- Design Approaches

- Posted

Inner Space

An increasing number of sustainable homes are being built in Ireland but many of them are in rural areas, and yet, Ireland is an increasingly urban society. Jason Walsh looks at one recent attempt to renovate a small terraced house in inner-city Dublin, bringing it up to modern environmental and energy efficiency standards.

Behind the unassuming front door of an end terrace house in Dublin's Liberties' district lies a surprising experiment in eco-friendly and energy efficient living. This little red house is the home of architect Brian O'Brien, originally built in 1880, and has been carefully renovated in 2006 in order to make it as energy efficient and modern as possible.

Through this house O'Brien, perhaps best known as the architect behind the sustainability driven intentional community 'The Village' in Cloughjordan, expresses a clear desire to put his money where his mouth is. His practice, Solearth Ecological Architecture, founded in 1998, has already attained a reputation for providing beautiful high performance, low impact solutions to architectural, planning and process problems.

Working on his own house, however, has been something of a unique experience for O'Brien: "We do one off houses and house extensions but it's a small proportion of our work. We're currently doing some social housing in Ballymun," he says.

With a total floor space of just under 79 sq. metres (850 sq. ft.) O'Brien's house is not a palace but, then again, he might well argue that an oversized house is an unlikely candidate for sustainable status. Of the total 79 sq. metres, 12 sq. metres is composed of a new extension and the rest is the original Victorian building.

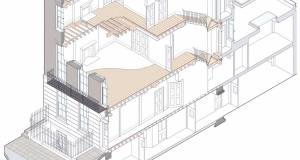

O'Brien's intention was to take this small, traditional blockwork building and re-imagine it as not only an energy efficient dwelling, but a contemporary open-plan living space: "I wanted a clean, modern space. I reduced the floor level on the first floor to increase ceiling height," he says.

O'Brien has maximised the sense of space through careful design: "You can always see into an area with a higher ceiling height."

Additionally, the focus of the house has been shifted upstairs, moving the kitchen and living area to the first floor and transforming the ground floor into a convertible work area and guest bedroom. The kitchen lies to the rear in the small extension and despite the presence of a split-level with the main living area in the original house the two 'rooms' have a unified and spacious feel. O'Brien explains his rationale as being purely practical: "Any of the work I'm aware of in these kinds of houses, I know intuitively that the best living is on the first floor." The main bedroom is located in the converted attic.

Obviously this strategy makes the house more comfortable - a large living area has replaced a collection of what must have been small, dark and dingy rooms, but there is an energy benefit to this reconfiguration. By maximising internal light and minimising walls and other structures that block it, O'Brien has managed to make the most of the sun in terms of both light and passive solar heat.

"The big challenge was getting light in from the south," he explains.

The ground floor space consists of the hallway, a scullery, bathroom and the guest bedroom and office, for which use can be modified by way of a moveable wall-cum-partition. Moving the wall, a simple folding affair (fig. 1 /p.65), changes the bathroom from standalone to en-suite status and envelopes part of the hallway, effectively co-opting it into the guest bedroom - an ingenuous use of space.

O'Brien's strategy called for maximising natural light in all areas of the house, including in the attic conversion

Material wealth

O'Brien also paid careful attention to materials when designing and specifying for the house. For example, his bannister, having been constructed from reclaimed bamboo, is an example of practical and low energy recycling.

Of course, not all additions to the house can be constructed from salvaged material. Nevertheless, he was careful to consider the social and economic costs of his building materials: "The window frames are European cedar rather than laminate or tropical hardwoods," he says.

The very fabric of the building was also problematic for O'Brien and impacted significantly on his plans: "The original construction was 4 inch block and 4 inches of mass concrete. A building fabric consultant discovered that the lime pointing was replaced with concrete pointing. As a result the brickwork is in a bad way," he explains. "It also means there's no possibility of having a breathable wall."

A natural material was selected for insulation: "I used Ecological Building Systems' hemp insulation and it's up to a reasonable u-value, but no more," he says, highlighting the difficulty of working with an older structure.

The option O'Brien settled for resulted in his bringing the building up to the standard of contemporary building regulations and then making use of carbon neutral space and water heating: "I put in renewable heating-a wood pellet boiler," he says. "This past winter I've used a tonne and a half of pellets and even in a conservation area I got planning permission for a flat plate solar panel."

Although it is too early to tell how efficient the solar is proving to be, the wood pellet heating system is working, providing suitable heat and hot water for the dwelling.

In fact, the wood pellet boiler, provided by NPS, is actually a stove-in that it provides both central heating and hot water. Due to space restrictions a larger wood pellet system was not a practical option, the result of which is that O'Brien cannot buy or store the pellets in bulk taking advantage of economies of scale and must pay more for smaller bags. Again we see sacrifices made due to the nature of the original building.

The ground floor hallway (left) with stairs leading to the main living area on the first floor. Bannisters are made from reclaimed bamboo; the main bedroom (right) is located in the converted attic

Nevertheless, O'Brien was certain that he wanted to progress in terms of sustainability: "We were very determined that everything would be as ecological as possible," he says.

Does this drive throw up difficulties for O'Brien? "It certainly makes it more satisfying, frustrating and challenging - particularly financially challenging."

Despite this, O'Brien sees this challenge as central to the nature of architecture itself: "We tend to take on projects as champions but the aim of the game is to bring architectural quality in terms of design and sustainability."

Indeed, O'Brien's commitment to sustainability did not make this renovation easy. Far from it, it in fact posed serious challenges. The fact that O'Brien is a practising architect obviously made things easier for him, particularly when it comes to specifying materials and developing strategies to deal with the existing structure, but the project was no cakewalk.

The construction company that O'Brien contracted for the renovation was Oikos Builders Ltd., for whom the job was a new challenge: "We hadn't worked with Brian before but we do some work for Grafton Architects and they know him. This was our first foray into this market," says Oikos' David Coyne.

Although a challenging project, Coyne does not feel that the working methodology applied to O'Brien's house had a significant effect on the difficulty of construction: "It was not hugely different but usually people are more worried about how a building looks than how it gets built," he said. "Brian was less concerned with clean modern design and more with technical issues."

Still, the nature of the materials used in the project does differ from those used in more traditional building: "A lot of the stuff we do is concrete whereas Brian is trying to get away from concrete - as well as PVC and concrete blocks - where possible. It was a different focus on the project."

One issue, if not quite conflict, that did arise during construction was a difference of opinion on insulation. O'Brien wanted to use a natural, hemp-based insulation product, whereas Coyne felt that more conventional insulation would yield greater benefits.

A combination of open-plan living and natural light give the space a clean, modern and surprisingly spacious feel ; even single floors in the house are divided into multiple levels (right) to add to the feeling of space

Coyne explains: "Kingspan is our normal product, the board, foil-backed foam which provides maximum insulation. According to Brian it's not the most sustainable product. For a start, it's an oil based industry.

"The hemp is lovely stuff to use but you need more depth, more thickness, to get an equal u-value," says Coyne.

Therein lies the central problem: O'Brien was faced with the question of which is preferable, a natural material that will, due to the space constraints of the pre-existing building, provide relatively poorer insulation or a modern material which will provide superior insulation but comes complete with a larger embodied energy quotient and, all-important for O'Brien, carbon footprint.

Significantly increasing the width of the walls to accommodate more insulation would have had the effect of introducing claustrophobia into an already small dwelling; the walls would seem to have closed in around the occupants.

Coyne says that O'Brien's commitment to sustainability meant that there was little chance of him using a material he is not convinced about: "He doesn't like the stuff, so hemp it was."

Coyne believes that the energy saved over the building's lifespan would more than mitigate the embodied energy in the insulation product. Despite this, the hemp insulation does bring the building up to modern standards and is an improvement on the building's performance prior to the renovation.

In fact, this dichotomy can be seen as an avatar for the contradictions internal to the entire build. Nevertheless, it's an issue that O'Brien clearly has no intention of shying away from. The limitations set down by the building's size and original construction do not mean that sustainability cannot be a goal, but they do have an effect on its implementation.

For O'Brien the issue of location is a central one and he argues that further suburbanisation is not conducive to sustainability and so urban solutions are required: "Sustainability in the city - the cost of construction is pushing people out to the suburbs and farther afield," he says. "Good design is always about sustainability because it makes a renovation as interesting as a new house. It adds value."

So when it comes to achieving sustainability in the city, does O'Brien favour renovation or new building?

"It's case specific," he says. "I wouldn't like to generalise. Heritage enthusiasts would like to talk about the embodied energy that has already been paid off over the life of a building. I don't think that's always true. At least seventy per cent of my building is new - that's a lot of intervention to get it up to modern standards."

Transmission of natural light and creation of space is also achieved by creating an "open" stair without risers between steps

Similarly O'Brien, though clearly in favour of natural materials, does not harbour an anti-technological bent: "There's always a need for technology. As architects we're trying to integrate it into the design," he says.

For the 12 sq. metre extension, O'Brien selected T9 version of the Poroton clay blocks, supplied by wexford based FBT. David Coyne describes Poroton blocks thusly: "They're a clay brick with a honeycomb structure inside. This is filled with vermiculite to increase insulation," he says. "You can build a solid wall with the same u-value as a cavity wall but there's no cement content, cement has a pretty heavy carbon footprint."

Coyne is clearly impressed with the blocks but does raise some questions about how easy it will be to persuade some clients to use them: "It's easy to sell something with greater insulation but saying 'less cement' is a harder sell," he says.

