- Insight

- Posted

The housing crisis - what is to be done?

Almost a decade after the economic crash, every political party in Ireland now recognises the country is in the middle of a full-blown housing crisis. Similar problems exist in the UK market, but for different reasons. Now, if the political will to fix things has finally arrived, the question remains — what can actually be done about it?

Ireland’s housing crisis has been making headlines this year, whether due to the deaths of homeless street sleepers or the growing sense that not only is home ownership an impossible dream, but that even private rentals are thin on the ground.

Even Ireland’s political class, buoyed for decades by rising house prices as an index of wealth, is finally sitting up and taking notice.

Taoiseach Leo Varadkar recently mooted doing away with Dublin’s height restrictions to allow for high-rise development, as well as, controversially, a return of the late, unlamented bedsit.

“There is a housing crisis in Ireland, and while you are in a crisis situation you approve policies and do things that you wouldn’t do if there was not a crisis,” he said.

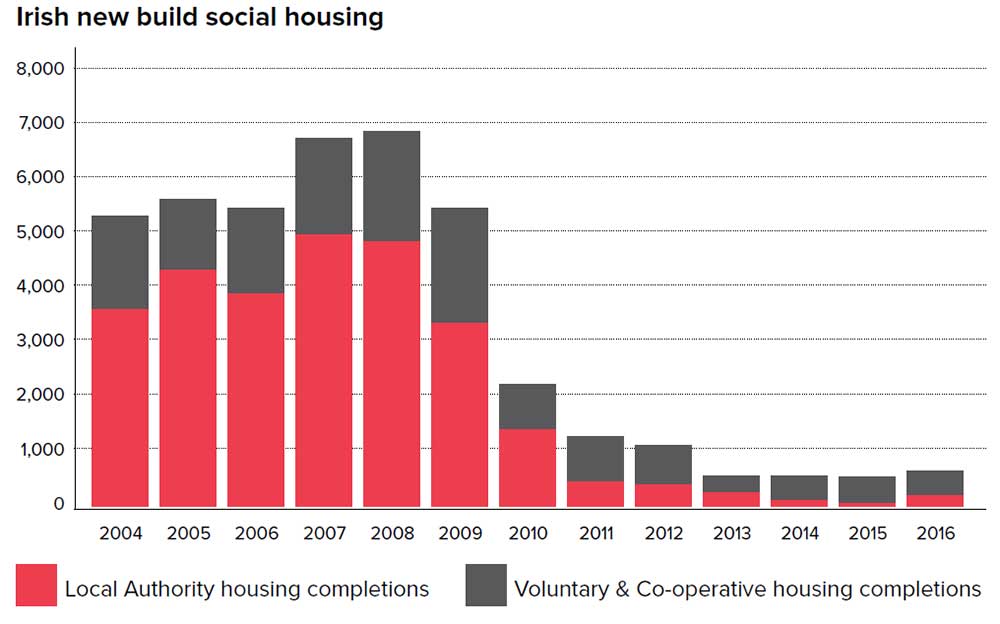

Graph showing the decline of new social housing construction in Ireland between 2004 and 2016

Graph showing the decline of new social housing construction in Ireland between 2004 and 2016

Housing minister Eoghan Murphy has said that this year Ireland will build quadruple the number of social housing units that were built in 2015, but with more than 90,000 people on the housing waiting list it is hard to see how even that – or the pledged 3,800 new houses next year – will make a dent.

As Irish Times commentator Fintan O’Toole recently noted, by 2015 only one per cent of GDP was spent on public housing. Meanwhile, 21 designated ‘rent pressure zones’ have been created in order to cap rent rises in the private sector.

It seems an absurd situation: during the boom years it looked as though the entire Irish economy was based almost solely on building houses, and yet today completions are at a low, causing prices to rocket.

According to figures compiled by economist Ronan Lyons for property website Daft.ie, average prices in Dublin have risen by 60 per cent since 2012. Meanwhile, according to figures from the Real Estate Alliance Average House Price Index, a three-bed semi-detached house in Dublin now costs over €400,000.

The private rental market is also notoriously overheated, with high prices and severe shortage of units. The average monthly rental on a one-bedroom apartment is now €1,422 in the city centre, and €1,145 further out. A three-bedroom apartment in the city, meanwhile, will cost you €2,544 per month.

