- Insight

- Posted

Quantifying the greenness of construction products: the rise of environmental product declarations

Climate breakdown and global ecological crises mean that our efforts to make buildings sustainable must go far beyond operational energy use – including number crunching and drastically reducing environmental impacts of building materials. John Cradden reports on progress in the uptake of the building blocks of life cycle analysis of buildings: Environmental Product Declarations.

This article was originally published in issue 30 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

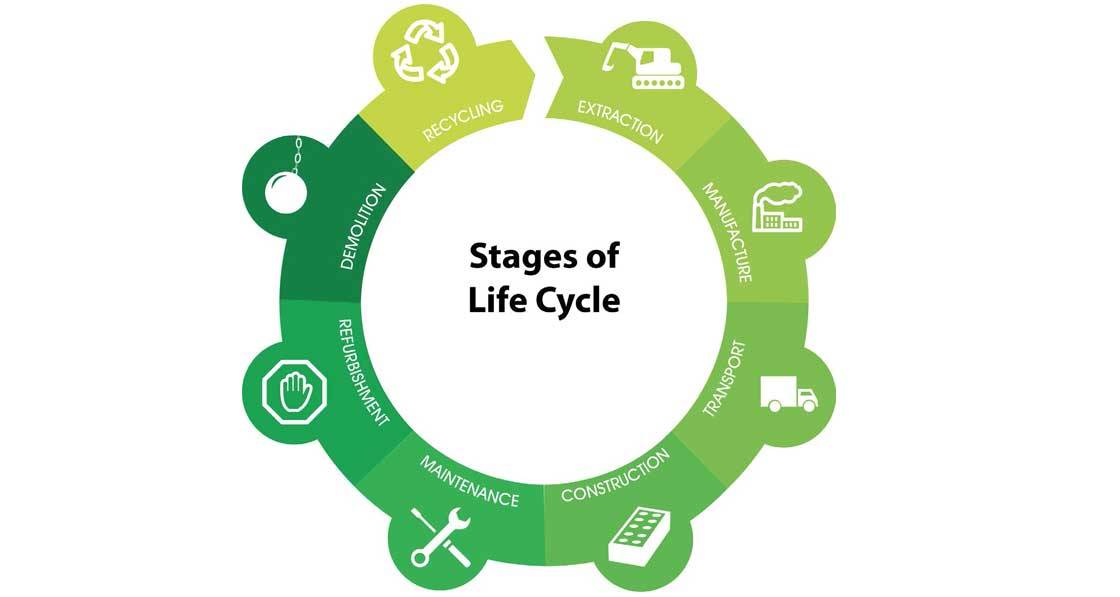

Amid today’s concerns about climate change, the importance of assessing the environmental impact of buildings at all stages of their lifecycles is starting to gain mainstream acceptance. After all, besides the energy and carbon needed to operate, heat and light a building, the materials to construct it must be quarried, mined or harvested; transported to factories and manufactured; then transported to sites, lifted into place and fixed into position. And over its expected lifespan, a given building will need maintenance, repair and replacement before eventually getting demolished and all its components disposed of, whether that’s through landfill, incineration, recycling or re-use.

To date, it hasn’t been particularly easy to calculate the embodied carbon footprint of the materials used in construction, making the already complex job of doing a building life cycle assessment (LCA) somewhat more onerous.

This is where Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) come in. These are a standardised way of providing data about the environmental impacts of a product through the product’s life cycle.

It’s not in itself a ratings system; a product with an EPD is not automatically a product with a low environmental impact. The EPD only provides the relevant data about the product that you can compare with other products at the building level in order to determine its environmental impact.

“It basically gives you the numbers,” said Jane Anderson, an expert in building life cycle assessment and EPDs. “It doesn’t tell you whether the numbers are good or bad, but it does give you the numbers consistently. So then you can take two EPDs and intelligently look at them to see how those products compare.”

However, manufacturers who obtain an EPD will also receive a special EPD report which explains the sources of impacts through the life cycle and enables them to consider how they might best reduce them. EPDs are also helpful for architects, local authorities and governments in getting good scores for their projects in building rating and assessment schemes like LEED, BREEAM and the Irish Green Building Council’s Home Performance Index.

All of which means that EPDs look set to enter the mainstream of the construction industry as it looks to green its output in response to global issues like climate change.

Products with environmental product declarations through EPD Ireland include (clockwise from left) Ecocem cement, KORE EPS insulation, Munster Joinery windows, Quinn Lite thermal blocks and Smartply ProPassiv OSB

In Europe, EPDs must conform to two standards: European standard EN 15804 and the international standard ISO 14025, which means that all EPDs should use a common methodology, use a common set of environmental indicators and have a common reporting format.

An EPD will show the impact of construction products over four life cycle stages: manufacturing, construction, day-to-day use and end of life.

It will also report seven environmental impact indicators: global warming potential, acidification, eutrophication, stratospheric ozone depletion potential, photochemical ozone creation potential, and two types of abiotic depletion.

Pat Barry of the Irish Green Building Council, which operates the Irish EPD programme, acknowledges that the global warming potential is the big one. Other factors like the amount of resources that go into making a product and the scarcity of materials are important, but the focus for now will tend to be on the carbon footprint.

“There is a need to educate the market on embodied carbon, so this is part of a longerterm strategy for us to do that. The IGBC program is intended to generate the data, and our next step is to get people using it.” As you would expect, EPDs have to be independently verified, usually by a third party. Anderson works as an independent verifier of EPDs for a number of the European programmes, including Ireland, Germany, Norway and Sweden.

She agrees that the EU has been the driver of efforts to harmonise standards for EPDs throughout Europe but also worldwide.

There were EPD programmes in the UK, Holland, Sweden and Germany, but “they all had different rules, different indicators and different approaches, and it literally meant that manufacturers were having to do completely different studies in each country if they produced a product that was exported”. “It was the European Commission that then gave CEN, the European standards body, a mandate to harmonize the approaches and to produce a European standard at both the products and building level.”

There are, of course, EPD programmes outside the EU, including in the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand, but they have all adopted the European standard as the basis for their schemes.

EPD growth

According to 2019 data compiled by Anderson, there are now over 6,000 EPDs for construction products that conform to EN 15804 worldwide. So while there has been “strong but not exponential growth” in the adoption of EPDs, Ireland and the UK are somewhat behind the curve compared to other European countries, particularly France and Germany. France has over 2,000 published EPDs between two different programmes, closely followed by Germany with just over 1,300, and Norway with over 500.

“Basically, France has environmental regulation that says if you want to make an environmental claim about the products in France you have to have an EPD to justify it,” said Anderson.

“There’s no obligation to make an EPD, but if you claim your product is low impact, or it’s got a low carbon footprint, or it’s better than somebody else’s, then you have to basically have an EPD. That’s kind of driven the numbers there.” Anderson adds that France has pilot regulations and requirements to reduce the embodied carbon of buildings and increase the use of renewables. “So, there’s a kind of driver in two directions,” says Anderson. “There’s a quite rapid growth there.”

In Germany, there is a widely adopted building lifecycle assessment scheme that requires the use of EPDs, which has driven uptake there, while over in Norway, take up is being driven by both the public authorities and the widespread use of BREEAM, along with what Barry describes as a “very advanced” lifecycle assessment scheme. At the time of writing the UK has 168 and the Irish programme (which in fairness was only launched by the IGBC in 2017) has 15. Of course, relatively few construction products are manufactured in Ireland, with just five companies having published EPDs through the Irish programme covering a select range of products, according to Barry, but there are about 500 imported products with EPDs available in Ireland that have been published through other programmes such as the IBU in Germany or the BRE in the UK.

One other driver of the take up of EPDs is a European Commission initiative called Levels, a voluntary reporting framework which aims to provide a set of indicators and common metrics within the EU for measuring the performance of buildings along their life cycle. This is something that Barry says should drive transparent data for EPDs because “it kind of incentivises quality data”.

Software tools

While all this might sound like another layer of bureaucracy and paperwork to many in the construction sector, the good news is that there is software available that can make producing an EPD much easier. The IGBC, for instance, teamed up with leading Finnish LCA experts Bionova to allow building professionals to quickly calculate the embodied carbon in a building through their One Click LCA software. The web-based application takes the legwork out of calculating a full LCA, reducing the time to a matter of hours rather than weeks and is now more akin to working out a BER.

Panu Passusen of Bionova says a bit of training is required to use the application, “but it is as much training in LCA concepts as in the use of the software”. Training can be included with licences. Users can hit the ground running after 2-hour training for building level studies, while for EPD studies one day is required.

Making the process easier is also crucial to drive the registration of EPDs, as Anderson points out that the figures she compiles do not include EPDs that are not registered or published in any programme. She has used software tools for calculating LCAs and EPDs, including one time with British Precast, the trade association for precast concrete manufacturers and suppliers, to produce an EPD for the average aircrete block and for the average hollow core floor. “All of their manufacturers can actually use that tool to produce an EPD for any of their products... they can use those tools to produce EPDs on demand and the tools have been verified, so there are lots more EPDs that are around that but aren’t registered with an EPD program.”

Of course, it you take a lock manufactuer like Assa Abploy, who have 10,000 different products, then it’s not financially viable or practical to produce EPDs for all of them, so it may only make sense to register the significant ones, she says.

“So, there’s a balance between trying to make sure you’ve got significant products registered and that you can produce them if you need to.”

Pictured with their EPD certificates are (far left) Jason Martin of Quinn Building Products; (left) Munster Joinery’s Marlene O’Mahony; (right) EPA director Eimear Cotter; and (far right) IGBC CEO Pat Barry.

Role of architects

However, there is still a bit of the chicken and the egg regarding the promotion of EPDs; it’s clear that architects need to play a bigger role and start asking for them, says Barry. “We get it all the time from manufacturers that they do not produce any EPDs because they do cost money and because architects don’t ask for them. So the key issue is that architects aren’t aware of them or why they should ask for them.” Two exceptions in Ireland are Dublinbased practices RKD Architects and Coady Architects.

Simon Keogh at Coady Architects says that it recently used more than 25 products on a 20-unit development in Rathdrum without knowing they had EPDs but is now aiming at using 50 products with EPDs on a 42-unit project in Kilbride without any issues over cost or procurement. However, he does believe there is work to be done in pushing product manufacturers to get moving on EPDs in a timely manner, and also to deliver training in LCA software to make use of EPD metrics.

Coadys is also working on completing one of the first - if not the first - building LCA in Ireland in Rathdrum in conjunction with Technological University Dublin. Matthew Reddy of RKD says his firm’s exposure to EPDs initially arose from projects that were seeking LEED or BREEAM project certification. “In these green building certification schemes, credits are available when project teams specify products with third party-verified EPDs.” After a bit of market and product research, the firm opted to focus on products that were independently verified and meet the EN and ISO standards. “From this research we developed a database of products which align with typical material specifications for a range of building typologies.”

Manufacturers

Ecocem has recently updated its EPD for its cement to show a 24pc reduction in embodied CO2 emissions compared with its previous certificate. To put this in perspective, the carbon footprint of cement is approximately 850 - 900kgCO2/t (Ecocem’s GGBS at 32kg of CO2 is approximately 96pc lower).

Ecocem’s Micheal McKittrick, recently appointed managing director for Northern Europe, notes that there are options in the market to significantly reduce the embodied footprint of cement.

“The most effective way to demonstrate that is via EPDs, which are governed by EN 15804. If we want to feed the changing atmosphere on life cycle assessment, the EPD is the single most effective means in doing that”. McKittrick believes that regulation needs to be given more teeth to drive building life cycle analysis here, to reflect the practices elsewhere in Europe such as Holland and France.

Andrew Butler of KORE says his firm started working on creating its EPD for its EPS board in 2018 after the launch of the Irish EPD programme by the IGBC, and published it just last February. Although there was quite a bit of work involved, including breaking down all the parts of the manufacturing process and analysing them, the company was able to learn quite a bit of useful information in the process, he said. This information was used to enhance production efficiency, and gain greater control over the use of secondary materials like water and packaging. “Staff at KORE gained a more rounded knowledge of the impact on the environment of what we do.”

Butler says KORE’s products conform to other EN standards that include strength, dimensional stablility and water absorption, but the EPD is the “first independentally verified method to allow us, as a manufacturer, to share transparently our product information with the construction industry while helping them look to the future”.

Irish wood panel product manufacturer Medite Smartply supplies a wide range of products and has an EPD for every one of them. The fact that some of them are a variation on a base product could have feasibly allowed them to do an EPD just for this base product, but they chose not to. For example, its OSB3 board is the base sustrate for its Site Protect, Propassiv, and Pattress Plus products, but “each has a slightly different finishing process, e.g. coating or machining, which will alter the carbon footprint, and only very slightly, but we want total transparency,” said David Murray of Medite Smartply.

But what probably helps is the use of a new LCA software application made by Dutch firm Ecochain.

“As well as providing us with LCAs and EPDs for our entire MDF and OSB product range, the Ecochain tool allows us to benchmark, monitor and reduce our greenhouse gas emissions as we continually invest and modernise our processes,” said Murray. “We can also analyse the environmental impacts of the materials we purchase, so that they, too, can be substituted by lower impact materials when the opportunities arise.”