- Economy

- Posted

Steep decline

The world has learned the hard way that our political leaders lacked the judgement and resolve to identify and address the problems which led to the recession. Richard Douthwaite argues that a similarly flawed judgement is evident in the assumption that the economy will recover, and advises on how to prepare for a future of global economic contraction.

In at least two speeches during the local and European election campaign, the Taoiseach, Brian Cowen, said that economic recovery was in sight and that Ireland was positioned to return to growth next year. The governor of the Central Bank, John Hurley, was more guarded when he spoke on RTE in early June. He warned that economic recovery would take time but he too expected it to start next year.

Both men were wrong. Very wrong. And the trouble with their optimism is that they misled the public and thus made it more difficult for people to make adequate plans for a future which will be very different from the one they have been conditioned throughout their lives to expect. If a recovery does begin it will be very short-lived, for reasons which I hope this article will make clear.

What Cowen and Hurley should have said is that the world in which long spells of rapid economic growth was possible has gone for ever. Instead, we are now in a world in which, apart from brief upturns, our incomes will decline every year. This changes everything. House prices will fall rather than rise. Debts will become unpayable and have to be written off. As a result, pension funds invested in property and bonds will disappear.

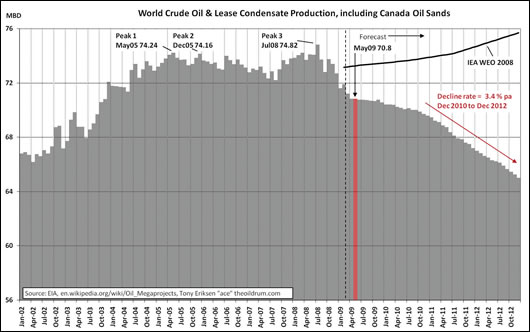

What brought the change about is that world oil production has peaked. As shown in illustration 1, it has already declined significantly from its maximum last year and, while it can retain its present level for a little while, some commentators expect output to begin to fall by around 3.4 per cent a year from the end of 2010. Even if they are wrong, it will never return to its 2008 level because, when oil prices dropped from their high of $147 a barrel last July to around a quarter of that level seven months later, oil and gas companies panicked and cut back spending on developing their fields.

CLICK IMAGE FOR LARGER VIEW: Illustration 1: World oil production peaked in July 2008 at 74.82 million barrels/day and now has fallen to about 71 mbd. It is expected that oil production will decline slowly until the end of next year as OPEC production increases while non-OPEC production declines. However, from the start of 2011, the decline rate could increase to 3.4% as OPEC production will probably be unable to offset the increasing pace of the non-OPEC production decline. The supply forecast in the International Energy Agency's World Energy Outlook 2008 is shown for comparison.

Source: http://www.theoildrum.com/files/ccst20090515.png

One result was that the number of rigs drilling for natural gas in the US was down to 685 this June compared with 1,600 last summer. Another was that in Russia, the world' s biggest gas producer is considering delaying investing to open its giant Bovanenkovo field for at least a year.

At the end of May, the International Energy Agency estimated that there had been a 21 per cent drop in oil and gas investment compared with the previous year. This means that the world has not fully replaced the oil and gas production capacity it has used up in the past twelve months. Future coal supplies will be lower too since that industry has also invested less.

Renewable energy projects have also been delayed by the downturn. In 2007, the waiting list for the delivery of a wind turbine was about three years. Things are quite different now and a few weeks ago, the biggest turbine manufacturer, Vestas, announced that it was closing a factory making the blades on the Isle of Wight. Similarly, the first of the two undersea electricity cables planned by Imera running from Ireland to Wales which was to have opened at the end of next year has been delayed by funding difficulties. This will slow the pace at which Irish windfarms can be developed.

If the “green shoots” of recovery that keep being mentioned actually do emerge and demand picks up appreciably, the delayed investments will mean that energy output will not be able to return to the level it reached last year and prices will soar. This will undermine the recovery in two ways. One is that it will take money out of consumers' pockets and send it off to the countries from which energy supplies come, thus curtailing domestic demand.

This was exactly what happened immediately before the sub-prime crisis broke out in the US. At that time, energy purchases had risen to the point at which they were taking 14 per cent of US national income. This squeezed amount left for other things including loan repayments and made it inevitable that the weakest borrowers would run into difficulties.

