- Case Studies

- Posted

Wright On

With the building of a new house in Greystones, County Wicklow, Ireland has become only the third country to feature the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Jason Walsh visited the site to see if Wright's designs might just represent the kind of thinking required in today's energy-conscious buildings.

Tucked-away in the middle of the county Wicklow town of Greystones is a newly built house of unusual architectural significance. Built in 2007, the house, a remarkable two storey modernist affair, was completed a full forty eight years after the death of its designer, Frank Lloyd Wright.

Born in Wisconsin in the United States in 1867, Frank Lloyd Wright is surely one of the best-known historical figures in architecture. Now seen as America's greatest architect and a titan of modernism, it's easy to forget that Wright had a turbulent career, coming in and out of favour with blistering intensity.

Like his European modernist contemporaries Le Corbusier and Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Wright is an architect not only revered by his profession but also well-known to the public at large. Le Corbusier's work has come in for some criticism for its alleged 'dehumanising' properties – Wright's greatest contribution appears to have been to have combined the clean, rationality and democratic aspirations of modernism with architecture of a form and on a scale that humans can relate to. Unlike Le Corbusier, no-one ever describes a Wright building as totalitarian.

In part it appears to have been his humanism that appealed to Marc Coleman, the proud owner of Europe's only Frank Lloyd Wright-designed building, completed in late 2007 in Greystones: "It was so futuristic but also so human. Frank Lloyd Wright is the only deceased architect whose work people are still building," he explains.

Coleman's house, the first Wright design to be built outside of his native United States and Japan, is a late Wright design, dating from the final year of the architect's life, 1959. It was commissioned for Mr. and Mrs. Gilbert Wieland and due to be built in Maryland, USA but never was due to the Wieland's financial problems.

"The drawings sat there until I came along," says Coleman. "Wright's work is site specific and our site was almost identical, topographically speaking."

This is an important point. As an architect Frank Lloyd Wright didn't work on the 'cookie-cutter' principle banging out endless repetitions of his work without regard to their inhabitants needs or their location and site. Instead, Wright's work is, at least in part, defined by its site specific nature.

Not only that, but Wright's work is administered by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, a body that is fiercely protective of the architect's work and legacy.

Happenstance and good fortune played a central role in Coleman's choice of the design for his house. He contacted the foundation and explained that he wanted to build a Frank Lloyd Wright house and discussed the available options. Coleman says the foundation had a total of 380 un-built designs: "They trawled through them and offered us four. Three required extensive modification but this one was a perfect fit."

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation is not merely a charitable trust, but is in fact a body that was founded by Wright in 1940 at his famous Taliesin West home in Arizona, where it is still located today. Following on from the earlier Taliesin Foundation, the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation was endowed by Wright with all of his past and future designs, drawings, writings, and personal property including his homes, Taliesin in Spring Green, Wisconsin and Taliesin West. After his death in 1959 the foundation's members decided that one of their most important tasks was "to separate the Wright myth from the Wright legacy."

Today, the foundation describes itself as a "non-profit organisation dedicated to conserving the work of Frank Lloyd Wright and advancing the principles of organic architecture."

Coleman dealt directly with the foundation through E. Thomas Casey, an architect who trained under Wright. Having returned from the war, Casey studied architecture at the University of California, Berkeley and upon graduation in 1950 applied to work and study with Wright at the community of architectural graduates in Taliesin West. He was accepted and eventually went on to become founding dean of the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture at Taliesin West as well as working as the structural engineer on Wright's Guggenheim Museum in New York.

"When I called up the foundation it just so happened that Tom answered the phone," says Coleman, "and we struck-up an instant relationship. He agreed to be my consultant [on the project]. That was one of the conditions – I had to have a consultancy with an architect who survived under Frank Lloyd Wright."

Casey visited Ireland and spent three days on the site with Coleman before supplying 18 drawings from the Foundation's archive.

Sadly Tom Casey died in 2005, eighteen months before construction work was to begin on Coleman's house. Two other members of the foundation, Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, director of the Frank Lloyd Wright Archive and Oscar Munoz, continued the foundation's engagement with the project, as did Effi Casey, Thomas Casey's widow, also a disciple of Wright.

