- Blogs

- Posted

Is affordable housing a policy blind spot?

Dublin City Council built just 45 social housing units in 2019. In his latest column, Mel Reynolds analyses the state’s surprising reluctance to build its own homes.

This article was originally published in issue 36 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

Industry reports have suggested modest house price falls in 2020. Private equity fund purchases of entire schemes have resumed and land values continue to be bid up, albeit with fewer transactions. Ireland’s ‘low supply / high price equilibrium’ housing market appears impervious even to a global pandemic. When the shadow of Covid-19 begins to fade next year imbalances in the housing sector will again become apparent.

Official policy inertia surrounding affordable housing makes the problem appear insurmountable. However, it is not.

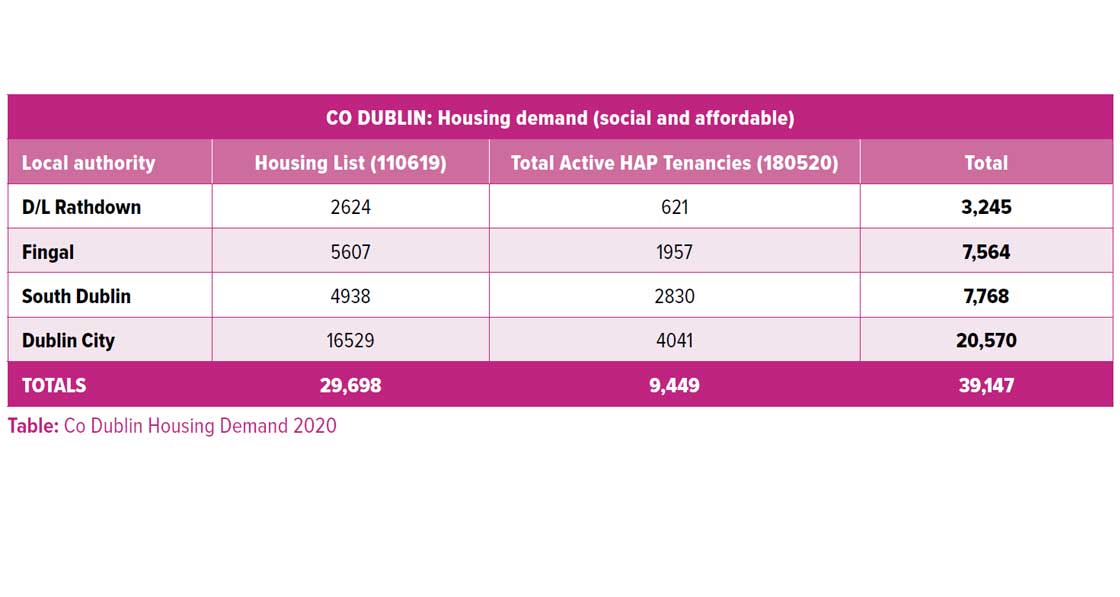

The best metric to illustrate demand for affordable and social housing is the combined housing list and Housing Assistance Payment (HAP) lists. These show how many households have been waiting for social housing for years and how many households are currently receiving rent assistance in the private rental sector. With the exception of South Dublin, availing of HAP means losing your place on the housing list, so a combination of both lists gives a good indication of households on more modest incomes (less than €18,000 per annum) that need social and affordable housing. The total nationwide demand figure as of May was more than 124,000. In County Dublin, the location of greatest housing need, the demand figure is 39,000.

The best metric to highlight state intent, where the state controls the entire process — owns land, can get planning permission quickly, avail of ultra-cheap finance and develop housing directly — is local authority builds, where the state acts as developer. There are other forms of procurement, but many take years and are far more expensive (such as the O’Devaney public private partnership (PPP), which I discussed in this column in issue 32 of Passive House Plus). Recent figures from both the Dáil and the Department of Public Expenditure and Reform confirm that the state can develop directly at half the cost of buying new homes.

The total figure for local authority builds in 2019 was 1,088, and just 228 were built directly by the four Dublin local authorities. This figure is less than in 2018 when the state completed 1,238 local authority builds. Remarkably Dublin local authorities built 232 social houses in 2017, more than in 2019.

The example set by Dublin City Council illustrates the gulf between demand and continued official inertia. In Dublin City there is a social and affordable demand of more than 20,000 households while in 2019 the City Council’s build output was just 45 units. Of this total, 24 were refurbished apartments at Priory Hall, rebuilt for €141,000 per unit and not new builds at all. (Nineteen of the remaining 21 builds were so-called ‘rapid’ units where DCC paid a premium of €384,000 per unit, more than 25% above the average cost in County Dublin of standard local authority homes built in 2019.)

In contrast, Dublin City Council owns 112 hectares of zoned residential land with capacity for well over 10,000 homes. They are currently utilising just 0.01% of this capacity. The scale of local authority underperformance across the board suggests systemic issues with official policy and the Department of Housing.

Dublin City Council has been in the news for the failure to get its proposed PPP regeneration scheme at Oscar Traynor Road off the ground. Councillors voted down proposals to hand over a large tract of land owned by Dublin City Council to a private developer.

Remarkably, County Dublin local authority build levels are falling.

The deal was broadly similar to the one at O’Devaney Gardens, where a portion of units will be made available to the state to purchase as social housing and to be heavily subsidised as affordable housing for sale to those on more modest incomes.

Back in the early noughties, PPPs entailed the state handing over a site to a developer and getting units back for free as social housing. These days the site is handed over and the state ends up buying back social housing while paying a premium. PPP deals of this nature are very complex, take years to get going and are remarkably poor value for the taxpayer.

Government reliance on turnkey purchases, where the state and approved housing bodies (AHBs) buy directly from the private market, has increased to 25% of all new homes built nationwide in 2019. Government policy to purchase at this scale rather than build directly has become a systemic risk to the new housing sector.

Where the state is renting, in areas of high demand such as County Dublin, the cost is more than double the cost to build directly. In Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown, the average annual cost to rent a Part V dwelling had doubled from 2017 to €28,310 per year in 2019.

The state is increasing social housing stock by buying from the private sector. In areas of high demand this is twice the cost of direct build on state land. When not purchasing, the state is subsidising thousands of private tenancies and driving rent inflation.

Excluding other semi-state bodies, between NAMA and local authorities, the state controls enough land to build more than 70,000 dwellings.

In County Dublin the state controls 50% of all zoned residential land. Remarkably, County Dublin local authority build levels are falling. It would appear that the government’s continued unwillingness to support local authority direct procurement not only defies logic but is a massive cost to taxpayers.