- Upgrade

- Posted

How to save social housing blocks

Britain and Ireland’s post-war social housing blocks are seen as ugly and uncomfortable, and suffer from high energy bills, damp and mould. But three ambitious renovation projects show the answer doesn’t always lie in demolition.

Britain’s post-war house-building boom was all about numbers. The government piled ‘em high by funding first tower blocks, then mid- and low-rise blocks. Pre-cast solid concrete was the defining material, system building the defining method.

While indoor bathrooms and central heating were greatly appreciated by new occupants, the post-war dream of urban renewal quickly turned sour for many. Cold bridges and leaks led to condensation and mould, while outside there was sometimes social decline too. Many of these developments have now had a bad reputation for decades. Some have been demolished; others refurbished, but many are still crying out for improvement.

Parkview prior to retrofit

The three retrofit projects presented at a passive house conference, organised by Encraft earlier this summer in Birmingham, exemplify the challenge. Parkview Hub in Thamesmead, Erneley Close in Manchester, and Wilmcote House in Portsmouth are all run-down postwar housing blocks. The first two (where work is already well advanced) are single blocks of four and five stories respectively. Wilmcote House in Portsmouth (where work has just begun) is a lot larger, with 107 dwellings in three linked 11-storey blocks.

Parkview close to completion

All needed extensive repairs due to deteriorating fabric and leaks, and because living conditions were poor and energy bills high. All are now being retrofitted with the aim of achieving Enerphit, the Passive House Institute’s retrofit standard.

Erneley Close has both horizontal walkways and vertical piers or “fins”: the building is practically made of thermal bridges. Inside, the flats suffered from condensation and black mould. According to passive house designer Eric Parks, they were “amazingly cold and uncomfortable; they managed to be both stuffy and draughty”.

The Parkview Hub is owned by Gallions Housing; built from concrete panels, with lots of cold bridges, the windows and doors had already been replaced once but were leaking again. The mastic between the blocks was shrunken and leaking. Heating bills were as high as £40 per week.

Wilmcote House, belonging to Portsmouth City Council, was built from the Bison Reema system of prefabricated concrete panels. The average SAP rating was 55 and flats cost around £25 a week to heat. The storage heaters were hard to control, and the majority of occupants have been living at below recommended temperatures. Leakage and condensation both posed problems, and the flats suffered from damp and mould. Many residents have complained of poor health which some suspect is caused or exacerbated by their living conditions. A vocal residents group has demanded the landlord improves these properties.

The options open to the three landlords were to either demolish and rebuild, carry out a shallow retrofit, or go much further and undertake a deep retrofit.

Why not demolish?

Sometimes demolition is the only option, such as when a block is unsafe or otherwise irretrievable, or has acquired such a bad reputation that no-one wants to live there. Even retrofitted, housing blocks may remain unappealing to live in, but if knocked down, they could be replaced with new code four (Code for Sustainable Homes level four) or passive housing. It might also be possible to rebuild low rise blocks at a higher density. And at least you know where you stand with a hole in the ground. With a retrofit, you don’t know what you’ll find once you start work.

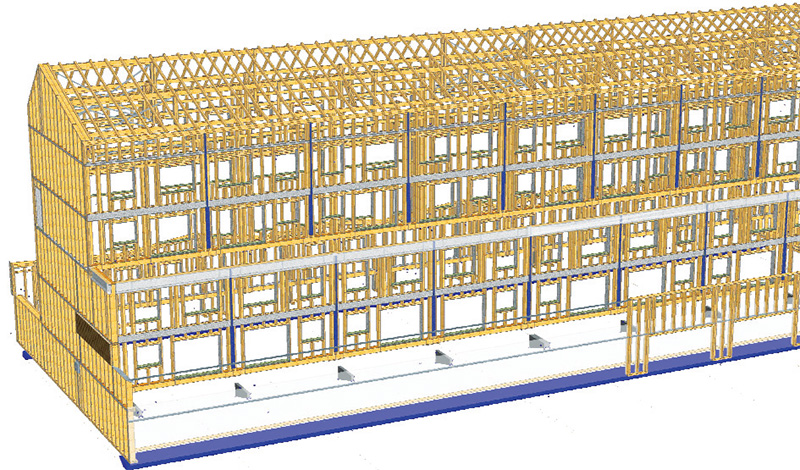

An illustration of the building’s retrofitted external timber frame

However, it is impossible to knock down and rebuild someone's home without causing major disruption to their life – and their community. There is also lost rent for the landlord when demolishing, and the expense of rehousing tenants.

Furthermore, demolition of social housing often leads to replacement by a mixed development in which the number of social rented units is diminished, meaning some social tenants cannot move back in, and the new units for sale may cost a lot more than prices paid to any displaced leaseholders – a trend criticised as ‘social cleansing’. If the landlord opts for retrofit, planning permission is likely to be much less of an issue. In fact, planners may well welcome the transformation.

Refurbishment also generally gives rise to much fewer carbon emissions than demolition and rebuilding – and when renovation is to the Enerphit standard, there is little danger of these emissions savings being outweighed by in-use energy consumption in the property.

The Gumpp and Maier wall panels arrive on site complete with windows and doors, vent penetrations, insulation, airtight layer; and cladding

But why go so deep?

The three reasons given most often by social landlords for aiming for Enerphit are: tackling fuel poverty, protecting their estate (and reducing maintenance), and the desire for quality assurance. Carbon reduction is not often mentioned. This may well be because fuel poverty is more pressing — however, it is also the case that actual carbon reductions from retrofit are hard to predict when people are currently under-heating their homes.

Social landlords want to tackle fuel poverty for the welfare of their tenants, but also because low-income tenants living in cold dwellings and struggling with bills are more likely to suffer damp and mould — which damages the property and leads to call-outs, maintenance costs and even lawsuits — and to have less money left over for rent.

Many landlords are concluding that standard low energy retrofits don’t really protect residents from fuel poverty, while new homes built to or above code level four are relatively warm and affordable to heat. Enerphit squares that circle, and offers a chance to match and even exceed code four level of performance.

Wilmcote House’s façade

The retrofit of Parkview in Thamesmead is pioneering the use of off-site construction to deliver accurate high-performance construction, minimising time and mess on site. Insulated facade panels complete with factory-installed windows and pre-fixed cladding came to the site and were bolted to the outside in a matter of days. Modelling indicates the retrofit should deliver an 85-90% cut in heat demand.

At Wilmcote House, according to the project architects ECD, achievement of Enerphit will cut heating and hot water costs by 90%, saving around £750 per dwelling each year. Comprehensive retrofit does a lot more than simply tackle energy bills, though. At Wilmcote, the plan is to wrap the entire building in external wall insulation and glazing to cut thermal bridging. Glazing the balconies and walkways should also make them safer, something residents had requested, and will also give each flat a sun room that can be used to dry clothes. (A similar strategy at Parkview has also created extra internal space.)

Steve Groves of Portsmouth City Council said a major motivation for Enerphit was to save on future costs. Having logged maintenance call-outs and expenditure for many years, the council will be in a good position to compare before and after scenarios, even for individual items such as window repairs (previously 80% of Wilmcote House residents requested window repairs over just two years) or redecoration for condensation.

Wilmcote House’s walkway

The council also hopes that by achieving Enerphit, the upgraded homes will perform well enough to ease the relationships between landlord and tenant, and between tenants, their homes, and their wellbeing: “There is an issue where tenants don’t want to use central heating and extract fans because of the expense. If their homes are upgraded to give a really good standard of performance, we believe this will reduce the desire of tenants to switch off these important services,” Groves said.

Practical challenges

Of course Enerphit means installing MVHR, and this is never straightforward for a retrofit. However it isn’t insurmountable. At Parkview Hub it was possible to take advantage of disused air heating risers to accommodate ductwork, and the fan units are being located in new space created by the retrofit. At Erneley Close the fan unit is in the bathrooms, and the ducting mainly runs though the existing services zone, plus some boxing in.

You might think that externally insulating rectilinear concrete blocks of repeating units would be relatively straightforward — but of course it isn’t. For one thing, these blocks are almost never a simple shape, thanks to the walkways and balconies. Uninsulated, these structures have a disastrous effect on thermal performance. Erneley Close superficially has a surface-tofloor- area ratio of around two – until you take into account the walkways and structural piers, which drive it up to around three.

Here the team opted to wrap insulation all over the top and bottom of walkways and fins – which involved fixing new handrails and incorporating a drainage channel without penetrating the insulation.

Erneley Close prior to upgrade work commencing

Even insulated, the walkways and piers still exhibit heat loss: “We are now at stage where the fabric is really high-performance, and perhaps one third of the losses are down to thermal bridges — there’s just so much total length that they still make a big impact, “ Eric Parks explained. At Parkview and Wilmcote the designers opted to glaze in the walkways. While this solves some problems, it may cause others. At Wilmcote the kitchen windows open on to the walkways. Most of us use purge ventilation via a window when we burn the toast, but after the walkways are glazed in, the windows will no longer be openable, because they face a fire escape route. Project advisors Encraft are now considering whether to install dedicated extract fans for more ventilation.

To investigate this they are taking advantage of a vacant dwelling where solutions can be tested. This empty unit is being retrofitted, complete with a working kitchen in which test meals will be cooked, to refine the ventilation design.

Resident disruption

The chances are most current occupants of blocks undergoing deep retrofit will be keen for their homes to be improved. However they may not be prepared for the reality of the intrusive works required. Retrofit with occupants in situ is usually hardest for people on night shifts, and those who are elderly, unwell or housebound, or have young children. Noise and dust are generally the main concerns.

It’s a lot easier for people to cope if they understand what will happen during the retrofit, and why. One resident at ECD’s previous deep retrofit in West London, who understood the retrofit would tackle her appalling draft problem, was philosophical: The noise was “hell” she said, “but even if you renovated Buckingham Palace you’d still have the noise. There’s no such thing as a rubber drill.”

The report on these residents’ experiences made the following recommendations: better advance preparation before the works begin, perhaps offering the most vulnerable the opportunity to move; better communication of the nature of the project and its energy saving potential; and making staff available to listen to residents’ concerns.

Experience on the more advanced of the Enerphit retrofits backs this up. At Parkview Hub, Martin Montgomery of contractor Gumpp and Maier says, things that might seem small caused great concern to occupants, but once the landlord met the residents, solutions could be found.

The careful application of external insulation begins

“The biggest single issue was probably the fact that to fit the cladding, all the TV dishes had to be removed, and people were really worried about this. However it was not that expensive simply to replace them with a communal TV subscription. Similarly, people were very concerned about their decor being damaged: yet they were happy to accept DIY vouchers, enabling everyone to take care of their own repairs.”

At Wilmcote, where work is just beginning, the team report that at the last consultation residents were 98% supportive of the scheme, with 78% of residents attending the session. With the opportunity to refine the approach by practicing in the vacant units, the idea is for the operation to be as slick as possible once they move on to occupied units: “The contractor has been allowed just six weeks access per flat,” says Encraft’s Helen Brown.

Sadly the best intentions to work with residents in situ can come unstuck. At Erneley Close the construction team found that, despite investigations at the start, many of the wall panels to which they intended to fix external insulation were in such poor condition that they had to be replaced with insulated timber panels instead – plus, the heating systems had to be removed, so the occupants did have to move out for a while.

Will it be worth it?

A new build to level four of the Code for Sustainable Homes could cost around £1,000 to £1,500 per square metre. New-build passive house dwellings may cost a little more – recent analysis has suggested prices of £1,400 to £1,600.

High performance insulation fitted at door thresholds to minimise cold bridging

If the landlord has a choice between rebuilding and retrofit, this can leave quite a generous budget for retrofit – especially if the refurbishment can be completed without moving the occupants out and losing rent. While the Parkview Hub retrofit is now quoted as costing £1,114 per square metre (a figure that includes some newly built accommodation too) it has to be remembered that achieving code four has been honed in price over a number of years, while Enerphit is still very new.

The Wilmcote House retrofit is going ahead on the basis that it would be cheaper than rebuilding the same number of units to code four and paying the associated costs such as lost rent. At Erneley Close, according to developer R-Gen, the costs of the Enerphit aspects of the work are estimated at around £1,000 per square metre.

But given that Enerphit is so demanding, does it make sense to go this deep? Some eyebrows have been raised at the cost. One point often made is that the payback time in terms of energy savings is much longer for a full Enerphit than for selected interventions such as roof insulation.

However, as Dr Diana Ürge-Vorsatz, director of the Center for Climate Change and Sustainable Energy Policies at Central European University, argued at the 2014 International Passive House Conference, a shallow retrofit today locks out the possibility of a deeper retrofit for years, even decades, to come. This is catastrophic for tackling climate change. And if you're going to the trouble of designing a refurbishment, securing finance, and making the occupants' life a misery, why wouldn't you do as thorough a job as you can, now?

Insulated timber panels were used to cover much of the building’s façade

“Going to Enerphit will incur extra costs above simply upgrading to the current building regulations, but it should future-proof our stock,” explained Steve Groves of Portsmouth City Council. “A refurbishment like this is expected to last 30 years, and over that 30 years it will have to cope with changes in government standards and targets – who knows what the next 30 years will bring?

“We are hoping that by doing as much as we can now, we will be one step ahead and won’t be in a position where requirements change but we can’t react across the whole lot of our stock quickly enough.”

David Williams, deputy chief executive of Erneley Close’s owners, Eastland Homes, admits that upgrading to Enerphit is expensive. However he says it makes sense from a social and financial point of view: “The residents in the maisonettes are the poorest people in our housing stock, and we would have had to have done considerable work to get the homes up to Decent Homes standard anyway.” His team partner Phil Summers, director at R-Gen, agrees: “The world has moved on since Decent Homes was the standard to aspire to.”

Project credits

Erneley Close

Client: Eastland Housing

Architect: 2e Architects

Developer: R-Gen

Contractor: Casey

Passive house designer: Eric Parks

Parkview Hub

Client: Gallions Housing (part of Peabody Group)

Architect: Sustainable By Design

Contractor: Gumpp & Maier

Passive house consultants: Chiel Boonstra of Trecodome

Feasibility study: ECD Architects

Wilmcote House

Client: Portsmouth City Council

Architect: ECD Architects

Contractor: Keepmoat

Lead designer for contractor: Sustainable by Design

Passive house consultants: ECD (client), Encraft (contractor)

Retrofit and health – some joined-up action at last?

The benefits of retrofit go beyond energy bills, and indeed, beyond those who occupy and own the buildings. A recent UK Green Building Council report notes that the calculated annual cost to the NHS in England of cold homes is £1.36 billion, as well as the associated social care costs. They estimate that, for example, insulation of all solid walls in the UK would give health improvements equivalent to £3.5bn to £5bn over the lifetime of the measures.

Some health authorities are already investing in improvements to the housing of their more vulnerable patients, for example by funding new boilers and insulation in patients’ homes, in a bid to improve people’s health and quality of life, cut treatment costs and reduce expensive hospital admissions. The UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence is currently developing advice to clinical commissioning groups on reducing excess winter deaths and illnesses – including advice on promoting retrofit.

Though the wider social benefits are harder to quantify than simple energy payback calculations, they are just as important, and are taken very seriously. Three universities,

plus the BRE and the Europe-wide Europhit programme, are studying how the Wilmcote House retrofit affects the lives of residents, looking not just at energy and comfort,

but also health and wellbeing. As well as the tenants, the research will involve neighbouring health centres and schools to get a rounded view of whether the whole process has been worthwhile. The results will be important reading. Wilmcote House is probably the most wide-ranging, but all three projects have formal research programmes.

Other social landlords – and indeed local authorities and even health bodies — will be looking closely at the results. It will be on much wider issues than just energy performance and build costs that the success of these Enerphit projects should be judged.