- Insight

- Posted

How to rescue retrofit

Progress on retrofitting Europe's building stock is sluggish, but there is a way out of the mire.

Is the green new deal dead — or was it ever even born? After western economies tanked in 2008 the idea of green economic stimulus had its heyday.

Making our buildings drastically more energy efficient was at the heart of the plan. We could kill five birds with one stone: cut carbon emissions, make homes warm, slash energy bills, create jobs and kick start sluggish economies.

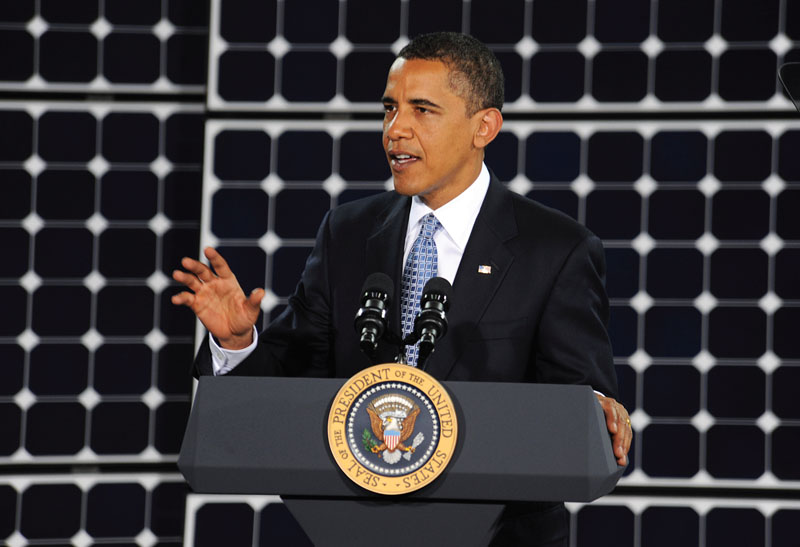

In the US, then presidential candidate Barack Obama promised to create five million "green jobs". His first stimulus bill as president even backed this up with $90 billion for green projects.

The British prime minister Gordon Brown said the economic crisis was "an opportunity to tackle our over-dependence on oil and to meet our three interlinked objectives – energy security, climate change and job creation – together."

His successor David Cameron took over promising the "greenest government ever." In 2010, the Irish government announced plans to upgrade one million buildings within a decade1.

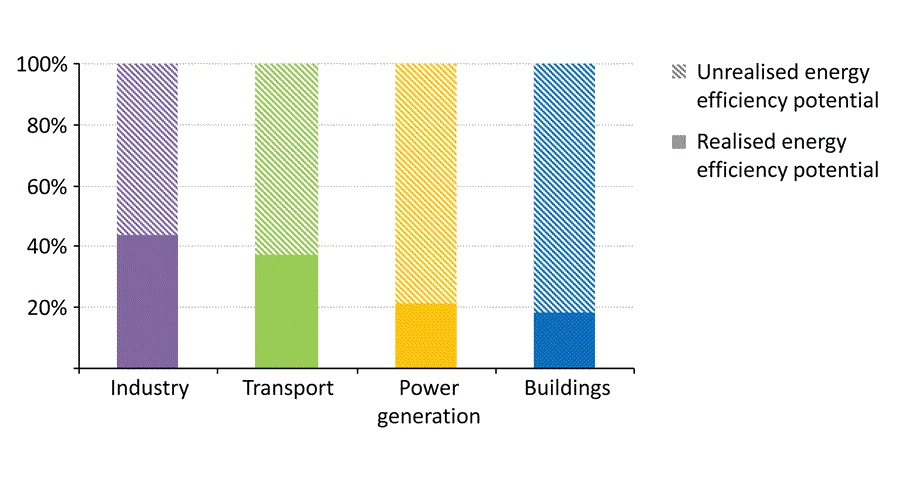

But progress has been stagnant. The International Energy Agency says 80% of the "economic potential" of energy efficiency in buildings remains untapped2.

In Europe we renovate just one per cent of our buildings each year3. "This is just not enough, it's not ambitious enough for the future," says Adrian Joyce of Renovate Europe, a retrofit campaign backed by big companies in the energy efficiency sector. "We're just not doing enough renovations, and the renovations we do are not deep enough."

England is now without a government-funded home insulation programme for the first time since 1978. The coalition government has killed Warm Front, which provided insulation and heating grants to low income households. Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland continue with their equivalent schemes.

One of the programmes that has replaced Warm Front is the Green Deal, which offers retrofit loans that homeowners pay off through their energy bills. The programme's 'golden rule' aims to ensure that savings on energy bills equal or outweigh the loan repayments (though this is not guaranteed).

"The golden rule is rationally a very good idea, but in reality is not going to work," says Adrian Joyce. "If you're only going to consider the rate of payback as the sole criterion, you're almost always only going to have shallow investments."

Even the UK Department of Energy and Climate Change's own assessment expects the number of loft and cavity wall insulations to plummet by 83% and 43% respectively in the first year of the Green Deal and its sister policy, the Energy Company Obligation4.

Financed by energy companies, the ECO will fund energy efficiency measures in low income households and harder-to-treat properties.

But energy companies will inevitably gather the funding by adding to fuel bills. This will make the scheme regressive, says Andrew Warren of the Association for the Conservation of Energy.

"Poorer people will end up paying a greater proportion of that and will not necessarily be benefiting," Warren says. Essentially, all billpayers will pay the same tariff regardless of income, and while all fuel poor bill payers will help fund the scheme, not all will benefit from energy upgrade measures.

The UK government is obliged to eradicate fuel poverty in England and Wales by 2016, under a law passed in the early days of Tony Blair's government. But this is now virtually impossible: research suggests there are nearly eight million people in fuel poverty in England, and this is expected to rise5 as the government cuts funding to tackle it6.

In Ireland, retrofit is in limbo. The current government came to power in 2011 promising to double funding for home energy efficiency and renewable energy until 2013, and to insulate all public buildings in the state via pay-as-you-save.

Neither commitment has materialised. The government has cut its Better Energy heating and insulation grants twice since 2011. It slashed the programme's budget from €76m in 2012 to €50m in 20137, but has promised a new €35m "energy efficiency fund".

The number of Better Energy measures approved — a good indicator of the number of applications— fell from over 160,000 in 2011 to less than 65,000 in the first 11 months of 20128.

The Better Energy Warmer Homes scheme, which funds energy efficiency upgrades to the homes of the elderly and vulnerable, upgraded over 37,000 houses in 2010 but only around 14,000 last year (including about 2,000 in a new area-based pilot that aimed to tackle clusters of houses)9.

Energy minister Pat Rabbitte recently told the Irish Times that while 5,500 people were employed due to government retrofit programmes in 2011, the figure for 2012 could be up to 1,000 less.10

Ireland's goal is to upgrade one million buildings by 2020, almost all of which will be dwellings. But the rate of activity needs to pick up because the country is currently upgrading 50,000 to 60,000 homes a year, according to the National Economic and Social Council11. The vast majority of upgrade measures are shallow ones too, focusing heavily on low cost measures like cavity wall and loft insulation. NESC says there is an "urgent need to bring forward new measures" to meet the targets.

So how do we turn things around? Two recent reports illuminate the way forward. Oxford University’s fuel poverty expert Brenda Boardman's Achieving Zero offers a devastatingly simple set of policies that, she says, could make all buildings in the UK zero carbon by 205012.

Here are just a few of them: Introduce energy standards for existing buildings, and then raise them over time. Require all homes and businesses to have an energy rating. Get building control officers to act as low energy "mentors" on construction projects. Develop low carbon zones in each local authority to tackle clusters of fuel poor households. Phase out grants and replace them with subsidies to make energy efficiency loans more affordable. Reduce taxes on energy efficient goods, and on energy efficient properties. Introduce scrappage schemes for old appliances.

Boardman also says it’s essential to her plan that energy efficient properties become worth more than energy inefficient ones.

Ireland has already taken a step towards this by making it mandatory to display a property's energy rating anywhere it is advertised for sale or rent in an admirably strict interpretation of a requirement in an EU directive.*

Meanwhile, research by the consultancy Copenhagen Economics, commissioned by Renovate Europe, identifies ways to smash some of the main barriers holding back retrofit13.

First, allow landlords and tenants to split the gains from energy efficiency projects — right now, the 'split incentive' means that landlords must pay to upgrade rented properties but don't enjoy any of the benefits, so they have little incentive to invest. (Ed. – The new requirement to advertise energy ratings should help make energy efficiency a key factor in the rental market, by exposing would-be renters to each property’s energy rating before they’ve formed an opinion about the property – before they’ve even read the property listing, never mind set foot across the threshold.)

Second, reform public accounting rules so state bodies can get financing for retrofit. At present many public bodies must put the full cost of an upgrade on one year's budget — at a time when public budgets are under severe pressure. They are often forbidden from counting post-upgrade energy cost savings in their budgets too.

Third, reduce or remove tax breaks and subsidies on fossil fuels, which discourage investment in energy efficiency.

And finally, develop smart risk-sharing programmes like energy performance contracting. Banks have little experience calculating the risk involved with energy efficient investments, so may be reluctant to lend. Retrofit projects often demand big up-front investment, which implies big risk. Energy performance contracting, under which a utility aims to ensure that energy cost savings pay for the retrofit, helps to manage that risk.

But a bigger culture change is needed too. Despite economic meltdown, governments are still reluctant to intervene too heavily in their economies, and are wedded to austerity over growth and investment.

Last October, the United Nations said that breaking the "vicious cycle" of rising unemployment, austerity, fragile banks and deleveraging demanded "shifts away from fiscal austerity�towards job creation and green growth"14.

But what might this shift look like? Last year, Passive House Institute director Wolfgang Feist proposed an "energy revolution" for Europe. With €400bn of investment Europe could trigger €3 trillion of private funding and cut the energy use of all its post-war buildings by 85%. This would create 2.2 million jobs, save 530 million tonnes of CO2 and trigger four trillion euro in energy cost savings, according to the institute. But Feist said it's crucial that such a programme only support deep retrofit projects, otherwise it will just cement poor energy efficiency into the system15.**

Retrofitting fuel poor homes also creates more economic growth than cutting VAT or fuel duty, and creates more jobs than spending on other capital projects, according to research by Cambridge Econometrics and the climate change consultancy Verco16.

Of course, you might expect groups like the Passive House Institute and Renovate Europe to push for a massive energy efficiency drive. But the International Energy Agency, hardly a bastion of green thinking, offers a similar vision in its latest World Energy Outlook.

The report models what would happen in an 'efficient world' scenario, in which all "economically viable" energy efficiency measures — policies that pay for themselves within a reasonable timeframe — are implemented for buildings, transport, power and industry between now and 2035, and all market barriers to their introduction are removed17.

None of these policies would be particularly onerous or expensive to implement — they just demand political will.

In this scenario, governments bring in tough energy standards for new buildings — and those undergoing renovation — and keep pushing them upwards. Minimum energy standards and labelling schemes apply to all energy-using equipment. There are more, and deeper, retrofits as governments remove barriers to action. Old industrial equipment is retired early and replaced by the most efficient technology. Tough fuel economy rules, energy labelling and incentive drives demand for the most efficient road vehicles. New efficiency rules for power stations come into force, and more support is given to combined heat and power and technology. Smart electricity grids become the norm.

All of these ideas pay for themselves within strict time periods. For buildings, this means 14 years for heating measures, and three years for electrical ones.

The IEA modelled the economic consequences of making their 'efficient world' scenario a reality. It admitted this is an exercise filled with uncertainty, but is confident the benefits far outweigh the costs.

Here's what the IEA says happens in their 'efficient world': Demand for oil peaks by 2020, then declines. Demand for coal falls too, while demand for cleaner natural gas rises. Energyrelated CO2 emissions peak by 2020 and then falls. Universal access to modern energy becomes easier to achieve, and local air quality improves, particularly in India and China. Demand for energy grows much more slowly. The world's cumulative economic output increases $18 trillion dollars up to 2035.

But Adrian Joyce of Renovate Europe says policymakers need to look even further, to the less quantifiable benefits of living in warm, comfortable, properly ventilated homes, to factors such as indoor air quality, productivity, and even happiness.

"These things count in people's lives, but it's hard to put them on a sheet of paper. They're not taken into account in what are cost optimal measures, and in our view they ought to be," he says.

The Copenhagen Economics study found that savings from lower healthcare costs and greater worker productivity can account for around half the economic benefits to society of retrofit, though it admitted such calculations are fraught with uncertainty18.

But this points to a new way of thinking about the advantages of energy efficient buildings that looks at more than just fuel bills. Adrian Joyce says he's constantly touting the need to consider indirect benefits like health when evaluating the benefits of retrofit. "It piques the interest of people, but I wouldn't say it's getting traction yet," he says.

"But I'm beginning to feel we're softening the resistance."

*Ireland’s actions are simply a strict interpretation of Article 12 of the Recast Energy Performance of Buildings Directive, which states that the energy performance of a building must be included in “advertisements in commercial media.” Every EU member state was obliged to enact this requirement in law by 9 January, with no derogations possible

**Passive retrofit projects may also be less likely to cause a rebound effect, the phenomenon whereby energy upgrades encourage occupants to use more energy by lowering their bills. It is usually too expensive for building occupants to adequately heat all of a highly energy inefficient building. Once that building is upgraded to be moderately efficient, it suddenly becomes easier and more affordable to heat all of it. But if a deep or passive retrofit is undertaken, there is likely to be much less of this "comfort taking" as heating the building any further will not make it more comfortable. Research by the Passive House Institute suggests that for retrofit, the actual energy consumed is very close to that projected. See the series of articles on retrofit & refurbishment at http://passipedia.passiv.de)

1 National Energy Retrofit Programme Consultation Document, Department of Communications, Energy & Natural Resources (Ireland), 2010

2 World Energy Outlook 2012, International Energy Agency, p290 & 291

3 Europe's Buildings Under The Microscope, Buildings Performance Institute Europe, p103 & 104

4 Final Stage Impact Assessment for the Green Deal and Energy Company Obligation, Department of Energy & Climate Change (UK), p148 & p166

5 Getting the Measure of Fuel Poverty, John Hills, Centre for Analysis of Social Exclusion, 2012

6 The Impact on the Fuel Poor of the Reduction in Fuel Poverty Budgets in England, Association for the Conservation of Energy, 2012

7 Correspondence with Department of Communications, Energy & Natural Resources

8 Better Energy Homes statistics, www.seai.ie

9 Correspondence with SEAI

10 Rabbitte insists he is a good fit for his department and is excited about future, Irish Times, 4 January 2013

11 Towards a New National Climate Policy: Interim Report of the NESC Secretariat, National Economic and Social Council, June 2012m p86 & 87

12 Achieving Zero: Delivering Future Friendly Buildings, Brenda Boardman, Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford, 2012

13 Multiple Benefits of Investing in Energy Efficient Renovation of Buildings: A Study by Copenhagen Economics, Renovate Europe, 2012

14 World Economic Situation and Prospects 2012, Update as of mid-2012, United Nations

15 Master plan for the European Energy Revolution, presented at 2012 International Passive House Conference. www.passiv.de

16 Jobs, Growth and Warmer Homes: Evaluating the Economic Stimulus of Investing In Energy Efficiency Measures in Fuel Poor Homes. Final Report for Consumer Focus. Cambridge Econometrics & Verco, October 2012

17 World Energy Outlook 2012, International Energy Agency, p35

18 Multiple Benefits of Investing in Energy Efficient Renovation of Buildings: A Study by Copenhagen Economics, Renovate Europe, 2012