- Local Authorities

- Posted

Park life

A new public park on the northside of Dublin combines wind power and sustainable water management with environmentally sound materials and strategies to boost biodiversity, making it a standard-bearer in urban design. Lenny Antonelli visited the site

Construct Ireland readers are used to reading about buildings - their construction details, insulation systems, air-tightness measures, glazing and energy sources. But sustainable design can be applied to other features of the built environment too. Like buildings, parks are a key part of our urban fabric, and their design, development, and maintenance requires more energy and materials than we realise. Shouldn't green building principles be applied to parks too?

The revamped Father Collins Park in Donaghmede on Dublin' northside sets a new standard for urban design. Five wind turbines power electrical functions on site, reed beds filter pondwater, and significant attention has been paid to promoting biodiversity and specifying green materials. The park is a also a key part of Dublin City Council's plan to encourage sustainable transport in the city's North Fringe area, and features two playing pitches, playgrounds, a skateboard park, woodland, picnic areas, exercise stations and an amphitheatre.

The city council announced an international competition to design the new park in 2002. Dublin-based MCO Projects entered, and the firm's design made it to the final shortlist of five, ultimately finishing second to Argentinian architects Abelleyro & Romero. "We were the only Irish architecture company in the final five," says MCO director Eve-Anne Cullinane.

Lining the promenade are five 50kW wind turbines which provide electricity on site

That wasn't to be the end of MCO's involvement though - the firm was asked to manage the project locally by the Buenos Aires-based architects. "We literally hooked up with the winners," Cullinane says. "We ended up forming a company with them and we executed the project while making sure that it was true to their creative design."

Only one other example of wind power in a public park was found by consulting engineers Buro Happold - a 10kW, 40m lattice-tower turbine in Pennsylvania. At Father Collins Park five 50kW Entergrity EW15 turbines - supplied by Perpetual Energy and standing 25m tall to the tower top - line the central promenade, powering lighting features, water aeration, electrical sockets and service buildings. "The idea is that at full capacity they'll power everything on site," says MCO architect Michael Goan. "When the wind's not blowing, electricity is imported from the national grid."

MCO and Dublin City Council will monitor the performance of the turbines closely over the next year. "We'll know how much energy is being generated and how it's performing against targets," Goan says. "Now is only the start of the process of tweaking the turbines to the site conditions."

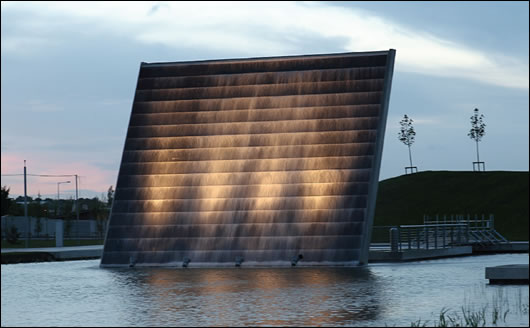

An impressive water feature is situated at one end of the lake

But how suitable is a flat, urban site in the east of the country for wind power? Buro Happold's feasability study found the wind resource to be "fair to good", and estimated the long term average wind speed to be 6.6m/s at a height of 25m. But it also pointed out that commercial wind farm developers typically look for wind speeds of 8.0m/s and over.

Water pumping and aeration represents the biggest electricity demand at Father Collins Park - an estimated 71 per cent (65kw) of the park's total, though this figure was estimated before plans for the reed beds had been finalised. "It's hoped that as the plant life starts to aerate itself that the usage of the aerators can be reduced and they'll come on more intermittently," Goan says.

Lighting is estimated to account for 17 per cent of total demand, while the various buildings should consume about five per cent. Three percent is also allocated for electric vehicles, and one John Deere Gator electric utility vehicle is used for maintenance. Dublin City Council may use Father Collins Park as a charging depot for further electric vehicles in future.

Laneways in the park are well-lit at night

Though Abelleyro and Romero's design envisaged five turbines along the main promenade, other configurations were considered. However, Buro Happold concluded that while fewer large turbines would be more economical, excessively tall structures would overpower the landscape, and have to be sited away from the main thoroughfare. Thus a higher number of smaller turbines - as originally intended - was deemed an ideal solution. The turbines are installed in the water itself rather than on the promenade, and according to Perpetual Energy are the first in Europe to be situated in a lake.