The second effect is that the higher energy prices will cause inflation. Central bankers, who are very alert to inflation risks at the moment because they are worried about the huge sums of money they have been creating out of nothing to pump into ailing economies, will increase interest rates sharply. This will not only push up business costs, reduce profits and impede the recovery, it will also cause severe problems to everyone, governments included, who are already struggling with massive debts.

Another banking crisis will develop and governments, including our own, will reach the point at which they are unable to borrow more and will default. Social welfare payments and public services will be cut drastically and unemployment will rise. Take-home incomes, already considerably reduced since July 2008 for those who have managed to retain their jobs, will fall much further.

The recession will become a depression. Energy prices will drop below the floor level they found in the early part of this year, and investment in bringing new fossil and renewable sources into production will fall again.

After a year or two of financial restructuring, another attempt at recovery may begin. If one does, energy demand will rise and the price of power will start increasing again but at a lower output level than before. This will choke the recovery off and energy prices will drop back down, halting energy sector investments almost entirely and bankrupting projects started by people who thought that scarcer energy was bound to put its price up.

Yamal Peninsula, which holds Russia's biggest natural gas reserves, and where the Bovanenkovo gas deposit is located

After this second cycle, the potential for recovery will be small since two important sources of investment funds - corporate profits and private savings - will have dried up and property prices will be so low that it will be barely acceptable as collateral. The Irish government's ability to borrow to invest will be limited because of the default.

Euros will get very scarce and, in desperation, new forms of currency will be introduced which, unlike the monies used today, do not depend for their existence on people's readiness to go into debt. However, while the new type of money will lubricate local and perhaps national trade, only the hard-to-find euros will be acceptable internationally.

Ireland will be forced to rely much more on its own resources. Since its export markets will be very weak, it will have limited ability to import fossil fuels and the equipment it needs to develop its renewable energy sources. Moreover, as happened after the collapse of Lehman Brothers, there will be problems with the letters-of-credit system which underlies a lot of foreign trade. Sellers will ask “Can we trust this Irish bank's guarantee that our account will be paid?”

Barter systems will emerge, just as they did in Russia when the rouble collapsed in the late 1990s. At that time, The New York Times carried a story which described how Splav, a company in Novgorod which made valves for the oil, gas, chemical and nuclear industries, managed to keep its 4,000-strong workforce busy with only 10 per cent of its invoices being paid in cash. The company even set up a chain of chemists shops to sell the drugs it received in payment from some customers. It paid its local taxes in Volga cars, road tax with excavators and medical insurance with ambulances.

A staff of fifty developed deals. One particularly complex one to finance a sale to the Balakovo nuclear power station involved the power company cancelling the overdue electricity bill of a foundry in Kazakhstan on the basis that the latter would send castings to a factory in the Russian republic of Bashkiriya, which then sent its product to the Lipetsk Metallurgical Combine, which then provided sheet metal for a half dozen car and truck factories = in Russia and Belarus. The vehicle manufacturers then sent cars and trucks to Splav, some of which it sold for cash. Others were used to pay some of its taxes. Splav had to mark up its prices to make the barter sales work because a lot of the goods it received had to be sold or exchanged at a discount.

As incomes fall, maintenance will be neglected, particularly as spares will get harder both to afford and to obtain. Breakdowns will become more frequent, so production and delivery will become less reliable. There are serious worries about how long it will be possible to maintain communications, co-ordination and control systems since computers and servers already consume 2 per cent of the world's energy, as much as aviation, and need additional energy for the manufacture of the replacements required every few years.

an Taoiseach, Brian Cowen TD, speaking at the CBI NI Annual Dinner 2009

Indeed, finding the energy and other resources to maintain buildings and the rest of our infrastructure will become increasingly difficult and a lot of our present stock will be abandoned after being stripped of anything of value. The sites will eventually return to forest, as there may not be the energy to clear the land for more intensive use. Suburbs in Flint, Michigan, are already being returned to nature, although there is still the energy to bulldoze the houses first.

