Walking on water

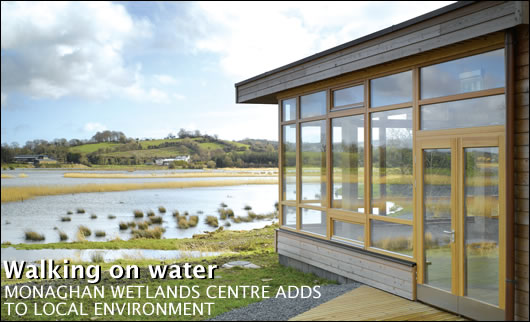

Designing a low-energy public building with passive ventilation and lighting in mind is one thing – making it fit seamlessly into a rural wetland environment is quite another. Lenny Antonelli visited the award-winning Ballybay Wetlands Centre in County Monaghan - a closed-panel timber frame structure designed to sit softly on the surrounding landscape

Environmentalists might shirk at the idea of building along the Ballybay wetlands, an ecologically rich freshwater habitat in central Monaghan. But the new Ballybay Wetlands Centre is no ordinary building.

Constructed from Obweger's closed-panel timber frame system, the 400m2 building was designed to be ventilated and illuminated naturally, and to nestle unobtrusively into the surrounding landscape. Built as a centre of environmental education, the building sits on an old farm outside Ballybay town, and won the best building award at the 2008 national Green Awards.

“The building sits between a clump of trees and another line of trees running up to a hedgerow. To an extent the aesthetic of the building picks up on the idea that it’s a bird hide. It was important to keep the roof profile low in order to reduce its visual impact,” says Mike Haslam of Solearth architects, designers of both the building and a masterplan for the 65 acre site. Haslam was the company partner in charge of the project.

Christina Cassidy, project manager at the centre, says minimising the building's visual impact was crucial. “We wanted a building that would absolutely blend in to the environment,” she says. Cassidy thinks the site looks even better now than before. “That particular site was miserable. There was a lot of rubbish, and it was hard to really appreciate what was out there.”

The Ballybay wetlands are home to bird species such as widgeon, lapwing and curlew, and a key national population of whooper swan. Solearth sought to minimise the building's impact on the local wildlife when designing a masterplan for the 65 acre site.

“We went through a McHargian approach, which is based on the work of Ian McHarg,” Haslam says. McHarg was an influential landscape architect, whose 1969 book Design with Nature pioneered the concept of ecological planning. Under this approach, all aspects of the site's ecology were mapped individually, including surface water, groundwater, and habitats such as wetlands, woodlands and hedgerows.

For each map, ecologically sensitive areas are shaded in darker colours, with less vulnerable spots in lighter tones. “You get an overlay of all the different factors that are analysed, giving you darker areas and lighter areas. The lighter areas are less ecologically vulnerable and suggest the position where you can start to think about building,” Haslam says. “I think it’s one of the most rigorous design documents we’ve done in the office in terms of ecological analysis.”

The wetlands centre is an initiative of the Ballybay Development Association, a community group established in 1995 at a time when the town had 34 derelict buildings on the main street. The group raised e450,000, purchased a derelict building and converted it into commercial units and self-catering apartments.

Cassidy, a former science teacher, thought the group's next project could focus on environmental education. “I thought it would be a really good idea to take the environment into the schools and the schools into the environment. I was looking at the town park for developing allotments or working with local schools and creating activities for kids. And it just happened that this farm came to the market. The BDA said that if it came in at e300,000 they could afford to buy it, and it did.”

The BDA was awarded funding from a variety of sources, enabling it to hire Solearth to design a site masterplan. When the plan was complete, Cassidy applied to Fàilte Ireland for funding to build the centre.

“I wrote the business plan, and they completely rejected the idea of a wetland farm being of national significance,” she says. “I was devastated.” O’Rourke engaged a marketing consultant to assist her with an appeal. She persisted, and was finally awarded e950,000 in September 2006.

The south-facing façade of the centre

A small artificial pool collects rainwater from the roof above. “There’s quite a nice little habitat going on in there,” says Mike Haslam of Solearth architects

The finished building is beautifully simple - a subtle, compact structure with a heterogeneous timber finish that allows it to fit seamlessly into the surrounding landscape. “We wanted a fairly compact form to minimise the envelope for economic as well as energy reasons,” Haslam says.

The centre takes inspiration from the farm buildings that occupied the site previously - particularly an old silage pit. A change in floor level in the new building marks the edge of the old pit. “We thought we could re-use that landform, and use the change in level to mark the difference between the cafe area and the service area at the back of the building,” Haslam says. “That was a circumstance of the site that informed the design.”

The line signifying the edge of the old pit continues outside the building, where it marks the edge of a small artificial pool of water below the south facade that collects rainwater from the roof above. “There's quite a nice little habitat going on in there,” says Haslam.

Solearth's philosophy was to design a building that needed few bolt-on technologies. “We wanted to do a public building passively as much as possible,” he says. “It's about insulating well, a good quality durable finish, and letting the desire for natural ventilation and lighting dictate the form of the building.” The passive lighting strategy reaps most reward in the cafe space to the building's south. Here, an extensively glazed wall lets sunlight illuminate the space naturally, and allows staff and visitors to view the wetlands below. “I love the way they've captured the light,” Cassidy says. “It's like a slideshow every ten minutes the way the lighting changes.”

All of the windows in the cafe can be opened manually, allowing for easy cross-ventilation. Light from the cafe helps to illuminate the main seminar room above too, supplementing a monitor roof light that opens automatically if the CO2 concentration rises above a certain level. The seminar room features a small mechanical extract fan, as does the kitchen, bathroom and certain pubic thoroughfares, though Haslam stresses that low energy fans were specified. Throughout the building, natural light is supplemented by energy efficient T5 fluorescent lamps.

From the inside out, Obweger’s closed-panel timber-frame system features 12.5mm of gypsum fibre-board, 12mm of OSB board, 180mm of rockwool insulation with timber framework, 16m DWD wood fibre-board, an air-tight breathable membrane, 30mm of pressure treated timber battens that forms a ventilated cavity, and external larch cladding, all of which adds up to a U-value of 0.2W/m2K. A Sto render is also used on parts of the building. “The timber is all Austrian, and it’s all from sustainably managed forests,” says Josef Steiner of Structural Timber Systems, Obweger’s Irish agents. Steiner's Furbo showhouse was profiled in the last issue of Construct Ireland.

For Christina Cassidy, timber frame was a method of construction she became familiar with while living in Tokyo. “I became interested in what Gerry McCaughey (founder of Century Homes) was doing in Japan, and the kind of construction they were involved in. I suppose I was interested in new construction and new design. Prior to that I'd lived in the States and it seemed there was great room for different building methods there.”

Solearth considered stick-built (constructed on site) timber-frame too, but time restrictions meant it wasn't possible. “We had to go with prefabrication, which we're happy to do anyway,” Mike Haslam says. “The thing about working with a system from outside Ireland is that you're playing off what you know to be a very durable system, and a very well-built system, against using local materials.”

“I suppose that's the downside in terms of looking at the building from an embodied energy perspective. On the other hand, in this particular case, a trusted, fast contractor was imperative.”

Haslam elaborates: “The other way would have been to use a local builder, or local timber-frame supplier, and do stick-built or open-panel frames. We might have gone down that route if it was a longer contract period, but to be honest I've become quite impressed with the quality of finish from Obweger.”

Katzbeck windows were supplied with the Obweger wall system - the units are double glazed, krypton-filled, and boast two low-e coatings and an overall U-value of 1.3W/m2K.

The larch clad building was constructed using Obweger’s closed-panel timber frame system

An extensively glazed wall lets sunlight illuminate the south-facing café space while enabling staff and visitors to view the wetlands below

The roof is insulated with 260mm of rockwool and finished with an EPDM membrane. “We always avoid PVC when possible, so that's out to start with,” Haslam says. “And then we're looking at greener alternatives like EPDM or polyolefin. EPDM is more benign than a PVC roof. There is an issue about how green these roof materials are, because obviously they're all plastic derivatives. But a roof more than anything else has to perform highly. I think there's a lot to be said for pitched roofs using a traditional material like terracotta - something with low embodied energy and high durability. But in this case, for visual impact we were trying to keep the building low.”

A public viewing platform sits on top of the roof. The building wasn't tested for air-tightness, but Josef Steiner says Obweger buildings typically produce blower door test results of about 0.55 air changes per hour at 50 pascals.

Unipipe supplied a Nibe ground-source heat pump that meets most of the building's heating demand. Six square metres of solar evacuated tubes supplement the pump. “The solar is there to operate as a space heating support as well as providing hot water,” says Paul O’Donnell of Unipipe. “In the winter it can throw in a few kilowatts to cut down the firing hours of the heat pump.”

The building sits on the edge of the Ballybay Wetlands, an ecologically diverse freshwater habitat in central Monaghan that is home to a key national population of whooper swan, as well as other bird species such as widgeon and curlew

“If a building is using 40,000kW of energy per year, only 5,000 to 8,000kW of that will be hot water, so our thinking is that we should try and get what we can from the solar for space heating.”

There are other green features on the site too. FSC certified timber flooring from Kahrs is used throughout. Low flush toilets and Auro natural paints feature too. The car park is paved with Hoofmark's Golpla permeable paving system, a rigid, high quality plastic grass reinforcement and erosion control system, designed to allow the growth of grass and soak up run-off water whilst still supporting vehicles.

The local authority wouldn't allow Golpla in the coach park however. “You're somewhat greeted by a large car park there when you enter, but then it fades out and allows the building to fit within a more natural landscape surrounding,” Haslam says.

A public viewing platform sits on top of the building

Obweger’s closed-panel timber frame system being erected on site

If suitable grants are available, a wall of photovoltaic panels may be installed adjacent to the evacuated tubes, and wind is also being considered. “We identified wind generation and solar power potential as part of the masterplan process, and suitable sites were identified,” he says. “As you move up the hills you've got good wind energy potential.”

There were initially plans to develop an artificial reed bed on site to treat greywater. However, the plan was abandoned when it looked unlikely to gain local authority approval. As well as treating wastewater, a reed bed system could have played an obvious educational role at the centre.

“It’s unfortunate,” Mike Haslam says. “There was a worry about flooding, which is fair enough. That meant the reed bed would have to be located high above the flood line, but there were worries about percolation too. The percolation tests were fine and everything though.”

Ballybay Wetlands Centre from above

Cassidy elaborates: “For some maybe the reed bed was just a step too far. We argued the case and said that a constructed reed bed would reduce the burden on the council to provide a service, and that we'd be self-sustaining in that regard. We were advised that we’d need to apply to Monaghan County Council to get a discharge licence because we’d be discharging into the Dromore river system, and it was suggested it'd be very difficult to get that.”

With or without the reed bed and the photovoltaics or wind turbines, the building is a triumph. One testament to it is that in featuring the building, Construct Ireland had few people to interview and components to write about. The building's simplicity makes it sustainable - the compact form, passive lighting and ventilation, well-insulated structure, and use of natural materials.

A six square metre evacuated tube array contributes to the building’s hot water and space heating requirements

Such a remarkable building should be seen and used by as many people as possible. “We're about providing practical environmental courses,” Cassidy says. “Students from Drogheda IT come here at the moment to do fieldwork. We're going to be running FETAC courses as well.” Cassidy hopes the centre will become a local tourist attraction too. “We've put in one and a half kilometres of walkways, which are designed to take people in to all the different habitats around here. We're also putting in information stations along the way.”

And how does Cassidy feel about the building now? “I love the quirky hallways and the shapes of the different rooms. I love the way they've captured the light. It's magnificent.”

Selected project details

Client: Ballybay Development Association

Architect: Solearth

M & E/structural engineer: Buro Happold

Main contractor: Brendan Loughran & Sons

Build system: Structural Timber Systems

Heating system supplier: Unipipe

Timber flooring: Kahrs

Drainage: Hoofmark

- Articles

- timber

- Walking on water

- low energy

- wetland

- Ballybay

- Obweger

- Solearth

- Rockwool

- golpla

- paving

Related items

-

Timber in construction group holds first meeting

-

Mass timber consultation: have your say by 21 April to change the rules

Mass timber consultation: have your say by 21 April to change the rules -

Seeing the wood for the trees - Placing ecology at the heart of construction

Seeing the wood for the trees - Placing ecology at the heart of construction -

Boxing clever

Boxing clever -

Thinking inside the box - Victorian semi retrofitted as a house within a house

Thinking inside the box - Victorian semi retrofitted as a house within a house -

TU Dublin launches timber technology degree

TU Dublin launches timber technology degree -

Scottish passive house built with an innovative local timber system

Scottish passive house built with an innovative local timber system -

Towards greener homes — the role of green finance

Towards greener homes — the role of green finance -

Sola open new NZEB showroom

Sola open new NZEB showroom -

Channel Islands gets its first passive house

Channel Islands gets its first passive house -

Timber frame & mass timber: the Passive House Plus guide to structural timber construction

Timber frame & mass timber: the Passive House Plus guide to structural timber construction -

Wood works - Sleek but large Herts passive house goes heavy on timber

Wood works - Sleek but large Herts passive house goes heavy on timber