- Renewable Energy

- Posted

Super powers

The development of sustainable building in Ireland has had to wait for the public to become concerned about energy supply, climate change, and the implications of living in draughty, damp buildings. Much of the established low energy know-how emanates from countries where cold winters drove innovation. Drawing from 50 years of research and development between the Canadian government and housing industry, the Super E programme may be just what Ireland needs, as John Hearne discovered at a new development in Rosslare.

The country’s largest development of Super E homes is now under construction in Rosslare, County Wexford. ‘Portside’ consists of 43 houses being built to the Super E specification. While all incorporate a high insulation spec, air-tightness is the hallmark of a Super E home. In the first house completed in Rosslare, blower-door tests returned an astonishing air-tightness result of 0.29 air changes per hour at 50 Pascals – less than half of the requirement for a certified passive houses.

Jeff Culp of the Super E office says the theory underlying the methodology is very simple. “The house is a system. You can’t change one part of the house without it affecting other parts of the house. So for example, if you want to make the house more energy efficient, you reduce air leakage, but if you reduce air leakage, then you have to ventilate the house. The goal of Super E has always been to reduce the energy consumption of our housing, but in doing so we’ve created many other benefits. These houses have extremely good indoor air quality. They’re dust free and they also resist noise from the outside.” The first house completed on the development has been awarded an A3 building energy rating, yet, as Culp is keen to point out, this has been achieved without over-reliance on renewable technologies. Aside from solar thermal panels and the necessary HRV system, there’s no ‘eco-bling’ in evidence. “The extremely high energy ratings we’re getting are about a third or so better than most new housing in Ireland and we’ve achieved that by reducing waste, and that means reducing uncontrolled air leakage. Compared to a PV system or a geothermal system, that sounds pretty boring, but it may be you won’t get a better building envelope than you will find here.”

Openings for services are designed into the build and then sealed up with foam after the trades have finished

These are system built houses. Canadian construction company DAC International, working with Super E, adapted the plans supplied by the developers to the Super E model, then built and shipped the panels to Ireland for assembly. A DAC trainer came over to assist in the early part of construction, while the whole process was overseen in Rosslare by consulting engineer John Quigley. He talks through the wall build-up.

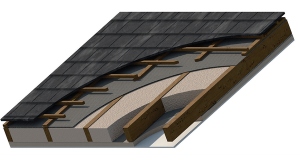

“First there’s a 90mm stud, then a layer of plywood sheeting. That’s fixed every 150mm on the studs, then onto that you’ve two layers of polyiso (a closed cell, rigid foam board insulation), each 38mm thick. That’s then battened. There’s a 12mm to 15mm gap left between the slabs of polyiso.” The simple logic behind so large a gap, he explains, is to ensure that it gets filled. With a smaller gap, you’re never quite sure if the foam has penetrated right through to ensure a tight seal. Excess foam is trimmed off and the joints are then taped up with Tyvek tape. “The spray foam is one layer of air-tightness.” Quigley explains. “We did a blower door test before we taped it up, just on the foam, and we got very good results with that alone. The tape is another layer. We did another test once that was on and came out with 0.7 ACH. Then we found when finished with Rigidur panel on the inside and the Aquapanel system on the outside, we were getting down to 0.3 ACH, so every layer helps. It was an overall system that delivered air-tightness. It wasn’t just one thing or the other.” In addition to the polyiso fixed to the plywood sheeting, the stud is packed with mineral wool. A vapour barrier is fitted over that, followed by the Rigidur panelling. Roof build up is very similar to wall build-up, except that there is one layer of 38mm of polyiso attached to the plywood sheeting over the rafters. As in the wall, the gaps are filled with high quality expandable foam, then taped, as are the joints between wall and roof. To make up for the loss of one layer of polyiso, the rafters are filled with 250mm mineral wool, or, in some houses, the Icynene insulation system. Gable ladders arrive fully made up onsite and are screwed into place using proprietary fixings. “The other important junction is where the wall meets the floor,” says Quigley. “Here, the radon barrier is left out and turned down. The damp course is lapped over the radon barrier and that’s sealed, then the Tyvek is used to seal the damp course off to the wall. In a lot of houses, this is a really vulnerable area. You’ll get a lot of air leakage here where the floor slab meets the wall. A lot of work went into making sure that doesn’t happen here.” 100mm of insulation in the floor is then topped with a 6 inch screed, also containing GGBS. U-values are as follows. Walls: 0.17 W/m2K, roof: 0.14 W/m2K and floor: 0.25 W/m2K.

