- Design Approaches

- Posted

Force of Habit

Two years ago Construct Ireland ran a case study on Mater Orchard, a Mercy Sisters convent building that successfully balanced cutting edge technologies with pragmatic green design. Such was the success of that building, its architects were commissioned by Mercy Sisters in Limerick to repeat the feat. John Hearne visited the freshly completed building to find out how they fared

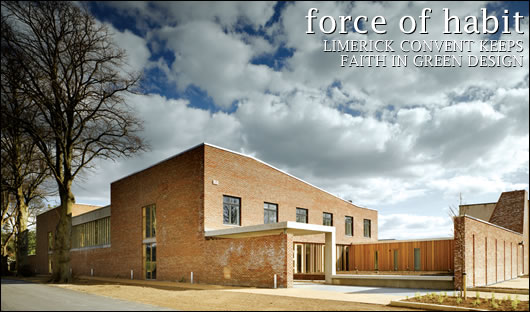

The new convent at Mount Saint Vincent in Limerick brings together a shopping list of sustainable technologies. Together with biomass space heating, solar water heating, an innovative passive ventilation strategy and a high degree of air-tightness, there’s also a green roof and a rainwater harvesting system. None of this however is apparent as you approach the building. Tucked away behind a line of mature trees, the new building stands at the southern edge of the existing convent’s front garden, which is dominated at its western end by the formidable gothic façade of the nineteenth century convent itself.

“It doesn’t suit elderly living, and it’s far too big.” says Philip Crowe, director of architecture with design team leaders, MCO Architecture. “Our brief was to design a home; private, but not defensive. A home for a community with a particular age profile and a requirement for privacy.” From a design point of view, it was essential that the new building remain subsidiary to the old, that there be competition between the two. This brief was facilitated on one hand by the screening line of mature trees and on the other by the uncompromising dominance of the existing pile. To counter its austerity and coldness, the external walls of the new building combine red brick with cedar cladding and large window screens. “It had to contrast with this building; you couldn’t imitate the old convent in terms of the stone and we wanted to use a small unit to give it a bit of warmth as well. The brick has worked very well in that regard; it’s warm and it does match in with redbrick on O’Connell Avenue.” The building itself is structured around three gardens, a kitchen garden to the front, a community garden in the middle and a private garden to the rear. The twenty-two bedrooms, most of which are located in the upper storey overlook one or other of these gardens, while extensive glazing through common areas takes full advantage of the southerly orientation.

While aesthetics did form a vital part of the design brief, Sister Anne Doyle of the Mercy Sisters explains that the decision to run with a strong sustainable strategy stems from the long-established ethos of the community. “We would want as Mercy Sisters to live in harmony with the earth and if we don’t follow that principle when we can, in building new buildings or renovating old buildings, we’re saying one thing and doing another thing…We do believe we are an integral part of the earth and not a dominant part of the earth.”

Throughout the project, MCO drew heavily on their experience with the Mater Orchard building, also a Mercy Convent, completed three years ago in the grounds of the Mater Hospital in Dublin. In addition to a very similar brief from the client, many of the sustainable elements tried and tested in Mater Orchard have been re-introduced in Limerick. A key advantage in the west lay in the site itself. Because the team essentially had a greenfield site to work with, there was a much greater degree of design freedom than had been available in Dublin “We were able to do a very rational and efficient building,” says Crowe, “with double loaded corridors which are much more efficient for the bedrooms. It’s a simple thing but it actually makes a lot of difference, not least in making the building very cost effective.”

