roof tiles were selected for the Callan scheme. The Timber Frame Company of Wexford has developed a highly insulated timber frame system with Inch, specifically with A1 in mind. Borehole based geothermal heat pumps are to be used in both developments to provide hot water and space heating, which will be supplemented with heat recovery ventilation systems – Proair heat recovery systems have already been specified at Callan along with Nibe 1240 heat pumps with a 90 metre bore hole and Unipipe underfloor heating.

Sustainability consultant Jay Stuart of DW EcoCo

Gary FitzPatrick, general manager of Inch Environmental Construction concedes that cost has been an issue with the two projects: “The difficulty in the beginning was trying to find cost effective products to help us to achieve A1” he said. “To an extent we’ve combated this by identifying products ourselves that weren’t represented on the Irish market, including everything from low cost triple-glazed window systems to solar lighting”.

New again

In order for developers, architects and specifiers to achieve the standards demanded of them by SEI, Ireland’s micro-generation industry will have to shift up a gear. It appears that this is exactly what is happening: “We will be looking at the project from the wind and photovoltaic point of view,” said Brian Ash of Cell Energy Ireland.

“We’re [particularly interested in] looking at distributed generation. We’ve had numerous inquiries for projects of around thirty homes covered by one 80 kilowatt turbine. In such cases it will supply the baseload.”

Ash explained that this kind of wind turbine is more efficient than typical micro-generation units: “It’s like the difference between micro-generation and commercial generation.

“Commercial generation has been around for at least twenty years, it’s not in its infancy.”

Cell Energy Ireland, an associate installer for leading PV company Solarcentury, has recently started exclusively supplying a range of larger turbines from the Netherlands-based WES. “We’re the exclusive Irish distributor of their three-phase turbines. We have a range up to 250 kilowatts – again, it’s a commercial generation product.”

Overall, Ash is enthused by the programme: “We’re very glad to see micro-generation getting a look-in. It’s about time,” he said, pointing out that micro-generation will only help Ireland as a nation: “Ireland’s 2020 carbon targets will cost us [dearly] if we don’t make them. We need to start making inroads as soon as possible.”

He also points out that the scheme will bring the Twenty-Six Counties closer into line with the North: “There they have feed-in tariffs, grants in place and Renewable Obligation Certificates (ROCs).”

Renewable Obligation Certificates mean that for every unit of electricity generated from renewable sources offset payments are made: “You get four pence as a carbon credit for every unit generated.” As this payment is on top of the feed-in tariff it’s quite an incentive to get involved in micro-generation.

”The technology is already there,” said Ash, “you can see why ESB hasn’t made major moves toward it – it will reduce their profits [but] this technology will not take-off without feed-in tariffs. France, Germany, Spain, the UK – even in America they’ve got it.”

So, while we wait to see when – and indeed if – ESB will allow feed-in as the government has said it will the grant aid will certainly get contractors and developers involved in micro-generation.

“e15,000 would put in a 2.5 kilowatt turbine or a small photovoltaic system – something around 1.5 kilowatts. It’s a reasonable start in comparison to other countries – the UK, for example, has just reduced its grants to £2,500 (approx. e3,172) – so, in combination with smart metering it’s a good start”.

Although happy to see the grant-aid, Ash argues that it is in fact of secondary importance compared to the feed-in tariff – something, it should be noted, beyond SEI’s control.

“A good feed-in tariff will be better than grants. Germany, for example, has no grant but pays 48c per unit of electricity,” he said.

In Germany the feed in tariff structure started with rates as high as 58c with the government informing the public that the tariff would reduce over time for new applicants –therefore encouraging quick take-up – but people who signed up early were guaranteed the higher rate over up to two decades. This was supported with low or zero interest loans. France has recently followed suit with a feed in tariff of up to 57c - a remarkable figure given the country’s heavily subsidised low electricity costs.

Of course, this figure is well above the market value of around 16c per unit but Ash explains that it encourages significant carbon reductions by spreading the cost: “The people who don’t generate pay for the people who do, by paying slightly more per unit consumed – around 18c.

Solarcentury PV tiles at Inch Environmental Construction’s Callan development

“Feed-in in England and Wales, meanwhile, is 4.5 pence (approx. 6c) plus the ROC, which amounts to around eight pence per unit (approx. 10c). In Scotland the feed-in is eighteen pence (approx. 23c) plus the ROC.”

Ash says that instigating a feed-in tariff in Ireland would not be a complicated task: “A basic import-export metre is all that’s required, not necessarily smart metering. ESB has the units on the shelf but they’re delaying on the basis of the [need to introduce] smart metering.”

For all of Ash’s enthusiasm for wind power, some have raised doubts about whether wind power will really be effective enough to gain support under the scheme. Although SEI has not ruled-out any form of energy generation, some have noted that photovoltaic solar will prove to be the path of least resistance.

Leading sustainability consultant Jay Stuart, who has worked on the redevelopment of the Fatima Mansions in Dublin as well as Clonburris Strategic Development Zone and decentralisation programmes for both the Department of the Environment, Heritage and Local Government and the Department of Defence, feels that despite SEI’s openness the scheme will necessarily favour photovoltaic panels.

“The Low Carbon Housing Programme is undoubtedly a good thing,” said Stuart. “It’s the next logical step. They want to promote micro-generation and are doing it with this, effectively, upgraded ‘House of Tomorrow’ scheme. They want to stimulate the industry.”

