- Economy

- Posted

On the money

Every eurozone government has debt problems and is cutting its spending, Richard Douthwaite says. Defaults and a prolonged depression are inevitable unless countries inject money into their economies in an unconventional way. A prosperous low-carbon economy would be the result

As so often happens, decisions which will affect the lives of billions of people and the future of our civilisation are being taken without any public debate. Moreover, because wide-ranging discussions are not going on, those taking the decisions are doing so in ignorance of important constraints and most of their more radical options.

Over the past two years, Ireland has seen the dire results of a decision taken in ignorance of all the options. On the evening of September 28th, 2008, Brian Cowen and Brian Lenihan genuinely believed that they had no alternative but to guarantee the banks because their continued operation was vital to the Irish economy. A review of possible conventional strategies prepared over the previous five days by Merrill Lynch had said that no bank should fail and a guarantee would be best for market confidence. More radical strategies were ignored. The result, as we know, was to make the state responsible for debts so large that their total is beyond the ability of the economy to support.

Ever since then, the government has been trying to get the banks to resume lending. Graph 1 shows how totally unsuccessful the effort has been – more loans are being repaid than new ones taken out. No one in government has admitted that it is unreasonable to expect the banks to do anything more than a token amount of lending at present because their customers' earnings are shrinking, increasing the burden of their existing debts and reducing their ability to repay any new ones. On average, Irish residents' incomes have fallen by 19% since their peak in the final quarter of 2007 and the first quarter of this year. They will fall further as the government's spending cuts come into effect, especially after the €3 billion that we are told will be axed by the budget at the end of the year.

Graph 1: This graph, prepared by the Central Bank, shows that the total amount being lent to households by Irish-based financial institutions has been falling since June 2009 and the amount being lent to companies since last December.

The spending cuts are also being made because the government does not know of any alternative. As Mr Lenihan has told the country repeatedly, foreign lenders cannot be expected to continue to provide funds to a government that is making no effort to bring its spending and income into balance. Last autumn, he said that the cuts proposed by An Bord Snip Nua would be "a picnic" compared with those the government would have to implement. If borrowing continued unchecked, he added, then by 2013, €2 out of every €3 of income tax would have to go to service a national debt of €160bn.

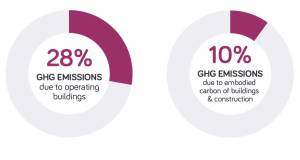

The governments of most other rich countries are cutting their spending too. In the eurozone, for example, every single country has a budget deficit greater than the 3% limit imposed by the Maastricht Treaty, as graph 2 shows. Even the German government has announced that it will use tax rises and spending cuts to reduce its deficit by €80 billion, despite the fact that 3.15 million people are out of work and its economy has a lot of spare capacity. In Britain, the coalition government has asked departments to prepare proposals for cuts of an astounding 40% and a new, independent government agency, the Office for Budget Responsibility, has forecast that 610,000 public sector jobs, 11%, will be axed over the next six years.

Graph 2: Every government in the eurozone is running a budget deficit bigger than that allowed under the Maastricht Treaty.

Source: Der Spiegel

Now while it might make sense for a single country to cut its spending to get its income into line with its spending, it makes absolutely no sense for every rich country to try to do so at the same time. Yet this is exactly what was agreed at the G-20 meeting in Toronto at the end of June, during which the advanced economies undertook to cut their deficits by at least half by 2013 and to stabilise their debt-to-output ratios by 2016. To compound their folly, the governments also said that they would set higher capital requirements for their banks to ensure that, in future, they could withstand financial shocks without state support. The effect of this will be to prevent the banks increasing their lending until they have made enough profits to raise their capital to meet the new requirements.

Many economists have warned that these policies will lead to a 1930s-style depression. In Italy, 100 economists signed a letter to a newspaper saying that the EU's ‘politics of sacrifice’ risked accentuating the debt crisis by causing a faster rise in the rate at which jobs were being lost and in the number of insolvencies and company failures. Some countries could be forced to leave the monetary union, they said.

The Nobel Memorial prize winner, Paul Krugman, wrote in The New York Times at the end of June that the world was in the early stages of a depression. "The cost — to the world economy and, above all, to the millions of lives blighted by the absence of jobs — will ... be immense" he wrote. "[It] will be primarily a failure of policy. Governments are ...preaching the need for belt-tightening when the real problem is inadequate spending."

