Home Truths

Patrick Daly, co-founder of the RiSE (Research in Sustainable Environments) research unit in the DIT has undertaken an in depth study and critique of the current Irish Part L for energy efficiency in dwellings, comparing it in detail to the UK equivalent. The findings raise challenging questions about the Irish standards and methodology and highlight serious shortcomings in comparison to our UK neighbours, permitting substantially higher levels of CO2 emissions from new homes in Ireland than in the UK.

Implementing the EPBD and carbon compliance

Article 4 of the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive (EPBD) requires member states to ensure minimum energy performance requirements for buildings, using a methodology which calculates the overall energy consumption for space heating, cooling, water heating and lighting, as prescribed in Article 3.

Under the directive Ireland and the UK have integrated similar energy calculation methods into their building regulations, and both have introduced limitation of carbon emissions as the ‘principle’ compliance criteria. However on detailed examination of the respective Irish and UK (England/Wales) Part L documents, significant differences emerge in scope and standards especially in relation to the carbon compliance methods engaged and the corresponding benchmarks applied.

The introduction of energy rating into building regulation compliance and in particular the establishment of carbon compliance as the ‘principle compliance criteria’ has added a further level of complexity to the regulations. As such this study required various inter-related and parallel comparisons to be undertaken involving a detailed study of the regulations and standards themselves, the calculation methods employed, and the carbon compliance mechanism engaged, the latter proving to be a key factor in establishing radically different carbon compliance standards in each jurisdiction.

Figure 1 presents a summary of the comparison methodology used comparing the various components directly and integrated via numerous case studies.

The findings show that despite the introduction of DEAP into Part L (May 2006) of the Irish building regulations, there has been no improvement in standards despite what would have been a consequential improvement in standards via a broadening in scope from a fabric heat loss compliance base to incorporating overall energy consumption and carbon output. How a mechanism was devised to avoid such a widening of scope and consequential improvement in standards was a core finding of the study.

Comparison model showing inter-relationships of regulatory components and integration in various case studies © Patrick Daly

The study also highlighted that the Irish Part L is significantly behind the UK equivalent including a major difference in relation to the setting of limitation of carbon emissions, (which both jurisdictions refer to as the ‘principle compliance criteria’), with the UK implementing a more robust compliance benchmark and applying a 20% improvement factor.

Irish Part L falling significantly behind the UK

A detailed comparative analysis of the Irish and UK Part L documents showed a considerable difference in structure, scope and standards, with the UK Part L significantly ahead of the Irish equivalent.

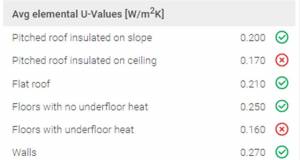

These include the UK Part L having higher minimum boiler efficiencies, minimum air permeability levels, mandatory air pressure testing, guidance and standards covering a broadening spectrum of technologies, including heat recovery ventilation, and a move to include performance criteria into compliance requirements as opposed to solely mandating design standards.

In addition the UK regulations have undertaken a radical review and update to Part F (ventilation), which correlates with the importance of ventilation control in relation to energy in dwellings and to the growing range of systems and approaches emerging in energy efficient house design and practice.

Figure 2 shows a summary comparison of both Part Ls highlighting principle differences in scope in blue and in standards in red.

A comparison model showing structure, scope (blue) and standard differences (Red) between the Irish and UK Part L © Patrick Daly

DEAP and SAP

DEAP as a calculation method is significantly based on SAP 2005 and is more of a modified or adapted version than an alternative method. However it does have significant calculation differences mainly in the space and water heating fields, with space heating in DEAP being based upon a different calculation methodology, integrating the concept of thermal mass as a factor via an allowance for the internal heat capacity (IHC), and using different (Dublin) climate data. Water heating differences derive from a difference in standard occupancy and contribute to the overall calculation difference which in the example study is in the 9% region in delivered energy terms.