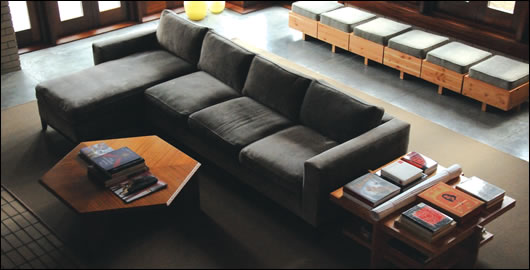

A total of 3,860 square feet, the internal layout of the house is centred on a large living area with a 13 foot 8 inch double-height ceiling. In addition the ground floor features some cellular rooms – a home office and a large bedroom while the first floor houses a further three bedrooms and a large landing area that Coleman uses as an ad-hoc, open-plan study. The kitchen area is located toward the front of the house on the ground floor, behind the main fireplace and chimney in the living area. "Wright was constantly pushing to design the one room house – he wanted to make the private spaces subservient to the main living area."

Wright designed the house around a four foot by four foot grid, proportioning relates the various areas of the house to one-another both vertically and horizontally.

The grid layout is something which Coleman is particularly enthusiastic about: "Everything is a multiple or a division of that grid. Mathematics, if they're got right, create incredible proportions and they also create a very tranquil sense in a building. An untrained eye may not know this or see it but they can feel it, they feel well in the building and that's why."

This is not as unusual as it may at first sound. Mathematics is at the heart of architecture, not only structurally but also aesthetically and has been for millennia. The golden section, for example, was used in classical architecture but Wright's contribution was to create a rational, unitised system.

In order to comply with Irish building regulations some changes did have to be made to Wright's design. As Coleman explains: "In America you're allowed to build a nine and a quarter inch cavity wall, in Ireland you're not – they have to be twelve inches."

However, this change was not allowed to disrupt Wright's design or the harmony that it promotes: "The inside of the external walls of the building all land exactly on the extreme gridlines of the footprint of the building. If you had a nine and a quarter inch wall then that wall would project nine and quarter inches past the gridline on the outside of the building. But in our case it projects twelve [inches] because that's our legal requirement in the building code in order to get the right insulation and cavity airspace."

Coleman points out that despite this adjustment made in order to ensure the building reaches contemporary Irish regulations, the essence of the design has not been changed: "The internal volume of the building and the exterior heights of the building are identical to what's called-up on Wright's drawings – we were able to build the house in its volumes exactly as Wright intended it to be built."

Building the future

Coleman's description of not only the house, but also the work on-site sounds remarkably like an act of love, perhaps unsurprisingly given that he has been fascinated with Wright's work almost to the point of obsession for years: "I would be considered something of a Frank Lloyd Wright expert. I've been interested in his work since I was eighteen. I did a degree in history of art and architecture and I've never gone away from Frank Lloyd Wright's work," he says.

Nevertheless, Coleman's expertise also means there was a demand for an attention to detail rarely seen in Irish building, but this was not a source of any conflict: "There was not one bad word spoken between any of us on the project. There was an absolutely open and transparent communication. We worked well as a team – there was a flow.

"Everybody understood the grid system and it was very easy for them then to work within an eighth of an inch, then, once they laid it out with lasers and sprayed it out with chalk, they could work to those lines and they kept data reference points all the way around the site.

"I spent two weeks looking at the drawings, figuring out the way everything had to be done before we actually commenced work. That investment in time meant we didn't make one single mistake in the building."

In fact, two weeks of planning is just the tip of the iceberg. Coleman spent three years researching the building and what materials would be used in its construction, sourcing materials that included two inch by twelve inch roofing timbers from Finland and three ply Douglas Fir timber from Germany for the internal walls.

Work started with the demolition of the existing house, a typical Irish dormer bungalow, on May 23, 2007. Construction started two days later and the basement was complete by September 4. Coleman and his family moved in to the house on October 23, 2008.

The attention to detail in the building all flows directly from Wright's designs, right down to instructions on how to treat the mortar between the bricks: "That's a classic Wright detail. He always specified that the horizontal joint [between blocks] be a raked joint in order to give a horizontal shadow and emphasise the horizontal lines of the building. He insisted that the vertical joints are flush-filled to the face of the brick. Each joint is supposed to be three eighths of an inch in order to work with the bricks so that you get six bricks and six joints to a four foot module.

"Another classic detail is he lets the fourth side of a window, in seven places in the building, [merge] directly into a reglet in the brick. These reglets had to be cut by hand in order to let the glazing unit directly into it. The reason he did that was to let the exterior material come cleanly through with no breaks so that you have a natural connection between the exterior and the interior."

Additionally, the glazing has no corner mullions, instead using mitred glass set at an angle of 45 degrees. "This was to break down people's concept that housing was a box you lived in. He wanted to open it out, bring in the outside and bring the inside outside in order for the house to be more organic and connected with nature."

The exterior walls are constructed from bricks that had to be specially made for the job due to the imperial measurements used in the design – 30,000 in total supplied by IBStock.

All the furniture for the house was designed by Wright and built to his specification by JDB Design Ltd.

Eco prototype

Coleman is adamant that Wright is more than just a great architect, but was in fact a prototype for today's ecologically sensitive designer: "Wright generally did not put in air-conditioning into his houses – he designed natural air ventilation systems, including in his own home in Scottsdale, Arizona. He liked to work with local materials rather than imported ones. He emphasised nature – he saw trees as man's greatest friend," he says. "I believe if he was around today he'd be fascinated by products such as Homatherm insulation and those kinds of things."

Both natural ventilation and the use of, as far as possible, locally sourced materials are carried through in Coleman's house. Additionally, the house makes abundant use of passive solar gains with its strategically placed glazing: "The sun path is always critical," says Coleman. As well as maximising daylight, the windows also afford a greater feeling of connection with nature, something that Wright both preached and practised: "It has an almost spiritual quality.

"The entire upper floor of the house has 360 degrees of windows – it feels like living in a tree house, the connection with nature is immense. Even in severe weather you have a tremendous sense of safety and shelter in the building."

Of course, this is a house that, fundamentally, was designed almost fifty years ago at a time when oil peak and climate change were unheard of. Designers at the time were oblivious to notions of energy efficiency and keeping carbon emissions to a minimum.

This is one reason why Wright is atypical. Other buildings of the era are more profligate in their energy use. No-one would claim that Coleman's house is of the order of a passive house, but taken in its own context it is remarkable – an architectural classic designed five decades ago, it proposes the house as an holistic experience, something that eco-architects and builders still strive for today.

Nevertheless, Coleman felt that he should continue and even update this aspect of Wright's vision by making the building as sustainable as possible without sacrificing the architectural vision that gave birth to it: "I tried to put as many eco-friendly substances and systems into the building as possible because I felt that Wright would do that – that's what he tried to do himself in his own time. He also pioneered underfloor heating, which is a really intelligent form of heating because it creates effectively a macroclimate in a building – there are no hot and cold spots, you get an even distribution of temperature everywhere."

The house has not undergone a building energy rating, having begun the planning process before they were mandatory, and overall calculations are not available. However, the u-values of the individual elements are known. "We did calculations based on the volume of the building and size of the glazing areas to achieve a 1.1 [m/2K] u-value," says Coleman. The glazing used is Glass Seal low-e Pilkington K SM glazing.

The cavity wall insulation is 60 mm of Kingspan Thermawall TW50 with a thermal conductivity of 0.023 W/mK and thermal resistance of 2.60 m2K/W, and a U-Value of 0.25 W/m2K.

The insulation in interior walls and the first floor is Homatherm, supplied by Ecological Building Systems, a slab insulation produced from recycled newspapers and wood fibre. Homatherm, designed and manufactured in Germany, was developed to provide effective thermal and sound insulation, regulate temperature while absorbing moisture and gently give it off again. Additionally its density provides protection against overheating during the summer months. Homatherm has a thermal conductivity of 0.040 W/mK and comes in thicknesses of between 30 and 180 mm.

The roof is insulated with Kingspan Thermataper TT46 external roof insulation. Kingspan conducted a calculation on the roof to determine the quantity roof insulation required to surpass building regulations.

The basement structure is insulated externally, with 100 mm Kingspan Styrozone insulation used beneath the basement floor slab and 80 mm Styrozone for insulating the vertical walls.

The concrete floors contain Low E-insulation with a 3 inch screed on top.

Central to the building's claim to energy efficiency is the use of a wood pellet system for space and water heating.