And that is assuming you can find one. Or that it meets even minimum standards for habitation.

According to Dr Lorcan Sirr, lecturer in housing at the Dublin Institute of Technology, the seeds of the current crisis were sown not during the boom years, but as far back as the 1980s.

“That was the sea change,” he said. “The change of the funding model from local authorities borrowing [in order to build] to getting central government grants.”

This change in funding model accentuated the housing boom to come, he says, and did so by cutting away at the social housing security net.

Sirr does see potential for improvement, however, precisely because the problem is now so bad that it is recognised across the political spectrum.

“Never mind social housing, you have an affordability issue, and that’s hitting the traditional Fine Gael voter and their sons and daughters. It’s not an issue just for poor people. The people who would have voted Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil before now have more in common with people who would be far to the left of them,’ he said.

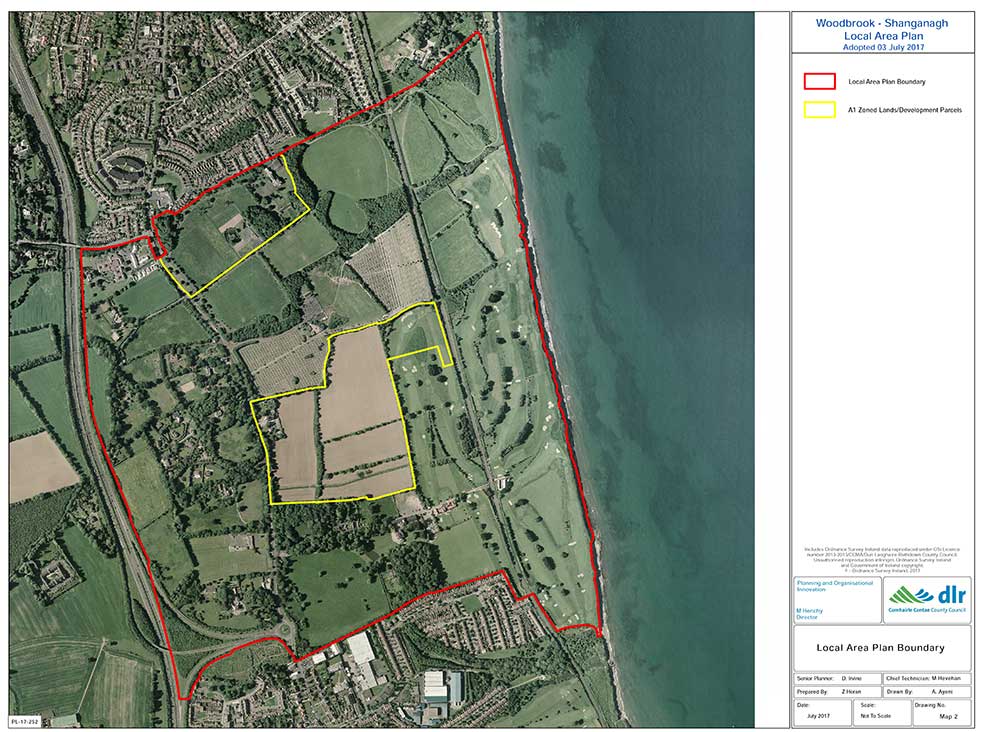

A map from the Woodbrook-Shanganagh Local Area Plan, where Dun Laoghaire- Rathdown plans to build 540 units alongside 1,000 privately developed homes.

A map from the Woodbrook-Shanganagh Local Area Plan, where Dun Laoghaire- Rathdown plans to build 540 units alongside 1,000 privately developed homes.

As a result, the political reality is that everyone is saying something must be done but no-one is quite sure what.

Sirr says that the banks will have to get on board and change their model, otherwise they will have no customers in coming decades.

“The banks are a huge part of the problem and will be a huge part of the solution. Their mortgage business will collapse if things keep going this way,” he said.

One recent idea floated by the government has been the transformation of Ireland’s ‘bad bank’ Nama into an agency to develop housing. Certainly, Nama, a legacy of the 2008 crash, has major land assets, so handing this land over to local authorities to develop social and affordable housing can’t hurt. At the very least it recognises that land banking is a major problem – and one of the primary causes of Ireland’s housing crisis.