The construction work took a total of six months, an average length for a job on that scale according to Coyne: "We went in and stripped it down. I don't think being green slowed it down, renovation work is just slow."

He also points to the relatively complex nature of the project: "Brian has squeezed three floors into a two floor house.

"We attempted to seal the house and we got infiltration down to the level you'd expect with a new house, despite it being an old house," Coyne says. "We dry lined the inside of the walls and extended the wall widths slightly to get a bit more insulation in."

Clay components were also used for drains, in preference to PVC and trickle vents were added to the windows for ventilation.

Internally O'Brien also sought to reduce environmental impact, using natural paints and woodstain. "I used Auro paints for the walls and a water-based wood protector for all of the woodwork," he says. "At the selfish end it's health and toxicity levels [that drove that decision] but at the other end it's the green credentials."

Bodo Bodewigs of Sligo-based Healthbuild, supplier of Auro products in Ireland claims that natural paints offer significant health and environmental benefits: "Many paints have an unnatural molecular structure, synthetic solvents that have been deodourised. Natural material with an unadulterated molecular structure is what your body can handle. Even if you take it in through the skin, the body will pass it out in a few days," he says. = Additionally Auro products are certified as having a carbon-free manufacturing process, claiming a positive energy balance through offsetting.

According to Bodewigs natural paints can be used in any situation: "Any problem you face with the Irish climate can be dealt with using natural material. I have no hesitation in saying that."

Knowing how to do the job properly is of paramount importance: "Of course, we have a variety of moulds in this country and we come across it because we're dealing with wood. I've seen situations where people didn't apply enough of our wood preservative and a few had problems later."

Auro's wood treatments, however, are well up to the job and certified to the EN927 standards demanded by window manufacturers. "We don't compromise with petrochemicals and we still get high ratings," he says.

A wood pellet stove provides space and water heating for the entire dwelling

Bodewigs goes further than simply promoting natural paints and wood treatment products, however. He sees the preference for some materials as a partial indictment of Irish building standards: "Use of fungicides in indoor materials reflects bad building practices - manufacturers don't trust the standard of the builders," he says. "Fungicides are 'biocides' - they effect the environment."

David Coyne from Oikos says that the experience of working with O'Brien was an interesting one and that it could influence the company's future work: "We're having a look at it. It was a bit of an educational process for us and we've been talking to an architect and engineer about using the Poroton blocks for a house in Blackrock. You need the client with the appetite for it."

Contrary to its status as a renovation and in spite of the limitations brought about by the old building, O'Brien's house did involve major building work - and costs: "Effectively I built a new house, having bought a house."

No-one is attempting to claim that renovating a small, inner-city house is easy and no-one would claim that O'Brien's house is the world's most sustainable but given the parameters in which he was working, O'Brien has done a remarkable thing in giving this Victorian end-terrace a new lease of life as a healthy, eco-friendly energy efficient home.

"He's had to make compromises, but he's made them from his perspective," says David Coyne.

Ultimately though for O'Brien it seems to have been worth it. The house points toward a future of energy efficient city living and at the same time holds out a hand toward the conservation and preservation of historically significant buildings. This is unsurprising when the architect's motives are concerned: for O'Brien a building is a unique piece of engineering, something that is reflected in his desire for sustainability: "I think it's important to think about the metabolism of the building - throughput of power, heat, water. A bridge doesn't have that." Clearly the human factor has prevailed.

Selected project team members:

Architect: Solearth Ecological Architecture

Building contractor: Oikos Builders

Poroton blocks: FBT

Insulation: Ecological Building Systems

Natural paint: Health Build

Wood pellet boiler: NPS

Solar: Solaris

- Articles

- Design Approaches

- Inner Space

- conservation

- liberties

- inner city

- housing

- restoration

- architect

- energy efficient

- hemp insulation

Related items

-

Steeply sustainable - Low carbon passive design wonder on impossible Cork site

Steeply sustainable - Low carbon passive design wonder on impossible Cork site -

Focus on whole build systems, not products - NBT

Focus on whole build systems, not products - NBT -

International - Issue 29

International - Issue 29 -

Phase one complete at UK’s largest passive scheme

Phase one complete at UK’s largest passive scheme -

Passive Wexford bungalow with a hint of the exotic

Passive Wexford bungalow with a hint of the exotic -

The House of Tomorrow, 1933

The House of Tomorrow, 1933 -

Historic London house gets near passive transformation

Historic London house gets near passive transformation -

1948: The Dover Sun House

1948: The Dover Sun House -

The dazzling Dalkey home with a hidden agenda

The dazzling Dalkey home with a hidden agenda -

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather -

A1 passive house overcomes tight Cork City site

A1 passive house overcomes tight Cork City site -

Leicester cathedral to get passive extension

Leicester cathedral to get passive extension