- Blogs

- Posted

Building industry objections to passive house are deeply flawed

On Monday the Irish Times reported that both Nama and the Construction Industry Federation (CIF) had objected to plans by Dún Laoghaire Rathdown County Council to make the passive house house standard mandatory for all new buildings under the local authority’s latest development plan, which is due to come into force next year.

The objection of the CIF is not surprising, as the organisation has a long history of opposing improvements in energy efficiency standards. As I have written before, this goes back to the time the organisation objected in the 1970s to the idea of any insulation whatsoever being mandatory in new homes.

The opposition of Nama is more interesting. Tim O’Brien reported in the Irish Times that:

In its submission Nama noted there are currently more than 400 hectares of “serviced and ready” land which could deliver 18,000 housing units, at an average of 43 units per hectare. Nama urged the council to focus on delivery of new homes, saying: “Clearly these lands will have to deliver the heavy lifting in the immediate term, to meet Government requirements on new housing supply”.

The implication appears to be that Dún Laoghaire Rathdown making the passive house standard mandatory would, either through extra cost or the more rigorous design and construction process required, slow down the speed at which new housing can be built. Meanwhile the Construction Industry Federation has erroneously argued that if the passive house standard is introduced, very few new homes will be built in Dun Laghaoire Rathdown in 2016.

All of these arguments are wrong. For a start, the plans won’t come into force until next year, so there’s plenty of time for builders and developers to get to grips with the technical side of the passive house standard, and to ensure tradespeople have the relevant skills. But Ireland already has the highest number of certified passive house tradespeople of any country in the world, and among the highest number of certified passive house designers. So we have the technical expertise.

The speed argument is erroneous too: many timber frame companies, for example, are able to prefabricate passive house systems in a factory and put them up on site quickly, with less exposure of the building structure to the wind and rain.

The argument it will cost more to build to the passive house standard is also wrong. The new issue of Passive House Plus is full of case studies of passive house buildings constructed for fairly normal costs — or in some cases, for even less. At the same time, Wexford developer Michael Bennett & Sons is now planning to offer passive house certified homes in Enniscorthy for just €170,000. And this is without factoring in the money saved over a lifetime of tiny heating bills.

The construction industry has missed the boat when it comes to objecting to higher energy efficiency standards based on cost. The upgrade in energy efficiency standards in the 2008 and 2010 revisions to Part L of the building regulations did increase build costs, the Department of Environment estimated, by about €14,500, for a typical semi-detached home, compared to the 2005 standards. But all the evidence we at Passive House Plus have seen suggests it is no more expensive to build a passive house than to build to the current building regs.

And Nama, which owns land banks in Dún Laoghaire Rathdown, may have a vested interest in opposing the passive house standard. If developers perceive that construction will cost more, they may be willing to bid less for land, driving its value down, meaning Nama will earn less for it.

But perhaps the most disappointing thing is that Nama and the CIF both seem to be arguing for the same quantity-over-quality approach that defined the construction boom of the noughties: throw ‘em up as quickly and cheaply as possible and worry about the consequences later. Which is exactly what occupants of some boom-era properties are now doing.

It’s important to remember that even though Ireland’s building regulations now mandate much higher levels of insulation than during the boom, they are still woefully short in crucial areas like ventilation and airtightness — which are vital for the occupant health and comfort. And more importantly, very little research has been done to see whether our building regulations actually work — that is, whether they really deliver comfortable, warm, healthy buildings with good indoor air quality and low heating bills. The ubiquity of damp, mould and draughts in many of our homes would suggest otherwise.

The passive house standard, by contrast, is backed by mountains of data and was developed by physicists in the 1990s to ensure buildings are extremely energy efficient and that they deliver excellent indoor air quality, prevent condensation and mould, and keep occupants comfortable. But despite all the post-boom talk about upskiling the construction workforce, it seems Nama and the CIF are just eager for us to return to business-as-usual.

Photo by William Murphy and republished under CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Related items

-

Energising Efficiency

-

Big picture - New Zealand rural passive home

Big picture - New Zealand rural passive home -

Podcast: what we've learned from 20 years in green building mags

Podcast: what we've learned from 20 years in green building mags -

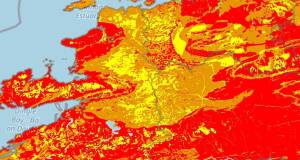

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal

45,000 more Irish homes face radon risk, new maps reveal -

Passive house 30 years on: qualified success or brilliant failure?

Passive house 30 years on: qualified success or brilliant failure? -

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced