- Dispatches

- Posted

New build homes face emerging ventilation crisis

Despite increasing standards of insulation and airtightness, housing developers face few requirements to provide better ventilation and indoor air quality for new home buyers — beyond knocking extra holes in walls. But as reports of condensation and mould affecting new housing developments continue to surface in both the UK and Ireland, and research indicates many new homes may have poor indoor air quality, are developers finally waking up to the need for properly engineered ventilation systems?

This article was originally published in issue 19 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

Despite the fact that we’ve seen some very significant enhancements in the energy performance of new homes on both sides of the Irish Sea, there is one element of residential construction that has proven almost totally resistant to improvement: ventilation.

We may have made our homes more airtight, beefed up the insulation and installed much better windows, but the quality of air in these homes might be – if anything – getting worse.

Changes to Irish building regulations introduced in December 2011 mean that all new homes are designed to use 60% less energy than homes built to 2005 standards, which on average translates to a mid A3 building energy rating. So far so good.

But research carried out by this magazine has revealed that 63% of these homes are reliant on so-called ‘natural’ or ‘background’ ventilation. This means nothing more than drilling a hole in the wall and slapping a grille over it. Despite the fact that there is little evidence that this is an adequate solution, it’s entirely permitted by regulations. And because it’s the most cost-effective recourse out there – if your sole concern is meeting the requirements in the government’s guidance on ventilation – it is the default choice of most developers.

A detail described by ventilation consultant Ian Mawditt as fairly common: the bathroom extract and supply are so close that recirculation of stale, moist air – and odours – are inevitable Photo: fourwalls

Meanwhile, at an event organised by the Green Register in June, Aecom and The Zero Carbon Hub presented findings from an as yet unpublished report on the ventilation installation and performance of almost 90 UK new builds. They uncovered a startling range of problems, including poor air quality, a lack of commissioning of systems, and insufficient flow rates in fans. Only three of the homes surveyed were actually compliant with Part F of the building regs (the section that deals with ventilation).

It’s hard to find a definitive reason why ventilation has become the poor relation in the houses that we build. Given the choice, none of us would opt to live in a house where the air did not circulate, or was clogged with pollutants. And yet we do.

Andrew Lundberg of Passivate is a passive house consultant well placed to comment on the emerging ventilation crisis. He makes the point that central to the problem is the fact that many of our new houses are becoming more airtight almost by accident. Even when there is no conscious effort to focus on airtightness – as would be the case with a passive build – a combination of factors is making better airtightness a default choice.

Mould diagnosed as caused by lack of air circulation Photo: www.mouldsolutions.ie

“I’m talking simply about the use of new materials that have come onto the market in recent years, and the most common ways of building now,” he says. “Wet renders inside buildings, taping windows, and the use of a membrane across a roof...Without taking care of the finer detail of how those things come together, these alone can bring us down to typically two or three permeability in many cases.”

Permeability measures unintended air leakage through a house. Irish building regs stipulate that new dwellings should achieve a pressure test result of no worse than an air permeability of seven (measured in metres cubed per hour per metre squared, at a pressure of 50 Pascals — or m3/hr/m2 at 50Pa). The ‘two or three permeability’ that Andrew Lundberg routinely encounters is much better than the unambitious regulatory threshold, and it may actually be standard practice: Passive House Plus analysis of SEAI data indicates that the average airtightness test result of new homes built to the latest version of Part L is 3.7m3/hr/ m2.

Hole-in-wall vents are often blocked due to the discomfort caused by uncontrolled ventilation. Photo: www.mouldsolutions.ie

To state the obvious, the more airtight the home, the more important ventilation becomes, and the regulations do acknowledge this. Part F stipulates that if a naturally ventilated building reaches an airtightness level of five cubic metres of air leakage per hour for each square metre of envelope area during such a test, the developer must increase background ventilation by 40% of clear area. That is, he must drill 40% more holes in the walls, or increase the core diameter of the holes by that proportion.

Andrew Lundberg says: “I had a project recently where the builder had built well below five air changes per hour (ACH), but wasn’t aware of the implications, and nor was anyone else involved. They realised there was a problem when they started to get mould in the houses.”

“Now, these houses had been very well built, there was no issue around continuity of insulation around junctions, or anything like that. It was simply that the humidity wasn’t being dealt with because the building was so airtight and well insulated.”

