- Case Studies

- Posted

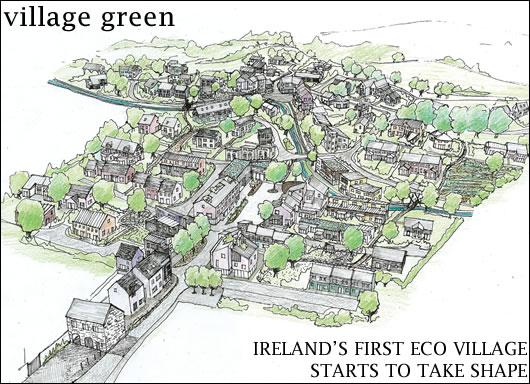

Village green

Plans for the first Irish eco-village have been in the works since 1999, but – finally – work is well underway at The Village in Cloughjordan, Co Tipperary. Following a site visit in December, Lenny Antonelli gives an overview of the innovative project’s renewable energy district heating system and sustainable planning and community design approach, before profiling four of the first houses to be built.

If you're involved in sustainable building or green energy in Ireland, you'll have heard about The Village. The planned eco-village in Tipperary has been in the pipeline for ten years, but what was once a concept is quickly becoming reality: 25 houses are under construction and some are now finished.

And the variety of building methods on site is striking, from a host of timber frame systems to various forms of hemp-lime construction to durisol blockwork, a mix of cement and wood fibre. Construct Ireland will profile the most interesting projects as they're finished - to get started we're featuring four buildings in this issue. "What you will see here is very much a test ground for different types of builds," says Dave Flannery, the project's sales manager.

The Village's history began in 1999, when a group of environmentalists held a meeting in the Dublin's Central Hotel looking for people to plan Ireland's first eco-village. More than 40 sites were considered before Cloughjordan was chosen. The organisers set up a co-operative company to oversee the project – everyone who buys a site becomes a member.

A fairly typical Irish village, Cloughjordan had key things going for it: a train line to Limerick and Dublin for a start, and good quality farmland too. Building off a town and making use of existing services also seemed much greener than starting from scratch. "Most eco-villages are standalone, but this is integrated into an existing community," Flannery says. "That's probably the most exciting part of it."

Outline planning permission was granted – though with 32 conditions attached – and without objections. The members Construct Ireland spoke to put the lack of objections down to the thorough consultation process they went through with the local community. Brian O'Brien of Solearth Architects, who drew up the masterplan for the 67 acre site in collaboration with Sally Starbuck of Leech-Gaia Ecotecture and the village members, says hiring a professional design team of architects, engineers, hydrogeologists, archaeologists and others was key to convincing planners at the early stages.

Work is now underway on 25 houses at The Village

The masterplan divides the site into roughly three parts: a third for housing, a third for food production and a third for woodland. The farm and woodland areas are near the open countryside at the north and west of the site, leaving the bulk of buildings in the south off Cloughjordan main street. But a steep and narrow road separates the town and eco-village, so creating a natural transition between the two wasn't totally straightforward. "You'd usually try to make a two-sided street with buildings on both sides of the road but we didn't have enough width," O'Brien says. To make the connection as seemless as possible, Solearth designed a curved building that will include a cafe/bookshop and apartments to mark the corner where the old main street connects with the new eco-village. An old barn at the site's entrance has also been refurbished.

The residential zone includes 130 units across detached and semi-detached houses, terraces, apartment blocks and live-work units. Members can design a house from scratch or buy into a project with an existing design. Community spaces are the heart of The Village. A market square off Cloughjordan main steet will be the economic hub and feature live-work business units and two community buildings – one for educational and community use, the other for cultural activities. Work has also started on an 'eco-hostel' nearby. From the market square footpaths and a stream make their way to the site of the planned 'community crescent' – the northernmost community space – at the back of the residential quarter.

From the start the designers aimed to discourage car use, making roads narrower than in a typical estate to slow vehicles down, and forcing motorists to take a winding route through the site. Only pedestrians and cyclists can use the main entrance from Cloughjordan – motorists have to take a detour to get in – and footpaths in the eco-village are kept separate from the roads to prioritise pedestrians. "We wanted it to be the opposite of a housing estate," O'Brien says. "For many such developments the first thing in question is to decide where the traffic is going, but we wanted that to be the last thing to influence us."

(left) a local bicycle shop, one of a number of new green businesses that has opened in Cloughjordan since The Village project located there; (right) a renovated stone barn marks the entrance to the site off Cloughjordan main street

O'Brien knew it would be a challenge to create the same variety and complexity as in the existing town over just a few years. To aid this process, it was envisioned from the start that all the houses be designed by different architects. And when deciding where to put buildings and public spaces, the masterplan sought to balance the need to maximise solar gain (by building on the east-west axis) with the need to create a link to the existing town (by developing along the north-south axis).

Solearth recommended a maximum and minimum size for houses, but O'Brien is concerned many people are aiming for the max. He believes this could give the eco-village a denser feel than some expected, and says the easiest way to build green is to build smaller. But he also points out that even a 'normal' house and householder here will be quite green because of the project's inherent features – the renewable district heating, central wastewater treatment, allotments and reduced need for a car.

Every house built must adhere to the village's eco-charter. "It's a document that members have helped to craft, and it's a living document so it's changing all the time," Dave Flannery says. The charter says that buildings should be highly insulated, make use of passive solar gain and renewable energy, minimise potable water consumption, reduce construction waste and use low embodied energy materials.

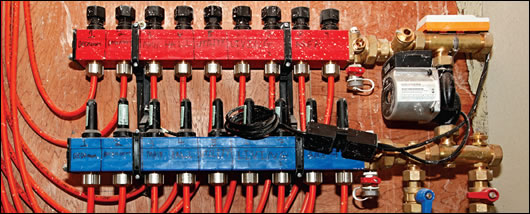

All buildings will be heated by the site's crowning engineering achievement – a 1MW wood-chip district heating system. Two 500kW boilers heat water that's stored in a 17,0000 litre buffer tank. "We specifically chose wood chip rather than wood pellet because it can be produced locally," Flannery says.

(clockwise from right) The energy centre which houses two 500kW wood chip boilers in the energy centre; wood chip is currently sourced from Ballinasloe, Co Galway and is stored adjacent to the boilers; pre-insulated Calpex and Casoflex pipework from Polytherm was installed on site

Cork-based Renewable Energy Management Services (Rems) supplied the boilers, buffer tank and most components for the system, which was co-funded by the European Commission's Concerto programme through Serve – the Sustainable Energy In a Rural Village Environment programme – in north Tipperary. Serve is also running a building energy upgrade scheme in north Tipperary, which was profiled in the November 2009 issue of Construct Ireland (Issue 10, Volume 4).

Designing the district heating system posed challenges, says Trevor Buttimer of Rems – for a start the system had to be installed before houses were finished. "Nobody can tell you exactly the square meterage of the houses and what the largest and smallest heat demand will be," he says.

Rems installed an 800 litre hot water buffer tank in each house – this allows residents to draw hot water from their own tank rather than directly from the network, helping to smooth peak loads. "That keeps the boiler capacity down and keeps down the temperature and pipe size you have to put in," Buttimer says. "If someone wants hot water, the buffer management system is monitoring the system and trying to replenish the buffers evenly and minimise peaks."

If there wasn't a buffer tank in each house residents would have to be able to draw hot water instantly from the district heating system – the network would need to be hot all the time and require a lot more capacity, Buttimer says. "Normally people see the storage of hot water as a negative thing but in this case well-insulated storage is being used to improve efficiency. The buffer tanks in each house have a tank-in-tank system in the top half which prepares domestic hot water, the remainder also acting as a buffer."

The system will deliver water around 60°C – this should encourage homeowners to install low temperature heat distribution systems, and will allow the whole network to be maintained at a lower temperature. Delivering water at 80°C would have been tough anyway with almost 4km of piping between the central buffer tank and the buildings. "There's no need in a modern well insulated house to be putting 70°C or 80°C water into radiators," Buttimer says.

Rems will also supply heating controls to each house. The controllers will monitor each building's energy use in detail, and Rems plan to collect and analyse the data. With such a large site, the efficiency of the pipes carrying heat from the energy centre to buildings was crucial. Rems opted for Calpex pre-insulated Pex piping, supplied and installed by heating specialists Polytherm, part of the Hevac group of companies which also includes renewable energy specialists Origen Energy. "Of all district heating pipework it's got the highest insulation value," says Polytherm's Seamus English. Calpex is insulated with pentane blown polyurethane, and the inner pipe, insulation and outer extruded jacket are bonded together in one homogeneous unit.

The two wood chip boilers will be supplemented by a 506 square metre array of industrial size flat plate solar thermal collectors – the largest in Ireland. The system is designed by Rems and will be supplied and installed by CareyGlass, and should produce between 480 and 500 kWh/m2/year. The rows of collectors will be kept 4.8m apart to prevent any over-shadowing, and the array should supply most of the eco-village's hot water demand in summer.

Cloughjordan is a fairly typical Irish village with a population of about 700

Polytherm supplied Casoflex pipework – a flexible pipe that can safely handle high temperatures (up to 150°C at a pressure of 25bar) – to take heat from the solar array to the main buffer tank.

The Village's drainage strategy is based on the principles of sustainable drainage systems – or Suds – which aims to copy natural systems to manage water run-off. Surface water finds its way slowly to the stream through a series of swales – shallow vegetated channels – and french drains. Retention beds hold water for hours or days in the event of a downpour, though in dry weather they simply serve as open spaces.

Originally a straight and steep drainage ditch, the stream was developed into a meandering water-course with a gentler slope. "If you bend the stream you get a lot more connection with the land, and the more overlap between the two habitats the richer it's going to be," says Solearth architect Brian O'Brien. "It's also much less steep than it was before – that allows birds and waders to get down and into the water." A boardwalk will be built along part of the stream too.

All mature trees on the original site were preserved, and one third of the land will be dedicated specifically to woodland and forest gardens. Members have already planted over 70 varieties of Irish apple trees in a nursery, and native species of tree will take priority in the woodland. Fruit and nut trees and other productive plants will be scattered around the whole site – the idea is to create an edible and biodiverse landscape, what Brian O'Brien calls an "inhabited habitat".

Members have leased a further 21 acres nearby and hired a farmer to produce a range of vegetables and fruit as well as eggs and milk. Non-members living locally can join the scheme too. "It's the first community supported agriculture scheme in Ireland," Dave Flannery says.

A temporary packaged wastewater treatment system treats wastewater on site, and members are weighing up their long-term options for wastewater treatment. The original masterplan included a design for a reed bed treatment system, but the possibility of developing an anaerobic digestor or other green technology to treat wastewater in the wider area is being explored. Brian O'Brien would like to see the original reed bed developed though. "It's probably the most professionally designed large scale reed bed system in the country," he says, "treating wastewater naturally would be last part of the eco-equation."

About 50 houses should be finished by the end next year. As buildings are completed surrounding areas will be landscaped, and the site will slowly be transformed from a building site into a living community. When it's finished the eco-village will add about 300 new residents to Cloughjordan's population of about 700. "The early adopters [members living in Cloughjordan] are really vibrant, they're great people and have a created a situation where there's no green - non green divide," Brian O'Brien says.

Though one shopkeeper Construct Ireland spoke to said just a few locals remained cynical about the eco-village, its effect on the town seems to be overwhelmingly positive. Davie Phillip of Cultivate (the Dublin-based centre for sustainable education) – and founding member of The Village – lists businesses that have been set up locally by eco-village members or others in the last few years: he mentions a bike shop, a cafe and bookshop, an energy assessors, a book binders, a bakery and a sustainable transport consultancy. "One of the things I'm most excited about is showing Cloughjordan as a model of rural regeneration," Phillip says.

He and his colleagues are moving part of Cultivate to Cloughjordan, while an education and research group is highly active in the eco-village and planning its own activities. Phillip wants The Village to become a green education hub, with a focus on practical, hands-on learning. "It will have more impact to demonstrate sustainability in a sustainable community," he says.

The project is finally coming to fruition, but getting here hasn't always been easy. Members purchased the land at the height of the property boom, and land prices have plummeted since, though construction costs have fallen too. "Now our biggest challenge is for people to get capital or sell houses to come into the project," Flannery says. He believes it's important those who can't afford to build have the opportunity to join, and says members are exploring how that chance could be offered through renting, affordable housing and social housing.

About two thirds of the sites have either been sold or have someone committed to buy them. More sales are needed to fund some community facilities, but members are exploring the possibility of a 'community build' and using The Village as a base for apprenticeships to lower building costs. But they're not lacking for community facilities in Cloughjordan, and Flannery is bullish about the future: "We're expecting that over the next year there will be a large take up on the remainder [of unsold sites]," he says.

The Village’s sales manager Dave Flannery has been a member for about four years

"We would consider a lot of the hard work already complete," Flannery adds. "As a pioneering project it hasn't always been easy. There's no template for what we're doing, so we've had to tease issues out and deal with problems as they've arisen. From a planning point of view, 130 houses going in with different people and different ideas - that was a challenge in itself."

On of those people is John Jopling, a 74 year old former lawyer from London, who's hemp-lime house is almost finished. "We had problems buying the land, we had problems raising the money to buy the land," he says, "we had problems raising the money to put in the infastructure." Members have also come and gone.

But Jopling believes a project like The Village is inherently resilient. "When you have a project like this that is people-run, that's organised and owned and belongs to the members in effect, it's got incredible resilience," he says. "A developer would have just walked away and cut his losses. But we have persevered."

Selected project details

Client: Sustainanle Projects Ireland Limited (The Village)

Masterplanning: Solearth Ecological Architecture & Sally Starbuck

District Heating System: Renewable Energy Management Services

Supply and installation of solar thermal array: CareyGlass

Cost consultants: Gardner and Theobold

Engineering: Buro Happold

Visit www.thevillage.ie for more information

The Kellys had always planned to build a low energy home, just not at The Village. “We wanted to build a house, we were looking for a site, and regardless of where, we were going to build a very modern energy efficient house," Anthony Kelly says.

The couple were motivated by green reasons and energy costs, but comfort was the big factor. “The first house we bought was a standard Irish construction, and it was poor,” he says. “It cost a lot for oil, and even after that it was draughty.”

The house’s simple cube shape is designed to reduce the surface area and minimise heat loss; an automatic floor sander smoothes the solid timber floors

They saw the eco-village mentioned on TV, decided to go for a look and were impressed by what they saw. Kelly says joining The Village made it easy to build green. “Everyone else is doing it, so you’re not standing out too much.”

The couple had been in touch with Galway-based passive timber frame specialists Scandinavian Homes about building a bunaglow on a site they were considering before. Scandinavian Homes has been supplying low energy homes – factory built in Sweden – to Ireland since 1991.

Once Kelly and his wife joined The Village, they adjusted their design to a two storey model to keep the same floor area on a tighter site, and to fit with the two storey buildings on the main street in Cloughjordan.

Though Kelly and his wife wanted a highly energy efficient home, they weren’t tied to the passive concept. Scandinavian Homes doesn't get their houses certified by the Passivhaus Institut itself – it leaves that up to its clients – but the firm aims to build homes with a tiny heating demand that have little or no need for conventional heating systems.

The company says the house will have a heating demand of less than 10 watts per square metre in the coldest Irish weather – and that they can get down to 5 watts per square metre for their super-passive bungalows. The house's simple cube shape is designed to reduce its surface area and thus minimise heat loss. Company director Lars Pettersson emphasises the importance of reducing heating demand as much as possible. “Then you can use electricity for heating with a conscience,” he says. “We have to be down to better than passive to do that.”

The house’s timber windows are triple-glazed and argon-filled with a low-e coating; a heat recovery unit ventilates the house

The houses’s timber frame wall build up features 215mm of mineral wool and a U-value of 0.16 W/m2K – a higher specification than the figure of 0.175 stipulated in SEI’s guidelines for building passive houses in Ireland. The roof features 700mm of cellulose – Pettersson says this will eventually compress to about 600mm – and has a U-value of 0.1 W/m2K. The attic hatch is also insulated to give it a U-value of 0.4 W/m2K.

The ground floor is insulated with 280mm of expanded polystyrene (EPS), with 135mm of EPS insulating around the perimeter of the foundation. The house’s windows are triple-glazed, and the thick 14mm and 15mm cavities are argon-filled with a double low-e coating and warm-edge technology.

An REC Temovex 400 HRV unit ventilates the house, and four Pex pipes in the foundation are used to distribute heat from the biomass district heating system if needed. The house boasts an air-tightness of 0.56 air changes per hour (ACH), inside the Passivhaus standard of 0.6 ACH.

Anthony, Elaine and their two kids moved in shortly after Construct Ireland visited the house in December last year. He says the house heats up easily inside when there’s just a bit of sunshine, and that even basic activities like cooking can heat it up quickly. “It’s amazing, we’re very impressed with it at the moment.”

Builder John Connolly worked as part of the team that completed the house. For Connolly, building passive makes sense. “Take an average house. If you’d be looking at spending e5,000 on a heating system, if you spend e5,000 on insulation you can nearly do away with the heating system.”

A fully glazed rooflight over the stairs helps to naturally illuminate the house

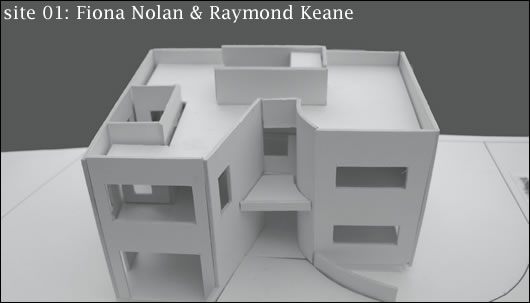

With what is expected to be the first house at The Village to be certified by the Passivhaus Institut, Fiona Nolan and Raymond Keane certainly have something to boast about. Nolan was skeptical about the cost of certification at first, but says she changed her mind after discussing it with her architect Paul McNally now of The Passivhaus Architecture Company.

The couple joined the eco-village about four years ago. They sold their house in Churchtown, south Dublin during the property boom, using the profit to pay for their build at The Village and for a smaller house in Dublin, where their two kids are still in school.

Their eco-village house was nearing completion when Construct Ireland visited in December. Architect Paul McNally, now of the The Passivhaus Architecture Company, has been told the house will receive Passivhaus certification once it's finished and he submits photos of the final detailing. His green renovation and extension of a hollow block house in Dublin was profiled by Construct Ireland in January 2009 (Volume 4, Issue 5).

The house at The Village is designed to maximise the features of the site, McNally says. Because the south-facing facade sits near the road, one of the big challenges was maximising passive solar gain with large windows without compromising privacy. McNally employed a few neat design tricks to balance the two. The curved approach path leads vistors to the deep-set front door and away from any windows, while the large south-facing windows and the living space are shielded by the wall of the house itself (see model). The only exposed windows at the front are intentionally smaller.

(clockwise from left) the windows are triple-glazed and Passivhaus Institut-certified; the house is clad externally with Aquapanel, supplied by Greenspan; the walls are heavily insulated with Thermohemp; and closed up with Fermacell

McNally chose triple-glazed, Passivhaus-certified windows from Optiwin with an overall U-value of between 0.71 W/m2K and 0.79 W/m2K, depending on size. A fully-glazed rooflight over the stairs helps to illuminate the house naturally. Rooflights typically sit on top of the roof to direct rain outwards, but this can create a cold bridge. To get around this, McNally installed a separate sheet of glass on the roof with a triple-glazed rooflight beneath. The top sheet deals with the weather while the triple-glazing beneath provides insulation.

Meath-based manufacturer A-Frame supplied the house's timber frame system. The company's Peter Creaney says that while they have done low energy buildings before, this will be their first to be certified passive. From the inside out the wall features Fermacell, an 80mm service cavity insulated with Thermohemp, taped and sealed OSB board, another 200mm of Thermohemp insulation, 60mm of Gutex followed by batons and a 60mm rainscreen clad with Aquapanel, a cement fibreboard with a much lower carbon footprint than conventional brick or block. At 0.129W/m2K, the wall's U-value is exceptional.

The flat roof's build up is similar, with Fermacell inside followed by a 50mm service cavity insulated with Thermohemp, an Intello vapour membrane from Ecological Building Systems, 250mm I-beam joists insulated with Thermohemp, OSB board, 100mm of Gutex Ultratherm wood-fibre insulation and a cross-battoned 80mm ventilated space below the roof surface. This gives a U-value of 0.106 W/m2K. The ground floor features a Supergrund foundation system with 300mm of Aerobord EPS insulation and a U-value of 0.11W/m2K.

The house scored an air-tightness result of 0.56 air changes per hour at 50 pascals - inside the Passivhaus standard of 0.6. A heat recovery ventilation system from Quality HRV is the main source of heating – the district heating network heats a coil in the HRV unit which then heats the air. McNally did specify a few radiators for inside the house too though.

Contractors Breakwater Construction – who specialise in low energy building – also built an extension to Nolan and Keane's Dublin home. Breakwater's Shane Adams previously worked for his father's building firm before striking out on his own – the last few jobs he did in his previous position were geared towards sustainability, and he became convinced that was the way forward.

Adams says any timber Breakwater use is certified as sustainable, unless something else is specified by the client or architect. He worked with the A-Frame system for Nolan and Keane's house, but Adams is happy to use whatever building system his clients prefer. "We want to use the best products that are available," he says.

As for Nolan and Keane, they say their main motivation for joining The Village was the community, but green reasons played a role too. Nolan says she has always been environmentally aware, but reckons it'll be much easier to be green at The Village. "You try to do whatever you can on your own green-wise, and it's much harder, whereas when everybody's doing it it's much easier."

If going green is the aim, a certified passive house is certainly a good way to start.

Selected project details

Architect: Paul McNally Ecological Architecture

Main contractor: Breakwater Construction

Timber frame: A-Frame

Windows & doors: Optiwin Ireland

Natural insulation: Ecological Building Systems

Air-tight membranes & tapes: Ecological Building Systems /Siga /Hyperseal

Insulated foundations: Supergrund

Internal wall board: Fermacell

Cement fibre Board: Greenspan

Heat recovery ventilation: Quality HRV

One of the most intriguing buildings to go up at The Village so far is the three-house terrace by EcoBuild Ireland, an angular two-storey structure limewashed in pink tones, albeit with the more rotund design by Michael Rice completing the terrace to the west.

The terrace's wall system – built by Tipperary-based MBC Timber Framebc Ltd – was insulated on-site with 200mm of Biobased spray-foam insulation, supplied by Econstruction Products. The walls have a U-value of 0.18 W/m2K. "It's a very breathable wall," says Ecobuild Ireland's Aidan O'Brien. The build-up also features Panelvent, a breathable external sheathing board from Ecological Building Systems.

EcoBuild Ireland applied a hemp-lime render – supplied by Monaghan based Hempire – inside and outside. O'Brien is eager to see hemp-lime move from the construction sidelines to the mainstream. "Ideally the hemp would have been grown in the field next door and not overly processed," he says, adding that importing established hemp-lime systems is probably necessary for now to kick-start the sector.

He weighs up the choice green builders face between timber frame and hemp-lime. "I suppose ideally you might have a fully hemp-lime wall, but with this you're sacrificing some of the hemp-lime for more insulating materials. So you have a slightly quicker build and quicker dry out, and slightly less cost."

EcoBuild Ireland installed a Passivhaus-certified Supergrund foundation system, which includes 300mm of expanded polystyrene (EPS) insulation. They used nine inches of BioBased spray foam to insulate the roof, which has a U-value of 0.18W/m2K. O'Brien is also planning to insulate the loft to boost the thermal performance further.

The double-glazed windows in the houses were supplied by CareyGlass and have a U-value of 1.3 W/m2K, but when it came to glazing light was as important as insulation for O'Brien. Most of the glass is on the south-facing facade. "It's very very clear clear glass, it lets in far more sunlight," he says. "If you used triple glazing with two layers of low-e on it, you wouldn't get the same [solar] gain. So the idea is to get a lot of gain in here to heat the floor, as opposed to putting in hugely insulated glass that wouldn't be letting in the same amount of light."

Heat is distributed through the houses by a Variotherm Easyflex wall-based system, with 11.6mm heating pipes installed in the walls. The system was supplied by Galway-based Real Energy, and the company's Kevin Devine says installing a heat distribution system in one of the cold points in a house – the external walls - can significantly improve indoor comfort.

A final air-tightness test had yet to be performed when Construct Ireland visited, and there was still some sealing left to do. The most recent provisional test had produced a result of 2.6 air changes per hour. Aidan O'Brien says there's no need for an air-tight membrane in the walls - the foam insulation expands to fill every nook and cranny. The foam will perform the same function in the roof, but O'Brien says a roofing felt here also acts a vapour membrane.

Builder Aidan O'Brien is an eco-village member himself and has just started the foundations on his own house

The houses feature heat recovery ventilation from Austrian manufacturer Vallox. O'Brien chose the unit because of its ducting system, with every duct leading from inside the living space directly back to the manifold. It requires more tubing but makes cleaning easier, O'Brien says, adding that it makes air delivery more controllable too.

The terrace is one of about 15 projects O'Brien and EcoBuild Ireland are working on - his other jobs are using building systems ranging from hemp-lime to Durisol, a type of block containing cement and wood fibre. O'Brien is an eco-village member himself and has just started the foundations on his own house, so perhaps it's no surprise he's emerged as the biggest contractor on site. "We cut the cost to try to make it happen," he says.

The terrace should be ready for the owners to move in early in the new year. Trisha Curran joined the eco-village in November 2008. She originally owned a site further north in the eco-village, but decided to take one of the terrace houses when she found out building was starting there. Having retired and lived in a small cottage in south Dublin without a garden, she was keen to move somewhere she could grow her own food.

The walls were rendered externally and internally with a hemp-lime mix from Monaghan-supplier Hempire

Community life was a big attraction for her, but so were green issues. "I would live very lightly on the planet," she says. "I like the idea of growing my own food and of being in a timber frame house. The materials that were used were fairly sustainable."

Mary Keogh, who's also retired, will be moving into the middle house. She joined the eco-village in 2007 after following its progress for a few years. She presumed all the sites had been sold, but when she came across an ad seeking members she didn't hold back. "I made a decision straight away, I knew this was what I wanted."

She certainly sounds excited about moving in. "It's the cosiness of it, the warmth of it. The insulation is wonderful, the air-tightness is done exactly to perfection. The heat recovery system to going to keep your air pleasant and fresh," she says. "You won't need a lot of heat."

The manifold for the Variotherm wall heating system

Selected project details

Contractor: EcoBuild Ireland

Hemp-lime render: Hempire

Foam insulation: Econstruction Products

Insulated foundations: Supergrund

Windows: CareyGlass

Wall-based heating system: Real Energy

Heat recovery ventilation: Vallox

For Peadar Kirby and his wife, moving to the eco-village had always seemed like a pipe dream. The couple has been active in the group planning the project in Dublin, but with Kirby working in the capital, moving to Tipperary wasn't an option. But that suddenly changed when he landed a job at the University of Limerick, just over 50km from Cloughjordan by rail and road.

Having lived in Dublin all his life, Kirby and his wife were attracted by the chance to live in a vibrant rural community. Environmental concerns were on their minds too. "For both of us the issue of climate change is a very major issue. Being involved with a group of people tying to model a more sustainable way of living was of great interest to us both," he says.

The couple would like to have hired an architect to design a house from scratch, but time wasn't on their side - after they closed their site purchase they faced a tight deadline to finish their design. "I was moving jobs and there was a lot else going on at the time," Kirby says. "The most practical thing was not to go to an architect and start designing from the beginning, so we began to look at houses you can effectively buy from the shelf."

Kirby came across a brochure for Austrian low-energy timber frame specialists Griffherhaus, in The Village office in Cloughjordan. The couple visited the company's show house and were instantly impressed. "We fell in love with the show house in Fermoy - the beautiful quality of wood, the quality of light."

"I suppose both of us would have loved the possibility of designing a house from beginning, but because that wasn't practical we decided to go with this," Kirby says.

From the outside-in the Griffnerhaus system features rendered bluclad board fixed to the main wall with batons and counter-battons, a breathable membrane, 20mm of fibreboard, 200mm studs insulated with cellulose, taped and sealed OSB board, a 50mm service cavity and finally, Fermacell internally. The wall has a U-value of 0.18 W/m2K. Griffnerhaus offer the option of insulating the 50mm service cavity too, though it wasn't done in this case.

The main roof section also features 200mm of cellulose in a similar build-up and has a U-value of 0.19W/m2K. Austrian manufacturer Hracho Wina supplied double-glazed alu-clad windows with a low-e coating, a 16mm argon-filled gap and a U-value of 1.18 W/m2K

As with all houses at The Village, an 800 litre insulated buffer tank stores hot water from the district heating system. An underfloor system distributes heat throughout the house, and there are two heating zones. The Kirbys can control the heating system manually, but it can also be set to knock on automatically if the temperature outside drops below a certain level. "It's a fairly sophisticated system," says Griffnerhaus's Adrian Lennon.

The timber interior is flooded with natural light

The house was still awaiting a final air-tightness test result when Construct Ireland went to print. Energy assessor Brendan Power of Acorn Energy, another eco-village member who's building a hemp-lime house, calculated a preliminary delivered energy consumption of 70 kWh/m2/year - a provisional BER of a B1. To boost the BER, Power suggests installing a thermostat upstairs to create a third heating zone for the BER calculation, though conditions upstairs can be set separately from a control panel in the utility room. Power also recommends doubling the number of low energy lights – currently half of all the bulbs – to help improve the rating.

For the moment, Kirby is dividing his time between his job in Limerick, Dublin where his daughter is still in school, and Cloughjordan. Once his daughter is finished school in a few years he and his wife will move down permanently. For now he's renting out a room in the house and trying to spend as much time there himself as he can.

He recalls one of his first mornings in the house. "We're south-facing so you get great light, that's what I experienced the first two nights I was there. I woke up to an absolutely glorious sunrise to the east," he says. "It's a really beautiful house."

Selected project details

House design and contractor: Griffnerhaus

Windows: Hracho Wina

Cellulose insulation: Homatherm

Internal wall board: Fermacell

Energy assessors: Acorn Energy

- Articles

- Case Studies

- Village green

- Eco village

- Griffnerhaus

- Aquapanel

- fermacell

- cellulose

- community

- Supergrund

Related items

-

Play to win

Play to win -

It's a lovely house to live in now

It's a lovely house to live in now -

Ecocel supplying English developer Bell Blue

Ecocel supplying English developer Bell Blue -

Ecocel on site with 56 homes in Cork

Ecocel on site with 56 homes in Cork -

Ecocel insulation has tiny carbon footprint, EPD reveals

Ecocel insulation has tiny carbon footprint, EPD reveals -

Cellulose insulation can boost airtightness — Ecocel

Cellulose insulation can boost airtightness — Ecocel -

Don’t neglect simple attic insulation — Ecocel

Don’t neglect simple attic insulation — Ecocel -

International: Issue 31

International: Issue 31 -

Tanzanian children's eco village aims to inspire low carbon example

Tanzanian children's eco village aims to inspire low carbon example -

Woodland wonder

Woodland wonder -

Phase one complete at UK’s largest passive scheme

Phase one complete at UK’s largest passive scheme -

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay