- Insight

- Posted

Flat pack on track

What do you get if you cross a quantum physicist, a forensic accountant, a merchant, an engineer and a software-whizz-kid architect? A terrible punchline presumably. But as Jeff Colley discovered on a trip to Sussex, you get something not to be laughed at: a collaborative approach that may be about to unlock a scalable, highly sustainable, circular economy-proof, flat pack build approach.

This article was originally published in issue 42 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €15, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

A postcard-picture farm in a national park may not be the backdrop you’d expect for cutting edge innovation in sustainable building, but in the case of one exciting new venture, the agrarian focus on growing from nature seems particularly apposite. Because hidden in the sunny, bucolic landscape of the South Downs National Park in West Sussex, a potentially revolutionary approach to house building has emerged under the banner We Build Eco – which effectively offers designers, builders and clients the ability to borrow a factory and skilled team to convert their building designs into a leading edge timber frame flat pack system. Passive House Plus got sneak preview access to the new venture prior to its full launch.

Chloe Hayward and Antoine Costantini have been constructing low energy buildings under the name of Kithurst Homes since 2006, experimenting with a number of build systems ranging from insulating concrete formwork to timber frame. An unassuming man who is disinclined to talk about himself, Costantini’s background is too insightful to ignore. Having worked on passive house projects as part of Plate-forme Maison Passiv in Belgium and Germany, Costantini has a background in quantum physics, the study of matter and energy at the most fundamental level, which aims to uncover the properties and behaviours of the very building blocks of nature. He took this spirit of scientific discovery into his construction, seeking approaches which delivered scientifically robust approaches to energy performance, comfort and durability, while minimising environmental impacts. The more he and Hayward researched, the more they were drawn to approaches founded on timber – albeit where used sparingly.

Chloe Hayward emphasises that while it is possible to make insulated panels in the factory, We Build Eco would rather charge less money and send flat packs out to reduce transport costs and emissions, and to support local economies.

“Building out of logs doesn’t make sense,” says Costantini. “We don’t have the resource and that resource is not for ever. At one point we won’t have enough timber to build all in timber.” Costantini posits the use of engineered timber as a solution. “If I use an I-joist, I can use 40 to 60 per cent less timber. We can build more for the same amount of tree.”

Hayward’s background in forensic accountancy provided a useful corrective to identify approaches which stacked up commercially.

They eventually settled on a panel system whose name riffs off structural insulated panels (SIPs), albeit with more ecological materials – naturally insulated panel products (NIPPs), which Costantini describes as “our core.”

“I designed the NIPPs as a simple system which is always I-joist core,” he says, a system which consists of wood fibre insulated panels with I-joists of variable thicknesses depending on the desired insulation level, and 60 mm of semi-rigid wood fibre insulation to the external to eliminate thermal bridging. “We realised that was the best bang for the buck.” Having elected for an I-beam based structure using wood fibre insulation, it was no surprise that the pair ended up running into Will Kirkman of Ecomerchant, whose broad range of green building materials includes wood fibre insulation and I-joists from German natural materials giant Steico.

Located on a farm in a national park, the factory makes use of extensive PV arrays to reduce manufacturing emissions, such as from the electric Hubtex forklift. (pictured below)

The We Build Eco collaboration also includes that rarest of things – a structural engineer with real expertise in sustainable building, in the form of Beth Williams of Build Collective. The collaboration also extends to a relationship with Charlie Luxton Design, who have made significant contributions in manipulating design software to suit the system to convert 2D drawings into a 3D house complete with a fully detailed We Build Eco superstructure.

“The whole thing about We Build Eco is that it identifies a methodology and production capacity to build,” says Will Kirkman. “In its simplest form: you send us your simplest drawings, we convert them into a We Build Eco house – an I-joist house – which you then get delivered as a kit. You can’t get simpler than that.”

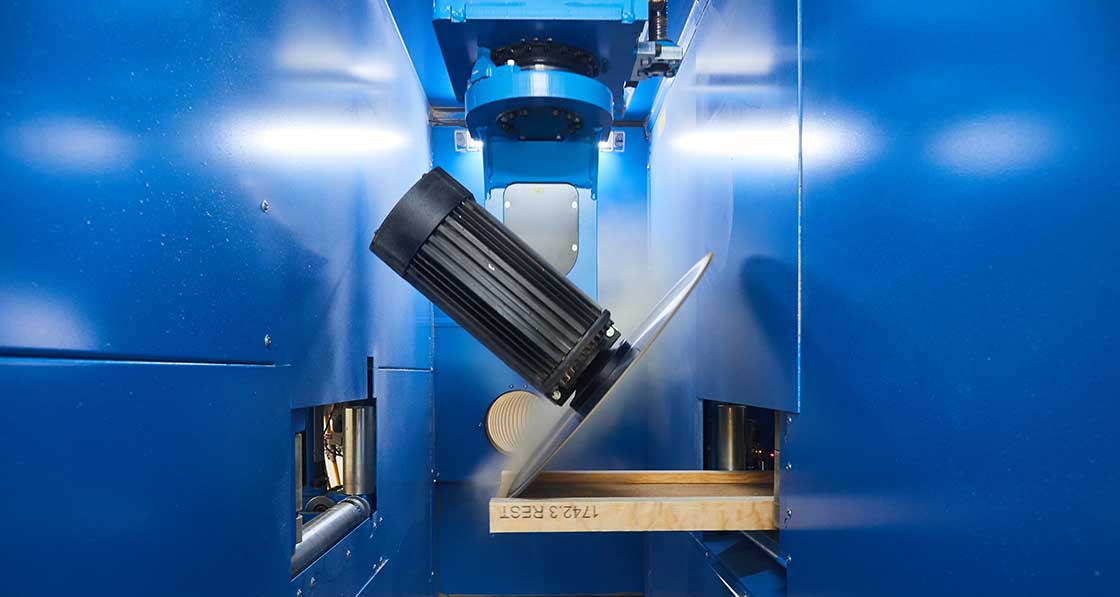

One of the keys to unlocking this simplicity is technology. Kithurst invested in a high tech Hundegger saw to cut the elements for timber frame buildings quickly and with unerring precision. And a major part of the saw’s significance comes in the software which controls it – and the ability to interface with 3D building design software.

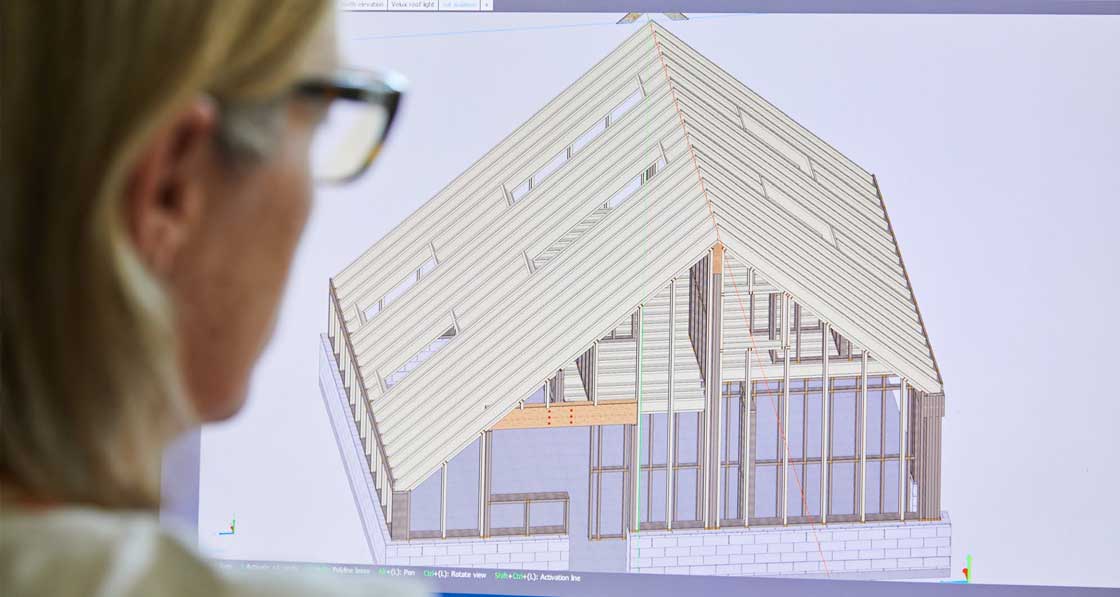

In practical terms, the process typically runs like this: an architect provides 2D drawings for a building, irrespective of what construction method was intended. Costantini uses specialist 3D wood manufacturing software Cadwork, which he has populated with a library of wall, to trace over the drawing. “I can take any drawing – DWG, PDF – put it in 2D and trace over it.”

Utilising the team’s expertise in timber engineering, We Build Eco have discovered a way to translate the drawings into an engineered output and file suitable for use by the cutting equipment. “So I can have all the joists, all the screws, the insulation – everything. That works extremely well.” If the architect already has 3D BIM files, Costantini converts it into Cadwork. “The beauty of that software is it talks the update to my machine. So instead of doing a cut list by hand from an Excel spreadsheet and filling up a BVX [Hundegger] machine file, this thing in two and a half minutes flat will transform it to a BVX file. It goes directly to the Hundegger, and it’s cut, labelled and marked.”

Costantini showed a demonstration of the system to a rapt audience of sustainability-focused construction professionals at a soft launch in June, the saw balletically pivoting to cut timber element after timber element quickly and precisely – to tolerances of between 0.5 and 1.5 mm, depending on the angle the timber is being cut at.

“We do spot checks all the time. To check it’s always in that 1.5 mm tolerance”, says Costantini. If it’s out by more than 1.5 mm, the machine is stopped and a spot check is done to see if something is wrong with the machine or the timber. In the truss industry, roof trusses may be made to 10 mm to 15 mm tolerances, but as a batten is placed on top, it tends not to matter. But part of what marks out We Build Eco’s offering as different is an obsessive attention to detail.

2D drawings are converted into 3D buildings complete with a fully detailed We Build Eco superstructure.

Will Kirkman points out another benefit of an approach which provides a much more rounded design before a tool has been picked up on site: buildability. “The other advantage of this translation process is that it doesn’t allow an architect to design in undeliverable connections and junctions,” he says.

According to Costantini, while most architects are still working in 2D, converting the plans to 3D can provide key insight to prevent problems on site – with one recent project near the factory fresh in his mind. “We got a valley rafter, and it was really tight,” he says.

“In 2D you don’t see the space you’ve got under, and it did not work. On a flat plan it worked extremely well. As I always say, Autocad is beautiful. I can fit a pregnant elephant in a shoebox. In reality, it’s always a bit different and harder. I did it in 3D, I talked to the architect, who came in here, and we went through it and she realised how bad it was and in 3D we found a way to do it.”

“We’ve been asked by architects to build houses where you have a floor plan, an elevation and a section, and nothing works. You’ve got a wafer thin floor with an enormous beam in it, because there’s no integrated design. They don’t talk to each other. The builder gets a bad rep. but actually they’ve saved the backsides of many architects, because they make it work on site.”

When the soft launch event in June was winding down, there was a chance encounter with one of Kithurst’s clients, Alan Brown, who had popped into the yard to pick up some rolls of insulation. A bank fitting contractor of some 40 years vintage, Brown prefaced his words by saying “I’m not eco but,” before launching into gushing praise of a system he was using to build his own house. “You get the sole plate down, you make sure it's all plumb, and that’s it,” he said, still reeling from the fact the system, went up so seamlessly – and with nothing to put in the skip. As Will Kirkman points out, clients learning about this precision are starting to demand more.

“Antoine’s got another customer who was a bit miffed that his roof – with a three way roof with a valley – was 3.5 mm out,” he says.

A novel aspect of We Build Eco is the decision to focus on providing flat pack build systems rather than pre-fabricated panels wherever possible. Chloe Hayward lists two scenarios for how this might work on a housing scheme. The flat packs can be transported to site, with the structures then built on site. Or the developer could find a local warehouse, set it up and they build the cassettes there, transport it down the road and crane it all in.

“You have the choice of either sending it direct to site or to a hub effectively where you have people indoors,” she says. “You might decide: ‘This build is going to be affected by the weather, I’ve got loads of warehousing space empty. I’m trying to create a local project, involve local builders and maybe get some apprentices involved – and maybe it’s just easier to manage in a big warehouse and organise it that way.’”

Hayward doesn’t rule out making the panels in Kithurst’s factory, but only as a last resort. “We could do it here but actually we’d rather do the volume, send the flat packs out, take less money from everyone and make the economy more of a local economy.”

Part of Hayward’s thinking is about transport. “If we create a flat pack and send it out, it means less transportation coming in and out of here because I’ve got one lorry going out as opposed to maybe six or seven. Once they’re made into a panel they take a lot more room and you need a lot more transport. And transport costs are high – it can be £700 for an arctic not that far away. You start adding up the number of arctics you’ve got and it adds up quickly. Plus they have to crane everything. So if they’ve got everything locally, it’s easier than waiting for each delivery.”

Information from the 3D drawings is relayed to the software for operating the Hundegger saw, so that timber elements can be cut precisely to size.

The 5-axis saw unit can be pivoted through 360° and at the same time tilted by 90°.

By way of example, Hayward mentions a flat pack Kithurst supplied earlier that week for passive house build system supplier PH15. All the I-joists and LVL for the 200 m2 house went out on one arctic lorry. “It wasn’t even full actually,” she says.

It’s no surprise that this rounded sustainability consideration extends to other aspects of the business, including how the flat packs are sent out. “We don’t repackage what we’ve cut with plastic." says Hayward. "We send everything out with metal strapping on bearers. And it’s up to the customer to put a tarp on it or something and keep it dry.”

What’s more the build system has been designed with the end of life in mind too, with Costantini saying the whole system is intended to be dismantlable and recyclable. “My idea was that every component is recyclable or compostable.”

This interest in circularity was also another reason why Costantini was drawn to Steico. “I work with Steico for a reason,” he says. They use everything. They shred wood to make insulation. They make LVL, I-joists and pallets made from the centre. Nothing is wasted.”

Will Kirkman emphasises another benefit of Steico’s insulation which may start to gain currency in light of the increasing risk of heat waves: phase shift, or the time between the highest temperature occurring on the outside of a component and the highest temperature on its inside. Recent analysis by Steico UK technical director Martin Twamley showed that build-ups with identical U-values could see phase shift vary from roughly six and a half hours to 14 hours, simply by changing the materials used, such as different sarking boards and insulation. “The whole point is there are areas where natural insulation materials just perform better than synthetic ones, and so that should be the natural default choice,” says Kirkman. “Certainly with any kind of room in the roof – any living space adjacent to the roof – any walls with lightweight construction – the natural insulation material is the one to use. You just don’t want to say to people it’s natural. You want to say to them it is a really good performing building. It outperforms building regs for the same price as one that only complies.”

The system is notable in the conscious decision to eschew plastic. It’s safe to say Costantini is not a fan of the use of plastics or oil-based products in buildings, be it in the form of insulation, windows or gutters etc. He cites a 2019 study which indicated people may be consuming five grams of microplastics per week – equivalent to a credit card. “Using plastic is a deliberate act as part of a systematic campaign which has caused human suffering on a large scale,” he says, There is an openness and generosity of spirit in the thinking behind We Build Eco – in the willingness to share their entire system and processes to all and sundry – an openness which is admirable and necessary, given the need for the whole industry to rapidly shift to building physics-based sustainable building methods like this.

“If you hold your little secret in your hand and you don’t want to share it it’s not going to work, because only a few people will have that lovely golden goose egg, and that’s it,” says Costantini. “What I want is: we don’t talk about natural material anymore in construction because it’s so normal we don’t have to. For the moment, we talk about it because it’s not the norm, and that’s my little war on building, to get people using natural materials. It’s not tricky to use them, it’s no different from other stuff.”

-

Industry professional attendees at the We Build Eco open day were invited to get their hands dirty and make NIPPs for themselves

Industry professional attendees at the We Build Eco open day were invited to get their hands dirty and make NIPPs for themselves

Industry professional attendees at the We Build Eco open day were invited to get their hands dirty and make NIPPs for themselves

Industry professional attendees at the We Build Eco open day were invited to get their hands dirty and make NIPPs for themselves

-

Steico UK technical director Martin Twamley with product and business development manager Daniel Brown pitching in

Steico UK technical director Martin Twamley with product and business development manager Daniel Brown pitching in

Steico UK technical director Martin Twamley with product and business development manager Daniel Brown pitching in

Steico UK technical director Martin Twamley with product and business development manager Daniel Brown pitching in

-

Wood fibre board being screwed to the outer face of the panels

Wood fibre board being screwed to the outer face of the panels

Wood fibre board being screwed to the outer face of the panels

Wood fibre board being screwed to the outer face of the panels

-

in a rare practical moment, Passive House Plus editor Jeff Colley fixing a Vapourblock airtight board to the inner face of a NIPP;

in a rare practical moment, Passive House Plus editor Jeff Colley fixing a Vapourblock airtight board to the inner face of a NIPP;

in a rare practical moment, Passive House Plus editor Jeff Colley fixing a Vapourblock airtight board to the inner face of a NIPP;

in a rare practical moment, Passive House Plus editor Jeff Colley fixing a Vapourblock airtight board to the inner face of a NIPP;

-

Costantini pumped Steico Zell wood fibre insulation into a perspex-fronted NIPP and removes the casing to measure the density of the insulation using an X-Floc NW100 density testing set

Costantini pumped Steico Zell wood fibre insulation into a perspex-fronted NIPP and removes the casing to measure the density of the insulation using an X-Floc NW100 density testing set

Costantini pumped Steico Zell wood fibre insulation into a perspex-fronted NIPP and removes the casing to measure the density of the insulation using an X-Floc NW100 density testing set

Costantini pumped Steico Zell wood fibre insulation into a perspex-fronted NIPP and removes the casing to measure the density of the insulation using an X-Floc NW100 density testing set

-

Costantini pumped Steico Zell wood fibre insulation into a perspex-fronted NIPP and removes the casing to measure the density of the insulation using an X-Floc NW100 density testing set

Costantini pumped Steico Zell wood fibre insulation into a perspex-fronted NIPP and removes the casing to measure the density of the insulation using an X-Floc NW100 density testing set

Costantini pumped Steico Zell wood fibre insulation into a perspex-fronted NIPP and removes the casing to measure the density of the insulation using an X-Floc NW100 density testing set

Costantini pumped Steico Zell wood fibre insulation into a perspex-fronted NIPP and removes the casing to measure the density of the insulation using an X-Floc NW100 density testing set

https://passivehouseplus.co.uk/magazine/insight/flat-pack-on-track#sigProIdcf931094b8

What is the We Build Eco system?

Kirkman is at pains to point out that the We Build Eco system shouldn’t be conceived of as a proprietary system in the conventional sense. “The issue we see in the marketplace – the bit people struggle to do is to get someone to build what they want to their designs. This is effectively a factory for rent that builds an I-joist system. Once the engineering is agreed, the process becomes about making their product for them.”

Kirkman foresees developers, builders – even timber framers who are selling beyond their capacity – using We Build Eco on their projects, and even taking their clients to visit the factory. “We are really just skilled employees who are not on your payroll,” he says.

The full build up from inside to out includes an airtight layer (either an airtight racking board such as Durelis Vapourblock or – more typically for roof panels – a paper membrane), an I-beam – available, depending on how much insulation is required, in widths of 160, 200, 240, 300, 360 or a whopping 400 mm . The void is then filled – typically with Steico Zell blown wood fibre insulation, though Steico Flex is also possible, as indeed is blown cellulose insulation.

In the case of walls, the system will require a membrane, but the roof may not. “There will normally be an internal membrane required in the roof – either Majrex, Intello Plus or Constivap,” says Kirkman. “The Vapourblock will do the job in the walls. And that’s where We Build Eco stop.” The partnership has stopped short of appointing a membrane partner, to give customers the flexibility to work with a membrane they’re comfortable with. “I don’t think we’d bring in a membrane partner for that reason,” says Hayward. “Because we all have different preferences about applications.“

The system is finished to the external with 25 to 50 mm battens, depending on the cladding type. The partners are also open to working with different window suppliers. “This isn’t the kind of collaborative attempt where everybody’s looking to make a bit of money on everything,” says Kirkman. “It’s the core service, the core provision is costed out with everybody with a margin in it. We’re quite happy with that thank you very much.”

Brexit has made it harder to export the system for tax reasons, though Hayward explains that they are set up to deliver in Ireland too, albeit without supplying the insulation.