- Renewable Energy

- Posted

For peat's sake

Up till now, the activities of semi-state energy companies like Bord na Móna, ESB & Bord Gais have not won the favour of environmentalists. Richard Douthwaite explains how that situation is destined to rapidly change, and exclusively reveals details of the ambitious new green direction being adopted by Bord na Móna

In early December, Gabriel D'Arcy, Bord na Móna's recently-appointed CEO, gave a PowerPoint presentation to minister for the environment, John Gormley, setting out the company's plans for the next ten years. What he said was astonishing and, if his plans materialise to turn it into not just Ireland's leading renewable energy supplier but also its leading recycling company, the semi-state will be transformed out of all recognition. Certainly, harvesting and selling peat, which currently provide half of its income, will play a much-diminished role.

But BnaM is not the only state company trying to change radically. The ESB says it plans to become “a world class renewables company” and its executive director for sustainability speaks of a massive cultural change in the organisation. Similarly, Bord Gáis says that “renewable energies are very much at the forefront of our business strategy” and that it has set up a e10 million research fund for them.

For its part, Coillte says it is looking at wood energy in great detail, evaluating where the opportunities are. “We're trying to take a lead. We'll have more to say about that in a couple of months,” a spokesman said. It also thinks that it has the opportunity to be “one of the biggest players” in wind energy particularly as, since it owns 7 per cent of the country, it has a lot of suitable sites.

Bord na Móna's strategy is based on two things. One is that peat is Ireland's most damaging fuel in terms of its carbon emissions per unit of heat delivered. The other is that it cannot continue to exploit the raised bogs in the Midlands at the current rate.

The company says that this is not because the resource is worked out but because it is no longer justifiable to open new bogs because bogs act as carbon sinks and the burning of peat contributes to CO2 emissions. “We could go on doing what we're doing at the rate we're doing for the next twenty years,” a spokesman says. “It's just that it's no longer a sustainable option”.

Even bogs which Bord na Mona has already opened may not be available to it. “The company drained a 100 hectare bog near Abbeyleix about 25 years ago but when it wanted to dig it in 2000, there were local objections and it backed off because of the bad publicity it was getting. That bog is now being restored,” says Dr Catherine O'Connell of the Irish Peatland Conservation Council.

“Only a tenth of Ireland's original 308,000 hectares of raised bogs are left with some conservation value and of those, only 1,945 hectares are good enough condition to still be developing and sequestering carbon,” O'Connell says. “Most of what's left is either a Special Area of Conservation or a Natural Heritage Area, or in the process of becoming one.”

There's not a lot of bog is left in the West, either. In Mayo, for example, 71 per cent of the blanket bog has gone. Moreover, BnaM's production of milled peat was never particularly successful there as the higher rainfall made it hard to get the product dry.

So when D'Arcy told the minister that the company would not open any new bogs, a pledge he first made last July, he was being realistic. There would be little political or physical scope for the company to do so. BnaM knows it has to take a very different direction if it is to survive and sees innovation as the key to that direction.

The first step in its survival strategy is to do the things that it is already doing but to use less peat. For example, it is already replacing part of the peat that it has been burning at its Edenderry power station with meat and bone meal, chopped miscanthus (also known as elephant grass) and woodchip from forest-thinnings and “short-rotation coppice” - specially-grown willow and poplar trees that are harvested regularly and spring again from their roots.

Experiments in biofuel: algae being grown vertically by US company Valcent

While Bord na Móna already co-owns Ireland’s first wind farm in Bellacorick, County Mayo (above), it is also planning to build one of the largest on-shore wind farms in Europe in the same region, near the site of the now-demolished power station (see bottom of page) which it once supplied with turf

This is not a particularly good use of the biomass as a high proportion of the energy from its combustion is lost because the station – like all conventional, centralised power stations – is only about 38 per cent efficient. However, Dr Hubert Henry, BnaM's director of innovation and R&D, hopes to minimise the loss by using some of the waste heat to warm greenhouses.

