- Case Studies

- Posted

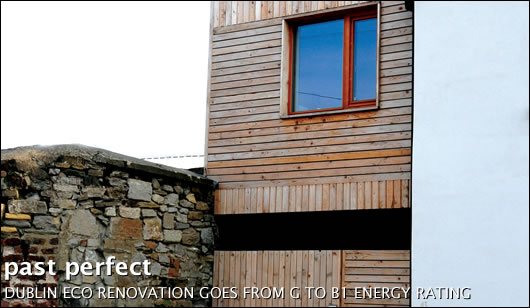

Past perfect

As the new-build sector grinds to a halt a window of opportunity has opened for builders, architects and other construction service providers – refurbishing Ireland’s existing housing stock. Jason Walsh visited an end-terrace house in inner city Dublin to see just how significant the improvements can be

It’s official: the building boom is over – the number of house completions in August dropped to just 3,605 while figures show that total completions in the first six months of the year stood at 27,736 units, 29 per cent below the same time in 2007. Construction employment, meanwhile, has bottomed-out and is now eighteen per cent lower than last year according to figures released by the Central Statistics Office. Everyone in the industry is asking: “What is to be done?”

One answer comes straight from the sustainable sector: improve the existing housing stock. The low quality of Ireland’s housing stock has been something of a hobby horse for Construct Ireland for some time now but it appears that the conditions may finally be right for a significant programme.

Of course, not everyone is waiting for the government and the construction industry to get into gear. Plenty of home-owners are taking matters into their own hands and re-working typically energy inefficient houses around the country. Catherine Cleary and her family did just that, buying an unremarkable end-terrace in inner south Dublin and transforming it into a green house that wears its sustainability on its sleeve.

The house is likely to be familiar to many Construct Ireland readers – Cleary, a journalist, documented the building process in the Sunday Business Post. Cleary notes that the house’s efficiency was somewhere around the G-standard of Building Energy Ratings (BER) and is now a high-B.

For Cleary and her family going green was an imperative: “We lived in a Victorian terrace house in Wicklow town before,” she said. “It had some modifications – double glazing and a modern heating system, but it was pretty energy hungry.”

As being environmentally conscious is something of a way of life for Cleary and her family, the initial decision was made to take the major step of going green at home, but cost considerations were a factor, as they always are, in just how much could be done.

The first thing she and her family decided to do was to move back to Dublin. Both she and her husband work in the city so they were able to identify commuting as a major source of energy inefficiency: “It seemed crazy to invest in a pellet boiler in Wicklow and commute 60 miles a day,” she said. “From knowing that we were going to do work on the house, we did it in the greenest way possible.”

So: a house in Dublin was called for. Leaving questions of embodied energy aside, it is of course easier to build a green house from scratch than it is to renovate an older house but it is also a costly and time-consuming process.

“We started from the ground up,” she said. “We knew it was going to be a challenge.”

Most of the financial outlay was at the beginning of the project and the green measures added an estimated e20,000 to the total cost of the renovation but Cleary is estimating a six per cent overall return on investment in terms of reduced energy consumption.

The house underwent significant refurbishment and extension, which increased the floor area from just over 80 square metres to 131.5 square metres, resulting in a house comprised of three bedrooms, a study and increased living, dining, kitchen, utility and bathroom spaces.

Two new extensions were added to increase space, one to the rear ground floor (above); and another two storey extension at the side of the house

Cleary engaged Melted Snow Architects, the practice of Jim Lawler, to design the new family home.

Lawler decided to add two new sections to the house, one an extension to the rear ground floor that doubles the size of the living space and a two storey extension at the side, which contains an external storage space and the stairs and landing areas. Therefore, aside from the striking timber aesthetic that plays the modern against the traditional, Lawler’s major contribution to the project was to completely redefine the internal space, using the two extensions to allow for the reconfiguration of the existing dwelling.

Now, virtually the entire ground floor is a single room, open-plan living and kitchen area with two ancillary areas – a small, discreet sitting room at the front and a utility room behind the kitchen. The rear wall, south-facing, is glazed with sliding doors.

“It just made sense to be open plan,” said Lawler, “the idea of a separate dining room, for example, is kind of outdated now. My main concern is creating the space in which the client can do their own thing. My job is done when there’s a blank canvas.”

The new-build sections of the house are stick-build timber frame. Lawler explains their configuration: “There are 200 by 75 structural studs with waterproofed OSB on the outside face, a breather membrane, battens and the cladding – a profiled cedar from Kilkenny.”

Like many of today’s architects, Lawler proposes that sustainability should be a central tenet of the practical side of architecture: “It shouldn’t be a separate issue for architects, it should inform the design and vice versa,” he said. “To separate the two doesn’t make sense to me as a designer – there is a responsibility on architects to be green.”

Rebuilding history

When Cleary bought the house, she and her husband knew that major work needed to be done. After all, this was a typical Irish end-terrace house with double glazing being the only significant upgrade that the building had ever enjoyed. As a result, the house was cold, leaky and had a high energy demand.

Solar vacuum tubes were installed on the cedar clad, stick-build timber frame extension to provide for hot water needs and they are orientated to maximise solar gain

Sustainability consultants BESRaC were brought in after planning in order to beef-up the house’s green credentials: “The original house was a basic, solid masonry construction with minimal insulation,” said BESRaC’s Patrick Daly. “I made a basic report on building methods and then a more detailed report on the building fabric and the energy efficiency specifically.”

Daly’s recommendations were then brought into the building process: “We didn’t test for air-tightness before the build because the house was about as air-tight as a sieve,” said Cleary.

“Patrick Daly advised the builder on how to seal and tape everything. Effectively it was a very manual process, we had to ensure the windows were sealed and installed properly – it was very labour intensive extra work to ensure that there were no gaps created by the services.”

Daly performed two air-tightness tests on the building. On the first test the building achieved 9m3/hr/m2 at 50 pascals pressure, a figure that is marginally better than the minimum air-tightness requirement for new homes under the recently introduced changes to Part L of the building regulations. The second test, carried out after further work on air-tightness, yielded an improved air permeability result of 7m3/hr/m2.

Such a figure must be judged in the context of the difficulties involved in retrofitting air-tightness. This figure is roughly 30 per cent better than the 2008 Part-L regulation for new builds but falls well short of the passive house standard, something that has an effect on the cost-effectiveness of the house’s heat recovery ventilation (HRV) system.

Galway-based heat recovery specialist ProAir Systems supplied an Irish-manufactured ProAir 300 heat-recovery ventilation system. The company’s David McHugh explained that with ventilation systems it is essential to match the demand to the system: “It’s very important to specify properly,” he said. “It’s not a case of one-size-fits-all.”

|

| A glass balus trade helps to make the most of daylight in the extension |

McHugh explains that ProAir was determined to remove any possible noise issues and to accurately match the demand for fresh air to the volume supplied: “A bigger system would be totally unsuitable – you don’t need half an air change per hour by mechanical means,” he said.

However, the house’s air-tightness performance does have an impact on the cost-effectiveness of HRV: “Below 5m3/hr/m2 at 50Pa it becomes more essential, but I’ve had heat recovery ventilation at home [in a leakier house] for twelve years and I wouldn’t be without it.”

As the project included significant renovation and building work there was a major opportunity to make improvements in the building fabric. The new build sections of the house are insulated with 200 millimetres of rock wool (increased from the planned 150 millimetres) and the new floor areas are insulated with 120 millimetres of Kingspan insulation and 70 millimetres on the roof. 150 millimetres of rock wool is used between the joists in the roof, topped with plywood and 100 millimetres of Kingspan insulation.

The u-values for the new walls come in at 0.18 W/m2 K, while the new roof and new floor areas achieve u-values of 0.12 W/m2 and 0.16 W/m2 K respectively.

As Daly notes in his report: “These advanced u-values traded off against the ‘improved’ u-values in the existing fabric with averages still in excess of current building regulations.”

