- Design Approaches

- Posted

Buildings need better overheating models to guarantee future comfort

Building designers need to undertake much deeper analyses of overheating risks, and do so under future climate change scenarios, in order to ensure their buildings can adapt and remain comfortable for occupants in a warming world.

This article was originally published in issue 28 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

That’s according to Richard Tibenham of Greenlite Energy Assessors, energy and thermal comfort consultants, who also called for a much more integrated design approach between architects, engineers and contractors to ensure long term comfort for building occupants.

“The magnitude, duration and frequency of heatwave conditions is increasing across Europe as a consequence of climate change, thus the demand for sufficient safeguards is becoming more pertinent,” Tibenham said.

“Low energy buildings are at an increased risk of overheating due to inherent design characteristics such as increased levels of airtightness and insulation. Ill-conceived glazing quotas, glazing orientation and shading strategies can present overheating risks, which can be extreme at times.”

“There is no requirement under the current UK building regulations to assess overheating risks, and this is manifesting in a moderate number of buildings incurring overheating problems or excessive mechanical cooling loads.”

“Predictive weather data combined with accurate thermal modelling suggests that the vast majority of buildings are woefully unprepared for a changing climate.”

Tibenham said that the quality of architecture in response to overheating risks varies significantly, with some schemes taking sensible design measures from the early design stages, whilst other schemes take very little consideration of overheating risks at all. Too often, he said, schemes rely on low-g glazing as a cover-all response to excessive glazing quotas, however this can in turn increase winter time heating loads.

He said that in the event that an overheating analysis is undertaken, these often set the bar at CIBSE TM52 compliance using Design Summer Year (DSY) 2005 weather data. “From my own works, whilst these buildings may pass the code when assessed using DSY05 data, they very often fail when tested against 2030 weather data, let alone 2050 or 2080.”

Richard Tibenham of Greenlite Energy Assessors

“I suspect the outcome will be an increase in the amount of retro-fitted air conditioning systems, which is obviously undesirable when attempting to decarbonise the grid at the same time. This could be avoided however if a longer term stance to summertime comfort were adopted and buildings were tested under the weather conditions likely to be experienced during their operational lifetime.”

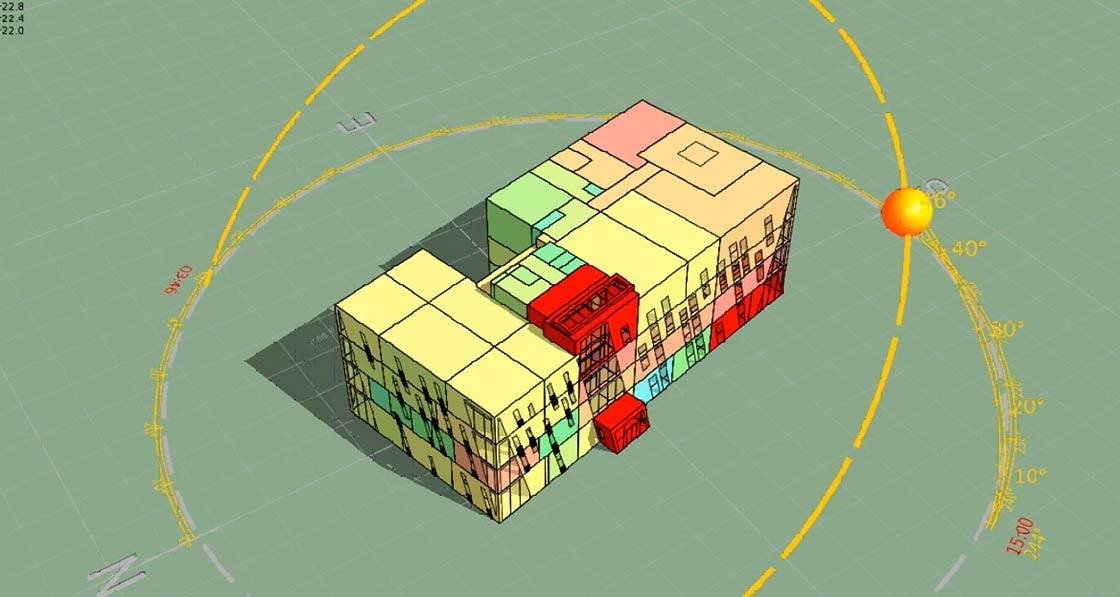

Dynamic thermal models

Tibenham added: “A dynamic thermal model or DTM can be helpful for any building, and can often turn up some useful and highly detailed design data that would otherwise go unacknowledged. With respect to passive house schemes, a DTM can be incredibly useful in determining localised indoor environments, since the PHPP deals with the building as a whole, rather than as a cluster of interrelated environments.”

“For larger commercial buildings in particular, this level of analysis can be highly valuable in avoiding potential localised risks. If sufficiently detailed, the models can also be very useful in assessing the behaviour of complex HVAC networks, and the impact of various control strategies and set-points.”

Tibenham said that undertaking a reliable DTM provides a looking glass into the behaviour of a building, and allows the trends and behaviour of various building physics phenomena to be better understood. This understanding, he said, can be fed back into the design cycle and used to better inform future buildings.

“From my experience, building services engineers tend to read the reports, but understandably focus on black and white measurable performance objectives such as Part L outcomes and BREEAM. Many main contractors and architects neither read or understand the reports, leaving the contractual responsibility for thermal comfort solely with the building services engineer. This results in the same problems re-occurring, with the building form and fabric presenting problems which require a HVAC response.”

“I am looking to engage with architects and contractors who wish to put the thermal and energy performance of the building at the core of the design process, with the building fabric and building services operating as an integrated system, rather than as separate entities. Early engagement is key to achieving optimum outcomes.”

For more information see www.greenliteea.co.uk.