For instance, one developer alone, Cairn Homes, controls around twenty per cent of the zoned, un-used land in and around Dublin. Cairn is not alone, of course, but many developers like it complain that they cannot profit from building while sitting on land left unused.

Last year’s housing completions totalled 15,000 nationwide, but, in fact, only 5,000 new homes were built, with the rest being reconnections to the grid of vacant properties. This over-counting is a major issue when it comes to getting to grips with the depth of the housing crisis.

“Between 2011 and 2016 we only added 8,800 [dwellings] to our stock, and, at the same time our population increased by 170,000,” said Lorcan Sirr.

Some more concrete moves have been made, however. One is a new model for development proposed by Ó Cualann Cohousing Alliance.

Longstanding O Cualann member Aisling Lynch breaking ground at the group’s new development of co-operative housing in Ballymun, Dublin

Longstanding O Cualann member Aisling Lynch breaking ground at the group’s new development of co-operative housing in Ballymun, Dublin

Founded in 2014 by Hugh Brennan and Bill Black, Ó Cualann intends to create what it calls fully-integrated, co-operative, affordable, sustainable communities – and unlike many plans, Ó Cualann’s work is not purely theoretical.

Brennan explains that Ó Cualann has already developed housing in Poppintree, Ballymun, in association with Dublin City Council. The development, which consists of a mix of two-, three- and four-bed terraces in three phases, was able to go ahead because of the council’s commitment to lowering the cost of land – the single greatest cost problem in housing in Ireland today.

“We worked with the support of Dublin City Council. Dublin City Council has a lot of land in areas where there is more social than owner occupiers and they’re trying to re-adjust that balance,” he said.

“Our vision is for 60–70 per cent owner occupied, and among the remaining 30–40 per cent, which are rented, a third would be private affordable, a third social rental and third elderly or disabled. [Though] That’s not set in stone, its fluid,” said Brennan.

Getting this mix right is key, says Brennan, because ownership is an important factor in developing communities, but so-called “affordable housing” is itself unaffordable.

Average prices in Poppintree were between €170,000 and €177,000, whereas the likely market price would have been over €260,000.

“They’re located 7.5 kilometres from the city centre, you can cycle in; they’re near schools and Dublin City University; there are buses, there will be the metro, you’re minutes from the M50 and the airport – and there are 2,000 plots available in Ballymun,” he said.

Finished homes at the development, which consists of a mix of two, three and four-bed terrace units, built in three phases

Finished homes at the development, which consists of a mix of two, three and four-bed terrace units, built in three phases

Brennan is clearly convinced the development has worked, but the question is can it be rolled-out on a larger scale.

Ó Cualann pays €1,000 per plot, plus VAT. The typical value of a plot is around €20,000, so it is clearly a model that can only work if councils, which own the land, are more concerned about solving the housing crisis in their midst than in making super-profits.

Brennan says, however, that this is increasingly the case, and that more and more local authorities are taking an interest in the model itself, particularly as a form of regeneration and because a ‘clawback clause’ means that profiteering via house-flipping can be eliminated.

“We’re talking to Fingal, [and] they’re supportive; likewise Limerick, and we’ve talked to Waterford. We hope it can be replicated and scaled; we hope that other people can take up the model, rather than just doing projects [with us]. That’s our objective.”

In the case of Ballymun, Brennan calculates that the development could introduce as much as €13m into the local economy annually.

“If all of those 2,000 sites [in Ballymun] were brought in the multiplier effect would be tremendous. That’s capitalism at work,” he said.

For Brennan the idea is a mixture of co-operation and capitalism: “I’ve a vested interest in this: I’ve four children, whom I want to be able to afford a house. Won’t we be better off if we create social capital rather than financial?” he said.

On a national level, primary legislation may be required, however, to lay the groundwork for large scale development on council land. Ossian Smyth, Green Party councillor for Dún Laoghaire, says local authorities are interested – and more than aware of the problem.

“There’s a county development plan. Every local authority has to do that and you plan out in that how many homes you have to build. Our plan is 31,000 houses for 70,000 people, from 2016 to 2022, based on the regional planning guidelines,” he said.

“We have to make sure that we’ve zoned enough land and have enough density, plus have enough schools and transport.”

Dún Laoghaire-Rathdown County Council itself plans to build 540 houses on its own land in Shanganagh, beside a planned private development of 1,000 houses.

“[Then environment and housing minister] Simon Coveney told us we could have any money we wanted, when he was running for Taoiseach. He said he wasn’t being asked for enough money. The signs are central government is gearing-up to fund more building,” he said. The problem of land banking remains, however.

“The political debates and ideological debates are kind of over because everyone has realised the private developers are holding back. Land hoarding is going on, so our only option is land we already own and compulsory purchase.”

“All sides want to do something about it from a human point of view,” he said.

A VERY BRITISH HOUSING CRISIS

In September 2017, a letter published in a British newspaper became an unexpected internet meme, passed around because of its shocking content.

The letter, written by one John Searle of Grantham, noted that when he earned £1,000 a year working as a fireman he bought a house valued at £3,500. Today, that same “very ordinary” house is now valued at £650,000 and a mortgage for it would require a deposit of £50,000 and a household income of £200,000.

This alarming anecdote is backed-up by the cold hard numbers: £650,000 may not be the average, but the typical figure is no less unaffordable.

Official British government statistics indicate the average house price in the UK was £223,257 in August 2017. This figure, of course, downplays regional variations.

In England, an annual price increase of 5.2 per cent has taken the average property value to £240,325. Monthly house prices have risen by 0.8 per cent since May 2017.

In London, meanwhile, an annual price increase of 2.9 per cent took the average property value to £481,556.

Overall, income share spent on housing has trebled in the last fifty years, and housing in or near the centre of the capital is now so expensive that developers have resorted to building tiny “micro homes” in order to meet demand from young professionals.

Meanwhile, a September 2017 report published by the think tank Development Economics said London risks becoming a “ghost town”. Speaking about the report, which advocated smaller dwellings, the think tank’s Stephen Lucas said: “With greater numbers of people than ever choosing location over space when deciding where to live, building sufficient quantities of high-quality, centrally located housing will be essential for London’s future economic, social and cultural growth.”

It should be noted, however, that Britain is already home to the smallest dwellings in Europe, with an average floor space of 76 square metres. The Irish average is 87.7, while Germany averages 109.2, France 112.8 and Denmark 137.

Even the government has declared Britain’s housing market “broken”. Speaking to parliament, communities and local government secretary Sajid Javid, noted average house prices had jumped to 7.5 times average incomes and rents in many places swallowed more than half of takehome pay.

Describing the prospect of home ownership as a “distant dream” for young families, Javid said: “We have to build more, of the right homes in the right places, and we have to start right now.”

Dr James Heartfield, author of the book “Let’s Build!: Why We Need Five Million New Homes in the Next 10 Years”, says that prices are driven by the coincidence of both a shortage of units and the amount of credit in the market in previous years.

Heartfield says that as a result of these two phenomena the economics of the UK’s property market have taken on a somewhat fantastical dimension.

“It’s kind of deceptive,” he said. “Lots of people have properties that are worth vast amounts, but then they also have massive mortgages on these properties. So, while people do have a lot of capital, you can’t ever realise this capital. It’s such an overinflated market.”

Heartfield wrote “Let’s Build” in 2006, and in the decade that followed five million homes were not built. Despite hitting a seven year high in 2015–6, average figures peaked at just 164,000 per annum. Since then, there has also been the 2008 financial crisis, which only worsened things: in 2012– 13 the county hit a post-war low, building just 135,500 homes.

The pre-recession peak was 200,000 per annum. Only twice has UK housebuilding reached 350,000: once in the mid-1930s, and again in the late 1960s.

According to Heartfield, both the left and right recognise the problem, but, as yet, have not developed anything like a detailed plan to deal with it.

“I think it’s a real disaster in terms of political will. I’ve met Jeremy Corbyn – and pressed my book into his hand – and talked to him about the problem; we’ve [also] seen commentators like Owen Jones and Polly Toynbee who want to reverse Labour’s historic objection to new builds,” he said.

Of course, Labour and the Tories naturally favour different solutions. A further stumbling block is the current Conservative government’s weak mandate, and the fact that Brexit is taking up much of the country’s politics.

“Their belief that you could fix it by council house building is interesting, but we’d need to see more detail,” said Heartfield.

“On the Tory side, formally they’re committed to doing more as well, but at the moment they’re snarled up in the hiatus of Brexit – and they’re badly behind in the polls. In both parties the front benches are formally committed to building more homes, but it’s unlikely that we’ll see it happen,” he said.

For Heartfield, the real tragedy is that nothing that has happened was unexpected. “This was all utterly predictable. I can say that because we did, not just me, but also [his colleague, architect] Ian Abley, as well as [Bank of England economist] Kate Barker, who was shot down in flames for saying this,” he said.

Of course, despite being the area of highest pressure, the south east of England is not alone.

A recent report published by Shelter Scotland found that between April 2016 and March 2017 more than 21,000 individuals in Scotland made use of Shelter’s services – and not just those traditionally viewed as homeless.

The three most common problems were “struggling to pay or afford housing costs” (15 per cent), “housing conditions” (12 per cent), and “landlord issues” (10 per cent), while affordability was the main issue for private renters, social renters and homeowners alike.

Innovative ideas

Clearly, a new policy approach will be required, but in the meantime some innovative ideas are on offer.

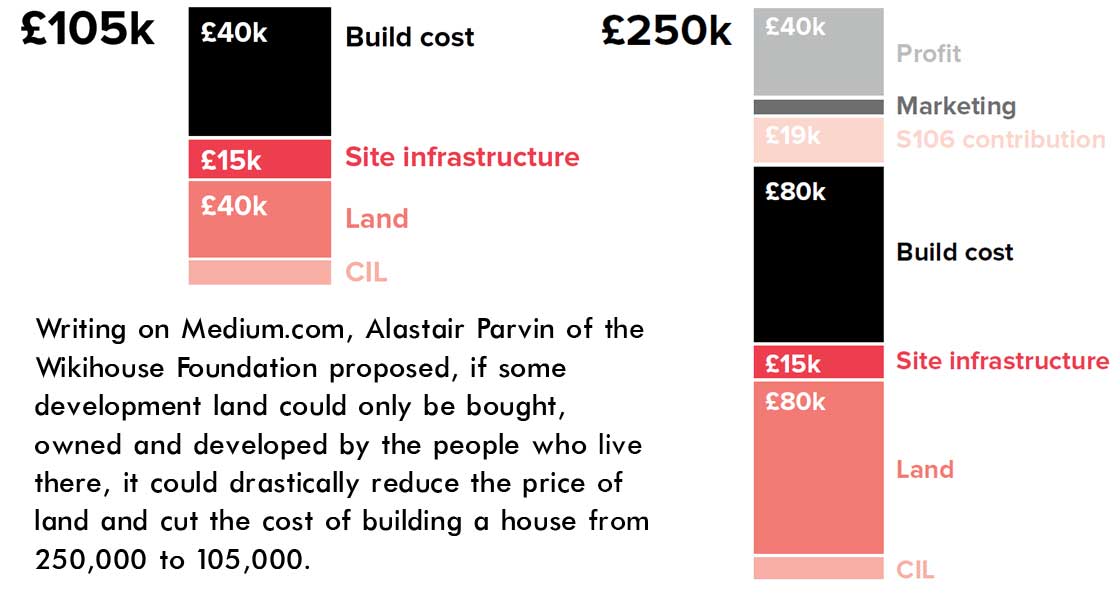

Writing on medium.com, Alastair Parvin of the WikiHouse Foundation has proposed what he calls “housing without debt”, which is effectively a call for the creation of a parallel market in land intended to reduce capital expenditure in housing development.

Working on the basis that land zoned for development is worth many times what agricultural land sells for, Parvin proposes that some land could be zoned so that it can only be bought, owned and developed by the people who live there. This would not only allow for cheaper development, but do nothing to stop the buying and selling of homes, so long as those homes were owner-occupied.

Parvin calculates that this could reduce the cost of building a house from £250,000 to £105,000, and, he says, the legal mechanisms already exist to allow for it in the form of the Self & Custom Building Act, the existence of Community Land Trusts and the simple matter of legislative provision for dwellings procured and owned by their occupants.

Like the Ó Cualann schemes in Ireland, it is unlikely to solve the housing shortage on its own, but then again, it isn’t intended to. What it could do, however, is dramatically lower the cost of entry to the housing market, particularly when twinned with peer-to-peer and mutualised financing. Bear in mind that building societies were initially developed to do just that – to build – and that ‘permanent’ building societies were a later development.

In the meantime, as pressure continues to increase on the housing market, any solution other than overcrowding is a welcome development

This article was originally published in issue 23 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge