- Renewable Energy

- Posted

Smart Move

The introduction of smart metering later this year presents a great opportunity to engage Irish people en masse into substantially reducing their energy consumption, simply by showing them how much electricity they’re consuming, and how much the cost varies at different times of the day. However, as Richard Douthwaite warns, there is a real risk that smart metering may come in a form that benefits the electricity companies and not the end-user.

A remarkable change of attitude has taken place over the past few months within Ireland's electricity supply system. The evidence? It will soon be possible for almost anyone to sell small amounts of electricity to the grid at a reasonable price.

“In comparison with 18 months ago, it's quite easy now to get permission to connect a generator with up to 500kW capacity to the grid” says John Quinn of Surface Power Technologies in Mayo. This is a far cry from the situation in which the Camphill Community in Ballytobin, Co. Kilkenny, had to burn off surplus gas from its biogas digester for six years before it received permission to use the gas to power a generator and sell the electricity into the grid. “The Commission for Energy Regulation and the planning section of the Department of the Environment deserve a pat on the back for what they have achieved,” Quinn adds. “They've put us ahead of a lot of European countries.”

Although many potential combined heat and power (CHP) projects were stillborn in the past because the ESB would not take the power at a decent – or any – price, developers with suitable projects today should explore the possibilities again. Only those with plans for wind turbines over 500kW will still face difficulties. This is because so many people want to invest in wind farms that a 4,000MW queue has built up and applications are being processed in batches according to where the farms are to be sited and how long the application has been in. “Applications for 2,600MW have been in so long that the planning permissions for the wind farm sites will lapse shortly unless construction starts soon” says Peter Keavney of Galway Energy Agency, who is a council member of the Irish Wind Energy Association.

Even if some applications lapse because planning consents are not renewed, the backlog could last for many years because existing wind farms have enough capacity to meet over 40% of the country's needs in the middle of the night if the wind is blowing strongly and this forces the gas and coal-fired generators to cut their output.

In theory, that's just what should happen because it means that expensive fuel doesn't need to be used and greenhouse emissions are cut. In practice, however, having wind power available at a time of low electricity demand is just a nuisance because the combined-cycle gas-fired generating capacity that supplies almost half of the country's power only works efficiently when running at its design output and it takes time and wastes fuel to move its output up and down. The same is true, though to a lesser degree, for the ESB's coal-burning station at Moneypoint and the operators of similar plants in Britain have even been known to pay to have their power taken by the grid in the middle of the night so as to avoid the cost and trouble of shutting their plants down only to have to get them on full output three or four hours later.

The trouble is that Ireland's fossil-fuelled power stations are designed for continuous base-load operation and are thus unsuited for allowing much wind electricity on to the grid. This could be solved if some open-cycle gas-fired “peaking” power plants were installed. These are less energy efficient for continuous use than their combined-cycle cousins but can be brought on line quickly whenever they are required. “It's a scandal that the recent combined cycle power stations were given a derogation from the grid rules for plant responsiveness just when more responsiveness was required!” says Larry Staudt of the Centre for Renewable Energy at Dundalk IT.

The All-Island Market for Electricity (AIME) which came into operation on November 1 should provide operators with the financial incentive to install some peaking plants. The new market works by giving the big generating companies, North and South, the choice of whether they want to be a price maker or a price taker. If a firm opts for the price making role, it tells the grid operator each day the price and quantity of the electricity it can supply for each half-hourly period in the following 24 hours. The grid operator then orders power from the cheapest suppliers to cover the expected demand, with each supplier being paid the price demanded by the most expensive operator chosen.

Price takers, on the other hand, just tell the grid operator how much power they will have available and get whatever price for each half-hourly period the price-makers are being paid. Small producers – those under 10MW – don't have to participate in this market directly if they choose not to do so. They can simply contract to sell their power to a company that is involved.

Because the demand for power can double over the course of a day, from the night-time trough to the early-evening peak, (See Illustration 1) the price at which the power supply companies buy their electricity from the AIME pool can triple within the space of a few hours as Illustration 2 shows. It would be during the high-price periods that the “peaking” power units would come on line.

Since electricity supply companies don't like selling power for less than it costs them to buy, they are keen to be able to change the prices they charge their customers at least every half hour. This would ensure that they always got a decent margin on the price they paid to buy from the pool. But frequent changes in the price of power are impossible with existing electricity meters which only record the amount of power taken but not the time of day. All the country's meters therefore need to be changed and, in deference to the companies' wishes, the 2007 Programme for Government says that it will “Ensure that the ESB installs a new smart electronic meter in every home in the country which will allow people to reduce their bills by cutting back on unnecessary use of electricity.” For “Unnecessary” read “ill-timed”.

Early in November, energy minister Eamon Ryan announced that 25,000 smart meters were to be installed in a pilot programme beginning in the second quarter of 2008 and that all existing meters were to be replaced over the next five years. While manufacturers have been invited to tender to supply the trial batch of meters, estimated to be worth about e10m., no detailed specification for these has been published. All the tender invitation says is that “The meters will be required to include features such as interval and register reading, import/export measurement capability, remote reconfiguration, integrated switch which can be remotely operated, local area network capability and provision of a gateway to the home area network. A compatible in-home display unit for trialing in the pilot would also be desirable.”

Larry Staudt stands in front of the wind turbine at DKIT’s Centre for Renewable Energy

Ireland will have to take whatever meters are in current production for the the pilot programme as that starts so soon. However, since re-metering the whole country will cost perhaps e600 million, not only is getting the right design very important, but the market is big enough for firms to produce what we want. Such meters may not be available yet since only a few parts of the world – Italy, Sweden, California, the Netherlands, Ontario, and Australia – have installed smart meters on any scale and none of those which have possess Ireland's wind energy potential. A Bristol smart meter manufacturer, Horstmann, was unable to tell me of any firm which makes meters with a load management system that the domestic consumer could control.

Apart from the import/export capability, which will allow anyone with their own generating equipment to sell power to the grid, and the “desirable” in-home display unit, all the features mentioned in the invitation to tender benefit the electricity supplier rather than the customer. For example, besides getting a price that always covers their costs, suppliers will no longer have to send out meter readers and will be able to disconnect their customers, or limit the amount of power they can draw, at will. The new meters will also be able to report on the quality of the supply, the state of the network and whether the customer has attached unapproved generating equipment. The suppliers' cash-flow will improve too as they will be able to require customers to pay in advance by topping up their meters in the way they top-up their mobile phones.

What the customer may not get is a way to respond automatically to changes in the price of power. The in-home display unit will tell him or her the price of electricity at any given moment but it could be left to them to respond to that information by going round the house turning heaters and appliances on and off. This won't work well even in the most conscientious household as the family will be either absent or asleep for much of the week.

What's needed is a computer-based programmable system so that, if the wind blows strongly and the power falls below a price-point the customer has pre-set, the immersion heater or the washing machine is automatically turned on, the chest-freezer is given a blast, the ground-source heat pump starts to run and the electric car's battery goes on charge. Equally, if ever the price of power rose over a certain level, only lights and electronic equipment would stay on. Such a system would not only lop the tops off the peaks in electricity demand and fill in most of the troughs but would provide a market for increasing amounts of wind-electricity which Ireland will otherwise have in surplus supply.

Smart meters are essential for achieving another goal in the Programme for Government: “the introduction of net metering to allow consumers to sell electricity back into the grid from any renewable power supplies they have.” I understand the plan is that anyone feeding electricity into the grid through their meter will be paid whatever price they would have to pay at that moment if they were drawing power out. “The problem with old-style net metering was that someone could draw power from the grid at a peak period and then offset this by putting power back at a time of low demand” John Quinn comments. “That could even increase Ireland's carbon emissions.”

The new form of net metering could make investing in a CHP installation really attractive if it could be run to produce a lot of electricity for export at times of peak demand. Indeed, it might be more profitable to run it, or even a standby diesel generator, so as to enable a factory or a large office block to become independent of the grid at peak times. This is because under the All-Island Market rules, firms, or groups of firms, with a power demand of 4MW or more can be paid for ceasing to draw electricity whenever it suits the grid operator to ask them to do so. Any firm doing this would not only save the difference between producing its own power and buying it in at the top rate, but it would also be paid a premium as well.

Jerry Sweeney of Synergy Module is working with Irish Energy Management Ltd to assemble a group of firms prepared to shed load at times of heavy electricity demand. “It's called Demand Side Bidding. The idea is that the firms tell Synergy Module the price at which they are prepared to reduce load and the amount of load they can cut at that price. Synergy Module aggregates this information into a collective bid on behalf of enough firms to meet the 4MW minimum power demand requirement. When the demand for electricity threatens to exceed the supply, AIME will tell Synergy Module to reduce demand and we'll do so using the direct electronic controls we'll have over our members' loads.”

The new electricity market makes it possible – but not easy - for small electricity generators to become electricity suppliers. One man who has done so is Dan Twomey of Banteer, Co. Cork, who developed a 70kW waterpower site in Cork city in 2004 and sells the power produced there to Cork City Council for 10% less than it would have to pay the ESB. “I've got two more turbines waiting to go in and that will give me 170kW capacity” he says.

Under the new arrangements he has to sell the power he produces into the All-Island Market pool, in which he's a registered participant. He's a price-taker and is paid for whatever he supplies at the relevant half-hourly prices as recorded by a step-meter in his turbine house. He supplies 100 ordinary meters on various Cork City Council premises. These record the power they draw from the grid in the normal way and are read by the Meter Registration System Operator (MRSO), a “ringfenced” part of ESB Networks, which lets him know what the council has consumed and also tells the All-Island Market pool what it should bill him. “I get the AIME bill every Friday and have to pay it by the following Wednesday” he says. “I have to pay the difference between the amount of electricity I've supplied and the amount it is estimated my customer has used.” An adjustment is made when the Council's meters are actually read.

In addition to the price at which he buys the additional power, he pays for the use of the distribution grid to carry what he buys to his customer. And, even though none of his electricity would go through the transmissions grid's high-voltage lines if the electrons he put into the system actually found their way to his customer, he also has to pay e800 a month for the use of the transmission system. “They tell me I've got to pay because I need the transmission grid to excite my generator” he says. On top of this, he pays a capacity charge because he's drawing more electricity from the system than he puts in. If he was just generating power and not supplying it, he would be paid a capacity charge simply for providing the system with a source of power it could draw upon if ever it was required. “Even with the two new turbines, I'm still going to have to buy in electricity each summer because I have an agreement with the Fisheries Board that I close down in July and August” he says.

“It was quite a business setting it all up” he adds, “but I felt I had to do it because I've been installing waterpower systems for 25 years and I wanted to be able to tell my customers what they should do if they ever wished to become a licensed supplier.”

John Fingleton of Fingleton, White and Co. of Portlaoise, has a lot of experience in designing and installing CHP systems. He thinks that it's not really worthwhile installing a district heating system if the houses involved are well insulated. “The insulation spoils the economics” he says. A group of buildings with a high heat demand or a manufacturing plant that needs process heat is a different matter and it could well be worth installing a CHP plant and selling its electricity to the grid. “There's no difficulty doing it and, if you are using biomass as your source of heat, you can sell your electricity at a fixed price of 7.2 cents/kWh if you wish, which includes the 15% REFIT premium.”

Since this is scarcely generous - it is around half the gross price Twomey receives - Fingleton would like to see CHP producers get a better deal, as they may do when net metering comes into operation. “If your maximum power export capacity is greater than the amount of power you would ever import, the standing charges on your electricity bill are reduced below the level you would pay if you simply bought your power” he says. “But CHP generators don't get paid for strengthening the grid if the supply is weak in their area. They also don't get paid for the capacity they add to the grid which other generators receive.”

Peter Keavney also thinks that there are good prospects for “auto-producers” who generate enough power to meet the base loads of their factories and sell any surplus to the grid. He is hoping to install a 750kW wind turbine at Galway's new sewage treatment works at Mutton Island to do this. “It will meet 56% of the plant's electricity requirement and save e250,000 a year” he says. “Because we can't supply more than 499kW to the grid, we'll have to put a braking mechanism on the turbine for the times when there's a strong wind and the plant doesn't need a lot of power.”

The government hopes that the combined effect of smart meters and varying the price paid to generators according to the level of demand will be to make electricity production more fossil energy efficient. That's obviously desirable but price differentials cannot control the amount of electricity that will be produced at any moment by the wind. Unless something is done, electricity from this source is going to be an embarrassment to the system at least until the projected trans-European grid linking wind farms from the west coast of Ireland through to the coast of Finland is completed, and it can be exported. And perhaps even then.

What Ireland therefore needs is a smart metering system that encourages consumers to find uses for electricity when a strong wind is blowing and its price falls really low. If Eamon Ryan responded to the electricity suppliers' demands by pushing ahead with the installation of smart meters that didn't make it easy for consumers to take advantage of very low power prices whenever they occurred, he would be making a big mistake. His rush for results would inhibit the development of, amongst other things, wind farms, domestic heat storage systems such as heat pumps combined with underfloor heating, and the use of electric cars.

The Minister has assured ConstructIreland that he has no intention of making this mistake, even though sufficiently advanced smart meters may not be in production yet. “We're pushing the boundaries here” he said, “but I do want it to be possible for 100,000 fridge-freezers to be turned off at 5.30 each evening.”

The unresolved question, though, is who will turn them off. Will it be 100,000 electricity customers who have individually set their smart meters to do so whenever a particular power-price kicks in? Or will it be the electricity supply companies who will send the cut-off signal to their customers' meters?

The uncertainty exists because it has still not been decided whether the price to be paid by domestic electricity customers should vary by the half hour or whether those customers who agree to allow their electricity suppliers to turn their appliances on and off remotely should pay a lower flat price for all their power than those who don't. This decision about who is to be in control is absolutely crucial. It would be a massive mistake if flat power prices were to stay.

- Articles

- renewable energy

- Smart Move

- smart metering

- douthwaite

- Economist

- energy consumption

- Reducing Electricity Usage

- Combined Heat and Power

- chp

- grid

Related items

-

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries -

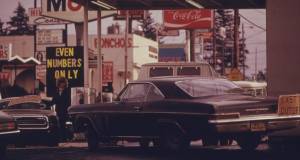

The first oil crisis

The first oil crisis -

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March -

Energywise Ireland open new renewables showroom

Energywise Ireland open new renewables showroom -

Passive house district uses one-third the heat of typical apartments — report

Passive house district uses one-third the heat of typical apartments — report -

Together in Electric Dreams

Together in Electric Dreams -

Passive House Plus back issues now freely available online

Passive House Plus back issues now freely available online -

Passive House Institute launches new cert categories

Passive House Institute launches new cert categories -

Passive house: an alternative method of meeting Part L?

Passive house: an alternative method of meeting Part L? -

Do Ireland’s energy efficiency regulations penalise energy efficiency?

Do Ireland’s energy efficiency regulations penalise energy efficiency? -

Ireland’s energy roadmap — have your say

Ireland’s energy roadmap — have your say -

Viessmann to showcase pioneering fuel cell system at Ecobuild

Viessmann to showcase pioneering fuel cell system at Ecobuild