Blower door tests are carried out at various stages of construction as air-tightness is the hallmark of a Super E home

The attraction in the Super E system, says Quigley, is its simplicity. Because the stud does not go from inside to outside, cold bridging is eliminated. All openings for services are designed in, predrilled in the factory, then sealed up with foam after the trades have finished. “The first house, on our first try, was up and the roof slated in eight days. That’s from a standing start with the foundation in place.” The detail book supplied by DAC International gave the construction team everything they needed to know. “Follow that,” says Noel Byrne of developer/builder Millharbour, “and you can’t go wrong.” One other feature which drew the design team to the Super E system was the fact that air-tightness occurs outside rather than inside the stud. As John Quigley points out, air-tightness tests can be conducted – and great results achieved – before external or internal finishes. Moreover, having an air-tightness layer towards the outside of the envelope drastically reduces its vulnerability to accidental penetration during first and second fixing. Similarly, if the householder wants to, say, install additional sockets down the line, he can do so without threatening the integrity of the conditioned space.

All timber used in the construction of the panels is FSC certified yellow pine. Engineered joists are used rather than solid wood, thereby reducing creaking in upper floors. The key attraction in using engineered timber however is that it is built from younger trees and junk wood. “That means,” says Jeff Culp, “we can replace the trees a lot faster.” He says too that shipping the panels from Canada does not reduce the sustainability of the system. “We’ve done the calculations. It depends on where you bring it from in Canada, because bringing it over the ocean has almost no impact. Land transportation is the cost. We did the calculations for southern UK, which is a little further land transportation than here, where the port’s right at our doorstep. The amount of energy that you use to bring the wood over is repaid within 2.5 years of the house sitting here, because the house saves so much energy. The house, presumably, is going to sit here for 200 years, so you keep saving energy after you’ve already paid back the carbon you required to bring it over. And in terms of carbon, there’s a whole bunch of carbon in this wood that’s not in the atmosphere.”

The houses are clad in the Aquapanel cement board system

Jeff Armstrong of DAC explains that the plans arrived to their offices as traditional brick and block construction. “We essentially redrew them with our particular timber frame system, and we hired an engineer here in Ireland to review all of the structural issues. Then we built it, shipped it and sent a trainer over to work with the local guys to erect the first building and help them to understand the practical business of how things are numbered and labelled….There’s a lot of air-tightness detailing that would be unfamiliar to the guys here, so he was there to walk them through that. He left around the time the roof was being finished on the first building, but some of the blower door tests they’ve got since he left have been even better.”

Armstrong also emphasises the simplicity of the system. “There’s nothing fancy about this. It’s just basic building science. It’s a lot of experience, a little bit of training...plus what you must have – and we definitely have it here – is a competent builder who really wants to do a good job. They’ve got the right mindset, they’ve got control over what happens on the job site. We could knock ourselves out back in Canada doing stuff but it can end up a mess if you’ve got somebody on the other end who doesn’t care about what they’re doing. That’s really important.” He too makes the point that the A3 rating was achieved without recourse to a suite of renewable technologies. “When you build a really good building envelope, the investment you do make in renewable energy technology is really worthwhile because the energy load is so low, you have a substantial impact with the energy you install. The key is to have a really good building envelope to start with, and after that it’s just icing on the cake,” he says.

Two Wikora flat plate panels will supply most hot water needs

In addition to the polyiso incorporated in wall and roof panels and the mineral wool in rafters and studs, several of the attic spaces in Portside feature the Icynene insulation system. “It’s an open cell water-based foam,” says Declan King of GMS Building Services, who supplied and fitted the product. “It’s predominantly water based – 1 per cent product to 99 per cent air and it’s sprayed into the timber frame.” Excess foam is then cut away and the surface finished as required. In Portside, Icynene has been pumped into the spaces between the rafters in the attic. The key attraction of the product is that in addition to its thermal properties, it also boosts air-tightness. “It enhances the performance of a house, creating a good air-tight barrier and reducing energy loss by up to 50 per cent.” Carrying the CE mark, and approved by both Irish and British Agrément boards, King says that using the foam as a whole house solution saves on cost by removing the need for additional insulation or air-tightness measures.

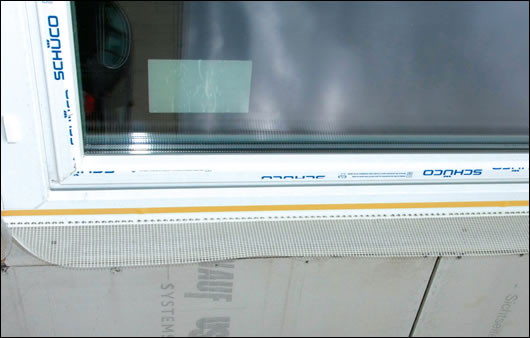

The triple glazed windows are Oliva CT 70 units, a PVC window with a steel reinforcement. “The frame,” says Kevin Jordan of the company, “has a U-value of 1.4 W/m2K, and the triple glazing of argon filled glass with a low E coating has a U-value of 0.7 W/m2K. That brings the whole unit down to 1.2 W/m2K.” Opening vents are all tilt and turn, he says. “The great thing about that is the fact the seals are so much better. With a normal Irish window, you have closers either on the bottom or along the side. You won’t have both. But with our windows, closers along the bottom, top and the sides mean that when you close that window, it’s sealed tightly. That’s why they were able to manage such a good blower door test. There’s no air leakage and no heat transfer.” Oliva also supplied Schueco front and back doors for each of the houses. The laminated safety glass used in these units has better thermal properties than the windows, delivering a U-value of 0.9 W/m2K. Under an arrangement with Schueco, all unused Oliva profiles are recycled by the company – they guarantee that 25 per cent of window profiles are made from recycled materials.

In some houses Icynene foam insulation is used between the rafters in the attic spaces

Internal walls are finished with Rigidur, a moisture resistant fibreboard from Gyproc. It combines gypsum, cellulose fibres from recycled paper and water to form a dense sheet material. “It’s got high impact strength and racking strength,” says Evan O’Keefe of Gyproc. “So it works particularly well with timber frame. You can hang 30Kg from a single point load using a conventional screw, and using a spring toggle type fixing, you can hang 55Kg.” Installed, taped and jointed, and finished in just the same way as standard plasterboard, Rigidur boasts a thermal conductivity of 0.35 W/mK. The 12.5mm board comes in a standard 1.2m by 2.4m size, though bespoke sizes up to 6m by 2.5m are available, enabling complete wall panels to be constructed from a single board without the need for jointing. Both the product and the manufacturing process have been awarded a certificate for sustainability from the Rosenheim Institute of Construction Biology and Ecology.

Ecocem low carbon concrete is used in the foundation and floor slab. David O’Flynn of Ecocem says that substituting away from conventional concrete gives each house a saving of 6.7 tonnes of carbon. “That’s the equivalent of leaving two cars at home for the year. Effectively, the first year the family moves in here, if they’re a two car family, it’s as if they get to drive carbon free for the first year, based on the amount of CO2 that’s been saved thanks to using this concrete instead of conventional concrete.” Ecocem is made from GGBS, a by-product of the steel industry imported from Europe, ground in Dublin, then transported to individual concrete plants to complete the manufacturing process. Jim Boggan of Millharbour also runs a concrete business which produces low carbon concrete using the GGBS supplied by Ecocem. Despite the fact that the raw materials have to be shipped from the continent, the embodied energy used in manufacturing compared to that of conventional cement gives Ecocem a vastly superior carbon profile. “When you make cement, you’re burning limestone.” O’Flynn explains. “If you burn limestone without using any energy, you release about 550Kgs of CO2. Add in the fossil fuel in the manufacturing process and = electricity, that brings it up to around 900Kg per tonne cement laid. For Ecocem, the equivalent figure is around 30Kg.” Speaking to David O’Flynn subsequent to the launch of the Portside development, he reports that as a result of a carbon offsetting programme instigated by the company, that figure has now been reduced to zero.

While in others 250mm mineral wool is selected

Ecocem looks different to conventional cement. “You’ve got consistency in the colour.” says Jim Boggan. “It all comes out pure white. You don’t have any blemishes.” In addition, while Ecocem lasts up to twice as long as conventional cement, it doesn’t cost any more.

Instead of the conventional block or brick outer leaf, Portside houses are clad in the Aquapanel cement board system from Greenspan, which boasts only around 10 per cent of the carbon footprint of a masonry wall. “It’s a completely ventilated system,” Chris Scanlon of Greenspan explains. “You’ve vertical batons on your structure and it ventilates out through the soffit on top. You install it, tape and fill the joints, put on a base coat, a mesh, a primer and finally a textured finish.” The only cement board of its kind in the world, Scanlon points out that Aquapanel is durable and impact resistant and facilitates faster build times compared to conventional finishes.

The windows are Oliva CT 70 units, triple-glazed and argon-filled PVC windows with a steel reinforcement

The mechanical heat recovery ventilation system is a Greenwood Fusion unit HRV1 supplied and fitted by Control Aer in Dublin. SAP Appendix Q listed at 70 per cent efficiency, this very compact unit running at low rate consumes 0.8w/l/sec. Anthony Behan of Control Aer estimates running costs at 0.03c per hour. “When it’s fitted, we commission and balance the unit to get the extract and the supply right, so you get the correct air changes required by the regulations. It’s a plug and play system.” Filters are slotted into the front panel and can be washed or hoovered or replaced as necessary. One of the big advantages of the Fusion unit is its size. Measuring 294mm by 594mm by 495mm, and weighing just 11Kg, it can work in highly restricted spaces. Control Aer has installed these units in bathrooms and void spaces in apartments. To work in these settings, keeping unit noise down is vital. Sound levels at 3m dB(A) are 25 on boost and 15 on trickle. Though it will rarely need to be accessed by the householder, control comes via a built in, intuitively designed LCD display, while humidity sensors in bathrooms automatically boost fan speeds as required. Acoustic flex duct, which features a perforated metal film internally, reduces the incidence of noise as air passes through. “For a fitter it’s a great unit,” says Behan. “It has a digital clock for commissioning. If you’re doing a retrofit for a house, you can change extract and fresh air pipes to suit the space it’s going into...If you don’t have the space, you can have a left or a right handed setting.” This feature also boosts the energy efficiency of the unit; the fewer bends in the duct, the less energy it takes to push the air through.

Water heating comes via two 2.34m2 Wikora flat plate panels, which, suppliers Heat Merchants estimate, will deliver 70 per cent of annual domestic hot water needs. Roof pitch and planning considerations mean that orientation at south south east is not perfect. However, the loss of efficiency is minimal. Under the DEAP methodology, if you’re facing south on a roof slope of 30 degrees, you’ll get annual solar radiation of 1,074 kWh/m2. If the angle is 45 degrees you get 1,072 kWh/m2. If you’re south east or south west at 30 degrees, you get 1,021 kWh/m2, and at 45 degrees it’s 1,005 kWh/m2. The panels have a net receivable efficiency of 82.2 per cent. They feed a 200L DJG stainless steel dual coil cylinder with thermostatic control. In addition to the immersion, there’s also a back-up feed from the space heating system – a condensing oil boiler. “As long as there’s a differential of seven degrees between the bottom of the cylinder and what’s on the roof,” says Ian Stafford of Heat Merchants, “the solar will operate. You then you have a motorised valve worked off the oil. At a certain stage, it will check the temperature and if it’s under the pre-set temperature – say 60oC – the thermostat will call on the boiler and top up your hot water.”

Oliva also supply the Schuco front and back doors which are sealed tightly to prevent air leakage

Developer Noel Byrne of Millharbour says that the design team gave serious consideration to the establishment of an ESCo to facilitate a district heating system. The collapse in the housing market however made this solution more or less unworkable. “You would have to have all of the houses sold straight away and lived in straight away, otherwise we would have to start putting money in to keep the system going, so it wasn’t a runner. Five years ago we would definitely have done it.”

Cost-wise, Byrne says that while going the Super E route is slightly more expensive than a conventional build, you could not achieve this quality of building envelope as cheaply. “We wanted to build an air-tight house. We’ve always been aware of air-tightness but we felt we couldn’t really achieve it with a block house.” The design team trawled through a variety of timber frame systems before settling on the Super E methodology. “This is the best on the market and I think we’ve proved it,” Byrne says.

The timber stud walls are packed with mineral wool

Because these houses carry the Super E brand, they are all tested at the end of the construction process to ensure that the minimum standards laid down by the organisation are met. “The end of the story is that we check,” he says. “It’s all third party verified...We looked at the walls, are they going to work? Are they going to collect moisture, is the house going to be durable? What are the U-values? And then when it was all finished we did the blower door test, we did the ventilation commissioning, so I know it’s balanced, and I know there’s flow going into all the habitable rooms.”

Selling agent Adrian Haythornthwaite says we’re nowhere near the point where low energy housing can command a premium over conventionally built homes. “Carbon isn’t a language the man on the street necessarily understands….He does understand simple things. He does understand that these houses will take half a tank of oil to heat them for a year whereas your average house in Dublin will take two. He understands that. He understands when you shut the window, you can’t hear noise outside, he understands that that’s going to improve his life, he understands that his carpets won’t fade because you’ve got the extra UV barrier on the windows. I think the buying keys are probably more related to health. That is the tone of the questioning that I’m getting. You can live in these houses unaffected by hay fever, you don’t have problems with mites and stuff like that.”

Rigidur, a moisture resistant fibreboard

Jeff Armstrong of DAC International makes the point that the current climate is having a beneficial impact generally on the quality of new housing stock. “All this talk about controlled air leakage and reduced thermal bridging and other features really fell on deaf ears during the boom. Essentially builders were selling everything they put up, whether it was of good quality or not and they really didn’t have time to listen to anything that different, but times have certainly changed. It’s the buyers who are in charge now, and the few of them who are still on life support can afford to be much more selective than ever before. Add to that the changes to the building regulations and their strength and emphasis on environment, suddenly a project like this looks a whole lot more like the future of housing in Ireland.”

Selected project details

Developer/main contractor: Millharbour Construction

M & E/structural engineer: John Quigley and Associates

Build system: DAC International

Polyiso insulation: GMS Insulation

Windows & doors: Oliva

Rigidur boards: Gyproc

External cladding: Greenspan

Heat recovery ventilation: Control Aer

Solar panels: Heat Merchants

- Articles

- renewable energy

- Super powers

- Super E

- A3 Energy rating

- DAC International

- Aquapanel Cement Board

- Wikora

- Icynene

Related items

-

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries -

The first oil crisis

The first oil crisis -

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March -

Energywise Ireland open new renewables showroom

Energywise Ireland open new renewables showroom -

Together in Electric Dreams

Together in Electric Dreams -

GMS launches new Icynene spray foam insulations

GMS launches new Icynene spray foam insulations -

Icynene secures BBA certification

Icynene secures BBA certification -

Passive House Plus back issues now freely available online

Passive House Plus back issues now freely available online -

The builder's view - why passive house doesn't cost extra

The builder's view - why passive house doesn't cost extra -

Passive House Institute launches new cert categories

Passive House Institute launches new cert categories -

Passive house: an alternative method of meeting Part L?

Passive house: an alternative method of meeting Part L? -

Do Ireland’s energy efficiency regulations penalise energy efficiency?

Do Ireland’s energy efficiency regulations penalise energy efficiency?