- Renewable Energy

- Posted

Bubble Rap

Although there’s broad agreement that the escalation in house prices in recent years has gone too far, the very real possibility of an over correction fueled by a panic mentality could have disastrous implications for homeowners, banks and the entire economy. Richard Douthwaite proposes measures including energy upgrade of the housing stock which, if urgently implemented, could help to avoid economic meltdown, and Jay Stuart outlines some energy saving measures which could be rolled out

After the election, while the Greens were negotiating with Fianna Fáil to see if a coalition could be worked out, many people remarked that if the property market collapsed, their time in government would turn out to be a poisoned chalice. So, now that the Greens hold some of the levers of power, what are the prospects that property prices will slump catastrophically during their term of office? And are there any particularly green levers they can pull either to prevent that happening or to ameliorate the situation if it does?

The problem in the property market is that a bubble has developed, inflated with borrowed money. As every reader of Construct Ireland knows, thousands of people have borrowed on the basis of the market value of their property to buy more property. This has pushed property prices up, which in turn has enabled more, and larger, loans to be taken out to finance further property purchases. The cycle has gone round and round with prices getting higher and higher at each turn.

The inevitable result has been to push house prices out of line with reality – or in other words, with wage levels, as Illustration 1 shows. The cost of servicing the average new 25-year mortgage is significantly above the thirty-year average of 28% of average earnings. At the end of last year it stood at 33.8% and the Bank of Ireland expects it to rise further still. The most recent (March 2007) issue of the bank's Irish Property Review says that “affordability is likely to deteriorate further in 2007 and 2008, reflecting the full impact of rising mortgage rates.” It expects the cost of servicing a new mortgage to rise to 38.1% of income in 2007 and then 39.4% in 2008. “This level of servicing was last seen in the early and mid-1980’s, when interest rates were over 15%, and can be expected to have an impact on the market” it comments dryly, without suggesting what that impact might be. (see illustration 1)

Illustration 1: Since 1995, Irish house prices have more than tripled in relation to other prices and in relation to people's incomes. They have also roughly doubled in relation to rents. They are consequently far ahead of their long-run levels. Index: 1995 Equals 100 Source: Morgan Kelly, Quarterly Economic Commentary, Summer 2007, ESRI

On these figures, house prices would need to fall by roughly 25% to return affordability to their long-run level. However, a bigger fall is suggested by two other indicators. One is the fact that, over several decades and in many countries, the median house has cost roughly three times the median gross income. Demographia, an organization which tracks house prices using this measure, rates Dublin house prices as 'severely unaffordable' in its January 2007 report. “The present extent of housing unaffordability is unprecedented, both historically and across markets” it writes. “Most housing markets have exhibited median multiples of near 3.0 or less in the past and many still do.” The Dublin figure is 5.7 which indicates that house prices could fall by almost half.

The other indicator is the ratio between mortgage lending and personal disposable income. The value of the mortgages outstanding at the end of April, e128,722 million, was 1.4 times the total of every private Irish resident's after-tax income during the year. This was twice the borrowing-to-income ratio seen as recently as 1999. The rise shows how much extra debt we took on in a very short period and consequently now have to service at a time when interest rates are going up.

A study 'On the Likely Extent of Falls in Irish House Prices' by Dr. Morgan Kelly of UCD published by the ESRI in July this year suggests that “falls of real house prices of 40 to 60 per cent over a period of 8 to 9 years” are likely. However, Kelly says that the decline could be much more rapid and that Ireland could experience a crash similar to that in Arizona. “Until late 2005, Arizona was experiencing a house price and construction boom similar to Ireland’s” he writes. “Then, as sales of new houses stalled around the start of 2006, building fell suddenly: from around 8,000 starts in May 2006 (similar to Irish levels last year) to around 3,000 in November.“

Staff at the Central Bank became concerned about the possibility of banks being written off earlier this year when they carried out a correlation analysis and found that, if house prices fell, other property prices were likely to fall by much the same amount

Housing starts are already falling steeply in Ireland. Builders registered plans to build only 3,000 new houses in June this year, a 60% drop on the record 7,900 recorded in June 2006. Developers are closing sites because they are not prepared to face a loss on every house they sell. "Registrations are down by a third in the first half of the year compared with 2006. It looks like builders are adjusting to the property downturn faster than anyone expected," John Beggs, chief economist at AIB Global Treasury, commented.

House prices are also falling. According to the Permanent TSB index, they fell nationally in March, April and May by a total of 2.2%, so that at the beginning of June they were only 2.6% above their level in June the previous year.

Ireland is much more likely to experience a disastrous housing price crash than other countries because of the importance of the buy-to-let investor. In December 2006, for example, 24.6% of all residential mortgages were taken out by people buying to let. a proportion that had increased steadily over the previous three years, in part because of the increased availability of interest-only mortgages. Most of those who took out these mortgages were using the security of properties they already had to buy more property. Most, too, were more interested in the prospect of capital appreciation as house prices rose than in any rental income they might receive since they were using their rents to service their loans. In other words, they were indulging in pure speculation aided and abetted by the banking system.

So what will these speculators do now that the market has turned and they realise that they stand to make capital losses for several years rather than capital gains? The fear is that many will try to sell their properties before prices drop any further, and that this will precipitate a house-price crash. In the Central Bank's Quarterly Bulletin for April this year John Kelly and Aisling Menton write:

More recently, [buy-to-let] investors have again been cited for fuelling house-price increases in 2006 and making it difficult for first-time buyers to get onto the property ladder. The possibility that investors may present risks to the stability of the Irish housing market has also been widely discussed. In its first Financial Stability Report (Central Bank, 2002), the Bank expressed the view that new investors might ‘‘be particularly vulnerable to any fall in property and/or rental values’’. The IMF and the OECD have also expressed concerns that the rental market is dominated by small — individuals who own one to three properties — and ‘‘mostly inexperienced investors’’ (Rae and van den Noord, 2006), who might attempt to sell if interest rates rose and/or house price increases stalled.

One thing that may slow the rush to the exit is that rents are going up because, now prices are falling, many potential house buyers are delaying purchasing and, instead of moving into their own houses, are staying longer in their rented accommodation. This has increased rental demand. However, the reluctance to buy means that properties are taking a lot longer to sell which in turn tends to accelerate the rate at which prices fall.

Public transport system developments should be pushed ahead – the various Luas lines and the Dublin to Navan and the Sligo to Galway rail lines are obvious candidates

Property prices certainly need to fall so that they can recover their long-run relationship with people's earnings and it is far better that they do so quickly than over a period of years. A slow descent becomes impossible once the banks accept Morgan Kelly's view that house prices are likely to drop by, say, 50%, since they can no longer accept the collateral value of a property as being its price today. Instead of offering 100% mortgages, they should only offer 50% ones. This would make it impossible for most people to buy, even if they were prepared to accept the risk of a big capital loss themselves. So, once the conventional wisdom is that prices will fall, they will fall, and fall rapidly.

However, a rapid house price fall presents two problems. One is that such falls tend to go too far, overshooting the eventual stable price level. The other problem is that a big drop in property values could put the banking sector at risk. This is because property-related lending (in other words residential mortgages and advances to the real estate and construction sectors) was almost 60 per cent of the banking sector’s outstanding loan book at the end of 2005. If just 10% of the amount outstanding had to be written off, the banks could be written off themselves. The Central Bank became concerned about this possibility earlier this year when two of its staff carried out a correlation analysis and found that, if house prices fell, other property prices were likely to fall by much the same amount.

The overshoot is just as much of a threat to the banks as the 'required' fall itself. Banks could do much to limit it by building a collective lifeboat, a House Price Support Vehicle, to step into the market and buy up every decent, well-located apartment or three-bed semi offered once the price drop has passed a certain point. Houses bought by the lifeboat would be trickled back on to the market once prices had stabilised and any losses would be shared amongst the banks in proportion to the amount of mortgage lending each is currently doing. The government should help their effort by buying houses on behalf of local authorities to be used for social housing. This would improve the social mix on many estates and, as the 2006 Census showed that this country has almost 300,000 empty dwellings in addition to 1,500,000 houses in daily use, building additional units for social housing in many areas would not make sense.

In this way, the responsibility for limiting the damage caused by the deflation of the bubble would be shared by those responsible for blowing it up. The banks must take most of the blame since they progressively made it easier for people to borrow larger and larger sums. As recently as 2002, they limited house buyers to borrowing 2.5 times the primary income plus once times the secondary one. Now, five times the joint income is common. Similarly, 100% mortgages for first-time buyers were recently introduced and mortgage periods have been lengthened from the traditional 25 years to 35 or 40.

However, the government is also to blame because it either stopped the Central Bank from preventing the banks lending so lavishly or failed to insist that it did so. The Central Bank should have:

Banned lending to buy-to-let customers based on the security of other properties rather than the rental income from the property concerned.

Banned interest-only loans

Restricted the number of multiples of the borrowers' incomes that could be given as a mortgage

Limited the amount that could be borrowed on a property to, say, 90% of its value.

Consequently, if it does turn out that, despite preventing the overshoot, the banks' solvency is threatened by the price collapse and its consequences, the government will have to do what it did in 1984 when it saved AIB after its ill-judged purchase of the Insurance Corporation of Ireland was found to have made it liable for massive underwriting losses. AIB said that these put its core banking business in jeopardy so the State bailed it out at a cost of £400 million, the equivalent of about e900 million today. There's no way of estimating how much it might cost to rescue the banking system this time, but if called upon to do so, the State should make sure that it does what it failed to do with AIB and gets shares for the National Pensions Reserve Fund for the money it puts in.

However, much the best way for the government to limit a price collapse is to stop the problems in the housing market from spreading to the rest of the economy. This involves two things: ensuring that the money supply does not contract because people take out too few new loans and getting house-building workers re-deployed to other types of construction. As illustration 2 shows, the rate at which mortgages are being taken out is falling steeply and, if the present rate of decline is maintained, repayments may exceed new mortgage borrowing within a year. This would be disastrous for the economy as, unless other categories of borrowing increase by enough to compensate, the amount of money in circulation will begin to shrink and make it increasingly difficult for anyone to do business. I know how hard this is. When I ran a business in the early 1980s, I had to spend hours on the phone chasing my customers for payment and the only way I could be sure of getting it was to refuse them further supplies, even though they needed them, until their accounts were up to date. Meanwhile, my suppliers were chasing me for money and I could not order again from them until I'd paid. The whole economy had sludged up.

Illustration 2: The rate at which people are taking out mortgages is dropping steeply. Source: Central Bank of Ireland.

The government must therefore ensure that enough is borrowed every month to guarantee that, at the very least, the money supply does not fall. Indeed, ideally, the supply should rise a little every year as this would enable the economy to continue to grow. If the State cannot create a climate which encourages businesses and the public to borrow enough to stop the supply shrinking, it must make up the shortfall itself. However, its strategy should be that, whenever possible, it avoids borrowing for its own projects and uses its borrowing capacity to leverage much larger borrowings by the private sector and the general public.

The greatly reduced rate of housing starts has already led to a jump in the number of building workers signing on. The number of people on the Live Register increased by 12,353 to166,363 during June, and most of the additions were men. The government therefore has no time to lose in coming up with plans to keep most builders occupied. This is going to be difficult as building trade employment expanded from 100,800 people in 1996 to 263,000 in 2006 and Ireland is spending three times as much on building houses as the average European country.

Even so, it is crucial to stop unemployment worsening. Increased joblessness would not only be distressing to the people involved, politically damaging and a waste of resources but it would also undermine the efforts to limit the damage to the banking system. This is because unemployed people would not be able to maintain their mortgage repayments and those of them with debts greater than their property's value would be tempted to call at their bank's offices and hand over their house keys to get out their situation. If it accepted the keys, a bank would have to register a bad debt on its books. This would erode its working capital and thus destroy its ability to lend so much, which in turn would harm the attempt to keep borrowing levels high.

If house building almost stops, as seems likely, what other construction activities could the workforce take on? And how might the government persuade people to borrow almost as much as they have been borrowing recently for mortgages for these new types of development? This is where the Greens come in. The Greens are more aware than any other party of the coming energy crunch and the need for Ireland to invest to reduce its fossil energy use. Ireland should therefore use the workers becoming available to make a dash for energy self-sufficiency while the other factor required to make the switch, fossil energy, is very cheap in relation to the prices that can be expected in future.

The possibility of accelerating the rate at which windfarms are added to the grid should also be investigated

The first step should be taken immediately, before people get so depressed about the state of the economy that they become reluctant to do anything, let alone take on more debt. Within the next few weeks Sustainable Energy Ireland should announce a scheme to grant-aid householders to improve their energy efficiency. e100m. funding for such a scheme has already been announced in the Programme for Government. What I have in mind is that a surveyor would use heat imaging equipment to take actual base-line measurements of a house's energy efficiency before any work was done and then again when it had been completed. The grant paid would be proportional to the energy savings achieved so that the biggest grants were given to those who had been living in the least-energy efficient houses.

The cost of the work over and above the amount covered by the grant would be added to the householders' mortgage whenever that was requested. This would not only help maintain the lending level but would increase the collateral value of the house and make the householder a better credit risk as his or her energy outgoings would be reduced. Ideally, whole estates of similar houses would be improved simultaneously to keep the costs to the owners down. Specialist contractors would probably emerge who would charge for their work according to the improvement in the energy efficiency they delivered.

The Greens should resist any calls for road projects to be brought forward to provide construction-sector employment because, as they know, we won't have the fuel to maintain current levels of road use. Instead, public transport system developments should be pushed ahead – the various Luas lines and the Dublin to Navan and the Sligo to Galway rail lines are obvious candidates. They should also commission research on the re-development of Ireland's inland waterways. Such a study might discover that pumping water from the West to Dublin through a pipe made less sense than building a new canal as the latter would provide recreational opportunities and a low-energy way of moving bulk freight as well.

The possibility of accelerating the rate at which windfarms are added to the grid should also be investigated since there is a long backlog of applications from firms wanting grid connections and unable to get loans to erect their turbines until they do. And if, in addition to the onshore windfarms, incentives were given for the development of offshore ones along the west coast, how effective would that be in terms of employment creation and boosting the money supply ?

Extensive windfarm work would necessitate strengthening the power grid and building one or both of the proposed interconnectors with Britain. It would also require the installation of smart meters in people's homes. These meters decide when to turn on and turn off appliances according to the price of power. They would, for example, turn on the immersion heater in the bathroom or give the freezer a blast whenever wind energy was available at a good price. The installation of collective biomass-fired district heating systems should also be assessed for their carbon-reduction and energy-saving potential.

In Scotland it is estimated that for every e70,000 spent on insulation work, a job is created somewhere in the economy for a year. A great deal of work could therefore be created on energy-saving and renewable energy projects provided people's confidence, and thus their willingness to borrow, can be maintained. This is going to be hard to do and the government may have to undertake a lot of borrowing itself until confidence returns. The abyss before the government may become so dark and deep that it has to consider using other measures, such as the introduction of a land tax as well. I'll discuss what these other measures might be next time.

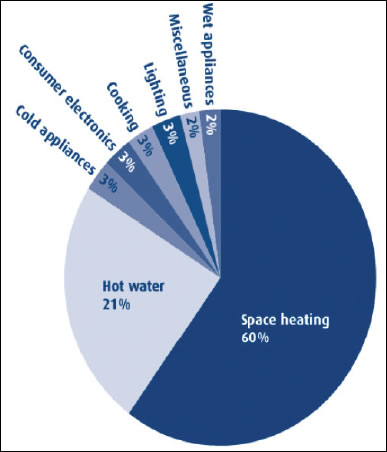

Illustration 3 : How a typical household uses its energy. The biggest potential savings are in space heating and hot water provision, making these the obvious target for a grant system.

Energy renovation options

Jay Stuart of Delap and Waller EcoCo integrated sustainable design consultants completed a renovation of a 1970s house last year which addressed most of the issues of energy efficiency with a comprehensive approach. Here he outlines his assessment of the issues that should be addressed by the government.

The renovation of the existing housing stock is a great opportunity which could yield great benefits for the economy, the building industry, home owners and the carbon emissions of the nation. An investment in this area would reduce the carbon emissions and therefore the Kyoto fines we are all faced with in the period 2008 to 2012. We will start accumulating these fines in 6 months so there is no time to lose. With carbon fines projected to average e30 per tonne in the first Kyoto period and with most houses generating about 8 to 10 tonnes of CO2 per year any investment in the energy efficiency of the housing stock could be partially paid for by the avoidance of these fines.

A 50% reduction in emissions per house would generate a e120 to e150 saving per annum in Kyoto fines. Amortised over 25 years this money could be the basis for financing the grant scheme to encourage investments in energy efficiency in the existing housing stock. As the Building Energy Ratings scheme starts to influence house values in the market there is support in the market for banks and mortgage companies to offer “green loans” for individuals to invest in energy efficiency. The green loans could be repaid with the savings on energy bills which could be about e750 per annum for an average house. A combination of a grant scheme and green loans should be sufficient to kickstart such a programme of investment.

All this happens to coincide with a downturn in the new housing sector of the building industry so shifting the resources and employment of the industry to the existing housing stock would maintain the significant contribution the building industry currently makes to the economy and to the government’s tax revenue on top of the social benefits of productive employment of thousands of people.

There has already been good research completed in this area and there is no need to commission another study. Now is the time to implement action. Homes for the 21st Century, the 1999 study by the Energy Research Group at UCD details the many benefits in the public domain as well as those for the resident. There is a good study of housing in Ballyfermot completed by the charity Energy Action and Alembic Research which calculates the costs of upgrading houses in the area and the CO2 savings that would result. These studies show that a major reduction in energy use and carbon emissions is very achievable with cost effective measures, and that is my experience in practice.

CFL bulbs can reduce energy use for lighting by 80% and their life cycle shows them to be a better investment by far

The housing stock varies enormously in terms of its age, construction and energy performance and so the measures to improve their performance will vary in detail. However there are common measures which would apply to all housing and a number of ‘packages of measures’ could be offered depending on the owner’s choice and the grant made available.

I would propose a series of packages similar to these:

Package 1 – the “low hanging fruit”

Install an electricity monitor to display real time patterns and records of electricity use. Research shows the feedback information provided enables the consumer to adjust their behaviour to reduce electricity consumption on average by 15%, at a cost of circa e115.00.

Install low energy light bulbs. Energy efficient CFL bulbs will soon be closer in cost to incandescent bulbs due to the announced tax on incandescents. CFL technology will reduce energy use for lighting by 80% and their life cycle shows them to be a better investment by far. A study of the cost of doing this compared to the cost of building a power station to provide the energy for incandescent domestic lighting would provide, I suspect, a strong case for implementing this as a better investment, at a cost of circa e150 per house.

Install a chimney damper. About 10% of your heat goes up the chimney. An openable chimney damper can be installed externally very simply, at a cost of circa e300 to buy.

Draught-proof the window and door openings. Depending on condition this can be done for e200 material costs.

Insulate the attic to a depth of 400 mm with mineral wool. This is easy to do in most attics where the insulation, if there is any, is laid on the ceiling. You only want to do this once so exceed the minimum standards and anticipate energy costs for the next 30 years. Costs from e1,500 for materials only

Package 1 total cost: e2,265 plus labour

Savings potential: 30% heating energy & 30% electricity plus 2 tonnes CO2 per year

Package 2 – heating system upgrade

Install a new high efficiency condensing combination boiler with flue heat recovery device and recycle redundant copper hot water cylinder. Together with this provide a good heating control system with thermostatic radiator valves and zoned control.

Package 2 total cost: from e5,000 installed

Savings potential: 30% of heating and DHW energy and costs, plus 2 tonnes CO2 per year

Package 3 - major 30 year renovation (including Package 2 )

Insulate the walls: either inject the cavity walls with full fill insulation if a cavity is available or add insulated plasterboard internally or insulate externally.

Insulate the floor: insulate joisted floor to depth of joists and make airtight or add insulated chipboard subflooring to ground floor if concrete.

Make the house airtight: use proprietary airtight tapes to seal all window and door frames to adjacent plaster finish. Cover tapes with insulated plasterboard into reveals. Spray specialist insulation in zones where floor joists meet external walls to make this difficult area airtight and insulated.

Install designed ventilation system with heat recovery. This can be a mechanical heat recovery ventilation system or a passive system such as Dwell-Vent.

Package 3 total cost: dependent on specific house

Savings potential: from 20% to 40% of space heating energy, plus 2 tonnes CO2 per annum

By installing a mechanical ventilation system with heat recovery into an airtightened house, substantial energy reductions could be achieved

- Articles

- Opinion

- Bubble Rap

- property

- crash

- economic meltdown

- energy saving

- mortgage rates

- house prices

- recession

Related items

-

AIB launches new ‘green mortgage’ for low energy homes

AIB launches new ‘green mortgage’ for low energy homes -

New Leeds developer goes passive

New Leeds developer goes passive -

Bank of Ireland unveils new green loans

Bank of Ireland unveils new green loans -

Housing ‘race to the bottom’ bad for climate & quality — energy expert

Housing ‘race to the bottom’ bad for climate & quality — energy expert -

Reaching for the first rung

Reaching for the first rung -

New Europe-wide boost for energy efficient mortgages

New Europe-wide boost for energy efficient mortgages -

New property finance platform offers chance to invest in Dublin passive house

New property finance platform offers chance to invest in Dublin passive house -

Why housing isn't viable

Why housing isn't viable -

Passive house or equivalent - The meaning behind a ground-breaking policy

Passive house or equivalent - The meaning behind a ground-breaking policy -

District heating and passive house - are they compatible?

District heating and passive house - are they compatible? -

How to stimulate deep retrofit

How to stimulate deep retrofit -

Delivering passive house at scale

Delivering passive house at scale