- Marketplace

- Posted

Focus on better buildings, not better spreadsheets

This article was originally published in issue 50 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

The UK’s sustainable construction industry has become dangerously addicted to data at the expense of human judgement and practical performance, according to Kirkman, a leading industry figure who warns that the obsession with metrics is actually harming innovation.

Kirkman argues that the sector’s reliance on spreadsheets, dashboards and compliance tick-boxes is creating a “false sense of precision” that obscures what actually matters in building performance.

“We’re building better spreadsheets, not better buildings,” he says, whose company supplies sustainable building materials. “The most important variables in construction are often the ones that can’t be measured - trust, installer confidence, whether occupants feel proud of their home.”

The critique comes as the construction industry faces mounting pressure to meet net-zero targets whilst grappling with a housing crisis that demands both speed and quality. Yet Kirkman suggests that the industry’s response - ever more sophisticated data collection and analysis - may be part of the problem rather than the solution.

“What gets measured gets managed – but not always well,” he explains. “If only U-values are tracked, we optimise for U-values. If SAP ratings dominate design decisions, we design for SAP – not necessarily for performance.”

The phenomenon, which Kirkman dubs factory-forward thinking, prioritises metrics that can be easily calculated and compared – thermal performance, cost per square metre, embodied carbon – over contextual factors that determine whether buildings actually work for their occupants.

This approach, he argues, systematically disadvantages innovative materials that may perform better in real-world conditions but don’t excel in single-metric comparisons. Hemp insulation, for instance, might have a marginally higher thermal conductivity than synthetic alternatives but offers superior moisture management, air quality benefits and environmental credentials.

“Imagine the distress of a product inventor who has spent years developing a highly engineered insulation product with improved moisture regulation and carbon sequestration. Yet the only thing that gets noticed is the U-value, which might not fully represent the product’s superior performance in other critical areas,” he says.

The problem is compounded by a compliance ceiling - where minimum regulatory standards become de facto targets rather than baselines to exceed. This creates a culture where innovation is actively discouraged because it introduces uncertainty into systems designed around familiar metrics.

“Compliance demands provable outcomes, regulation locks those outcomes into policy, and established practice reinforces what’s already familiar,” Kirkman says. “Together, they create a default operating system that is deeply resistant to change - even when that change would lead to better buildings.”

The human cost of this data-driven approach extends beyond innovation. Kirkman points to a lengthy list of factors crucial to construction success that resist quantification: trust between supply chain partners, installer confidence, post-occupancy comfort and “whether a building is easy to live in”.

“These are the human, behavioural, emotional factors that often determine whether a building works in the real world,” he says. “Their absence from spreadsheets doesn’t make them unimportant - it makes them more important,” he said.

The solution, according to Kirkman, isn’t to abandon data but to restore balance: “We need to use data to augment human decision- making rather than replace it. We need to give people space to make judgement calls, even when data doesn’t provide a definitive answer.”

The challenge is particularly acute for sustainable construction, where the pressure to demonstrate environmental credentials through measurable outcomes can overshadow the nuanced benefits of truly innovative materials and approaches.

“The real question,” Kirkman says, “is whether we’re willing to trust human judgement again, or have we let data become the sole authority?

Products for people

While the industry grapples with data overload, one company is taking a different approach by focusing on the human element that spreadsheets can’t capture.

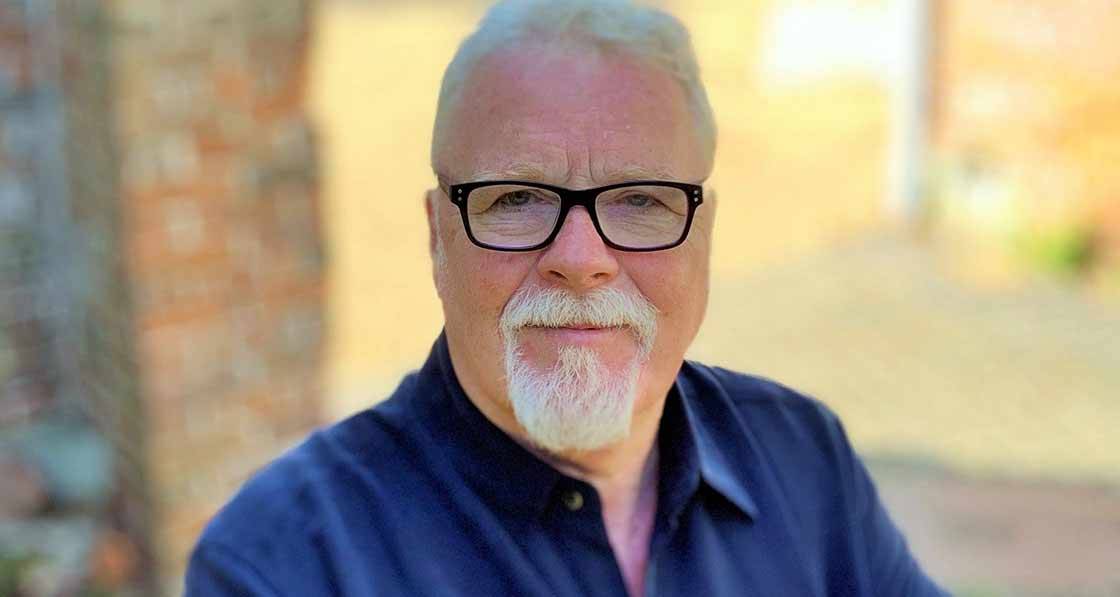

Ecomerchant, a supplier of sustainable building materials, has built its business model around what managing director Will Kirkman calls “shelf-backwards thinking” - starting with people’s needs rather than product specifications.

“We recognise that the biggest barrier to sustainable construction isn’t technical - it’s human,” said Kirkman, “Builders are often hesitant about unfamiliar materials, whilst homeowners want healthier, more energy-efficient homes but struggle to find contractors willing to work with natural products.”

Rather than simply supplying materials, Ecomerchant positions itself as a bridge between client vision and builder expertise, providing technical support and reassurance to help tradespeople confidently work with sustainable materials.

“It’s about trust and confidence - things you can’t put on a spreadsheet,” says Kirkman. “When builders feel supported and clients feel heard, you get better outcomes than any amount of data can deliver.”

The approach reflects the company’s belief that successful construction depends more on relationships, communication and shared understanding than on optimising individual metrics.

“We’re not just selling products,” Kirkman adds. “We’re facilitating conversations between people who want the same thing - buildings that actually work.”