- Opinion

- Posted

Dead Cert

Everyone agrees that the standard of building materials must be maintained but is localised technical certification resulting in a death of innovative and environmentally friendly building products and systems reaching the Irish market? Construct Ireland's Jason Walsh & Jeff Colley investigate.

Construction standards are one of the most pressing matters in the building industry, not only in terms of the quality of the construction process, architecture and engineering on-site, but also in the engineering of the materials which are used to build. After all, if the materials from which a building is constructed are not sound, there is little chance that the building itself will be. In Ireland today it seems fair to say that there is something of a mass of competing technical approval standards for products where there is no European harmonised standard. Pan-European standards are governed by EOTA, the European Organisation for Technical Approvals, based in Brussels. European Technical Approval (ETA) for a construction product is a favourable technical assessment of its fitness for an intended use.

ETAs allow manufacturers to place CE marking on their products, thereby assuring buyers that the product is fit for purpose. Meanwhile, the Irish Agrément Board issues its own agrément certificates. According to the Irish Agrément Board, agrément certification is "designed specifically for new building products and processes that do not yet have a long history of use and for which published national standards do not yet exist." Finally, both BRE Wimlas and British agrément certification are common in Ireland.

European Technical Approval

EOTA's European Technical Approval offers a direct alternative to local standards certification.

"It’s a kind of building passport," says Paul Caluwaerts, Secretary General of EOTA. "It’s a technical specification of your product which gives you a kind of technical passport for your product, but it’s an individualised document. It’s a document for one manufacturer and one product or product range of that manufacturer."

One manufacturer of an innovative building product told Construct Ireland that his firm saw agrément certification as purely a marketing measure, a stamp of approval that makes purchasing easier for architects and engineers. The common perception on the ground is that an agrément certificate is required for any new and innovative product brought to the Irish market, and that otherwise it would be near-impossible to use on a build due to difficulties obtaining insurance. Homebond, a private company who have long held a majority share of the residential structural insurance market in Ireland, are reputed to not allow products without agrément certification to be used in developments on which it is the structural insurance provider. The irony here is that this means new products are subject to more rigorous standards than older ones, including those now considered unsuitable by many. This has led to a situation where building products such as the 9" hollow block, unused in domestic building in most western countries—and reported in a Dáil debate as long ago as 1978 as being banned in UK and "most unsatisfactory from the point of view of house building here"—are de facto permitted in the Dublin area. Premier Guarantee, an alternative scheme, takes a rather different view. For Premier Guarantee, any product with European Technical Approval can be used in the construction process, thereby mitigating the need for agrément certification. Bob Williams from Campagna, the firm that provides engineering assessments for Premier Guarantee in Ireland says: "Yes, agrément certificates are acceptable but [if we see] other test certificates from other recognised bodies, we will consider the materials."

At present, EOTA has a range of ETAs for construction products: "We have ETAs for innovative thermal insulation materials for example, where not covered by harmonised standards, we have ETAs for special anchor types, we have ETAs for prefabricated buildings because a prefabricated building is considered by the Construction Products Directive as a product which is brought to the market," says Mr. Caluwaerts.

Asked whether European Technical Approval has the same status as national agrément certification, Mr. Caluwaerts said that it does: "In reality it is an enlargement of this because national agrément is there for innovative products to show compliance usually with the Irish regulatory system, or at least to give it suitability for market introduction in Ireland. Whereas here we go for enlargement to the entire European Union, you have a possibility as a manufacturer to declare in this ETA or to have declared by an approval body in this ETA all characteristics which are regulated in at least one member state. So you have a real possibility of enlargement, but the document can also be tailored for a manufacturer to the market in which he’s interested. If he says for example "I’m only interested in the UK, the Netherlands, Belgium and France for example," we can include in the ETA only those characteristics of the product for these specific markets."

Asked if a product has been through this process, and has got European Technical Approval, would it then require agrément certification, he says: "The individual agrément certification is a situation which exists today if you don’t have this European Technical Approval. What you would then in that case need, you have one in Ireland and you would have one in UK and one in Germany and eventually have a kind of mutual recognition of them but that is a more actual process. But if you want to conform to get the CE marking and have only one assessment, then you have the possibility of going through this ETA channel."

!["Yes, Agrement certificates are acceptable but [if we see] other test certificates from other recognised bodies, we will consider the materials" - Bob Willams](/img/0214deadcert2.jpg)

"Yes, Agrement certificates are acceptable but [if we see] other test certificates from other recognised bodies, we will consider the materials" - Bob Willams

The other side of the coin

Of course, the argument will be made that European Technical Approval is not directly equivalent to agrément certification.

According to Mr. Caluwaerts of EOTA, there is no limitation on European Technical Approval as far as it falls under the Construction Products Directive. He refers to products, when incorporated in the building, which falls under the six essential requirements which are imposed by that directive on construction works—that is to say safety, mechanical resistance and stability, safety in case of fire, health and the environment, safety in case of use, acoustic performance and energy conservation and thermal insulation issues.

"Any product which fits in these categories that means it would be subject to regulatory requirements in one of the member states—and it’s not governed by a harmonised standard—in that case you have the possibility to have ETAs," he says.

"We have ETAs for innovative thermal insulation materials for example, where not covered by harmonised standards, we have ETAs for special anchor types, and we have ETAs for prefabricated buildings because a prefabricated building is considered by the Construction Products Directive as a product which is brought to the market."

The chief objection raised to ETAs is that they do not take into account the specific climactic conditions in Ireland. However, ETA is designed as a pan-European standard suitable for all EU countries including the likes of Finland which are subject to much harsher conditions and greater precipitation than Ireland as well as countries which likely experience similar levels of rainfall and moisture.

Moreover, some European Union member states, notably Germany are starting to demand that companies opt for ETA and CE marking rather than national certification. This despite the fact that climactic conditions are no more favourable in Northern Germany than in Ireland.

"Well, the point is that the Construction Products Directive which was launched in 1988 and which is the basis for CE marking of construction products, has been implemented in such a way that in practically all the countries with the exception of 4½ , CE marking is mandatory," says Paul Caluwaerts. "It means that you have to have a CE marking once a certain transitional period has elapsed. You have to have CE marking on the basis of a harmonised standard or a European Technical Approval. In 4½ countries—Ireland, UK, Sweden, Finland and Portugal (the half country because they have changed their position recently) CE marking is not considered mandatory.

"So it is the first possibility to prove it, but the national market still allows for national documents such as national agréments. So you have no obligation of manufacturers bringing a product to market in Ireland to have a CE marking, but in other countries you need to do it", says Mr. Caluwaerts.

It does seem unusual in an era of increasing harmonisation of European regulation standards that Ireland does not require CE marking on building products yet in many cases effectively demands strict adherence to its own national standards. The Irish Agrément Board is, after all, a member of EOTA.

Irish standards

The Irish Agrément Board remains adamant that the two standards are not analogous. Séan Balfe, manager of the Irish Agrément Board, says: "European Technical Approval doesn't address certain issues. The big bugbear is durability," pointing to the Department of Finance, Finance Act document HA1. "This document looks for a 60 year durability on main building elements."

According to Mr. Balfe, Irish home-buyers expect the longer durability which he associates with agrément certified products: "Definitely, in continental Europe there is more of a tradition of maintaining buildings," he says. "People in Ireland expect the main building elements to last a lifetime."

Mr. Balfe also says that the Agrément Board does not unduly drag its feet when certifying products: "Average certification time is six to seven months – I don't think that's excessive," he says.

"Some of the building systems, such as timber frame homes, could take longer because there is a lot more to be checked," he says. "If we perceive a technical problem with a product, we investigate it. We don't attempt to frustrate anyone."

One product supplier who does express "profound frustration" at the certification situation in Ireland is Susanne McAllister, Managing Director of insulated concrete formwork company Euromac Building Systems.

"When I started the company I went to visit John Purcell, Sean Balfe's predecessor at the NSAI to ask for advice on certification for the Euromac product in Ireland." she explains. "When he was informed that I was also looking to bring the product to Northern Ireland and the UK, his recommendation was that I follow the advice that he had on the website at the time, to go for "one test, one cert" with the ETA. He outlined that it would be more expensive and take a longer time, but more beneficial in the long term. I remain confident that his advice was sound."

However, having gone through the process of getting ETA certification, McAllister discovered that the use of Euromac in any construction projects involving government tax breaks--and therefore requiring a floor area certificate from the Department of the Environment--was not permitted.

"When I first sought DOE approval for Euromac last year, I was told verbally by Noel Carroll--after months trying to get through to him--that the certificate has been verified but that he was unwilling to give me that verification in writing, suggesting that such a letter could be construed as a letter of comfort, which he was not in the habit of writing.

"He went on to query whether or not I was able to supply him with a suitable render system that had a 60 year guarantee specifically for use on EPS. Within 48 hours I forwarded him documentation on the Maxit product which has ETA specifically for use on EPS and offers a 60-year guarantee, requesting a letter that the Department would approve its use. I have not heard back from him since, which was last summer. Perhaps the content of this article will give the Departments the confidence to accept the ETA at face value.

The energy efficient insulated concrete formwork provided by Euromac Building Systems is just one of the many innovate systems whose uptake has been restricted due to the confused regulatory environment

Mr. Balfe also maintains that the Agrément Board standards guarantee more than just quality control on products, but also their possible implementation in construction in Ireland: "We look 'globally' at new building products being imported—we need to ensure that they'll be used properly and that there will be information [available on how to use a product] and [that] the local skillbase is capable of working with the product.

"80 per cent of product failure is down to installation problems," he says.

In the absence of official harmonised European standards, however, European Technical Approval sets out to offer recognition of product suitability across the EU. Why then, does the insurance situation in Ireland continue to demand further certification such as from the Agrément Board?

According to Homebond's Technical Services Manager Michael O'Grady, Homebond is simply making use of standard Irish building regulations: "The requirements concerning certification of products are laid down in Technical Guidance Document D of the Irish Building Regulations. The guidance given includes a statement that materials must be of a suitable nature and quality in relation to the purpose and conditions of their use and properly mixed or prepared, and applied, used or fixed to perform adequately the functions for which they are intended.

"These requirements can be covered by and specified in appropriate certificates from accredited bodies such as Irish Agrément Board Certificates, British Board of Agrément Certificates, and BRE Wimlas Certification," says Mr. O'Grady.

Mr. O'Grady adds: "If the European Technical Approval certifies that the product complies with the requirements of the Irish Building Regulations in relation to residential construction and includes reference to its use in a system then certainly the certificate could be considered."

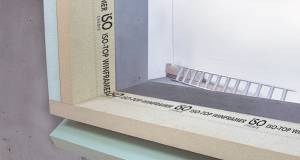

Partial-fill cavity wall construction, shown here with thermal performance severely compromised, is being used in innumerable cases where the application of more innovative systems and products is being obstructed

However, Technical Guidance Document D does not, for example, offer any technical specifications relating to timber frame housing. In fact it is a general document which addresses how materials and systems can be demonstrated to be fit for purpose.

Nevertheless, there is some justification for Homebond's requirement of strict certification. In 2000 concerns were expressed about the suitability of Elliotis plywood being used in Irish buildings. However even this was a somewhat confusing situation. The National Standards Authority of Ireland wrote to the construction industry stating that it had not been demonstrated that that the material was suitable for use in Ireland, particularly in load-bearing situations.

According to a report in the Sunday Business Post on 27 January 2002, (1) the Irish Timber Trade Association made representations to the NSAI, who then sent another letter to the construction industry stating that: "The contents of the [previous] letter may be incorrect."

The Business Post report went on to state: "Householders in whose homes the Brazilian plywood has been used for structural purposes could face uncertainly about insurance cover, mortgages and resale values."

The merits or otherwise of any particular construction material aside, it is reasonable to expect that everyone is in favour of proper certification which ensures product worthiness.

Architect Emer O'Siochru expresses concern that certification could be used in a much more progressive way than it currently is: "I can understand why Ireland has agrément certification to deal with our weather conditions. It also related to the level of building knowledge on-site, so I'm not against it [but] what I do object to is that the Department [of the Environment] could use agrément certification to promote sustainable construction methods.

"If they did that, you could use the system which is a restriction at the moment, to drive sustainable building," she says.

For O'Siochru there is an irony that non-conventional building systems are required to meet higher standards: "We know conventional systems are failing—they have no sustainability," she says.

As a result, O'Siochru favours the development of new and open, sustainable building systems which could be certified by the Irish Agrément Board. "The problem with agrément is that [many of] the new systems are proprietary—the company wants to integrate vertically and capture the market. If in 30 years you need a replacement part, what do you do if the company has gone bust?"

According to O'Siochru, the only way to develop an open 'community owned' construction system is for the government to award an agrément certificate to one. "If the government would just make the money available, it would be very easy to get an open and sustainable system.

"Architects worry too, about adopting new products—our liability lasts for a long time. Architects would very much like an agrément certificate for new methods," she says.

Ultimately, the question is, whether ETA provides sufficient assurance for Irish climactic conditions and the expectations of Irish marketplace. Unfortunately, the answer to this question seems to be a matter of opinion as much as fact.

"This [Irish demand for a 60 year lifespan] is a very strange thing. Legally speaking, Ireland should have brought the 60 year standard to Europe to harmonise on this standard," says Paul Caluwaerts. "I would wonder if Ireland has a testing method which can prove that something has a 60 year lifespan?"

Indeed, ETAs have previously included provisions for specific national and regional climactic conditions: "On the demand of Finland we have included special use categories for very low temperatures," he says.

Caluwaerts continues: "If you go to the European Commission, I think they would see it as a barrier to trade." He also suggests a method by which national certification could be used to enhance European standards: "You come with a product with European Technical Approval and bring a level of performance to a product, saying 'this product can be used in these circumstances'—defining what they are. National approvals could be an additional voluntary standard which you could use to say 'this product is suitable in these circumstances'."

At the present time it seems difficult to ignore the idea that requirement for specific agrément certification unduly slows the appearance on the market of new and innovative building materials and systems which have been developed outside Ireland. If it transpires that concerns about the lifespan of structural materials are correct then such fears would be unfounded. The alternative in this case is to develop a culture in Ireland where active building maintenance becomes the norm.

Conversely, if these concerns turn out to be incorrect, then surely Ireland is missing out on innovate buildings, particularly ones developed with modern materials which are environmentally sound.

If it is the case that agrément certification offers guaranteed compliance to higher standards than are required by the ETA and CE marking, all the better, but that does not seem a reasonable argument for effectively locking out products which are fit for purpose, yet have not achieved agrément certification. Third-party certification such as that offered by the Irish Agrément Board could be used to confer insurance benefits to those products which have it, but at present it seems to mean that those products and systems without it simply can't be used, even if they have passed the tests for European Technical Approval and CE marking.

(1) Brazilian plywood warning by NSA was withdrawn, Pat Leahy, Sunday Business Post, January 27, 2002

- Articles

- Opinion

- Dead Cert

- Technical Certification

- EoTA

- CE

- agrément

- ETA

- innovative

- construction

- sustainable building

Related items

-

Enniscorthy to host ‘make or break’ sustainable building summit

Enniscorthy to host ‘make or break’ sustainable building summit -

BaseTherm liquid floor insulation gets Agrément cert

BaseTherm liquid floor insulation gets Agrément cert -

Towards greener homes — the role of green finance

Towards greener homes — the role of green finance -

Quinn Building Products rebrands as Mannok

Quinn Building Products rebrands as Mannok -

KORE gets NSAI cert for insulated foundation

KORE gets NSAI cert for insulated foundation -

Iso Chemie Winframer gets BBA approval

Iso Chemie Winframer gets BBA approval -

Glavloc awarded Agrément certificate

Glavloc awarded Agrément certificate -

New issue of Passive House Plus free to read

New issue of Passive House Plus free to read -

Passive Sills get BBA cert

Passive Sills get BBA cert -

New digital construction platform launches

New digital construction platform launches -

New Leeds developer goes passive

New Leeds developer goes passive -

Stunning Cork passive house heads list of Isover award winners

Stunning Cork passive house heads list of Isover award winners