- Ventilation

- Posted

Clearing the air

Ireland has paradoxically embraced what could be regarded as the two extremes of ventilation. On the one hand, the average Irish home is ventilated by ill-considered holes in the wall or trickle vents, both of which are often blocked up by occupants experiencing discomfort in cases of over-ventilation. This effectively means the occupant is reliant on drafts resulting from the leaky construction for ventilation – with a high risk of creating unhealthy conditions. On the other hand those homes that do install a ventilation system are increasingly tending to go for what’s regarded to be at the top-end of the range, a mechanical system with heat recovery. But there’s a wide array of other options out there, including a system that’s fairly common in Europe but practically unheard of in Ireland – demand controlled ventilation.

More likely than not, your windows, doors and even electricity sockets are allowing unwanted air to come into your home, causing you to crank up the heat in the winter. So-called ‘leaky’ homes are the rule rather than the exception in Ireland, yet truly energy efficient homes require the building structure to be air-tight and perfectly sealed away from the elements.

A humidity-sensitive extract unit with presence detection next to a monitoring device measuring co2, humidity and temperature. The monitoring device was manufactured by Aereco for the Paris monitoring study

In this eco-home context, purposefully making use of a hole in the wall to ventilate the house doesn't really make sense as it basically allows for large amounts of air to circulate in the dwelling uncontrolled. That’s not to say there aren’t huge benefits in going down the hole in the wall route, if it’s done in a controlled manner as can be the case with passive stack and mechanical extract ventilation. In and of itself, passive stack doesn't cost much and can work very well but needs to be properly designed.1

In practical terms, the whole point of installing a ventilation system in your home is to maximise your building’s indoor air quality – that is, to make sure you live in a healthy environment. If you can save some energy in the process, that’s a definite bonus, but it’s not really the point. The point is, you don’t want your air-tight home to turn into a petri dish for bacteria.

A humidity-sensitive air inlet with acoustic attenuation placed here on a roller shutter, also as part of the monitoring study

1 Demand controlled ventilation can be used in conjunction with passive stack ventilation but it’s not as well established as DCV coupled with standard mechanical ventilation. This option only suits certain types of dwellings (location and height are very important factors) and much attention must be given to both design and installation.

If your home is sufficiently insulated and sealed up at the seams then HRV can help you to heavily reduce your heating needs – to the point that you can remove the requirement for a heating system if you’re building to the Passivhaus standard. It is often argued that HRV is pretty much the only way of making a passive house work – it’s a mandatory part of the Passivhaus standard – but it’s also suitable to homes that aren’t completely air-tight. It all depends on the building’s specific characteristics. In the case of a retrofit this will often have to do with whether or not there’s room to install the ducting without paying through the nose for it.

HRV basically reuses the heat generated by the air that is discarded from the wet rooms in order to pre-heat the fresh (ventilation) air coming from outside. This in turn reduces your heating requirement as the cold outdoor air barely needs any heating or in the case of typical Irish winters, none at all. This is especially useful in the case of cold winters – the notion being that the higher the temperature difference between indoors and outdoors the more you'll get out of your heat recovery system. In this sense it's little surprise that such ventilation systems have proven especially popular in countries like Sweden or Denmark.

David McHugh of ProAir Systems demonstrates the ease of access to the heat exchanger for cleaning. McHugh says that heat recovery ventilation is particularly well suited for dealing with the dampness that characterises Irish weather

In Ireland, typical winters are indeed more damp than cold, which might suggest that DCV is best suited for our climate. But HRV supporters say that heat recovery ventilation is particularly well suited to dealing with the dampness that characterises Irish weather. David McHugh of heat recovery ventilation manufacturer ProAir argues that on the continent, where the ambient humidity is much lower, HRV can cause the air in the house to become too dry. “Here in Ireland we can have the opposite problem, where inadequate ventilation results in condensation occurring, especially on colder surfaces,” he says. When air is taken in from outside and warmed in the HRV system to approximately 18°C the relative humidity is dropped to around 30 per cent, from an Irish average of over 80 per cent. This allows the air to pick up excess moisture as it makes its journey through the building to the extract points. As this wetter air is now exhausted to outside through the system it is cooled (by the incoming air) and drops out water, which is drained away.

According to McHugh there is energy in this condensate which can be recovered. “Most people don’t realise that the heat they consume is used not just to raise the temperature in the premises, but also to absorb any moisture created,” he says. “This component of the total heat is called latent heat and it is not normally possible to recover it and reuse it effectively without raising the indoor relative humidity. If you don’t recover this latent energy you have to get rid of it or else it will result in condensation.” He says his company is collaborating with a Dutch company in an R&D project to usefully recover the latent energy from the condensate.

Maintenance is probably HRV’s weakest point, as the filters need regular replacement. However if the system is bespoke (properly designed to the dwelling’s requirements) then the replacement shouldn’t need to take place more than once or twice a year, depending on location and use. Replacing the filters, however, is not a difficult endeavour and can easily be done by the homeowner. The important thing to bear in mind is to never switch the system off, even in the summertime, as this is likely to lead to a significant need for professional maintenance to clean the ducts. Moisture build-up in the ducts shouldn’t be an issue if the system is properly designed, installed and left switched on year-round. This issue of maintenance can be a sticking point for buildings where the specifier prefers to opt for a system that needs close to none.

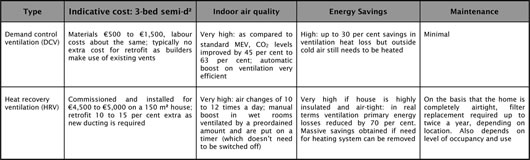

Comparison of ventilation systems in an Irish context

Source: Aereco, Energy Efficient / Lunos and ProAir as compiled by Construct Ireland

For instance Darragh Lynch, an architect with Ballymun Regeneration Ltd in Dublin is installing DCV in the four public housing schemes that are going on site this year: "Some of our residents will be faced with a 'food or fuel' situation in the future and we believe that DCV will best be able to deliver a passive, robust, conventional and low maintenance solution to the energy efficiency requirements we've set ourselves." He says that Ballymun's projects always strive to specify beyond what is required by the building regulations, and in this instance he says they think the build will comply to 2010's targets. "We are far more concerned with implementing a cost-effective and cost-efficient solution rather than getting a high Building Energy Rating. What we care about is installing a good solid system that minimises the fuel bills our residents will have to pay."

In contrast to what can be relatively complex ducting systems associated with whole house heat recovery ventilation systems, demand controlled ventilation is much more straightforward. What it does is respond to the dwelling's ventilation needs in real time by making use of air pressure differences and humidity controls. Humidity sensors are placed on both the inlets and exhausts to respond to room occupancy: the more people in the room the more ventilation you get. The sensors consist of polyamide strips that expand and contract depending on the humidity levels in the room. Humidity levels are a good indicator of occupancy because people sweat, talk, shower and cook, all of which creates humidity. High humidity levels have also been correlated to low indoor air quality, in terms of carbon dioxide levels.

So the humidity sensors do not require an electrical feed to make them work since the nylon-like membranes expand and contract to push the valves open and close. This clearly results in energy savings but that’s not where the bulk of the gains are made. The savings primarily come from not ventilating when not required. In other words, when the room is not occupied there is a minimum trickle of just 5m3/hour airflow through an inlet. According to monitoring studies conducted by DCV manufacturer Aereco the energy savings in France from this end are of the order of up to 40 per cent, while their first simulations conducted in the UK show ventilation heat loss savings of the order of 17 to 31 per cent so far.

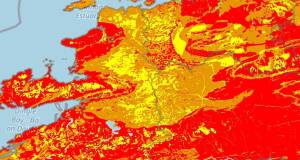

HRV vs. DCV: Comparing energy savings for different climates

Weather-wise Ireland is estimated to lie somewhere between Nancy and Nice, which seems to imply that the energy savings obtained from HRV and DCV are likely to be equivalent in Ireland. When comparing energy savings, it’s important to make sure that the ventilation units are properly sized. An overworked low-energy EC fan can consume more energy than an inefficient fan. For HRV, you’ll need to add an additional unit if your home is bigger than about 300m2.

kWhep/m2/year: primary energy (measured in kilowatt hours) per square meter per year

Source: Association Effinergie

Why the difference? Humidity controlled ventilation systems can be adjusted to suit particular settings. Different climates require different settings as the humidity sensors open and close in accordance to relative humidity levels. That means that the French settings (where ambient air humidity hovers around 40 to 50 per cent RH) won't work as well in the UK and Ireland, where ambient air humidity is much higher (typically 80 per cent RH or more). Aereco argues that these settings can be tweaked by shifting the settings on the actual inlets and exhausts, which they say they've successfully done in Japan. Additionally, the air flows required by regulations are different in every country. Simulation tools such as Siren from the French CSTB makes it possible to simulate ventilation heat losses and indoor air quality in dwellings. The monitoring study has shown how reliable this tool is. Savings in the UK and Ireland can be optimised once all parameters (including weather, typical dwelling and occupancy scenario) are agreed with official bodies.

The French monitoring study seems to suggest something else – that occupants cannot be fully relied upon to ventilate their homes at an appropriate level. During the course of the monitoring study in France, the ventilation system was switched off without telling the tenants. The occupants didn’t particularly feel the need to open the windows even as CO2 levels were rising. That said, CO2 levels never reached any kind of dangerous threshold but they were high enough to suggest the presence of air pollutants. Aereco argues that this proves that there is a need for a ventilation system that responds to room occupancy, as opposed to one that relies on occupancy control such as closable background ventilators or trickle vents. HRV does offer the possibility of introducing a humidity sensor but this system tends to only take a single reading and use it out for the entire dwelling.

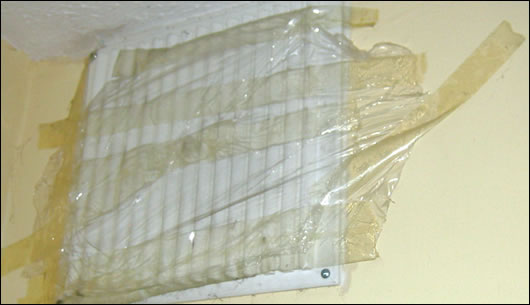

A typical taped-up ventilation grille of the sort found throughout Irish homes. Such vents are often blocked up by occupants experiencing discomfort due to over-ventilation

Demand controlled ventilation may be easier to use than your on-demand TV set, but can it really compete with the ventilation superstar that is heat recovery? As posited here, it all depends on what type of building you have – a poorly insulated home, for instance, is most likely to benefit from DCV. But if you want to do away with all the heating requirements in your air-tight home, HRV is the one to bank on. Then there’s the homes in between which arguably could go either way. It boils down to knowing what kind of building you’re dealing with, and how that all factors in to your budget.

Related items

-

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house -

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems -

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold -

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal -

ProAir retooling for the future

ProAir retooling for the future -

Ecological launch Inventer decentralised ventilation

Ecological launch Inventer decentralised ventilation -

Poor ventilation a Covid risk in 40 per cent of classrooms, study finds

Poor ventilation a Covid risk in 40 per cent of classrooms, study finds -

Efficient ventilation key to healthier indoor spaces – Partel

Efficient ventilation key to healthier indoor spaces – Partel -

Evidence emerges of endemic ventilation regs breaches

Evidence emerges of endemic ventilation regs breaches -

Window-opening unreliable for ventilation, study finds

Window-opening unreliable for ventilation, study finds -

Study confirms “systematic inequalities” in indoor air pollution

Study confirms “systematic inequalities” in indoor air pollution -

International passive house conference kicks off

International passive house conference kicks off