Stuart’s confidence is based on SEI’s track record: “What SEI has done in the past has been successful,” he says, “[but] I think the only technology that’s going to work is photovoltaic panels.”

He explains that, in his view, wind turbines will run into significant difficulties, noting that small, domestic turbines often generate tiny amounts of electricity but larger turbines will have their own problems: “There are planning issues with large scale wind turbines. Typically you don’t build within 500 metres of a large scale wind turbine.

“There is a huge potential problem [with some developers] – and this is almost one of my hobby horses – with wind turbines being used to wave a green flag rather than actually make a real contribution to renewable electricity generation.”

Stuart’s primary issue with wind turbines is that of turbulence: “Buildings and wind turbines don’t go together. The two are usually mutually exclusive. A recent report1 in the UK showed that the actual output of wind generators is usually less than half of the claimed figure.” The report, by the Carbon Trust, placed particular emphasis on the poor performance of urban micro turbines, and stressed the critical issue of selecting location based on taking measurements of wind levels, in order to make the technology stack up.

Stuart also pours water on the idea that combined heat and power (CHP) systems might be accepted under the rubric of renewable generation: “We have independently asked SEI about bio-oil and their problem is it would be too easy to switch back to oil.”

He also notes that woodchip-based CHP would be an ungainly solution: “It would be extremely expensive. Also, I don’t think anybody makes a small enough system anyway,” he said.

“There is a miniature CHP engine called DACHS. It’s a 600cc three or four kilowatt system. It’s fine for a fair-sized house. It costs e20,000 and if you run it on bio-oil it would be viable.”

Stuart fully understands the reason, however, that CHP may not be viable and does agree that it could be the source of a potential problem: “I do agree with their view; I take SEI’s point. If they could devise some way of proving a system was running on bio-oil it would be great, but how?”

Peter Keavney of Galway Energy Agency takes a third view on the issue: “We’ve got the details of the programme but we haven’t had a detailed look at it yet, and there is a tandem call for proposals from the Department of the Environment on social housing. It’s [effectively] the revised House of Tomorrow.

“Generation should be assessed on a case-by-case basis,” he said. “Wind may in fact be applicable in some urban situations where you have large gardens, for example.

“The application of generation types needs to be designed and assessed according to the site,” he said.

Keavney also points out that one-off rural houses are not an insubstantial proportion of Irish new-build housing: “The only thing in the construction industry that is thriving is one-off houses in the countryside,” he said. In fact, figures indicate that individual dwellings in rural areas account for up to 40 per cent of newly built housing in the state.

Keavney, like others, is at pains to point out that, whatever form the generation takes, metering is of paramount importance: “We should be leveraging [the Low Carbon Homes Programme] in relation to smart metering. Electricity is still our ‘dirtiest’ fuel so there will be a requirement for smart metering to be deployed.”

Choosing power

For SEI particular technologies are not the real focus of the programme. Instead, the point is to change how developers and homeowners think about electricity and to make the concept of micro-generation a viable one in practice.

“It’s about getting solutions that can be delivered to the market,” said SEI’s Ivan Sproule.

Sproule also notes that while innovation is key, there will be no artificial restrictions placed on developers: “We’ll be looking at a geographical spread and a variation of housing types. We can’t just discount a builder in one part of the country because he’s doing something that someone’s already done elsewhere.”

He also says that developments of more that fifteen houses will be considered: “If someone has an exceptional scheme we’ll certainly look at it.”

On both points he says that the key is wise use of funds: “It is taxpayers’ money – we have to be mindful of that.”

Ultimately, despite some questions over how the scheme will roll-out and which technologies will turn out to be viable, the Low Carbon Homes Programme has been welcomed by the industry – little wonder given the sensitivity of the construction industry at the moment. At a time of downturn when the temptation may have been to relax restrictions in order to stimulate growth SEI’s Low Carbon Homes Programme will instead help Ireland to step up to the plate and develop more sustainable house than it has ever seen before, laying the groundwork for a future when grant aid will be unnecessary.

As Sproule says: “It’s trying to activate the market and increase the capacity of the builder-developer.”

1 The Carbon Trust “Small-scale wind energy: Policy insights and practical guidance”, August 2008

- Articles

- policy

- Incentive innovation

- A2 Housing

- Low Carbon Homes Programme

- sei

- Building Energy Rating

- house of tomorrow

Related items

-

Ireland joins whole life carbon data initiative

-

WorldGBC launches green building policy principles for governments

-

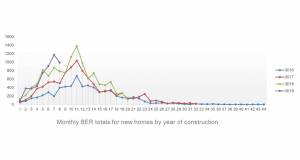

BER data indicates national house building growth – except for Dublin

BER data indicates national house building growth – except for Dublin -

Cuckoos & magpies: state house-buying hits record

Cuckoos & magpies: state house-buying hits record -

Blind & shutter group calls for Part B changes

Blind & shutter group calls for Part B changes -

Wales votes to cut emissions 80%

Wales votes to cut emissions 80% -

Low carbon homes forum to tour the UK in 2019

Low carbon homes forum to tour the UK in 2019 -

Filling the retrofit policy void

Filling the retrofit policy void -

Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink

Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink -

Policy for zero, or zero policy?

Policy for zero, or zero policy? -

Analysis: 12,000+ homes built in 2017 – as energy standards marginally fall

Analysis: 12,000+ homes built in 2017 – as energy standards marginally fall -

Why construction contracts must change in light of Grenfell

Why construction contracts must change in light of Grenfell