In addition to the calculation difference there are important differences from the building control context and from differences in definition and methodology. Notable among these is the difference in interpretation of Part F background ventilation.

Given the complications of neutralising a diverse range of differences between the calculation methods the case study comparisons were based on comparing Irish minimal compliance specifications with the TER (target carbon dioxide emission rate), the UK minimal compliance specification, in DEAP.

Importantly the study showed that the critical issue in relation to differences in compliance was regulatory standards and in particular the carbon compliance mechanism as opposed to differences in calculation method in DEAP and SAP.

The reference house carbon compliance mechanisms – a comparison

In addition to the UK establishing a clear 20% carbon improvement factor, there are critical differences between the two jurisdictions in the setting of reference values for the ‘notional’ or ‘reference’ house against which the carbon output of the ‘actual’ design is compared and this is shown to be the most radical and divergent aspect of the two methodologies.

While there are marginal differences in the carbon ‘reference’ values for fabric and ventilation fields and specification, the critical difference occurs in that the Irish carbon reference values for most of the space and water heating fields are taken from the ‘as actual’ design and not from the ‘reference’ specification, except in the case where renewables meet all of the space and or water heating demand. Notably the Irish MPCDER (maximum permissable carbon dioxide emission rate) reference specification for boiler efficiency is 78% ‘or lower’, which means that the boiler efficiency is neutralised for lower values, while a compliance benefit is maintained if above. In addition there are no ‘reference’ values for fuel type, systems controls and secondary heating.

The implication of this is that there is no ‘fixed’ reference house carbon benchmark for the Irish Part L (for non renewables), and the Irish MPCDER value can vary accordingly and facilitates compliance for a range of low efficiency systems and fuels high in primary energy and carbon, which can be specified without any compensatory or trade off measures being required.

The reference house specification and mechanism adopted in Ireland has in effect neutralised key aspects of energy and carbon compliance and reduced Articles 3 & 4 of the directive back to a benchmark for fabric and ventilation losses only which has significant impacts in both energy and carbon compliance terms. As such the Irish Part L carbon benchmark could be described as a quasi or partial benchmark.

Comparing Irish and UK carbon compliance standards

DEAP calculations were undertaken for a range of Irish minimal compliant case studies based on various compliant fuel, efficiency and systems specifications and compared against the UK TER carbon reference values in DEAP, the results of which are indicated in figure 3. These show the fluidity of the Irish carbon ‘benchmark’, compared to the UK (TER with 20% improvement factor), allowing a diverse range of permissible carbon values and critically facilitating compliance for a range of high carbon fuels and low efficiency systems.

The case studies indicate that for a typical three bed-room semi detached house (based on the Part L documentation example), Irish minimal Part L carbon compliance can vary significantly (133% based on examples) and can be typically 27% to 70% above the UK equivalent TER threshold for typical gas and oil automated central heating systems but can be as high as 200% above for certain fuels and low efficiency systems, all of which would be compliant in Ireland and require no trade off or compensation.

This highlights that Irish building regulation standards are now significantly below the UK standards for England and Wales and would in general be below that of Northern Ireland and Scotland, subject to fuel type, as they have similar thresholds to England and Wales, with Scotland having a range of reference specifications and Northern Ireland having two.

Figure 3 shows delivered energy (yellow) and primary energy (blue) and carbon emissions (green) for a range of fuel and efficiency types based on an example Irish minimal Part L compliant three bedroom semi detached house. All examples are carbon compliant with the MPCDER equal to or above the CDER. MPCDER limits vary by 133%, with different standards applied to the renewable example (wood pellet). The UK TER reference specification is shown on the right hand side. The red line indicates the UK 20% carbon improvement factor off the TER level. This level is fixed subject to building geometry only. The Irish compliant specifications’ percentage over the UK equivalent threshold are indicated in red and expressed as percentages.

© Patrick Daly

Analysis and comment

Despite the sophistication of the DEAP tool it is clear that the setting of reference values by the DoEHLG in the Irish Part L has in effect reduced the scope of carbon compliance from an overall energy/carbon benchmark to a fabric and ventilation benchmark principally, with boiler efficiency functioning in terms of trade off and carbon benefit if over 78%, but no carbon compliance negative if lower, (subject to other non Part L legislative efficiency minimums). As such, surely the concept of carbon compliance being the ‘principle’ compliance criteria is called into question.

The Irish Part L MPCDER specifies fixed carbon reference values for fabric and ventilation heat losses primarily and a partial benchmark for space heating efficiency at 78% or lower. The ‘or lower’ reference here is pivotal as it allows the MPCDER benchmark value to vary – or in other words, increase – with the specification of lower efficiency boilers.

The only area that comprehensive and fixed MPCDER reference values are applied is in relation to renewable energy, for which, if space and or water heating are met by a renewable source, the MPCDER has an additional range of reference values incorporated, approximating to the UK TER values. As such renewable energies are set more stringent carbon limits.

Avoiding improved standards

Given that there was a major change in compliance methodology via the integration of Article 3 and 4 of the EPBD and noting the change to limitation of carbon emissions as the principle compliance criteria, there was surely opportunity to either introduce improvements over previous standards, as the UK did or to at least allow or facilitate a ‘consequential’ improvement in standards and scope resulting from the introduction of an overall energy/carbon method into the regulations.

However it is evident that the setting of the MPCDER ‘reference house’ values avoided any such consequential impact of Articles 3 and 4 of the directive, specifically excluding energy or carbon content of fuels and system efficiencies, which therefore ensured no energy or carbon improvement over the old 2002/5 fabric heat loss standards. In effect the potential impact of Article 3 and 4, if it was intended to ensure that member states set standards on overall energy consumption, was neutralised.

It is important to realise that the structure and design of the reference values is pivotal to the standard and scope of carbon compliance and is key to the widening gulf between the Irish and UK standards. Given the impacts of this, the reasons for the strategy undertaken by the DoEHLG in this regard should be questioned and challenged.

Compliance negatives

The MPCDER ‘partial’ reference values means that there is no compliance benefit to improving on fuel type or heating system controls or hot water insulation levels. This has clear impacts in terms of take up of energy efficient and low primary energy and low carbon technologies and is not in harmony with general government and EU policy and targets in relation to promoting these sustainable technologies.

Conversely the partial MPCDER referencing also limits designers in the range and scope of options in achieving compliance, to ventilation, fabric insulation and boiler efficiencies primarily.

Facilitating fossil fuels

Importantly the MPCDER partial referencing facilitates compliance for a range of high primary energy fuels, high carbon content fuels and low efficiency systems, which may otherwise be non compliant or have to be compensated for. Again this seems to counter EU and stated government policy.

Renewables – dual standards

The Irish MPCDER mechanism ensures renewable energies are given a stricter compliance reference benchmark with full reference values for efficiencies in space and water heating controls and insulation. As such they are not only set a more stringent compliance benchmark but are denied any compliance advantage over more primary and carbon intensive fuels despite their carbon efficiencies and as such their specification is not encouraged by the approach taken.

Secondary heating

In relation to secondary heating there are no compliance penalties to avoid low efficiency and poor fuel type secondary heating systems in the Irish method, yet variations in secondary heating and fuel type can have a significant impact on overall energy efficiency.

Technology dumping

As Ireland’s standards in relation to energy efficiency fall behind standards in our European and nearest neighbouring states there is a risk of market dynamics forcing ‘technology dumping’ into the Irish market. This could be taking place across a range of products and systems but is especially apparent in relation to heating systems. For example, given that our minimum boiler efficiencies are significantly below our UK neighbour it is not unreasonable to suspect that boilers now no longer marketable in the UK (or other EU markets), are being dumped into the ‘lower’ regulatory market of Ireland.

UK future trends

Our attention should not only be on the significant current disparity between Irish and UK standards but also on the rapidly changing short-term landscape of building regulation standards in the UK with developments on the horizon to achieve zero carbon housing by 2016 and even as early as 2011, according to the Welsh National Assembly.

In additional the UK have also signalled an intention to expand the scope of building regulation compliance for both energy and environmental impacts via the incorporation of the Code for Sustainable Homes into their building regulations in 2008, which presents further challenges to the current and proposed improved Irish Part L despite an aspiration to improve the Irish building regulations Part L in 2008 by 40%.

EU / government policy

Given the commitments and targets set within various EU and Irish government policy papers regarding carbon reduction and promotion of renewables, one could question if the recent revision to Irish Part L was in harmony with these objectives. Certainly the specific neutralising of any impact of Article 3 and 4 of the directive via an expanded scope, which ipso facto would have meant improvements in standards, is open to criticism.

Concluding comments

This study has shown that the recent May 2006 update to the Irish Part L included no improvement in standards over the 2002/5 Part L and the introduction of a quasi carbon compliance benchmarking method has neutralised any positive compliance impact of implementing article 3 and 4 of the directive, with clear energy and carbon impacts.

The consequences of the adopted methodology – namely that it facilitates high carbon fuels and low efficiency systems, and in effect established a dual standard with a more stringent benchmarking method for renewables – are clear and the comparison to the UK standards has shown the impact of the DoEHLG strategy; typical minimal compliant housing in Ireland can be 30% to 70% worse than the UK standards and up to even 200% for some fuels and systems, as the example case studies demonstrate.

Importantly the ‘variable’ MPCDER reference mechanism calls into question the concept of percentage improvement targets and renders the 40% improvement referred to in recent government papers as unquantifiable in the context of current Part L compliance which can vary itself by some 130%. For example a 40% reduction based on a reference to oil at 78% efficiency is significantly less than 40% off gas at the same efficiency. 40% could in fact be 20% depending on what you measure off.

The study has shown that the current Irish Part L is sub-standard, out of date and out of sink with emerging developments. In particular its claim to have established limitation of carbon emissions as the principle compliance criteria is certainly to be questioned.

Given that Part L is currently under review, let’s hope that we get a radically improved and robust document that is in full accord with the spirit and intent of the directive, which was surely to improve and widen the scope of regulatory standards, and more importantly that we move to a position where our regulatory standards on energy and environmental impacts from buildings are at the forefront of sustainability in buildings and comparable to that of the UK and other leading EU states.

This article and graphs contained within are copyright of Patrick Daly and not to be used copied or transmitted without express written permission of author. The author has taken reasonable measures to ensure accuracy of the study and accepts no liability for information contained therein.

- Articles

- Obstacles to Sustainable Building

- Home Truths

- building regulations

- part l

- Energy Performance of Buildings Directive

- carbon compliance

- maximum permissable carbon dioxide emission rate

- MPCDER

- DEAP

Related items

-

Scotland to accept passive house as regs compliant

-

Embodied carbon & zero emission targets adopted in new EPBD

Embodied carbon & zero emission targets adopted in new EPBD -

EU votes through EPBD recast

-

Disappointment at new building energy standards

-

When is an A-rated home really A-rated?

When is an A-rated home really A-rated? -

Grant launches online learning academy

Grant launches online learning academy -

Northern Ireland claims 2012 regs meet NZEB

Northern Ireland claims 2012 regs meet NZEB -

Wales to introduce building regulation on overheating

Wales to introduce building regulation on overheating -

Software errors create false NZEB compliance picture

Software errors create false NZEB compliance picture -

WWHR an easy & costeffective route to Part L compliance — Showersave

WWHR an easy & costeffective route to Part L compliance — Showersave -

How will today’s buildings perform tomorrow?

How will today’s buildings perform tomorrow? -

'Achieving NZEB' event in Cork this Thursday

'Achieving NZEB' event in Cork this Thursday