The turbines provide power to four buildings on site - changing rooms, a staff building and two toilets. The changing room facility on the park's western edge was built by a local developer before MCO got involved, but Abelleyro & Romero's design saw it covered with earth to minimise visual impact.

MCO were responsible for the design of three buildings - the staff building and two toilets. The walls of the staff building feature 190mm of Forticrete (a fair-faced concrete block that requires no finishes) internally, a 150mm cavity pump-filled with EcoBead Platinum, and 100mm Forticrete externally, giving a U-value of 0.197 W/m2K. The toilets have a similar construction, with 215mmm standard concrete black internally rather than Forticrete. The staff building is heated by storage heaters, powered by the turbines.

The plan for the park designed by Argentinian architects Abelleyro & Romero

Of course the natural environment is just as important as the built one at Father Collins Park, and detailed ecological assessments of the site were undertaken before work began. Though there were seven hedgerows on the old site - a mix of woodland, sports pitches, and ditches that was also a sore spot for illegal dumping - six of these were removed to develop the park. The oldest and most ecologically important hedgerow, which is dominated by blackthorn and bramble, was retained.

The mature woodland at the park's eastern fringe was in poor health prior to re-development. "The woodland was under threat, particularly because of the sycamore that was in it and a few other non native species," Goan says. "We went through and tagged a load of non-native trees and the initial clear out was done." This clear-out created space for a path through the woodland, now part of the walking and cycling route that encircles the site.

Non native trees were replaced with indigenous varieties such as alder, birch, hazel, hawthorn, holly, blackthorn and oak. Ecological assessments found the woodland likely to provide habitat for bats, wood mice, pygmy shrews, foxes and rabbits, and Goan recalls seeing pheasants and hares on site during development too. Dublin City Council plan to install bat and bird boxes in the park to further encourage wildlife.

FSC-certified timber was specified for park furniture

Over 1200 new trees and 2000 native samplings were planted throughout the wider park, and MCO specified a variety of native species. Trees planted included birch, ash, scott's pine, oak, lime, cedar and horse chesnut; shrubs included dogwood, ivy, rose, honeysuckle and elder.

Philip Crowe elaborates on the planting scheme: "You have blocks of the same tree, and blocks underneath the trees of the same underplanting. So you're going to get a collage effect in autumn and in spring of different colours and textures. One of the exercises we did with the landscape architect [Cunnane Stratton Reynolds] was to take the specification of trees the Argentinian architect had specified and Hibernicise it, if there's such a word, to make it suitable for Ireland."

Pergolas (essentially climbing frames for plants) were seeded with climbers such as Wisteria and honeysuckle. Bulrush was planted along the edge of the lake to clearly mark the point where it ends and the promenade begins (there is no fencing). Reed beds - part of an on-site water recycling system - are planted with a variety of plants including sedges, rushes, sawgrass and bulrush.

The three-level skate park

"It's not the plants themselves, it's the bacteria growing on the roots of the plants which actually take out the nitrogen and all the muck that flows through the water," Goan says. He elaborates on the site's water recycling system: "The drainage for the pitches on one side is collected in a wetland to the side of the lake and once it hits a level it overflows into the lake, and the lake is maintained at a certain level. So when it rains all the water from the pitches is collected and drained away so they don't become waterlogged. When the water in the lake rises, it goes into the reed beds on the far side."

He continues: "Once the water filters through it's collected at a pumping station and, powered by the wind, pumped back up into the lake. There's a series of sensors around all the bodies of water and if through evaporative loss or anything else they start to drop, we actually have a ground water source on site, and a well on site which kicks in and tops it up to make sure everything keeps moving around."

Like water, sustainable materials were another key green theme at Father Collins Park. Concrete with a GGBS content of up to 70 per cent was used on site for the promenade, water features and footpaths. GGBS (Ground granulated blastfurnance slag) is a type of cement derived from steel industry waste - it thus avoids the high embodied energy associated with traditional cement production. Over 240 tonnes of Ecocem's GGBS was used for the project, and the company estimates this will save 220 tonnes of CO2, the equivalent of taking 70 medium-sized cars off the road for a year. "We managed to satisfy ourselves that in putting this much concrete into an urban park that we could do it with the least amount of (environmental) impact possible," Goan says.

Wetland areas will contain and treat park water within a series of reed beds

FSC-certified timber was specified for park furniture, and the ground surfaces - supplied and installed by Go Play - contain up to 92 per cent recycled rubber, derived from older runners and tyres. MCO sourced limestone from Carlow and Kilkenny for the boundary walls. Materials were recycled on site too - soil removed during landscaping was retained to create the hill behind the main lake and to alter the topography as needed.

"We did make a conscious effort, whenever there were decisions to be made (about materials), to make sure it didn't have to travel very far," says Philip Crowe. "It's a matter of getting the balance right between where it comes from, what costs, whether it's the right material, how it's going to be maintained, whether it's durable enough. There's obviously a huge agenda in a park like this in terms of durability, low maintenance, health and safety."

The goal with Father Collins Park isn't just to be sustainable though - it's to provide a working example of sustainability. A website where anyone interested can check wind speeds and real-time turbine performance is in the works, and there are also plans to take schools and other groups on educational tours of the park. Signposts throughout also provide information on the various habitats.

Space was created, through existing woodland, for a walking and cycling path which encircles the park

The park is a key element of Dublin City's council's plan to encourage sustainable transport in the North Fringe - cycling and walking routes through the park form part of a planned 'green route' that will connect nearby residential areas with the Clongriffin DART station, due to open later this year. Cycling and walking routes are also planned along the nearby Mayne river.

"It's all about being able to not use your car," says Crowe. "You might have noticed there's not a car park on site, that was very deliberate. The parking is around the edge of the park and doesn't dominate it. The idea being that people should arrive by foot or by train or on the bus."

During the boom years, it became the norm for sprawling residential areas to be built with little regard for local amenities or public services, encouraging car dependency and the commuter lifestyle. Father Collins Park represents the opposite of that approach - the park was planned while residential development was still taking off in the area. Much of that has now stalled, and empty apartment complexes are a new feature of the surrounding landscape.

But Dublin City Council's foresight to develop a sustainable urban park - and its emphasis on green transport - means the North Fringe won't become the sort of featureless, isolated suburb that remains one of the building boom's principle legacies. "The park is designed to tie together how people are living and working in the area," says Eve Anne Cullinane. "And the key thing is that's there first when all the residential development hasn't come on stream yet. So it's a really good example of where you put the amenity in first."

That's not to say the area isn't populated - on the day Construct Ireland visited the sports pitches were a hive of activity, and there is a large local population in new and old developments. For local residents, the park is now the epicentre of the community. "The idea is that the park is part of the community," Philip Crowe says, "a physical realisation of the community."

Selected project details

Client: Dublin City Council

Architects: Abelleyro & Romero / MCO Projects

Ecological assessments: Faith Wilson/This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Main contractor: Liffey Developments Ltd.

Landscape consultants: Cunnane Stratton Reynolds

Landscape contractor: Peter O’Brien and Sons

Wind power study: Buro Happold

Playground: Go Play

GGBS: Ecocem

Insulation: Ecobead

Wind turbine: Perpetual Energy

- Articles

- local authorities

- Park life

- Father Collins Park

- reed beds

- biodiversity

- MCO Projects

- Abelleyro

- Romero

Related items

-

IGBC launches biodiversity building professionals network

IGBC launches biodiversity building professionals network -

Government announces €45m for social housing retrofit

Government announces €45m for social housing retrofit -

Government, industry and NGOs meet to develop Irish retrofit strategy

Government, industry and NGOs meet to develop Irish retrofit strategy -

Ireland's 1st hemp-built passive house

Ireland's 1st hemp-built passive house -

A low energy, ecological approach to wastewater treatment

A low energy, ecological approach to wastewater treatment -

Encraft host passive house conference for housing professionals

Encraft host passive house conference for housing professionals -

Opinion

-

Thermal bridging

-

Isover awards

-

Carlow A1 upgrade

-

Zero waste

-

Clonakilty eco house