- International

- Posted

International Selection - What we can learn from igloos

Nothing drives innovation like adversity. Facing up to the prospect of scarce energy and other resources, we can take inspiration equally from the Inuit and the most avant-garde of passive house designers, as Sofie Pelsmakers reveals in her choice of six uniquely inspiring buildings from around the world.

I believe that all good architecture should also be sustainable architecture and I hope that my selection of buildings illustrates this very point. The six dwellings I have chosen inspire me for several reasons: from the Inuit’s igloos as bare shelters with minimal impact to advanced passive house buildings. They share some remarkable strategies such as reliance on body heat for internal heat-gains and good airtightness and – in the case of the Just-K passive house – also the utilisation of the natural stratification of air. Le Corbusier’s 1950’s Maisons Jaoul with Catalan vaults and rough brick is not well known but well-loved by its current inhabitants (two families with young children, since you ask). Like the majority of buildings at the time, the Maisons Jaoul are uninsulated apart from double glazing, but use the local site context and the European material vernacular of brick and oak beautifully. Pushing the local vernacular and local material opportunities further are Geoffrey Bawa with his tropical, bioclimatic modernism in Sri- Lanka and the sublime Tyin Tegnestue with their architecture of necessity, built with and for local communities with limited resources.

I think my selection of these projects gives away what inspires me most: buildings which quietly mitigate and adapt to climate change, which use local materials and skills intelligently while drawing from local knowledge, skills and techniques. I particularly get excited by those projects which use contextual parameters to generate their design rather than see it as a straitjacket for creativity, and all projects presented here do exactly that, though each in very different ways. But I also believe, just like the Inuit when constructing igloos, that we have to gain a deeper knowledge and understanding of locally available materials and construction sequences and techniques for how we design and build.

Qaaviganguaq Qissuk, an old hunter Inuk uses a snow knife to build an igloo in northwest Greenland

Igloos,

the North American Arctic

Igloos were temporary hunting shelters built by the Inuit population in northern Alaska, Greenland and Canada, and are only sporadically used. Igloos are built from local and renewable materials with just a knife for cutting and shaping and can be erected by two people in less than two hours for a night’s shelter to two days for a larger one, where several igloos of different sizes are connected to provide more space and greater comfort. They are built from 20 cm thick snowblocks, cut out with a knife from the snowy ground surface. To do this, sufficient snow depth is needed, so blocks can be cut out of the surface and lifted out, leaving the igloo’s floor one snowblock below the external ‘ground’ level.

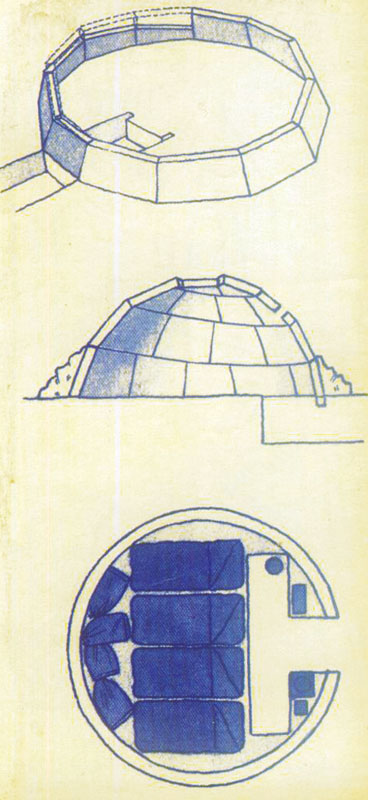

Diagram showing how the sleeping area is raised above the entrance so that it retains any heat as hot air rises

The first snow-block layer is put in a circle and its height cut down to a sloping spiral before placing the next layer of snow-blocks, giving it inherent strength. The igloo can then be built entirely from the snow found within its ‘circle’. Light can be allowed in when using ice-blocks instead of opaque snow-blocks.

Airtightness is crucial and blocks are shaped with a knife to create tight joints between them. Once all the snow-blocks are in place, cracks are plugged with snow from the outside. The effect of breathing inside creates an ice layer and an airtight layer while also strengthening the structure. Natural stratification allows the warmer air from people’s bodies to move up into the main igloo space at the top, which is used for sitting and sleeping, often made comfortable with animal skins. A very small gap at the top is allowed to replace CO2-laden air with fresh air from a small hole under the lower level entry tunnel, which is closed with a snow-block. Due to the airpockets in snow, it acts as an insulator in a harsh environment. This combined with a small, compact space and body heat in an occupied igloo, creates relatively warm internal temperatures of around 15C. Though much below the thermal comfort that we have come to expect from our dwellings at present, this is an impressive increase from external temperatures which are several degrees below zero.

Yet the lessons from igloo-building are relevant, but often ignored, in today’s construction in cold climates: the importance of airtightness, wind protection, dwelling occupancy and harnessing of internal heat gains. Too often have we allowed the outside in when it is not desirable and we still are bad at providing protected lobbies or wind-shelter. Igloos also teach us lessons about the use of local materials, construction techniques and knowledge, unrivalled by most architects or builders. Architects are generally removed from the construction process, while builders seem to build each house as a one-off prototype, not able to take forward knowledge and skills gained.

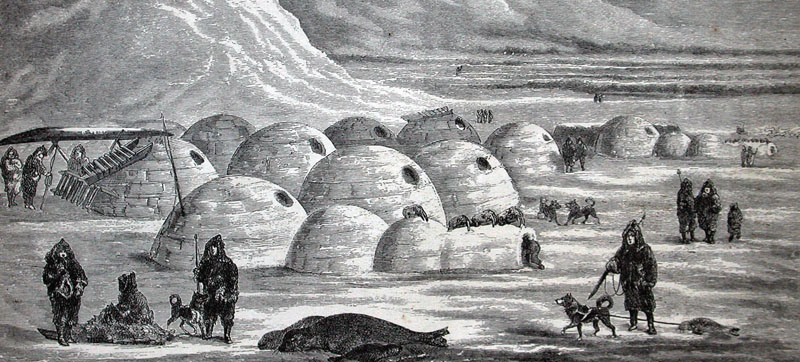

A community of igloos (Illustration from Charles Francis Hall's Arctic Researches and Life Among the Esquimaux, 1865)

Just K,

Tübingen

Just K was designed by Amunt Architects in Germany for a family of six people. Just Iike the igloo, the living spaces are at the top, and natural stratification ensures that these are the warmest spaces in winter. As in igloos, good airtightness is crucial to reduce heatloss through cracks and the passive house standard has been adhered to.

Its sculptural form was generated from its contextual and constricted site conditions, such as needing to allow original views from neighbouring dwellings to the vista’s beyond. An efficient building fabric was achieved partly by prefabrication and high levels of insulation, as well as solar gain to harness the free heat and light from the sun, while the sculptural form leads to a vertically connected open space within a limited volume. The house can be split into two apartments and is built almost entirely from locally sourced timber and prefabricated in a local factory with a total of 136 pieces site-assembled.

The structural engineered timber has been left bare internally, providing a warm and architecturally interesting interior, while adding significant thermal mass to the fabric. The use of timber and vertically connecting spaces with strategically placed openings, creates a fluid interior. Its spaces resemble something very different from what we have come to think of as highly efficient dwellings and is hence inspirational in breaking this mould.

Haren 02,

Brussels

A re-interpretation of the efficient ‘box’ is also what A2M Architects did in Haren 02, which is a residential scheme of 30 passive house dwellings in the north east of Brussels, where from 2015 all new buildings will need to meet the passive house standard. The architects took great care to design its urban form and generated ‘urban breaks’ – a vertical stepping of buildings to break regularity and allow for a less imposing street front. They also allow for solar gain and views to internal and external spaces beyond, while creating accessible roof terraces for residents. Rather inspirationally, the architects consciously decided a few years ago to only accept passive house commissions as they believe this is simply common sense. They also undertake all of the building physics and technical modelling themselves rather than outsourcing it, thereby creating a local hub of knowledge in their day-to-day practice.

Haren 02 is currently on site, and is likely to be a game-changer for passive house in Europe and elsewhere for several reasons. Firstly, the project is projected to cost around 15% less than standard housing construction, achieved by prefabrication and as much offsite construction as possible to avoid wet trades and speed up construction to around seven months. Secondly, Haren 02’s projected primary energy use is just 45 kWh/m2 per year – due to its passive house specification and some on-site renewable energy delivery. Once completed, the performance will be monitored. In addition, some of the dwellings are ‘zero energy’ prototypes, illustrating that energy efficient buildings require less energy. Indeed, it is much easier for the remaining energy requirements to be met with renewable technology, whether on or off-site, in efficient buildings.

Finally, Haren 02’s airtightness strategy is potentially more robust and longer-lasting: it relies on the use of prefabricated concrete panels without the need for airtightness membranes or tapes (joints will be siliconed instead, however the longer term performance of this approach is unconfirmed). Such thinking may spur the construction industry to go further still in working with the inherent qualities of materials to achieve airtightness more naturally, so watch this space.

Maisons Jaoul,

Paris

In principle, I normally only write about buildings that I have visited: there is no substitute for spending time in a building to experience and judge its qualities such as its scale, volume, fluidity and changing light conditions and to gain a sense of how the building is used and has weathered. However, the only buildings included here which I have visited are the Maisons Jaoul by Le Corbusier, in the outskirts of Paris.

The two Jaoul family houses are far removed from Le Corbusier’s earlier and well known designs such as Villa Savoye or Maison La Roche. The Jaoul houses were designed in the early 1950’s, in Le Corbusier’s more mature years, and it shows: the use of primitive techniques combined with modern technologies such as thin Catalan vaults on thin load-bearing and rough brick walls with exposed rough concrete, bright colours and plenty use of timber and sod roofs. In fact, there are no external super-smooth white finishes in sight at all.

