- Wastewater

- Posted

Murky Water

One thing householders don't want to fail is their wastewater treatment system – the pollution, the health hazard, the cost and not least the embarrassment factor are all potentially serious. And yet, one wastewater treatment system provider says that such failures are very likely. As Jason Walsh asks, is he right?

Most companies don't really like regulation. Beyond a simple legal framework in which to operate, legislation is a nuisance. And for good reason: sometimes it forces changes on business practices and sometimes it can wipe out entire product ranges overnight. Most of all, though, it creates administrative and legal headaches that distract a business from its primary activity – selling a product or service.

Consumer activists would give short shrift to such complaints, arguing that protecting the consumer should be paramount. Still, when it comes to regulation, most businesses tend to argue for less rather than more.

And yet, Frank Cavanagh of Biocycle, a developer of a wastewater treatment system, finds himself in a rather different camp. Paradoxically, Cavanagh claims that a lax regulatory regime in Ireland is damaging to consumers, the industry and the environment alike.

According to Cavanagh, current provisions for the certification and control of wastewater treatment systems are not sufficient to ensure that they cause no pollution to the water table.

Fundamental to Cavanagh's argument is that he feels a distinction must be drawn between a wastewater treatment system as a 'black box' and the design and installation of a system in an actual property – the implementation of the overall system, if you will.

"The Department of the Environment's policy on agrément certificates has taken the designer out of the equation. It allows the manufacturer to avoid responsibility."

Cavanagh argues that claims on some agrément certificates that a wastewater treatment system 'will' achieve results gives the impression of false guarantees about the quality of effluent released into the ground: "All you can do is give an efficiency rating for the product, having tested it for an extended period of time," said Cavanagh.

Central to this is the ability of systems to deal with shock loads: "It would be difficult to guarantee wastewater quality in a domestic system," he says. "If someone uses, for example, a dishwasher a lot, flushes old medicine down the toilet, or pours methylated spirits if they've been painting it can wipe a system out for weeks."

According to Cavanagh, attitudes to waste are primarily informed by being connected to a municipal sewage system and that what may be considered normal when on the water mains, can constitute a problem for individual wastewater treatment systems. Thus, he argues, wastewater treatment systems purchased on the basis of claims of effluent quality cited on certificates may lack a suitable back-up in the form of an appropriately designed filtration system.

Thinking of a wastewater system as a 'black box', he claims, causes some to assume that the design of such a filtration system based on the individual needs of a purchaser and local environmental factors is unnecessary. Therefore it follows, he says, that such installations are potential sources of water pollution with backed-up systems releasing untreated or semi-treated effluent into the ground.

"Even a peak load due to [having a lot of] visitors [present at one time] can cause it," he says.

"You need a filter area to do what your treatment system does in these situations. [...] A lot of people don't get into this, they just supply the black box. I feel that's like giving you the car without the wheels. Even if they want to keep it separate, someone has to take [design] responsibility."

Cavanagh further argued that guidelines for wastewater treatment systems have been in draft form for seven years: "The EPA Wastewater Treatment Manual 2000 is a draft document," he said.

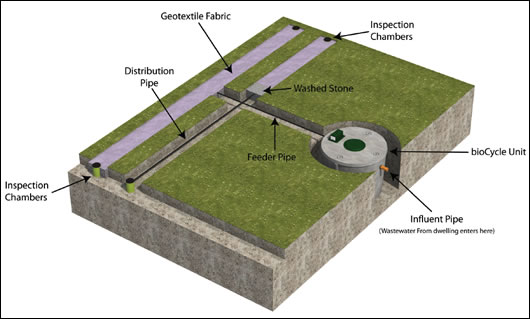

According to Biocycle, a properly designed wastewater treatment and disposal system will have clear access for inspection and maintenance via manhole entry, which complies with statutory safety requirements, along with safety features to prevent spillage of raw sewage on surface, or to ground waters, and prevent unauthorised access. It will also provide access/ inspection chambers to locate and service the polishing/disposal system.

An EPA spokesperson told Construct Ireland that this was not the case, stating: "The manual referred to is not a draft manual. The manual was prepared by the EPA pursuant to its powers under section 60 of the Environmental Protection Agency Act, 1992. This is explained in the Preface to the manual."

However, this is contradicted by a 2003 report on a planning appeal by An Bord Pleanála inspector Breda Gannon, indicating that there is at least some ambiguity over the document's status.