However, he's also considering a much more exciting use for the heat, one which gives hope that the Edenderry plant will be able to stay open after 2015 when its planning permission runs out. Henry points out that the company owns a lot of cut-over bogs near the power station which could be flooded. The waste heat could warm the resulting lagoons and they could then be used to grow algae which could be dried and burned as a fuel. Carbon dioxide from the station's chimney could fertilise its growth.

“We could use the algae for three things,” he says. “It could be a biomass feed for the power station. We could extract the oil the algae contains. This would be a third-generation biofuel. And we could compost it for use in our horticultural compost products.”

These are not just wild ideas. Henry's innovation department has a budget of e5

million a year and employs thirty highly-qualified people. It also draws on the resources of most Irish universities. “We're innovation driven. It plays a central role in what we do,” he says. “We've also got an innovation satellite unit in each of our operating units. Those involve another thirty people.”

A great deal of work is going on around the world breeding algal strains for energy production but most of the breeders' emphasis has been on increasing their oil content. So far, however, the oiliest types have had to be grown in a closed environment to prevent them being out-competed by more vigorous wild ones. As a result, they would be unsuited for BnaM's open ponds but that does not matter because it is the total weight gained rather than the oil content that is important if algae are to be used as power station fuel and compost as well.

Other ways the company is exploring to use less peat include incorporating saw dust in its domestic briquettes. These may eventually be made entirely from compressed wood and it recently put a range of compressed wood logs and wood pellets on the market. Similarly, the company's horticultural division is trying to reduce the peat content of its composts to just 10 per cent by using composted green waste from its composting plant in County Kildare.

It is also looking for higher value products from the peat it will produce. The company is working with the Carbolea group at the University of Limerick to see if pyrolysis and hydrolysis can convert peat into “platform” chemicals which can then be made into plastics and other valuable products. At present, however, BnaM's emphasis is on turning the chemicals into liquid fuels.

Since BnaM purchased Advanced Environmental Solutions, the company has been processing about 275,000 tonnes of waste a year from 55,000 homes and 6,000 commercial premises through depots in Navan, Nenagh, Tullamore, Portlaoise and Wexford. Its aim is to become “Ireland's leading resource recovery business” with over 80 per cent of its throughput being recycled. It achieves about 50 per cent at present. Some of the raw material for its compost and wood fuels is already coming from these activities. Its composting plant in Kilberry, County Kildare currently treats 44,000 tonnes of green waste and its target is to be composting 150,000 tonnes by 2013.

The new BnaM likes superlatives. It is planning to build “one of the largest onshore wind-farms in Europe”, with over 400MW capacity, near Belacorrick in County Mayo, not far from Ireland's first windfarm which it now part-owns. At the time the latter was built, the company was harvesting peat for a nearby power station, which has since closed. As a result of winning the contract to handle the windfarm's maintenance, it, and Eddie O'Connor, its CEO at the time, became aware of windpower's potential. O'Connor, of course, left to set up Airtricity and now BnaM is following in his wake. As its wind energy supply will be intermittent, it also plans to install 500MW of generators in Offaly and Westmeath – some using gas, others running on oil, so that it can supply the national grid at peak times.

There are two particularly ambitious goals in BnaM's plans. One is its target of linking an amazing 250,000 houses to district heating systems within the next 5-7 years. The heat will come from combined heat and power plants using sustainable fuels. The company describes the project as a “e500m opportunity” and Henry insists that the conversion will involve insulating the houses where necessary. “There's no sense in pouring in heat only to have it pour out through the walls and roof.” It is piloting this as part of Sustainable Energy Ireland's Dundalk 2020 project, supplying heat to Dundalk Institute of Technology, the hospital and some near-by housing estates.

An aerial view of a bog harvested by Bord na Móna in the Bog of Allen, County Kildare

One of the sustainable fuels used by the CHP plants may be gas. Some of the organic waste the company collects could be turned into synthetic natural gas either for its district heating systems or to be fed into the national gas grid as is done already elsewhere in Europe. A recent report from the National Grid company in Britain claims that up to half Britain's domestic gas heating could be met by turning waste into gas. Two processes would be used – anaerobic digestion for wet waste such as sewage and animal manure, and pyrolysis for drier wastes such as wood and energy crops.

The other ambitious – and somewhat more controversial – project BnaM is considering is joining with others to pump water from the Shannon catchment to Dublin. “We've got potential sources and a lot of the land through which the pipeline would have to run. We'd put a treatment plant on one of our properties,” Henry says.

The company owns 200,000 acres of peatland and is planning to spend e10m on rehabilitating everything for which it no longer has a use. “We want to reduce the carbon footprint of the company. We want to turn the land from being a carbon source back to being a sink,” Henry says. “We've got a full-time ecologist, Dr Catherine Farrell, working on our restoration projects.”

He mentions Oweninny bog in Mayo where the company has carried out what it says was the largest rehabilitation programme ever attempted in Europe. This involved blocking field drains so that the 6,500 hectares site became wet again and the surface was “sculpted” by machines. The final operations were carried out in 2007 and it was left to Nature to restore the peatland plants. “They are coming back remarkably quickly,” he says.

BnaM plans to spend e1.4 billion in total over the next five years. The ESB intends to spend at least that each year. Its board approved a 14-year e22bn investment programme, Strategic Framework to 2020, in March 2008, which, amongst other things, is to set the company on a course to cut its Irish emissions by 30 per cent by 2012, 50 per cent by 2020 and to be “net zero” by 2035. (“Net zero” means that the emissions from one company activity will be offset by it somewhere else.)

Although not all of the e22bn will be spent in Ireland, e4bn is to be invested in renewable energy projects here and e6.5bn spent on enabling more intermittent renewable energy sources to be connected to the grid. This will be achieved by installing a smart meter for every customer and by changing the way the distribution network is configured so that it can accept power supplies from micro-generators and other smallish sources such as CHP plants dotted around the country.

“The old, top-down, one-way flow of power from big stations to the periphery no longer suits the emerging technologies,” says John Campion, its sustainability director. “We're building a smart network that can handle not just a two-way flow but also supplies and loads that cut in and out. This involves remote control switching and a lot of automation.”

Changes to the transmission grid are also necessary because there will be 6000MW of wind capacity on the network by 2020 and it has to be able to cope. “Although Eirgrid operates the grid, the ESB owns it, pays for it and does the work on it,” Campion says. “We've been investing e1 billion a year recently so the overall programme involves a 50 per cent increase. I'm sure that can be achieved.”

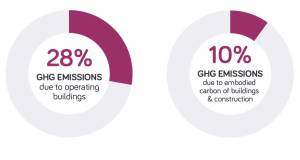

At present, the ESB emits 15 million tonnes of carbon dioxide a year, two thirds of all the emissions from the electricity sector and just over 20 per cent of the country's total. A 30 per cent reduction in this by 2012 would therefore be a significant achievement. The plan is to bring about it by switching from oil to gas and also by using more wind power.

“We are not allowed to generate more than 40 per cent of the country's power for competition reasons. This means that, if we bring more wind on line, we have to cut our conventional production. So what we've done is to sell two of our oil-burning stations and we're replacing that capacity with new 400MW gas-fired station at Aghada, County Cork and wind. The people who bought our oil stations will switch them to gas but we couldn't have done that ourselves,” Campion comments.

Despite claims to the contrary in the Dail, Campion says that the smart meter project is on schedule and that the first 800 meters were installed by the end of December. “Nobody has done anything like this in the world,” he says. “People talk about the Italians installing smart meters but theirs aren't smart at all. Ours will be absolutely leading edge.”

Two trials are being carried out so that specifications can be established. One is an investigation into the way the meters affect consumer behaviour. “We'll have 6,500 meters installed by the end of April. Of these, 1,200 will have in-home display units so we can see what difference it makes if people are given information about the cost of their power.”

Fiddandary mountain blanket bog, County Sligo

Turlough Hill, the ESB’s only pumped storage hydro-electric station, situated in County Wicklow

The other pilot is designed to test various ways that the meters could be controlled remotely by the electricity supplier and communicate information back. An additional 10,000 meters will be installed before the end of the year using “General Packet Radio Service” - GPRS - a mobile phone technology, and a Programmable Logic Controller (a “PLC”) to switch things on and off. “As we'll be putting in 2 million meters in all,” Campion says, “we need to get it right.”

The meters are seen as essential if a lot more use is to be made of windpower, as they will allow people to carry out electricity-intensive tasks, like charging the battery of an electric car, when the wind is blowing and power is cheap. In fact, Campion thinks that the government target of having 10 per cent of vehicles being powered electrically by 2020 is too low and he'd like to see it doubled. The ESB already operates six electric vehicles and is working with fleet owners like An Post to encourage them to buy some too.

When asked about electricity storage, Campion says that the ESB has no plans for more pumped storage on the lines of Turlough Hill. “It would be difficult to get the transmission lines built. There'd be too many objections,” he says, adding that that the company is interested in using the batteries in customers' private vehicles for storage. We would top up our batteries at a low price and be paid a premium if power was taken out.

Campion thinks that the final phase of the ESB's emissions reduction plan – cutting them from 50 per cent of their present level to zero by 2035 will be toughest of all. “We'll still be burning fossil fuels,” he says, “so the plan is to rely on carbon capture and storage which should be a fully developed technology when we have to replace Moneypoint sometime between 2025 and 2030.”

The ESB does not feel the need to develop its own technologies since, unlike Bord na Mona with peat, there is a lot of electricity research going on around the world. Instead it relies on ESB International to keep it up to date. “We've got over 1,000 people working in over 30 countries around the world. They know what's going on.” However, it does believe in backing new technologies when it finds them and, in January this year, set up a subsidiary, Novus Modus Ltd., with a budget of e200 million over five years to bring new products to market.

By contrast, Bord Gáis is planning to fund research and development in alternative energy. It announced last year that it would spend e10 million on developing “biogas, gas as a transport fuel, marine renewables and fuel cell technology.” It is also spending e50m on a windfarm in the west of Ireland which will open in 2011. However, its main thrust at the moment seems to be to compete in the electricity market and has a e400m combined cycle gas fired power plant currently under construction at Whitegate in County Cork.

Commenting on the company’s move into the residential electricity market, a Bord Gais spokeswoman told Construct Ireland that “to offer competitive, dual-fuel, sustainable offerings to current and new customers we plan to develop and build a diverse portfolio of assets within the Irish energy sector, both conventional and renewable.”

I find it encouraging that two big state companies are responding so positively to the urgent need to move to a low carbon economy and that all four semi-states I approached for this article are moving in that direction, albeit at different speeds and in different ways. I see that diversity as a strength. It would be worrying to find them all perfectly in step carrying out the same co-ordinated centrally-dictated plan.

My only worry is that the ambitious plans drawn up by Bord na Mona and the ESB might soon be seen as the product of the go-ahead Celtic Tiger era and out of keeping with a period in which we need to cut back and be more cautious. Quite the opposite is true. Those parts of their plans which cut both emissions and imports are exactly what the country needs. They have to be carried out.

- Articles

- renewable energy

- For peat's sake

- douthwaite

- Feasta

- Peat

- fossil fuels

- bord na mona

- bord gais

- esb

- district heating

Related items

-

Grant invests in biofuel tech for oil boilers

Grant invests in biofuel tech for oil boilers -

Oil heating sector pivots to biofuels, but green groups raise concern

Oil heating sector pivots to biofuels, but green groups raise concern -

Architects call for urgent climate action ahead of COP 26

Architects call for urgent climate action ahead of COP 26 -

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries -

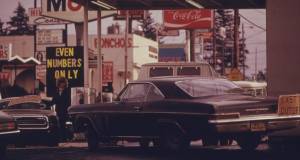

The first oil crisis

The first oil crisis -

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March

SEAI Energy Show back at RDS on 27 & 28 March -

New research finds air pollution particles in human placentas

New research finds air pollution particles in human placentas -

Energywise Ireland open new renewables showroom

Energywise Ireland open new renewables showroom -

Together in Electric Dreams

Together in Electric Dreams -

Major office scheme passes DLR’s passive house or equivalent policy

Major office scheme passes DLR’s passive house or equivalent policy -

BREEAM excellent building marries sustainability with world-class design

BREEAM excellent building marries sustainability with world-class design -

District heating and passive house - are they compatible?

District heating and passive house - are they compatible?