The vaults act as central hearths and refer to primitive human habitations and shelters and were regularly used by Le Corbusier in his later dwelling designs. The placement of the two houses on the constrained and overshadowed site were generated by Le Corbusier’s search for the greatest amount of exposure to sunlight and daylight penetration. Typically, the windows sit in window sections (‘pans de verre’), with glazed sections for day-and sunlight and opaque timber sections to provide ventilation openings and built-in furniture. Internal timber wall panels also act as ‘aerateurs’ to provide fresh air, located between spaces to allow for cross ventilation, while retaining privacy. Moving timber shutters keep the heat in on cold winter nights and make the house light or dark and all stages in between. One of the houses has beautiful rainwater spouts and some innovative L-shaped windows were developed in response to strict bylaws. A tile is cast in the original tiled floors with instructions to occupants for how to maintain it, a front-runner to occupant user-manuals, if you like.

The combination of traditional and modern evident in the Catalan vaulted ceilings, thin load-bearing walls and sculptural stairs

Unfortunately the early double glazing failed and the current occupants say it is difficult to keep warm in a cold winter as it was built before insulation, thermal bridging or high thermal comfort standards mattered. Yet the Maisons Jaoul signify an important shift from Le Corbusier’s much earlier work and are a departure from the generic, standardised international modernism to a more regional and contextual approach that most do not remember the iconic architect by. This maturation was inspired by his interest in the local vernacular but also by learning and responding to building feedback and mistakes, something all designers should be doing.

Ena Da Silva house,

Colombo

Geoffrey Bawa was influenced by international modernism and Le Corbusier’s early work and in the late 1950’s designed tropical ‘modernist’ buildings in Sri Lanka, though little known outside South-East Asia. While white, reflective surfaces suited a hot, humid climate, Bawa soon realised that pitched roofs with large overhangs rather than flat roofs were better to deal with torrential downpours, keep the sun out and to encourage natural ventilation.

From his interest in Sri Lanka’s architectural heritage and building traditions, Bawa developed tropical courtyard designs with open spaces around them to aid natural airflow and the Ena Da Silva House, built in 1960, is an example of this. It signifies Bawa’s deeper understanding of local climatic conditions and material use and blends modernity and tradition. Pitched roofs are tiled with traditional materials while timber trellises provide screened views across the courtyard. Inside and outside spaces are blurred, giving the feeling of infinite space and providing a good cross flow of air. Bawa beautifully builds on the local vernacular, utilising principles of cross flow of air, courtyards and shading, to provide modern, bioclimatic architecture with spaces that work and are inspirational.

Soe Ker Tie House,

Tak Province

Norwegian architects Tyin Tegnestue follow in the tradition of the likes of Rural Studio, virtuously working for and with local communities, including utilising community skills during design and construction. Among their many inspirational projects I chose Soe Ker Tie House (Butterfly House) which was built in just six months and for just $11,500 USD. They exchanged skills, techniques and knowledge with the local community, with whom they designed and built six dormitory houses for Burmese orphanage refugee children on the Thai- Burmese border. Unlike most designers, Tyin Tegnestue were also involved in the construction process, providing a critical learning and feedback loop.

The six butterfly houses are built in timber with a raised floor, using traditional bamboo weaving techniques and locally sourced bamboo for the facades. The butterfly shaped, lightweight tin roofs allow water to be collected in the rainy season for use in the dry season. Bamboo is also utilised as ‘honeycomb windows’, giving security, privacy and light but also natural ventilation and solar shading. At higher level, openings with timber shutters are provided for further air breezes while providing solar shading. The result is playful, beautiful and sustainable and the product of sharing of knowledge, skills and creative forces with the local community. This is inherent of most of Tyin Tegnestue’s work: they tend to work in areas of need, with the local community directly involved in the design and building, and they establish a mutual learning process. Due to the nature of projects and constraints of budget and remoteness, local materials and skills are utilised from project conception to completion. Rather than as acting as a constraint, this has helped generate a new, local vernacular architecture which is truly delightful. Like the Inuit igloos, local materials have to be used within limited budgets and time constraints. Yet the architectural results are refined and poetic, despite (or thanks to?) it being an architecture of necessity.

Of course the beauty of their work is in part due to the rethinking of traditional and local materials and the local vernacular, which demands in a hot, humid, tropical environment for air to flow freely in buildings and between spaces to provide thermal comfort. They reinvented locally available materials and techniques to do exactly that, to a stunning effect.

- Igloos

- Just K, Tübingen

- North American Arctic

- airtightness

- Haren

- Urban breaks

- Maisons Jouls

- Ena Da Silva house

- Soe Ker Tie

- Issue 2