Gannon stated: "The requirements for individual wastewater treatment systems are set out in Appendix 1 of the operative Development Plan which stipulates that they conform with the Waste Water Treatment Manual: Treatment Systems for Single Houses, published by the EPA in 2000. I wish to point out to the Board that this manual is still in draft form and the recommendations set out in “Septic Tank Systems Recommendations For Domestic Effluent Treatment And Disposal From A Single Dwelling SR6: 1991 published by The National Standards Authority of Ireland are therefore applicable."

Cavanagh has also pointed to aspects of agrément certification that he considers to be ambiguous.

Firstly, he drew attention to the following statement found on agrément certificates: "Irish Agrément Board Certificates establish proof that the certified products are 'proper materials' suitable for their intended use under Irish site conditions, and in accordance with the Building Regulations 1997 to 2006."

He then noted that under 'use', the certificate states: "The product is for use in sewage treatment systems designed in accordance with NS 6297:1983 [...] and the EPA Wastewater Treatment Manual – Treatment Systems for Singles Houses 2000 [...]."

Finally, under parts 1.1 (Assessment), he noted the claim that systems, "If used in accordance with this Certificate can meet the requirements of the Building Regulations [...]".

For Cavanagh, 'can' is too ambiguous a term: "If you have built the house and have a well, you want to make 150 per cent sure that you won't pollute your well, or your neighbour's well. You want something more certain than 'can work', you want 'will work'," he says.

"It [an agrément certificate] will give the impression that a system is government tested and certified with a guarantee of performance and durability – that someone is standing over it; a comfort factor.

"When you read it, you realise there's no comfort factor – it's taken away in the small print," he said. "You only read the small print when it goes wrong."

Fundamentally, Cavanagh is arguing that perceived vagueness in both certification and the status of the EPA guidelines allows companies to side-step their responsibility to design systems on a case-by-case basis, instead opting for a 'black box', one size fits all solution.

"Agrément certificates are sometimes presented as evidence that a system has government approval, however agrément certification is based on claims by suppliers, and the Agrément Board accepts no responsibility for system inadequacy or failure. These certificates should be treated with extreme caution as many of the statements and claims in them are untested, unscientific and meaningless," wrote Cavanagh in a statement.

Sean Balfe, manager of the Irish Agrément Board

Accordingly, Cavanagh sees the answer as being located in design: "You need to design a failsafe for the treatment plant – a designed filtration area, a percolation area. A small amount of effluent goes into a [relatively] large area of ground. It's an issue of taking responsibility," he said.

"It comes back to the area of responsibility. It's clouded by agrément because it gives the impression of fitness for purpose. It takes the designer out. The architect should be able to go to an environmental engineer and say 'I want this standard'.

"The same standards also need to apply to septic tanks. 12566-1[is the] European standard for septic tanks. Why did Ireland not adapt that standard, at least for septic tanks?"

Finally, Cavanagh also noted that many agrément certificates are out of date – including BioCycle's – given changes in building regulations since their initial issue.

Wastewater treatment certification

Sean Balfe of the Irish Agrément Board takes issue with Cavanagh on several of his points. In a response to Cavanagh's comments, Balfe wrote to Construct Ireland stating:

"The IAB make every effort to ensure that the end user is educated in the correct use of the systems. We strongly recommend that a competent person be involved in the design and installation of the product. In general people are environmentally conscious and do not dispose of paint thinners etc. into waste water systems. Periods of overloading and dry periods are normal occurrences and all IAB certified systems can cope with this. The IAB have only certified systems that are used in conjunction with percolation areas. The key to this is to educate the end user on the limits and proper use of the system and not attempt to design a system that can cope with every eventuality. If we work on the premise that people cannot and will not use the system correctly then we should revert to using a large septic tank as this will ensure minimal environmental damage.

"Mr. Cavanagh gives the impression that the IAB suggest that certification means the [wastewater treatment system] will suit every situation. This is not the case and it is important that the certificate be read in detail to ensure the correct use. All our certificates are available at www.irishagrementboard.com."

Balfe also disputes Cavanagh's assertion that many of the agrément certificates have gone out of date:

"The purpose of agrément is to certify innovative construction products. The IAB held an industry forum in 2003 where we invited participants from the Department of the Environment, Local Authorities, DETE, EPA and other interested parties. From this an agreed testing regime was established. Whilst we ensure this testing is carried out prior to issuing an agrément certificate, we recognise that the performance of the materials in the market place is a valuable test of the efficacy of the product. A five year period allows us to review this performance and also to consider any manufacturing changes or changes in the performance demands from the user, prior to reissuing the certificate. IAB introduced the five year contract in 2004. All certified products are subject to annual review to ensure they are in continued compliance with the certificate; therefore all certificates currently published on our website are valid, including ones more than five years old."

Balfe's statement of annual reviews contradicts an assertion by Cavanagh that Biocycle has not been audited by the Agrément Board more that three times since the early 1990s. To this Balfe responded: "In the late 1990s and early 00s there were little or no audits due to limits on staff resources. The IAB are part of the National Standards Authority of Ireland, who operates an ISO9002 quality system. Biocycle are registered with the NSAI and have an auditor visit their facility at least once per annum. The IAB audit would be a similar audit to that carried out by the NSAI. Generally, IAB audits are being carried out annually now and we have withdrawn certificates for breach of conditions."

Given that agrément certificates are stating actual treatment performance characteristics (expressed in terms of BOD, phosphates and so on) there is some question over whether the certificates certifying that those characteristics will be achieved. How can the Agrément Board certify treatment performance characteristics given that domestic dwelling effluent can be hugely different in each application?

Balfes view is that exceptional and, ultimately, incorrect use of wastewater treatment cannot be covered in the certification process: "Human effluent is not 'hugely different' in each application, rather its characteristics remain reasonably constant. IAB certified products are capable of treating average domestic effluent which would constitute over 80 per cent of installations in our experience. Some differences in domestic effluent arise due to the use of household appliances, cleaning products and detergents etc. The IAB insist that the manufacturer of any certified product explains fully to the end user, the type and volume of waste that the unit is designed to handle. Our certificates also state the conditions that the unit is designed for and that a 'competent person' be consulted to advise on the wastewater treatment requirements for each installation. Ultimately it is the users’ responsibility to ensure that they purchase and install a unit that satisfies their particular needs. People will be familiar with the wheelie bin issued by local authorities, one size is suitable for 90 per cent of houses but some households produce more solid waste than normal and therefore need a bigger bin. Like any other piece of mechanical equipment, if it is not used correctly, it will fail to function correctly."

Clearly appropriate monitoring and maintenance is of vital importance to a wastewater treatment system, ensuring that no pollutants are escaping untreated into the water table. However, with many of the certified systems, access is restricted, potentially making it impossible to access the system to either monitor its performance or replace components.

"In our experience this is not the case," wrote Balfe. "These systems require open space to operate properly and that is shown graphically on the certificate. They require percolation areas, regular maintenance, de-sludging, etc. The IAB certify that the system will perform if installed and used properly as described on the certificate, we recommend that a competent person be engaged to advise on the installation etc."

In response to questions over what legal responsibility the IAB takes on due to agrément certificates stating "that [...] certified products are ‘proper materials’ suitable for their intended use under Irish site conditions, and in accordance with the Building Regulations," Balfe wrote: "Irish building regulations state that one way of showing that a material is a 'proper material' is by complying with an Irish agrément certificate. Over 80 per cent of product failures in the construction industry are due to inappropriate use or poor installation. The IAB do not and cannot certify the installation, however we do offer installation guidelines in the certificate. In the case of waste water treatment systems the IAB are stating that it is their opinion that if the product is manufactured correctly, installed and commissioned correctly and finally used for the purpose for which it is designed, then it will function correctly. Regarding the legal responsibility that would be a matter for the courts to determine should it arise."

Construct Ireland contacted Conor Linehan, a partner at law firm William Fry who heads the company's environmental law practice.

Conor Linehan, head of William Fry's environmental law section

Linehan's work covering the legal aspects of waste management, planning and land-use, pollution control licensing, contaminated land issues, habitat conservation and protected area controls, is conducted in a variety of settings including environmental due diligence, ongoing regulatory advice, court hearings as well as planning oral hearings.

Linehan told Construct Ireland that there is some uncertainty around the issue: "Having regard to the undoubted 'marketing tool' value going with IAB certification (both perception-wise and in practice) and having regard to scope for the holder of a certificate to represent fitness for purpose through the presentation of a certificate, some aspects of certification – in particular the form of the certificates and how they feature on the IAB's – may be questioned," he wrote.

"An important point in this regard relates to the difficulty in determining the current status of certificates. The initial impression (from the existence and holding of the certificate itself) is that certification is current and up to date."

"The uncertainty derives not from the inclusion in the certificates of exclusion clauses [or] disclaimers. There is a standard clause disclaiming legal liability to persons suffering loss or damage through the use of a product bearing IAB certification through which the Board seeks to emphasise that it is ultimately a certification body and does not, through certification alone, create direct legal relations or incur potential liability to individual consumers and purchasers," he wrote.

"Rather the lack of clarity stems from the particular wording of particular 'conditions of certification'. Certificates for example state that they shall "remain valid so long as [...] the product continues to be assessed for the quality of its manufacture and marking by the NSAI". This introduces an element of subjectivity (in the absence of transparent and clear assessment criteria [and/or] practices) and uncertainty on the face of the certificate itself."

Linehan also questioned the status of some of the agrément certificates which refer directly to now outdated regulations: "This uncertainty, it is suggested, is not easily or in practical terms resolved by the inclusion elsewhere in the certificate of a note informing readers that they 'may check the status of (the) certificate has not changed by contacting the [Board]'.

"An important purpose of the certificates is the role they play in demonstrating compliance with relevant requirements of the Building Control Regulations. While all the waste water treatment system certificates on display on the IAB's website appear to state in one way or another (although not always in the same way) that the requirements (as regards materials, drainage etc) of the Building Control Regulations are met, in the case of some certificates the reference is still to compliance with the "Building Regulations 1991". The 1991 Regulations were revoked in 1997.

"The failure to have an up to date legislative reference on the certificate would be immaterial, except that the outdated reference here appears in a condition relating to continuing validity of the certificates. The particular condition states that the certificate '...shall remain valid so long as .....the Building Regulations 1991 and Standards affecting the subject remain unchanged'," wrote Linehan.

He goes on to state that simply arguing that the 1997 certificates contain the same provisions as their 1991 predecessor does not resolve the issue: "Again, the 1991 regulations are long since revoked. The fact that the replacement (1997) Regulations contain essentially the same requirements on materials, drainage and waste disposal as did the 1991 Regulations does not, on the exact terms of the certificate, wholly resolve its status. It is not fanciful to suggest on the wording of the continuing validity condition that the certification ceased with the replacement of the 1991 Regulations."

Accordingly, Linehan questions the current certification methodology: "All of this highlights the need for a system or method of continuing certification that depends on frequent and transparent monitoring, assessment and certificate updating (thereby ensuring that certificates bear the most unequivocal and unqualified wording possible) that on a system where, on the face of the certificates themselves, continuing certification/validity is expressed to hinge on specified legislation continuing in force and/or on ongoing assessment by the Board of the certificate holder. If the Board is engaged in regular ongoing assessment of certificate holders and of systems then surely it is more user-friendly (from the public's point of view) to have certificates reflect that (through regularly updated certificates), again, to have the continuing validity of the certificate tied in with and dependent on unspecified background assessment”.

Ultimately Frank Cavanagh's criticisms appear to be reasonable concerns. However, the Irish Agrément Board's responses are not themselves unreasonable. At the very least, it is possible to say that the area of the efficacy of wastewater treatment systems, and legal responsibility for them, is opaque.

It appears that there is a case for increased clarity in the sale of wastewater treatment systems. From the perspective of a consumer, clear guarantees applied to a product must be backed up by legal recourse. Should a system fail to live up to any guarantees, then the issue of responsibility is paramount and, in this case, responsibility must ultimately lie with the manufacturers and installers of wastewater treatment systems.

- Articles

- wastewater

- Murky Water

- wastewater

- treatment

- certification

- health hazard

- sewage

- septic tank

- agrément

- filtration

- percolation

- effluent

Related items

-

BaseTherm liquid floor insulation gets Agrément cert

BaseTherm liquid floor insulation gets Agrément cert -

Partel’s Izoperm Plus achieves passive house ‘A’ cert

Partel’s Izoperm Plus achieves passive house ‘A’ cert -

Earth Cycle expands into PH education & training

Earth Cycle expands into PH education & training -

Learn about wastewater heat recovery remotely

Learn about wastewater heat recovery remotely -

KORE gets NSAI cert for insulated foundation

KORE gets NSAI cert for insulated foundation -

Glavloc awarded Agrément certificate

Glavloc awarded Agrément certificate -

Passive Sills get BBA cert

Passive Sills get BBA cert -

Beam Vacuum & Ventilation awarded three new ISO certs

Beam Vacuum & Ventilation awarded three new ISO certs -

Keystone’s Hi-therm+ Lintel receives BBA cert

Keystone’s Hi-therm+ Lintel receives BBA cert -

Passive Sills gets Agrément cert

Passive Sills gets Agrément cert -

Amvic Ireland ICF gets updated Agrément cert

Amvic Ireland ICF gets updated Agrément cert -

Skills-shortage and assigned certification - the devil is in the detail

Skills-shortage and assigned certification - the devil is in the detail