Economist Paul Krugman advocates that the US government should continue to borrow until the economy picks up

My favourite economic journalist, Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of The Daily Telegraph, believes that a depression has already begun. "The US is still trapped in depression a full 18 months into zero interest rates, quantitative easing and fiscal stimulus. The budget deficit [is] above ten percent of GDP,” he wrote recently, pointing out that only 58.5% of America's working-age population now have jobs, down from 63% three years ago. This means that eight million jobs have been lost in that period, each a catastrophe in a country without an adequate system of social welfare.

A prolonged depression will not destroy our civilisation directly, but, if one happens, its consequences almost certainly will. I'll explain. Suppose the depression lasts for ten years. During that period, fossil energy prices would be low because demand would be suppressed. This is likely to remove any price incentive for a move to non-fossil fuel sources. In any case, even if a project's profitability looked good, the banks would be doing very little lending and it would be very hard to raise the capital to carry it out.

So the depression would be ten wasted years as far as the phasing-out of fossil fuels is concerned. This is where the threat to the continuation of our civilisation lies. Every reader of Construct Ireland knows that the Earth's supply of fossil fuels is finite and that humanity is rapidly depleting the usable part of the resource.

I wrote “usable" advisedly as there's a still a lot of fossil fuel underground. The problem is that it takes energy to get it out and the amount required is increasing. This is because energy companies naturally exploit the easiest resources first – the thickest coal seams and the shallowest onshore deposits of gas and oil. It's only after the best resources have been used that they move on to the trickier ones – the thinner coal seams plagued with geological faults, or the oil and gas fields under the Arctic ice or in deep water offshore.

These more difficult resources require much more capital investment and have higher running costs. In other words, more energy has to be invested and spent to release the energy they contain. So, while it took the energy in one barrel of oil to produce a hundred times that amount of energy in Texas in the 1930s, that same energy investment produces only 15 barrels of oil today. It's the same with iron and other types of ore too – poorer deposits are having to be mined and it takes more energy to concentrate the good bits from them. As a result, while the depression grinds on, increasing amounts of energy are going to be required to produce the world's energy and mineral requirements.

When an energy resource gives, say, ten times more energy back than it took to extract it, 90% of the energy it contains is available for human use. However, when the figure drops to 5 to 1, only 80% is available, and after that, a rapidly-rising proportion of the energy in the resource has to be used to produce it. At 3 to 1, for example, only two-thirds is available.

Now you could say that it would be worth producing oil for energy use so long as you got back slightly more energy in oil than it took you to u extract it. However, that would mean that the economy devoted almost all its efforts to getting its oil and had almost no energy left for doing anything else. Professor Charles Hall of New York State University, who developed the energy-return-on-energy-invested (EROEI) idea after investigating why fish bothered to use energy to migrate, believes that, in view of the amount of energy it takes to run a civilisation, its energy sources have to have an average return significantly higher than 3:1 for it to persist.

Chris Vernon, one of the editors of the Oil Drum website, says that although there might be enough oil for global production to be approximately half today's level by 2050, how much usable energy humanity will get from that depends on the rate at which the EROEI declines. If the EROEI declines faster than it did in the US during the 20th century, he says that it is possible that in forty years' time oil will cease to be a significant net energy source. Exactly the same argument applies to the net amount of energy available from coal and gas.

Consequently, if a prolonged depression is allowed to happen, much less renewable energy is likely to be available for humanity's use when the energy cost of fossil fuels rises so high that it's not worth carrying on production. The depression would not just waste ten of the forty years of fossil fuel use we might have left, but the ten best years, the years with the highest net energy return during which it would be possible to devote more energy to the switch to renewables than in any decade later on.

The defining characteristic of our civilisation is its high level of energy use and the complexity that that has enabled us to achieve. Without a lot of energy, our systems of production and distribution will break down, and it will become impossible to feed, clothe and house the nine billion people the world is expected to have by 2050. A depression will not only blight millions of people's lives now, but condemn billions to death later on.

So what is to be done? What solutions are the decision-makers either rejecting or overlooking? It is easy to understand why they find Krugman's solution unattractive – he just advocates that the US government should continue to borrow until its economy picks up. "US government bonds continue to find ready buyers, even at historically low interest rates. The long-run budget outlook is problematic, but short-term deficits aren’t — and even the long-term outlook is much less frightening than the public is being led to believe" he wrote in February. His opponents point out that US public sector debt is already about 94% of GDP and it would become unmanageable if it went any higher. So no remedy there.

The Italian economists follow Krugman's line. They want the European Central Bank to use the technique known as "quantitative easing" to create money out of nothing to lend to eurozone governments for them to spend. The trouble with this is that the national debts of the countries concerned would continue to increase.

Italian economists want the European Central Bank to create money to lend to eurozone governments for them to spend

Krugman's and the Italians' proposals are both based on the belief that the current crisis is a temporary blip and that the world economy will begin to grow again, generating the incomes to support the higher level of debt. My solution is different because it starts from the position that the world is entering a new era in which continuous growth will be impossible as there won't be the energy for it. Indeed, it is far more likely that, given the increasing energy cost of producing energy, the world economy will begin to shrink. As a result, continuing to issue money as a debt will cease to work because neither would-be borrowers nor prospective lenders will have the confidence that it will be possible to pay the interest on the sums involved, whatever about paying back the sums themselves. In that case, without the prospect of future growth to dilute them, both public and private sector debts are already too high. Countries where firms, people and governments are already having problems servicing the debts they have should simply refuse to borrow any more. Another solution needs to be found.

If the global banking system is to be saved, incomes need to rise to enable borrowers to honour their current commitments. Economic growth is not the solution. Even if countries could bring it about by reversing their deflationary policies, the expansion would quickly create energy shortages. Fuel prices would rise and, in effect, tax away some or all of the growth-produced income so that it was not available to help service current debts and to support current asset values. Moreover, even if that was not the case, the growth would take several years to raise incomes by enough to make the present debt- and asset-burden supportable and, unless it was generated by investments u in the transition to an ultra low-carbon economy, it would mean that less energy was available for that transition.

The only way that we can raise incomes quickly without any energy use is by organising an inflation. This cannot be carried out with borrowed money, of course, since that would increase debt and the lenders would impose an interest rate equal to the rate of inflation they were expecting. The money required has to be issued debt-free.

In the eurozone this could mean that, every quarter, the ECB gave money created by quantitative easing to governments in proportion to their populations. No debt would be involved. The governments would spend part of the euros they received themselves or use them to pay off their debts. They would give the balance to their people because private indebtedness needs to be reduced too. Everyone would get the same amount but companies would be excluded.

The recipients would be required to pay off all their debts before spending any of the money they received. If someone was not in debt, they would get their money anyway as compensation for the loss that the inflation would cause to the real value of their money-denominated savings. Without this, the scheme would be very unpopular. The ECB could issue new money in this way until the eurozone's overall debt, public and private, had been brought sufficiently down for employment to be restored to a satisfactory level.

The former Green Party senator, Deirdre de Burca, has improved on this idea. She points out that (1) we don't want to restore the economy that has just crashed and (2) that politicians don't like giving away money for nothing. Her suggestion is that the money given to ordinary citizens should not just be lodged in their bank accounts, but should be sent to them as special credits which could only be used either to pay off debt or, if all their debts were cleared, to be invested in projects linked to the achievement of an ultra-low-carbon Europe. These could range from improving the energy-efficiency of one's house to investing in an offshore wind farm or a community district heating system.

Former Green Party senator Deirdre de Burca

A common argument against using inflation to reduce debts is bound to be trotted out in response to this idea. It is that, if an inflation is expected, lenders simply increase their interest rates by the amount they expect their money to fall in value during the period of the loan, thus preventing the inflation reducing the debt burden. However, the argument assumes that new loans would still be needed to the same extent once the debt-free money creation process had started. I think that is incorrect. Less lending would be needed, the investors' bargaining position would be very weak and interest rates should stay down. Incomes, on the other hand, would rise. As a result, if the debtors continued to devote the same proportion of their incomes to paying off any new or remaining loans, they would be free of debt much more quickly.

Despite the fact that Ben Bernanke, the chairman of the US Federal Reserve, made a speech in 2002 – before his appointment – in which he said that, if ever there was problem with a lack of demand, money could always be distributed by being thrown out of helicopters, the chances of getting this proposal adopted seem vanishingly small. For one thing, it sounds too good to be true. Can it really be that we don't have to flagellate ourselves for overspending and that we can just pay off our debts and get free money instead? Another irrational obstacle is the German folk memory of the hyper-inflation immediately after the First World War. A German ECB executive board member, Juergen Stark, said in May that his bank would resist any pressure to allow higher inflation. "On the ECB board, we are a very convinced band which will resist political pressure," he told Deutschlandfunk Radio.

But would anyone lose if governments gave away money so people could pay down their debts? The extra money would reduce the euro's exchange rate, of course, restoring some of the competitiveness the eurozone has lost since a euro was worth less than a dollar. Imports would fall as they became more expensive while exports would rise. This would boost manufacturers' order books. Employment u would increase, too.

For some months, the extra euros' effect on wages and prices would be limited as there is a lot of unemployment and spare industrial capacity about. However, the extra demand would eventually cause an inflation by raising wages, making it easier for people to service their remaining debts. Moreover, the normal objection to inflation would not apply because savers would have already been compensated for its effects by the money they had been given.

Businesses would also be helped because the inflation would lower their debt burden in terms of the prices they could charge. Banks would find that they had more deposits, fewer bad debts and could do without state support. Governments would have additional tax revenue, reduced social welfare costs and lower interest bills because of their lower debts.

On the other hand, if we confine the range of options we consider to those based on the assumption that growth will soon resume and that assumption proves misplaced, not only will the human consequences be disastrous, but the financial ones will be too. As incomes shrink as a result of the G-20's co-ordinated austerity measures, the prices of property, shares and other assets will fall too, reducing private pensions and plunging more people into negative equity. Investment will stop, tax revenues fall and unemployment levels will rise so much that benefit rates will have to be cut. Eventually, governments will be unable to borrow any more and will default. I can't identify any group that would benefit from this scenario. Even the mega-rich would see their wealth massively reduced.

In 1942, at the height of World War II, great sacrifices were required. The employment rate was “overfull” and the US was devoting 40% of its national income to the war effort, Britain 43%, the USSR 66% and Germany 52%. I believe that, today, we need to be diverting resources on a similar scale to reducing fossil energy use and slowing climate change. Instead, this country has diverted the 19% of its annual income it has already lost to defending a method of money creation that no longer suits anyone's interests. And, as the government tells us, we must prepare to sacrifice an even larger amount annually for the next few years.

If all the monetary options were presented and thoroughly discussed, the public would deliver a decisive “No” to the current strategy. It would say that, while it would be prepared to accept a “politics of sacrifice” to prevent energy shortages and widespread starvation within the next fifty years, there was no question of it accepting one to preserve a debt-based way of distributing money.

Yet how many people are aware that there are other ways of putting money into use? Our politicians certainly aren't and parrot Mrs Thatcher's line: “There is no alternative.” Somehow, this ignorance has to be eliminated. Destroying a callous and unthinking monetary orthodoxy is the supreme challenge of our age. A much brighter future would open before us if it were gone.

- Articles

- economy

- On the money

- douthwaite

- Lenihan

- NAMA

- recession

- Bail

- Cuts

- budget deficit

- quantitive

- easing

- fossil fuels

- energy

Related items

-

Green shoots for green building

Green shoots for green building -

The world energy crisis 2022

The world energy crisis 2022 -

Grant invests in biofuel tech for oil boilers

Grant invests in biofuel tech for oil boilers -

Oil heating sector pivots to biofuels, but green groups raise concern

Oil heating sector pivots to biofuels, but green groups raise concern -

Architects call for urgent climate action ahead of COP 26

Architects call for urgent climate action ahead of COP 26 -

Grant heat pumps at centre of NI energy transition project

Grant heat pumps at centre of NI energy transition project -

Green groups critical of latest budget

Green groups critical of latest budget -

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries -

Passive house costs falling, new study finds

Passive house costs falling, new study finds -

The Jodrell Bank grand challenge

The Jodrell Bank grand challenge -

Reaching for the first rung

Reaching for the first rung -

New research finds air pollution particles in human placentas

New research finds air pollution particles in human placentas