As the onsite consultant, Lundberg proposed a demand controlled mechanical ventilation solution, which worked out at just under €900 per dwelling. But this was not the cheapest solution. The cheapest solution was to drill 40% more holes in the wall. That’s what happened, and sure enough, the mould went away.

The problem with this ‘solution’ however, is that these holes are so big and there are so many of them, that they will almost certainly lead to draught issues during the winter. And when the occupants move in, at least some of them will block up the vents. The draughts will go away, but back will come the mould.

Mould at the junction between an external wall and a vaulted ceiling in a naturally ventilated low energy extension Photo: Simon McGuinness

The situation is more or less identical in the UK. In naturally ventilated dwellings, once the air permeability drops below an air permeability of five, background ventilation provision has to be increased. One increasingly common alternative however is to install a decentralised mechanical extract ventilation system (dMEV).

A decentralised system is essentially individual fans installed in wet rooms (in the same way as intermittent fans) that operate continuously, and may boost either manually or automatically during periods of higher humidity. With this strategy, you are allowed to build as airtight as you like.

Ian Mawditt runs independent building performance company Four Walls. He explains that one of the advantages of centralised ventilation systems is that fans are located in an enclosure (often acoustically-treated) and are tucked away in voids or lofts, to prevent noise becoming a nuisance.

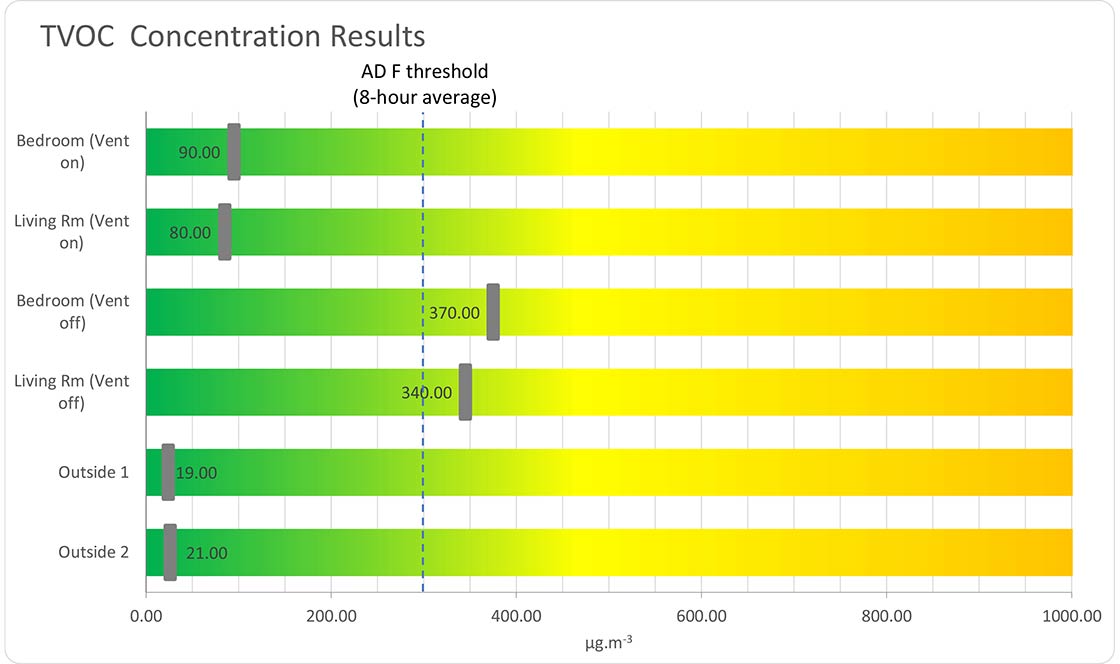

Total volatile organic compound readings from Ian Mawditt’s deep retrofit in Bristol reveal a significant increase in VOCs when the MVHR system is switched off – which may hint at how a low energy home with natural ventilation would perform with vents closed

“But if you put the fan on the room side [as with dMEV], even if it’s running at a lower rate than an intermittent fan, it’s still going to create a constant background noise. In most homes I’ve visited, noise has been a major issue for residents, and this frequently leads to systems being switched off.”

“If constantly operating fans are turned off, whether centralised or decentralised, there is a significant risk of under-ventilation, which in turn will lead to poor air quality. This is because it is only required to put smaller ventilators [compared to natural ventilation openings] in bedrooms and living rooms to act as air inlets. If the fans are turned off then there will not be a negative pressure inside the home to provide sufficient ventilation. With dMEV there is a greater risk of systems being switched off, and without a negative pressure induced by a fan, the ventilators will be too small for sufficient natural ventilation.”

The second way of dealing with the ‘accidental’ airtightness issue is no less retrograde. Some developers who find themselves inadvertently below the threshold, will simply cut a hole somewhere in a membrane. They deliberately wreck the energy performance of the house simply to avoid the necessity of drilling more holes.

Andrew Lundberg points out that this approach can create even more problems. Stabbing the membrane at some arbitrary point means that when atmospheric conditions prompt air movement, an excessive amount of the humidity in the space will exit through a single tear.

“All of a sudden,” says Lundberg, “you’ve got a massive focus of moisture in the form of vapour at a small number of locations in the building. It could, for example, be a roof membrane that takes the cut, and if you cut a roof membrane, you’re never far from a piece of timber, so you could be introducing a local condensation risk, which could lead to mould growth on local surfaces at the location and longer term damage to the building fabric.” It’s the invisibility of this risk that makes it so insidious. If a radiator doesn’t work, you will know instantly. But if the ventilation strategy does not deliver good air quality, and has instead introduced condensation into the building structure, you may not know about it until it’s too late.

Even assuming you accept the 40% more holes and put up with the winter drafts, hole-in-the-wall systems won’t keep the air fresh because they are systemically flawed. They rely on variations in pressure and temperature to move air from the inside to the outside. Relative differences in humidity, CO2 and other pollutants will not prompt the required movement in the air; these contaminants will just sit there, no matter how big the hole in the wall, until such time as temperature and/or pressure variations change conditions.

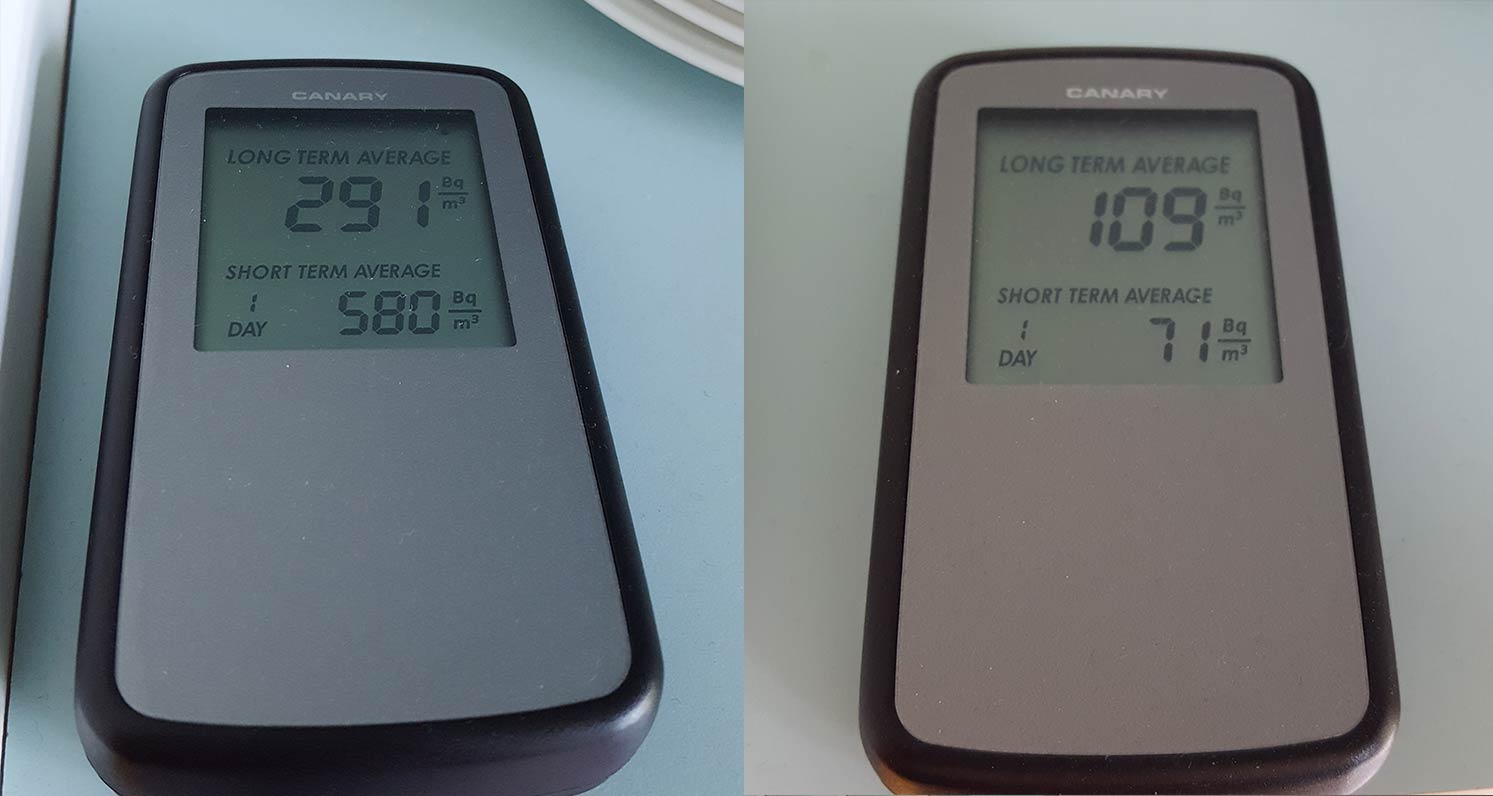

Radon readings from Ian Mawditt’s house with MVHR system switched on and off reveal that lack of ventilation would cause the cancer-causing gas to accumulate above safe levels. Photos: fourwalls

Andy Lundberg puts it like this: “The parameters that dictate how much fresh air we need are not the parameters that affect how air moves naturally based on current part F.” By contrast, demand controlled and heat recovery ventilation (HRV) systems have sensors which will adjust fan speeds based on CO2 and humidity levels.

Maurice Flynn of Flynn Heat Recovery Systems says he gets at least ten calls every year from people with houses two or three years old – all built to high standards – with mould and condensation issues.

“Some people deal with condensation and mould by opening windows every morning and routinely cleaning mould from affected areas. The ones that contact us are looking for a long term solution. We are only one small HRV supplier in Ireland, installing only a few hundred per year. How many other guys are out there doing HRV? I’m sure the enquiry rate for all providers is huge, and these are new houses with serious problems.”

Like Andy Lundberg, Flynn has been well placed to observe developer antipathy to demand controlled and heat recovery ventilation systems. He points out that that antipathy isn’t all about cost. The fact that there is no regulatory body to administer or police the installation and commissioning of ventilation systems means that when things go wrong, it’s on the systems themselves that prejudice tends to settle.

In the absence of an independently accredited ventilation professional, it generally falls to the plumber to source and install mechanical systems.

“We have invested heavily in equipment like anemometers, sound meters and air quality monitors,” says Flynn. “A good quality commissioning anemometer costs at least a couple of grand... It is very difficult to expect any contractor who is not installing these systems on a daily basis to a professional standard to invest in this equipment. That’s a sticking point, and so is this: no one checks the work that installers do, there’s no one to say that this or that system meets the required standard.”

It would be wrong however to suggest that nobody’s doing it right. When phase one of the Silken Park development in City West, Dublin was completed in 2007, the 22 apartments and 33 houses were built to 2002 regs, and featured partial fill cavity walls and standard hole-in-the-wall ventilation, with no provision for airtightness. Phase two, which was recently completed, includes 26 houses and three apartments. Each boasts highly insulated, single leaf walls, passive standard airtightness and demand controlled ventilation.

And phase three – on which work progressed this autumn – will showcase 59 certified passive houses, each of which will feature mechanical heat recovery ventilation. The company behind the scheme, Durkan Residential, is run by brothers Patrick and Barry Durkan. Patrick Durkan explains that the company’s evolution to the point where they are about to embark on the mass production of passive houses came primarily through a focus on quality.

“Our main concern, our main focus,” says Durkan, “is to achieve a great product. To do that, obviously, you need airtightness. But to counteract that, you have to have ventilation. If you don’t go the ventilation route, it’s all in vain.”

Large scale developments generate the economies of scale necessary to bring down the per unit cost of fit-for-purpose ventilation systems, but until the regulations insist on something better than ‘natural’ ventilation, most developers are likely to just continue on knocking holes in walls.