- Renewable Energy

- Posted

New Power Generation

Richard Douthwaite explains how inadequate conventional energy generation is and reveals the potential that combined heat and power & energy service companies can offer.

Space heating using electricity is monstrously wasteful and inefficient. Moneypoint power station, Ireland's largest, converts only a third of the energy in the coal it burns into electricity and then 14 % of that is wasted in line losses as the power makes its way to the customer. Gas-fired power stations perform rather better. Huntstown turns 55% of the energy in the gas it burns into electricity but, thanks to the line losses, only 47% of the energy from the gas actually gets delivered.

All told, 20% of all the energy in the fuels burned in Ireland gets wasted being turned into electricity. That amounted to the equivalent of 3 million tonnes of oil in 2004. Such massive inefficiency was acceptable in an era of very cheap fuel but that's no longer the case. Electricity is a premium fuel, which needs to be reserved for the jobs it does best, such as lighting, powering motors and running electronic equipment. The bulk heating of water and air needs to be done in some other way.

Getting the heat from a combined heat and power system is one approach. If fuel is burned in a good conventional boiler, 85% of its energy can be turned into heat and only 15% is lost to the atmosphere. However, if that fuel were to be burned in a CHP plant instead, the losses would stay at 15% but perhaps 25% of the fuel's energy could be turned into electricity, which has a much higher market value than just common-or-garden heat. This makes CHP not only an energy-efficient approach to heating but also a cost effective one.

Click Image for Larger view

Illustration 1: Why CHP is attractive. The first arrow shows what happens in the present Irish electricity system – on average 63% of the fuels' energy is wasted by the power stations and then more is lost on the way to the consumer. The second arrow shows what would happen if those fuels were used just to generate heat – the losses would fall to 15%. The third arrow shows the outcome if both heat and electricity were generated. The losses would stay at 15% but up to 25% of the energy could get turned into a form more valuable than heat; electricity. And if that electricity was used on site, the waste on the way to the consumer would be avoided.

CHP can be used on a domestic scale. A micro-CHP plant can be installed in an individual house to replace the gas central heating boiler and provide the majority of the family's electricity needs in addition to heat and hot water. Powergen, a major British electricity and gas supplier, expects that one day, micro CHP will provide 20% of Britain's electricity generating capacity, more than is provided at present by nuclear power.

Moneypoint Power Station

The company has committed itself to installing 80,000 Whispergen units by 2010 and will purchase any surplus electricity from its customers at 3p per unit, rather less than the 12p price it charges for a unit at present. This is very good business for the company, particularly as it expects that its customers will be producing power at times of peak demand when its costs are highest. Nevertheless, it expects that its Whispergen customers will get reduced bills.

But perhaps they won't . The results from trials recently carried out by the Carbon Trust, a British Government-funded company charged with finding ways to cut carbon emissions, have proved disappointing. The study involved forty units, including those using Stirling engines like the Whispergen, organic Rankine cycle machines, fuel cells and internal combustion engines. It found that the overall emissions reductions (and hence the energy saved) were nowhere near as large as expected.

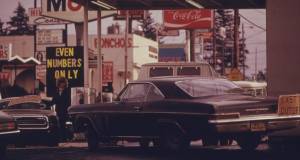

Huntstown Power Station turns 55% of the energy in the gas it burns into electricity and then 14% of that is wasted in line losses as the power makes it way to the consumer

One reason for this was that a micro-CHP unit, particularly one with a Stirling engine, must reach a fairly high operating temperature before it can generate electricity. During its warm-up period it provides some heat to the building but no electricity is generated. Naturally, warming the unit to operating temperature absorbs energy. If the unit was only started once a day and then ran steadily for many hours the impact of this would be very small. However, in many properties, heat demand is intermittent and the repeated warm-ups absorb a significant amount of energy which is not re-released in a useful way. This reduces efficiency.

Household scale CHP might therefore turn out to be a blind alley. Providing energy heat and electricity for a number of buildings should enable the plant to run continuously and thus be more efficient. Moreover, it might be cheaper to install one large plant rather than forty or fifty small ones. Certainly, several developers in Ireland are thinking this way, often in response to the increasing number of local area development plans like those in Fingal which require 30% of the energy used for space heating and hot water to come from renewable sources. Although developers could meet this target using solar collectors, they would have the expense of putting in back-up systems too whereas, with CHP, one system can do the whole job.

What's more, a CHP system has the potential to become a nice little earner for them as they can sell the electricity they generate to the occupants of the properties at the full commercial rate. They can, that is, if the can get approval from the Commission for Energy Regulation to install a direct wire supply system, an approval which the Commission is expected to be extremely reluctant to give despite the fact that it is obliged to do so under the 2003 European Directive setting out the rules for the internal market in electricity. The only stipulation in the Directive that the Commission is required to observe is to ensure that anyone obtaining electricity through a direct wire has the option of buying their power from someone else.

Early in 2003, the architectural firm O'Mahony Pike proposed that a natural-gas fired fuel cell with a 250 kW (electrical) capacity should be used to supply electricity by direct line to 200 houses in Adamstown, the new town being built outside Dublin. The cell would have turned 55% of the energy in the gas to electricity, 32% would have been heat for a district heating system and only 13% would have been wasted.

O'Mahony Pike also looked at a more conventional approach, using the gas to power an internal combustion engine and having that turn a generator. This would have turned only 30% of the gas energy into electricity and given 45% as heat, with 25% as waste. Since it doesn't take a lot of heat to warm a well-insulated house – and O'Mahony Pike worked hard to ensure the Adamstown houses were good in that respect - the fuel cell option made much more sense as it produced the more useful, higher value electricity. O'Mahony Pike's proposal was not taken up at the time but the partnership is optimistic that a similar scheme will be tried in Adamstown before too long.

Adamstown Castle.

At least three CHP projects involving Paraic Davis of Davis Associates mechanical and electrical engineers have been hamstrung or restricted by the ESB. One of these is at Eblana Avenue, Dun Laoghaire, where 70 apartments, 1,000 square meters of offices, the same area of retail space and two floors or car parking are to be built. It was hoped that they would all be heated from a gas-fired CHP plant which would also meet the electrical base-load through a direct-line system. However, because of the difficulties the ESB could be expected to cause if this plan went ahead, the CHP unit will be much smaller. “It will just be big enough to provide the baseload in those parts of the building occupied by the landlord, like the lighting in the car park, which is all that we can be confident we can provide given the barren Irish interpretation of the EU Directive” Davis says. As a result, the unit will produce too little heat for all the buildings. The shortfall is likely to be made up with heat from a wood pellet fired boiler and there is even a risk that the CHP element will not go ahead.

Another project in which the CHP element was cut back is in Ballymun. The original plan was to use CHP to provide heat and electricity to the new swimming pool and leisure centre, the civic offices and the Arts Centre. “This would have been an ideal arrangement because we could have met the electrical demand and used the swimming pool as a dump for any surplus heat, “ Davis says. Unfortunately, the swimming pool is across a road from the other two buildings and this gave the ESB the excuse to threaten that they would only supply one of the buildings if the direct line system was installed across the road. “They said that they would make life as difficult as possible for us, so the council backed off” Davis says. The upshot was that only the swimming pool will have CHP power.

“Because of ESB opposition, we can't even connect up the photovoltaic panels that are being fitted to the 39 apartments in the Emerald Housing development in Ballymun, despite the fact that this is a demonstration project with a €750,000 SEI grant” Davis says. “The Regulator seems to back the ESB's position. We've asked for a three-way meeting but have so far been unable to get one set up.”

These issues need to be sorted out. When they are, it would obviously be better that, rather than having individual developers supplying their projects with heat and power on a piecemeal basis and leaving existing properties to be supplied conventionally, whole communities set up their own Energy Service Companies (ESCOs) and developed their local renewable energy sources for everyone living in their areas. Bantry town council is already thinking in these terms and is exploring whether it can lease the whole of the distribution grid downstream of Eirgrid's sub-station in the town and use it to supply the district with wind and CHP electricity generated locally, topping this up from the grid when required. The heat from the CHP plant could go to the hospital, a new hotel and other buildings in the town. These could include a fish processing plant where the heat would replace the electricity now used to cool the cold stores.

How the electricity price paid by the consumer breaks down. By using a direct line system and eliminating the transmission, distribution and supply components of the price, local electricity generators should be able to out-compete suppliers like the ESB. Source: Future Energy Policy in Ireland, Irish Academy of Engineering, 2006.

If this plan goes ahead, Bantry would be using the model adopted by Europe's most progressive renewable energy countries where most towns already have their own municipally -owned heat and light companies. For example, in Vaxjo, a city the size of Limerick to the southwest of Stockholm, the municipal council decided in 1996 that the city's greenhouse emissions would be cut in half by 2010 and that the longer-term goal was to make it entirely fossil fuel free. It opened a central biomass-fired CHP plant in 1997 which brought about a major emissions reduction and smaller plants were then opened in the outlying villages.

By 2004, the latest year for which data is available, 84.7% of all the heating in the municipality was by biomass. However, reducing the emissions from transport was not going nearly so well, although until last year the city gave grants to people wishing to buy electric, ethanol or hybrid vehicles. “We must have more of those than anywhere else in Sweden, but even so, it's hard to get vehicle emissions down” Sarah Nilsson, the city's sustainable development manager told me in August. “As a result, we've only been able to cut our total emissions by 25%.”

- Articles

- renewable energy

- NEW POWER GENERATION

- Carbon Trust

- Richard Douthwaite

- huntstown

- moneypoint

- chp

- solar collectors

- commission for energy regulation

- adamstown

Related items

-

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries -

The first oil crisis

The first oil crisis -

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March -

Energywise Ireland open new renewables showroom

Energywise Ireland open new renewables showroom -

Together in Electric Dreams

Together in Electric Dreams -

Passive House Plus back issues now freely available online

Passive House Plus back issues now freely available online -

Ireland's 1st hemp-built passive house

Ireland's 1st hemp-built passive house -

Striking London building catches the eye as well as the sun

Striking London building catches the eye as well as the sun -

Passive House Institute launches new cert categories

Passive House Institute launches new cert categories -

Passive house: an alternative method of meeting Part L?

Passive house: an alternative method of meeting Part L? -

Do Ireland’s energy efficiency regulations penalise energy efficiency?

Do Ireland’s energy efficiency regulations penalise energy efficiency? -

Ireland’s energy roadmap — have your say

Ireland’s energy roadmap — have your say