Some property built during the Tiger years will never be used. Others, in bad locations, will be closed up quite soon. Estimates published by Ronan Lyons of Daft in February1 indicate that 200,000 too many houses were built between between 2002 and 2008. “We churned out over half a million properties, off an existing base of just 1.3 million households,” he writes. “An overview of economists’ figures suggests that we should have been building perhaps 300,000 households in that same period.” Many of these houses were in the wrong place. More houses were built in Connacht-Ulster than in Dublin, although the latter has almost twice the population, Lyons points out.

Standard and Poors puts the number of surplus houses even higher - at 250,000. Either figure has profound implications for the price that the National Asset Management Agency pays for the developments it is taking over from the banks. The properties and projects it will get are like ships blown ashore at the top of a high spring tide. The water is unlikely to rise high enough ever again to allow them to be floated off. The fact that the Swedish “bad bank” was able to sell off the properties it took over in the early 1990s is irrelevant as, back then, the global growth tide was still coming in.

The reason why the tide will never get high enough is that Ronan Lyons has calculated that the effective rate of interest on property loans was negative throughout the entire Celtic Tiger period. In other words, borrowers were being paid to invest. Now the effective rate is strongly positive because, although bank interest rates are low, property prices are falling and, if you add the percentage price fall to the interest cost, the “real” interest rate is around 14 per cent. If incomes are now on a long-run declining trend and take property prices down with them, as we must expect, the real interest rate on property purchases will continue to stay high and they will remain unattractive investments.

Vestas wind turbines at the Black Banks wind farm in Drumkeerin, County Leitrim

The scenario I've just sketched is only one of an infinite number of possible ways the future will unfold. We can, however, be fairly sure about the main features of the decline which has just begun. These are:

1. Less energy will be available than at present. The supply will decline year by year and its price will fluctuate widely according to the state of the global economy. This volatility will deter investment in developing new supplies.

2. Less energy means lower incomes, which will also fall year by year.

3. Inflation was a feature of the energy-fuelled upswing. Deflation or falling prices, will be a feature of the energy-scarce move down. Just as inflation lightened the interest rate burden on the way up, deflation will increase it on the way down.

4. Lower real incomes will make it more difficult to service debts. Massive defaults are inevitable and only the desperate will wish to borrow. No-one will wish to lend except at very high interest rates which compensate for the risk even though high rates make defaults more likely.

In fact, many of the positive feedbacks which made the upswing such an easy ride will go into reverse on the way down and aggravate the situation. Take economies of scale, for example. These lowered unit production costs while output was expanding, but the lack of scale will increase them on the way down.

So what should you do to respond to this new situation? Here are some suggestions.

1. If you have a large house, trade down to somewhere easier to maintain and heat, ideally with space for a vegetable garden. But don't rent a place to live because, although it might seem to make sense to let someone else carry the capital loss as property prices fall, at some time in the future you may not have the income to pay your landlord.

2. If there is a temporary recovery in the next month or so, take advantage of it to sell whatever assets you have apart from farm land. There will never be a better time to sell. If there's no recovery, sell anyway.

3. Use the asset-sale proceeds to get out of debt, as otherwise you or your company will have to pay loans off out of a smaller income.

4. Reduce business and personal overheads in every way you can. For example, stop paying for a pension – it won't deliver. If you have an endowment policy, cash it in.

If you have any money left after paying your debts, spend it so that, even if your purchases lose their money value slowly, you do at least get continuing benefits from owning them. If you put money into a bank or conventional investments, you may lose it all at once.

This lose-money-slowly approach was suggested by Dmitri Orlov when he spoke at Feasta's New Emergency conference in June. He based his remarks on observing the effects that the collapse of the USSR had in his native Russia. “We do have some control,” Orlov said. “Our financial assets may not be long for this world, but while we have them we can redeploy them to good long-term advantage.”

So how should they be redeployed? It would be nice to think that Ireland as a whole could mobilise its resources to provide a cushion in case hard landings lie ahead but that won't happen until opinion leaders stop claiming to have seen green shoots and imagine that life can go on as before. A majority of people needs to have recognised that an historic turning point has been passed and that contraction rather than growth is the order of the day before a national mobilisation will happen. Until then, anyone with money should concentrate on spending it in ways which provide their families and communities with the things that they will need if money and supply systems break down. Community-level food and energy production need to get top priority and, since they should no longer be funded by money debts, novel financing methods are needed.

Feasta has been discussing two such methods. One involves the issue of energy bonds. These would be promises to pay the bearer the cash value of, say, 1000kWh at the time the bond was presented for redemption. A community power company would sell bonds with differing maturity dates. Some would mature in three years' time, when its project had been operating for a year. Equal amounts of the remainder would mature each year after that, stretching out to year ten or twelve.

A boarded-up building in Flint, Michegan

These bonds would probably be sold by tender. They would be bought by people wanting a long- to medium-term investment who thought that the price of electricity was likely to rise over the next few years in comparison with other prices. Bidders would offer an amount they thought should give them a fair return for locking up their cash for the number of years they chose. (Of course, if they needed to get cash for their bonds before they matured, they could always sell them to another investor.)

The money paid for the bonds would be used to develop the power source and, when the bonds matured, the investors would be paid off out of the money that the energy users were paying that year for their power. In this way, the consumers would gradually take full ownership of their company's assets.

The bond approach can also be used to raise funds for non-energy investment. Indeed, Michael Layden, a Feasta member and wind-farm developer, has turned the concept into ‘aggressive mutuality’, a powerful way for consumers to take over the firms providing the goods and services they buy regularly so that, when they retire, they have also bought themselves a pension2.

The second novel financing technique, equity partnerships, was refined and developed by Chris Cook, a former director of the International Petroleum Exchange and the originator of the Iranian Oil Bourse. He described it in last year's Feasta lecture3. James Pike, the architect, has since taken the concept and shown how it can be used to re-structure distressed development projects.

The approach overcomes a serious problem with the standard capitalist company structure. The problem is that when an economy contracts, the fraction of the firm's income which ended up as profit when the economy was growing disappears altogether and the business starts making a loss. If losses continue for very long, the shareholders will close the firm down and sell off its assets to recover as much of their capital as they can, no matter how many incomes the firm was still providing to other people.

In an equity partnership, however, everyone with an interest in the company's future gets an agreed share of the firm's income. So if sales go down, investors, workers and suppliers all get less and losses are avoided. But, equally, if sales go well everyone gets more and no profits are made. Everything gets shared either way. This puts everyone on the same side and makes such firms financially very resilient. The technique was used in 2002 by the Hilton = Hotel Group which invested a portfolio of ten hotels in an equity partnership. Another equity partnership then put in £350m to refurbish the hotels.

So at least some of the monetary and financial tools we need to survive in the new world exist or are at least being thought about. But how long will it be before we take the plunge and try them out? Reading this article again, it seems too extreme. I realise that I'm intellectually but not emotionally convinced that we've just moved from one historical phase to another and that a long-term contraction has begun. Consequently, I'm reluctant to take the actions my reason suggests because they go against every precedent and precept I've known.

If many others feel the same, it will be hard for Ireland to make a decisive move in the new direction. A self-help group may be needed so we can give each other confidence and support. If so, the transition initiatives movement4, which is all about making communities better able to cope with the consequences of peak oil, is exactly what we require.

1 Visit http://tinyurl.com/ronanlyons for more information

2 Details on aggressive mutuality can be found on the Feasta website at http://tinyurl.com/mlayden

3 Chris Cook’s 2008 Feasta lecture can be accessed online at http://tinyurl.com/chriscook

4 Visit http://transitiontownsireland.ning.com/ for more information

Related items

-

Green shoots for green building

Green shoots for green building -

Green groups critical of latest budget

Green groups critical of latest budget -

Passive house costs falling, new study finds

Passive house costs falling, new study finds -

Reaching for the first rung

Reaching for the first rung -

Green finance must be longterm & sustainable — Ecology

Green finance must be longterm & sustainable — Ecology -

Why housing isn't viable

Why housing isn't viable -

Irish construction industry has long opposition to higher standards

Irish construction industry has long opposition to higher standards -

Building industry objections to passive house are deeply flawed

Building industry objections to passive house are deeply flawed -

Free training in low energy building starts this month

Free training in low energy building starts this month -

Conference hears of urgent need to upskill Irish construction workers

Conference hears of urgent need to upskill Irish construction workers -

Better Building conference hears commercial property warning

Better Building conference hears commercial property warning -

Glasgow to host conference on passive house at scale

Glasgow to host conference on passive house at scale