The design team required that visibility through courtyard glazing be unimpeded by structure and extensive glazing throughout takes full advantage of the southerly orientation

There were a number of engineering challenges. “The roof structure is designed for the heavier roof loading both for the (green) sedum roof and the water it will retain.” says Enda Hoey of Barrett Mahoney Consulting Engineers. “Also the roof structure and the sedum are used to attenuate the rainwater flow.” To facilitate the range of sustainable strategies on the build, the engineering team opted for a flat slab structure. “The green roof, rainwater tanks, solar panels, the flexibility for reworking the internal layouts and also the passive ventilation system, all led us down the road of a flat slab structure.” The design team required that visibility through courtyard glazing be unimpeded by structure, while the absence of downstand beams about the perimeter of the building also facilitates uninterrupted air flow. All of the columns are now contained in jumbo stud partitions. “This building,” says Philip Crowe, “is future-proofed in that you can change the configuration downstairs. The building is designed for assisted living, for residential community living, and will continue to fulfil that function in future years.” Sister Anne Doyle says that element of the design was vital for the community. “Our buildings must be capable of being lived in now and for the long haul because we don’t expect that we will be moving. We have lived in our buildings for hundreds of years. Future-proofing is a value we aspire to.”

Crowe explains that the original conception had been a conventional block build, but because U values were falling short of requirements, changes had to be made after tender. “We would generally use full-fill cavity insulation, but our supplier said don’t use full-fill cavity in this location because it’s so exposed. This is the west. We were advised that full-fill cavity insulation wasn’t suitable for wind-driven rain; and that meant we could only use 60mm in the cavity.” Because of this restriction, the team decided to change from a block inner leaf to timber, thereby giving sufficient depth to install an additional 150mm of rockwool. This hybrid construction method, also used in Mater Orchard, delivers a wall U value of 0.19 W/m2K. “We detailed the whole thing very carefully to ensure no cold bridging anywhere in the structure, as well as to achieve a clean architectural finish.” says Crowe. 150mm of Bauder rigid insulation in the flat roof and 250mm in the pitched roof deliver a U value of 0.12 W/m2K. 100mm of TF73 Kingspan Thermofloor in the floors gives a U value of 0.1 W/m2K while that combination of 60mm of Kingspan K8 and 160mm of rockwool in the walls together achieve a U value of 0.19 W/m2K.

In the lower floors and the communal spaces upstairs, large, cedar window screens are fitted with Pilkington K glass with an argon fill and a low emissivity coating to give a glass U value of 1.2 W/m2K. The window screens themselves, supplied by Wood In Design in Kildare are built from Canadian Western Red Cedar, certified under the TRADA-approved CSA chain of custody scheme. The same timber used for external cladding was provided by MTS in Wicklow. “We made an effort to avoid using Iroko in the windows.” says Philip Crowe. “Iroko is the standard, obvious, easy thing to use for large window screens. Though Cedar isn’t grown commercially here, it is grown in sustainable forests in Canada. It’s untreated, so it produces its own protection and it is resistant to fungal attack, so has got excellent natural properties.” Over time, the timber will fade from its current reddish-brown to a silvery grey.

MCO’s earlier project for Mercy Sisters, Mater Orchard

The twenty-two bedrooms all overlook one or other of the three gardens, and Supply Air Windows are installed in each as part of the Dwell-Vent passive HRV system, allowing a constant supply of preheated fresh air into the building

Supply air windows (SAWs) are installed in all twenty-two bedrooms as part of the Dwell-Vent passive heat recovery ventilation system. The SAWs have two panes of glass separated by a 30mm air gap. A trickle vent in the bottom of the timber window frame admits air to the bottomof this gap. Heat escaping through the window, together with external solar energy heats up the air in the gap and this air then rises. It enters the room through another pressure sensitive trickle vent in the top of the window frame. The top vent minimises any reverse flow through the window which might result in a risk of condensation. This preheated fresh air then mixes with the air in the room and as it heats up it is drawn up the passive stack by temperature and pressure differences between the inside and outside environments. The stack chimney with wind cowl ventilates from the ensuite bathroom to the roof while louvers installed between bedroom and bathroom ensure an unbroken flow of air between the two spaces.

“The benefit of it is that you don’t have any noise,” says Philip Crowe, “also there are no moving parts, you’ve no worry about there being any problem in the pipework. The principle thing is you get a constant supply of preheated fresh air into the building.” This is one of the technologies MCO first installed in Mater Orchard. Glowing feedback from the occupants there prompted the system’s reuse in Limerick. “They don’t ever complain about there being a draught, which is something we were worried about, because when you listen to how it works, you wonder, is there going to be a draught? They’re very comfortable, they sleep very well, they don’t get headaches anymore, they don’t hear the traffic, they’re completely happy with it. It feels very fresh inside because the air quality is good.”

Some aesthetic compromises had to be made on elevations which incorporated both cedar window screens and Dwell-Vent’s SAWs. “When we used the Supply Air Windows previously,” says Crowe, “we got a local joinery to make them. Now, Howarths have a copyright on the design so they work with Dwell Vent and basically if you want to use the Dwell-Vent system you have to buy from Howarths. They did make these specially for us, but you are restricted in terms of finish and pattern. The ideal thing would have been to have a slightly different design with a timber finish but that doesn’t work so we have to make some compromises.”

The rather surreal sight of wind cowls terminating the passive stack chimneys surrounded by the convent’s sedum roof

Dwell-Vent have recently stated that they have suspended further contracts pending improvements to the system. In windy conditions on exposed sites, draughts have begun to emerge as a problem. For this reason, the company, with its partners, are currently working on the installation of a regulator within the vents which allow smooth air transfer no matter what the prevailing wind conditions. Asked if he had a concern around the functioning of the system in Mount Saint Vincent, Mike McEvoy, MD of Dwell-Vent said that there is a short-term solution if problems arise. “Simply by putting reticulated foam into the vents, into the slots in the window behind the vents so that we can slow [the air] down is an interim solution, but what we want to do is to make it a better regulator so that it is responsive, and in larger scale projects, we’d have to be able to get that capability into the system.”

If there’s heat recovery ventilation, there has to be air-tightness. With Ireland still very much in the early-adopter phase, site foreman Barry Murphy of Brian McCarthy Contractors says that technical guidance was vital in achieving cost-effective air-tightness. “It’s a mindset…Initially you’re inclined to think weathering and sealing for air are the same thing but they’re not. There’s a completely different thought process. Take the sun tubes that give us light down into the ensuites. To do the air test, all the tubes had to be sealed in the attic space, the void where it comes in through the concrete roof. That’s not normally in your psyche because it does nothing for weathering.” He emphasises the importance of having someone onsite who could advise on both technique and, vitally, the sequencing of trades. “Details and corners of walls, you’re looking, as most builders are, at how will that weather on the outside? How you relate to doing an air test is different. Most of what you have to do, 90% of it is very straightforward, but it’s those little details that catch you. It would have been very difficult without Andre (Gietl from Ecological Building Systems). The issue is, by the time you do the test, it’s so late, if it fails, it’s very expensive to repair.” An air leakage test carried out by Stroma indicated an air permeability rate at 50 pascals of 6.77 m³/(hr.m²). While by no means staggering, the contract team were happy with a result below 10m3/hr.m2. “As far as I’m concerned,” says Andre Gietl, however “anything above three isn’t great. And in that building, it should have been possible to do better.”

Sun tubes bring daylight into the corridors and reduce the dependency on electrical lighting. However, the sun tubes in the suites may have undermined the building’s air-tightness to a degree

One of the two arrays of solar panels taking full advantage of the low-pitched roof’s southerly aspect

“The complication was really in lining up the various trades in a way that made sense in particular regard to the air-tightness. For example, they started building metal frame partition walls before they had installed the air-tightness, so to some extent we had to retrace some steps and remove the plasterboard sheets again, to gain access to the areas that needed to be sealed. That was a bit of a complication but the contractor was accommodating in taking a couple of steps back before they could move forward again.”

Gietl also singles out the sun tubes as particularly troublesome. “My point there would be that, same as with attic hatches and windows, the manufacturers should come up with the quality that’s required rather than builders onsite coming up with solutions that make the product air-tight. Your window is up to date nowadays in terms of sealing strips, but those tubes, certainly air-tightness was not one of the considerations in their manufacture.” The vapour check used in the building is Intello plus, together with the proprietorial glues and tapes needed to affix the membrane. Ecological Building Systems also supplied Panelvent exterior sheathing board, a medium density wood fibre board used as a substitute for OSB. “It’s got a couple of major advantages over OSB.” says Gietl. “It contains a minute amount of chemical glues, and therefore allows the board to breathe, to allow a certain amount of moisture through to the outside of a building.”

Solitex WA breather membrane and Panelvent sheathing board, all of which were supplied by Ecological BuildingSystems, during construction

Up on top, the 790m2 Bauder sedum roof, which was first used by MCO in Mater Orchard embodies a range of environmental and financial positives. Green roofs retain rainwater by storing it in the plants and substrate, which then evaporates back into the atmosphere. By slowing down and reducing the levels of rainwater entering the drainage system, less strain is put on sewage systems, thus helping to mitigate flooding. A green roof will retain 40%-90% of average rainfall, depending on the time of year. There are also sound reduction qualities, while natural colonisation and cross-fertilisation of plants allows a natural habitat to form. The roof is generally self sustaining and requires minimal maintenance. One of the key benefits however lies in the fact that it protects the waterproofing underneath from UV damage, thermal movement and weathering generally, thereby dramatically prolonging its life when compared with conventional roofing systems.

A rainwater harvesting system provided by Envirocare in Newry supplies all the water needed for flushing toilets. Rainfall is collected from the roofs and is then conducted through a Downstream Defender – a sophisticated silt trap – into the water tank, buried in the private garden at the rear of the building. Graham Donne of consulting engineers Delap & Waller explains why the team opted for rainwater harvesting. “We had twenty-two individual bedrooms, each with a WC, and then with the visitors and staff toilets there was quite a high demand for water for simply flushing toilets. A huge percentage of chlorinated mains water is flushed down the toilet. Rainwater harvesting was included to make a saving on that. The water is pumped from the tank up to a gravity fed tank at roof level, and all of the WCs are piped individually from gravity, so the only electricity used is to get the water from the rainwater tank in the ground up to roof level. Normally, you would have all water services boosted, so there’s a saving there on pumping power.” Does the sedum roof have any impact on how the water is collected? “It doesn’t take a huge amount of water,” says foreman Barry Murphy. “It’s only half an inch thick. It’s only on that long tropical Limerick summer, and you get your first rainstorm, you lose the first couple of hundred gallons on the roof, but it does make its way down eventually.”

Space heating comes from a 100kW Heizomat wood pellet boiler, which has an efficiency rating of 90%. This is augur fed from an adjoining pellet silo, into which pellets are blown by the delivery vehicle. The pellet boiler is backed up by a Remeha Quinta 85 condensing gas boiler supplied By Eurogas. A modulating boiler, it is Sedbuk A rated and has an efficiency rating of 98%.

The Intello vapour check

Two arrays of solar panels take full advantage of the low-pitched roof’s southerly aspect. 30m2 of Veismann Vito Sol 200 direct flow evacuated tubes are mounted on two A frames. Stephen Browne of suppliers Precision Heating says that a TSol calculation assuming 2650L per day at 60 degrees with a system efficiency of 60% should yield 35% of the occupants’ annual hot water needs.

Grahame Donne explains that the gas boiler will be called upon when the wood pellet boiler is down for maintenance. “We also have the gas fired boiler set to cycle on for half an hour a week so that it doesn’t go down on us for lack of use throughout the year. We have dual cylinders on the solar collector system, so the solar collectors are piped to a preheat cylinder which preheats the cold feeds into a primary domestic hot water vessel and then distributes that water throughout the building to thermostatic mixing valves at all wash-hand basins, baths, showers and so on.” While these integrations embody a high degree of automation, a Cylon building management system, supplied by McCool Controls & Engineering Ltd in Cork monitors their operation. The system also monitors and controls internal temperatures, while also monitoring the functioning of the rainwater harvesting system.

Pilkington K glass with an argon fill and a low emissivity coating was extensively specified to give a glass U-value of 1.2 W/m2K

Heat is delivered via a combination of Verco trench heaters in common areas and Merriott low surface temperature radiators in the bedrooms. One of the key reasons for choosing the Merriott LST rads – also used in Mater Orchard – is that they are easy to control. Throughout the building, the design team tried to ensure that the occupants were faced with a minimum of control options. To that end, and to achieve layouts most appropriate for assisted living, a nurse planner was called in to audit the design. “Given the age profile of the occupants,” says Grahame Donne, “all systems are very user friendly. It’s as simple as an on/off button, an indicator light to notify of a fault. All of the systems are set up on the main BMS, on time schedules which are to be set and agreed with the Sisters prior to occupation. After that, the system will run itself. They’ve got a very simple, straightforward control system that notifies of a fault and the system really just runs itself from morning til night.”

Apart from four external metal halide lamps, all of the lighting used is fluorescent or compact fluorescent, featuring fittings from Louis Poulsen, Thorn and Artimide. All internal lighting is switched, while photocells and timers are used on the external lights.

“Our brief,” says Philip Crowe, “was a private home. The solution was this subsidiary walled garden building that slips in behind these mature trees.” The experience gleaned from the Mater Orchard project gave the design team a vital working knowledge of a range of sustainable technologies, together with the confidence to work further innovations into future designs. “They’re quite similar. The things that the sisters found great about the Orchard – the privacy, the quiet, the fresh air, the healthy environment – all of that has been transferred here. Here though, we have a much better site, a much better orientation, and we’ve also looked more carefully at the wood we’ve used and avoided using hardwood windows. It’s a great development and a great step forward.”

Project details

Architect: MCO Architecture

Contractor: Brian McCarthy Contractors Limited

M&E engineer: Delap & Waller

Mechanical subcontractor: T Bourke

Structural engineer: Barrett Mahoney Consulting Engineers

Solar panels supplier: Precision Heating

Biomass boiler: Clearpower

Cedar window screens: Wood In Design

Cedar cladding: MTS

Supply air windows: Dwell-Vent / Howarths

Air-tightness products: Ecological Building Systems

Sedum roof: Bauder

Rainwater harvesting: Envirocare

BMS: McCool Controls & Engineering Ltd

Gas boiler: Eurogas

- Articles

- Design Approaches

- Force of Habit

- Mount Saint Vincent

- convent

- mater orchard

- supply air windows

- Trada

- Envirocare

- sedum roof

- Bauder

- solar panels

- biomass

- Clearpower

- rainwater harvesting

Related items

-

Solar panels to receive VAT drop in aim to boost uptake

Solar panels to receive VAT drop in aim to boost uptake -

Steeply sustainable - Low carbon passive design wonder on impossible Cork site

Steeply sustainable - Low carbon passive design wonder on impossible Cork site -

Focus on whole build systems, not products - NBT

Focus on whole build systems, not products - NBT -

International - Issue 29

International - Issue 29 -

Passive Wexford bungalow with a hint of the exotic

Passive Wexford bungalow with a hint of the exotic -

The House of Tomorrow, 1933

The House of Tomorrow, 1933 -

1948: The Dover Sun House

1948: The Dover Sun House -

The dazzling Dalkey home with a hidden agenda

The dazzling Dalkey home with a hidden agenda -

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather -

A1 passive house overcomes tight Cork City site

A1 passive house overcomes tight Cork City site -

Norfolk straw-bale cottage aims for passive

Norfolk straw-bale cottage aims for passive -

Time to move beyond the architecture of the oil age

Time to move beyond the architecture of the oil age