Improvements were also made to the thermal performance of existing building. Firstly, the building design allowed many of the old external wall areas to become internal walls which could be better built.

The natural light-flooded kitchen area, complete with bamboo worktops and salvaged timber flooring

Secondly, further insulation was specified that was compatible with the existing structure, notably, 70 millimetres of external insulation from Kingspan added to the front of the dwelling.

Daly explained that this was in part a spatial issue as the alternative, dry lining, would have reduced the useable floorspace, but also that external insulation is better at reducing thermal bridging: “You’re going above the [upper] floors and down into the ground, so there are no gaps in the insulation,” he said.

Building work, handled by McGlynn Construction, started in October 2007 and was complete by April 2008.

“It was a sizeable enough job,” said Denis McGlynn, “a medium-to-big renovation in relation to Dublin.

“Aside from the two storey extension to the side, we removed the back wall and created an open plan space downstairs. We’re very happy with how it worked out. The timber construction of the walls was new to us – most timber-frame houses still have a block-work leaf.

“The main emphasis was very much on insulation. After that the building was sealed with a Pro Clima membrane and tape on the inside. It was then battened on the inside – the services run through that cavity, which was filled with 60 millimetres of rock wool,” said McGlynn.

Fireplaces were also sealed in order to prevent heat loss.

Triple glazed N-Tech windows from NorDan, supplied by the Dublin Door Store, replaced the existing double glazed units to the front. High performance double glazed units were used to the rear on the ground floor where the entire wall is glazed.

Nordan’s John McMenamy told Construct Ireland: “N-Tech is a range of windows. There are two types, low-energy and passive standard. This house used the passive standard windows.”

N-Tech passive standard windows have a u-value of 0.7 W/m2 K for the entire unit and are triple glazed and argon-filled. Nordan tend not to use Krypton because although it achieves a lower u-value, it is high in embodied energy.

The triple glazing is a major factor in lowering the u-value: “1.6 would be a good u-value on a typical Irish window,” said McMenamy. “The lowest we can go with double glazing is 1.2. We do that with a thermal break in the frame.”

The windows in Catherine Cleary’s house are made from PEFC-certified Nordic pine: “We have a full chain of custody,” said McMenamy. They achieve an A-rating from the British Fenestration Rating Council.

Hot stuff

The house’s primary space heating system is a condensing gas boiler. Cleary considered other options such as a ground-source heat pump and biomass but found the capital costs of the former too high and access a problem for the latter, so she made the decision to put the money into lowering the heating demand by increasing insulation.

Nevertheless, Patrick Daly points out that the gas system achieves 92 per cent efficiency, adding, “the insulation standards should mean the boiler is being called on very little.”

Daly’s assertion is backed-up by Cleary’s experiences so far: “We could have put in the Rolls Royce of heating systems but if the house wasn’t insulated properly it wouldn’t make sense. We’ve [only] used about six hours of heat since we moved in,” she said.

The gas boiler is joined by solar water heating in the form of 40 vacuum tubes, with an expected output of 1,600 kilowatt hours per annum.

Salvaged materials includes doors, bath and toilet

Stephen Bray of Alternative Energy Ireland, who supplied the solar system notes that access was the most difficult issue: “It was an awkward install but because it was a flat roof we were able to orient the panels six degrees west of south – it’s perfect orientation.

“It’s just doing water,” said Bray. “60 to 65 per cent of the house’s hot water need should be covered – 100 per cent of need in the summer, tapering down to forty per cent in the winter.”

The solar system stores hot water in a 250 litre tank and uses stainless steel piping, cylinder and frame: “It’s better for longevity,” said Bray, “you won’t get corrosion and leaking in the piping.”

Bray estimates an eight year pay-back on the capital investment of installing the system.

Flowing back

Aside from reducing energy need and improving the efficiency of the heating systems, Cleary made the decision to go a few steps further in the quest for sustainability.

A rainwater harvesting system was purchased from Molloy Precast. The company’s Michael Cahill explains: “It’s a 3,500 litre storage system. Most people in Dublin [who use rain water harvesting] use it for the toilets but it can also be used for all [non-potable] cold water in the house.”

“We use it for the toilet cisterns and washing machine,” said Cleary, who has found that the tank provides four to five days worth of water: “A four day dry spell means it goes over to the mains again.”

Cahill explained to Construct Ireland: “There is a 750 millimetre vertical pump that seeps it at a steady pressure of 30psi, or two and half bars in metric terms. If it’s dry, on the rare, rare occasion [in Ireland] the flow switch brings in the mains water.”

In addition, as an extra touch, as many materials used on the house’s interior as possible are salvaged or recycled. Bamboo work tops were specified in the kitchen, salvaged timber flooring, originally from a Dominican sports hall, and the sink and bath in the bathroom were salvaged – an approach also applied to the existing resources within the house. “The old doors were much nicer than anything we could get new, so we stripped them and kept them”, said Cleary. A-rated appliances were chosen in the kitchen, and cold cathode spotlighting has been used as an alternative to CFLs throughout.

The fabric, heating and lighting improvement measures have had a significant impact on the energy efficiency and notional Building Energy Rating (BER) of the house – the house cannot have an official rating, given that BERs are not available for existing dwellings until January 2009. The notional BER marginally exceeds the newest 2007 Part-L building regulations, rating at the upper end of the B1 band at approximately 80-85 kilowatt hours per metre squared, per annum – close to an A3 rating. In fact, the addition of on-site micro-generation of renewable energy would easily lift the house to an A-rating.

The question is: was it worth it? In practical terms, yes. Clearly has a larger, more comfortable and energy efficient home that costs less to run – a recent electricity bill, for example, came in at just e33 for two months. Cleary herself estimated in her column in the Sunday Business Post that the house is at least 40 per cent more efficient than most of the 500,000 new houses and apartments built in Ireland in the last decade. She also made a rough calculation that, “this house will use around e900 of gas and electricity every year, a saving of some e800 annually on typical heating and running costs.”

Virtually the entire south-facing rear wall on the ground floor is made up of double double-glazed units

In investment terms, it’s harder to say. Cleary has no intention of moving and it is currently difficult to discern if people will pay a premium for a house with a good BER in today’s volatile market: “When the energy ratings come in from January next year we’ll find out,” she said.

“Right now it’s hard to know if people will be willing to pay more for an energy efficient house – people are more likely to be wowed by a granite work-top. People are coming round to [energy efficiency] but it’s still seen as a bit of a woolly jumper thing.”

A woolly jumper thing it may be, but when the winter chill settles in Cleary and her family are unlikely to have to ‘put on another jumper’ as the old dictum goes.

Selected project details

Architect: Melted Snow Architects

Main contractor: McGlynn Construction

Sustainability consultant: BESRaC

Triple-glazed windows and doors: NorDan , via the Dublin Door Store

Heat recovery ventilation: ProAir

Solar Panels: Alternative Energy Ireland

Air-tightness system: Pro Clima from Ecological Building Systems

Floor, roof and external insulation: Kingspan

Rainwater harvesting: Molloy Precast

Kitchen and appliances: Delgrey Kitchens

- Articles

- Case Studies

- Past perfect

- Housing Stock

- Propery Boom

- Market

- Collapse

- sustainable

- renewable

- Condensing Boiler

Related items

-

A grid of their own

A grid of their own -

It's a lovely house to live in now

It's a lovely house to live in now -

Housing for who?

Housing for who? -

Are lower land values the silver lining of the crisis?

Are lower land values the silver lining of the crisis? -

Stirling Work - The passive social housing scheme that won British architecture’s top award

Stirling Work - The passive social housing scheme that won British architecture’s top award -

Woodland wonder

Woodland wonder -

Westmeath NZEB scheme opens its doors

Westmeath NZEB scheme opens its doors -

A housing boom without the houses?

A housing boom without the houses? -

Two houses for the price of one

Two houses for the price of one -

Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink

Water, water, everywhere, nor any drop to drink -

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay -

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather