- Ventilation

- Posted

Seal of Approval (John Corless)

In the past, the heating and ventilation of buildings have tended to be considered as separate concerns that come into conflict. As fossil fuel prices rise, the need for energy efficiency in achieving both is increasingly leading Irish people to an approach which combines both ventilation and heating, through making buildings airtight and recovering heat from outbound air, as John Corless explains

Homeowners and businesses are constantly looking at options to reduce the running costs of their buildings. With fuel prices rising and uncertainty in the market it makes sense to minimise the amount of heating required for any property. The air tightness performance of a building can play a huge part in reducing heating requirements.

The term itself - air tightness - is a somewhat confusing one – perhaps air control is more accurate. When we talk of air tightness, what we’re essentially speaking about is the elimination of draughts. In other words when we want fresh air, we open a window or slide the cover of a vent across, and we have the fresh air that we want. Draughty buildings provide fresh air whether we want it or not. In winter when ambient external temperatures may be only three or four degrees and we like to relax indoors in temperatures around twenty degrees, we end up footing the bill for warming-up any incoming air. The less cold air that we have to heat the better – so air tightness, or air control saves money. Airtight buildings offer another economic benefit – they don’t let much warm air escape either.

But ventilating a building can be a more sophisticated procedure than opening or closing a window. Heat recovery ventilation is a process where you not only ventilate but save energy, with heat removed from the air leaving a building and added to the incoming cold air without cross contamination. You still have to add a bit of heat to make up for the loss in the exchanger – although some systems claim in excess of 90% efficiency - and also to compensate for heat loss every time somebody opens an external door. There’s also the heat lost through the walls and roof – even with insulation.

David McHugh set up ProAir Systems in 2004 with a view to producing, selling and installing heat recovery ventilation systems throughout Ireland. With his twenty-plus years experience in the ventilation and general building services industry, he believes the company is well placed to move into what is a small, but growing niche market.

“When we blow up a balloon we create what we call a static pressure inside it. If we then form an opening at the valve which is tiny compared to the surface area of the balloon then all the air will escape very quickly at high velocity,” explains McHugh. “Now if the wind blows against the side of our house, a similar kind of static pressure builds up. Any small openings which exist in the building, such as around window frames, pipes, and so on, will allow air through, in the form of draughts. Currently our Building Regulations stipulate that we have purpose built openings in our walls to allow cold air to go through our homes. These openings are deemed unsightly, uncomfortable, noisy, impractical and highly inefficient,” he adds. “The latest thinking on this subject is to provide a system of building air tightness combined with a heat recovery ventilation system.”

Timber frame buildings use a membrane underneath the plaster slabs known as a vapour check, to prevent moisture from entering the building structure. This can easily be upgraded to an air tightness membrane standard by the use of sealing tapes, mastics and so on, which are readily available. The airtightness of concrete buildings can be improved by sealing around doors, windows, and floor-to-wall and wall-to-ceiling joints. The air tightness performance can then be tested using what is known as a blower door test.

“In a blower door test all of the windows and external doors are closed and any vents closed off. An apparatus fitted to an external door opening will effectively pump up the house to a certain small pressure and then measure the time taken to normalise.” This test will reveal any air leakage points which can then be sealed”, McHugh explains.

“To stay healthy in this sealed environment, we need to take in oxygen, get rid of carbon dioxide, and also expel much of the water vapour which we constantly produce. To do this we need a balanced ventilation system. This is a system which takes in a similar amount of air to that taken out,” he continues. “The problem with a simple fan system is that the air being taken out from bathrooms and kitchen is warm and the air drawn in to bedrooms and living rooms is cold. To overcome this, we bring the two airstreams through a heat exchanger which can recover heat from exiting air and transfer it to incoming air. This, when connected to ductwork throughout the house, is termed a heat recovery ventilation system (HRV).”

When we seal our buildings against unwanted draughts we seal in the moisture which exists in the air inside. This moisture coming from everything from breathing to washing is absorbed by the air until it reaches 100% relative humidity (RH). It can hold no more water at this temperature. It then condenses on whatever cold surfaces it can find like window glass, any cold - bridging points in the building or in the least ventilated areas. Constant slight condensation, combined with dust will result in mould. The primary objective of any ventilation system is to prevent condensation and mould build-up, which is detrimental to both the building and its occupants.

The HRV system does this by taking air in from outside at typically 3ºC and 90%RH. This air is raised to 18ºC and hence the RH reduced to 42%. This means that the air is able to absorb any water generated as it moves from inlet points in bedrooms to outlet points in bathrooms. By the time the air is expelled through the HRV unit its RH would typically have increased to 65% from 42%. Typical cycle time is two hours per air change.

Infiltration of cold air can represent 50% of the total winter heating load in a building. Total heating costs in an airtight building can be 40% less than in a typical leaky building. A well-designed building uses a controllable ventilation system either by mechanical or natural means.

Many of Pro Air’s projects, such as a seventy-house scheme in Sixmilebridge, Co. Clare, and a twenty eight-house project in Westport, Co. Mayo, are small starter units around the 100m² size.

Diane Kirk watches as a blower door test is carried out to measure air tightness in her home

Diane Kirk watches as a blower door test is carried out to measure air tightness in her home

Both developers were keen to embrace sustainable practice and technology irrespective of grants, and were very conscious of the impending Energy Performance of Buildings directive.

“Both Leo McNulty and Padraic Doherty have said to me that they want to sell their starter homes in 2006 with the best rating possible in advance of the 2007 certification. Both men agree that sustainable building is a win win situation for everyone irrespective of the grant. The House of Tomorrow programme has brought them into the scheme and I am confident that they will continue to build sustainably into the future,” McHugh claims.

“We are currently involved in a number of refurbishment projects. In my opinion these people are the real heroes of the sustainable building community and these are the people who should be assisted in any future grant scheme. One particular customer of mine who paid a six figure sum for a suburban 4 bed semi said to me ‘I want to get this right, this is my investment for my old age, and I intend to be taken out of here in a box’. The house is 5 minutes from the Dart station.”

McHugh claims that the house will have gone from guzzling up €2,000 worth of fossil fuels per annum to around €500/annum. “With some help and advice this figure can be brought lower. There are hundreds of thousands of these houses around Ireland and it is in this direction that future grants should go,” he adds.

Chris Montague of Building Envelope Technologies states that his company has seen a huge increase in business in the last 12 months. The company specialises in the commercial building sector rather than dwellings.

“There has been significant uptake by commercial builders,” he says. “Marks & Spencer have been specifying their buildings for air tightness for many years. Dunnes Stores are doing it as a matter of course – it’s in their standard specification for their new buildings. We’re working with a lot of leading architects, developers and builders on different projects.” Montague says that if a building is specified with good conventional details and it’s constructed with a high level of quality, a reasonable level of air tightness will be achieved. “The problem is that buildings aren’t being built to a high level of quality. Timber frame houses are manufactured to high tolerances and the kit is meant to fit together so you don’t get the unforeseen gaps that you get with traditional construction. It’s an engineered product and it’s designed to fit together, so typically timber frame houses return high values of air tightness.”

As Montague explains, any system of air intake to a building has to be some sort of designed system - even if that’s as simple as opening and closing a window. “You want to be able to control the amount of ventilation, where it takes place and when it takes place. If you have a leaky building you have no control over what’s happening - the infiltration just happens when the wind blows and wherever you have the gaps or cracks. By building air tight, you’re reducing the amount of heat loss from cold air leaking in and warm air leaking out.”

Ciaron McCarthy of Mitsubishi Electric Ireland who supply the Lossnay Ventilation system says that their clients include some of the bigger timber frame manufacturers. Like most other heat recovery technologies, the Mitsubishi system takes heat from the stale outgoing air and transfers it to the fresh air in a heat recovery unit.

“This box can be fitted in a utility room or in the attic. Air is drawn in through a duct 150mm – 200 mm in size. No cross contamination takes place - the incoming air does not mix with the outgoing air,” he says.

So how is this air tightness achieved? For starters it’s important to state that the achievement of air tightness is a site issue. Architects are unlikely to include in their designs large or even small holes, and those builders who take the trouble to read the specifications will find nothing stating that there should be unfilled gaps between blocks or bricks in the final product and nothing saying that there should be a good breeze around windows or door frames. So it’s down to the builder.

So what can the builder do at the construction stage to deliver an airtight building? If it’s a timber frame house – and about one in four new homes are –an airtight seal can be created with, for instance, roof and wall breather membranes such as proclima Solitex PLUS, supplied by Ecological Building Systems of Athboy, Co. Meath. This membrane must ‘enclose’ the entire outer envelop of the building including the roof. Joints in the membrane must be taped to ensure a complete seal. Similarly, internally an airtight seal, such as proclima DB or DB PLUS should be fitted over the insulation and bound with seals and tapes, all of which are available from Ecological Building Systems. Even small openings to facilitate electrical cables and larger ones for pipes and ducts must also be sealed. A range of other airtight systems are available in Ireland now, with the most recent addition being the LUP airtight system available through LUP NEROFOL.

This illustration conveys the basic principles of heat recovery ventilation, with the heat from the outbound warm air from wet rooms transferred through a heat exchanger as a preheat for incoming cold air

Masonry houses require a good coat of plaster on the inner leaf of the outer walls, to ensure all joints in blockwork are filled. The ceilings should be sheeted with an airtight membrane as in the timber-framed houses and again small openings must be sealed to achieve airtightness.

The groundbreaking Building Energy Rating (BER) - part of the EU Directive on the Energy Performance of Buildings - comes on stream on Jan 1st 2007 for new residential buildings, with ratings for all buildings when offered for sale or letting/re-letting mandatory after January 1st 2009. This initiative should go a long way towards improving actual building quality standards. The directive contains a range of provisions aimed at improving energy performance in residential and non-residential buildings, both new-build and existing units.

In essence, the Directive obliges specific forms of information and advice to be provided to building purchasers, tenants and users. The intention is that this information and advice will help consumers to make informed decisions leading to practical actions to improve energy performance. For householders, such actions will include energy efficient home improvements and better energy management practices.

The BER certificate - effectively an energy label – must be made available at the point of sale or rental of a building, or on completion of a new building. It is envisaged that the BER will be accompanied by an "Advisory Report" setting out recommendations for cost-effective improvements to the energy performance of the building. In Ireland, the BER is expected to impact on over 150,000 sale or rental transactions per year in the residential market.

In a changing market, with energy performance standards being driven to the fore on the back of legislative changes such as the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, combined with a growing consumer awareness of the need to minimise both heat loss and therefore exposure to exponentially rising energy costs, the importance of preventing unwanted air leakage which undermines energy performance has never been more evident. Consumers who go the airtight approach could find that they not only end up with more cash in their pocket, but are helping to protect the value of their building as the property market changes.

Related items

-

Energising Efficiency

-

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house

Why airtightness, moisture and ventilation matter for passive house -

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems

ProAir pioneers with EPDs for ventilation systems -

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold

Let’s bring ventilation in from the cold -

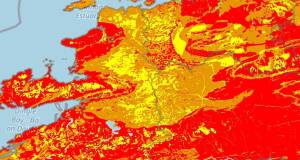

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal -

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced -

ProAir retooling for the future

ProAir retooling for the future -

Ecological launch Inventer decentralised ventilation

Ecological launch Inventer decentralised ventilation -

Poor ventilation a Covid risk in 40 per cent of classrooms, study finds

Poor ventilation a Covid risk in 40 per cent of classrooms, study finds -

Efficient ventilation key to healthier indoor spaces – Partel

Efficient ventilation key to healthier indoor spaces – Partel -

Evidence emerges of endemic ventilation regs breaches

Evidence emerges of endemic ventilation regs breaches -

Window-opening unreliable for ventilation, study finds

Window-opening unreliable for ventilation, study finds