"I researched all of the available pellet systems and then I went to various trade fairs and looked at the stuff. At the end of the day, to me Windhager was the Rolls Royce," says Coleman.

The precise system that Coleman chose is a Windhager Biowin Exclusiv 260, a system with a maximum capacity of 25.9 kW and a minimum of 8.3 kW. It was supplied by Heatright, based in Skibbereen, Co. Cork.

Heatright's Colm McCarthy explains that the Windhager Biowin Exclusiv 260 is a premium system, the top of Windhager's range: "The Exclusiv has automatic feeding, automatic cleaning and ash removal as standard. It also has combustion control and automatic modulating," he says.

Automatic modulation means that the system runs particularly efficiently, adjusting from minimum to maximum output as required.

"We supplied the Windhager control system," says McCarthy. "The boiler gets a signal from the control system and works on that basis." The control system, known as Modular Energy System (MES), is weather-compensated and also controls the hot water. The boiler is aware of what temperature the heating system requires while the heating system is aware of what temperature the boiler is currently at. By working in tandem like this, efficiency is greatly improved: "It reduces the number of starts and stops and means a buffer tank is not always necessary, though one was used in this case."

In Coleman's house the Windhager system also fills a 250 litre hot water tank.

The system has an efficiency rating of 92 per cent: "Because of the controls and modulation – independent consumer agencies in Sweden gave it one of the big prizes – it remains at 92 per cent efficiency all year, not losing efficiency at any time."

"The Windhager system is chosen, first of all, from a sustainability point of view and a carbon point of view – it's carbon neutral and timber is sustainable and replenishable," says McCarthy. "Practically, you can use your fuel whenever you want, not just when 'rates' are cheap as with electricity. The fuel is good value – it's far cheaper than oil and gas or any fossil fuel.

McCarthy is also keen to point out other benefits to the system: "We offer the same five year parts and labour warranty as Windhager in its native Austria. It's a low maintenance system – it only needs to be cleaned every four tonnes of fuel."

As the house has not been inhabited for very long Coleman is not yet able to calculate his annual fuel bill: "It takes almost three years for a masonry constructed house to fully dry out, just the moisture from construction. Nevertheless, it's cheaper than oil. Once it has settled down it should be around five tonnes of pellets a year." At today's prices that would equate to around e900 annually. Currently the system is running at 30 per cent of its capacity.

Coleman is more than satisfied with the Windhgaer's performance thus far: "It's fantastic – I'm delighted," he says. "There's an air temperature of 21.5 – 22 degrees in the basement. You can go around in a t-shirt. It's also completely quiet."

To top off his commitment to energy efficiency, Coleman has specified low energy lighting throughout the house and is currently contemplating switching to a renewable electricity supplier.

Modern life

A classic design, some technological updates, years of planning and months of building and the house is now complete. Much could be written about Frank Lloyd Wright – and indeed has been – and undoubtedly much more will be written, perhaps including on this new building, but as a self-build project, albeit an unusual one, the main question to be asked right now is: does the house live up to expectations? Is Coleman happy to be living there and is he glad he built it?

"We absolutely love it. Wright really didn't just design a house, he designed a way of living. He wanted to dismantle the formality of Victorian buildings where people had huge private suites. He was constantly trying to break barriers and create a new, more casual way of life."

In the case of this unique house in County Wicklow, built almost fifty years after it was designed, Wright certainly succeeded. In its promotion of a way of life that is not only informal but ultimately sustainable Wright's design holds its own with anything that has come along since. Ahead of his time is a phrase that is used too often, but in this case it might just fit.

Project details

Design: Frank Lloyd Wright,

the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

Architect of record: CMB Design Group

Planning consultant: Tom Creed Architect

Main contractor: James N. Earls & Sons & Daughter Ltd.

Basement construction: Future Build Systems

Mechanical and Plumbing contractor: Abacus Plumbing Services Ltd.

Electrical contractor: AB & Sons

Heating system: Windhager system supplied by Heat Right

Cabinet making and specialist woodworking: JDB Design Ltd.

Wooden flooring: Hardwood Floor Company

Glazing: Rich Glass

Joinery: Y2K Services Ltd.

Landscaping: Bespoke Gardening

Interior insulation: Homatherm supplied by Ecological Building Systems

Roof and external wall insulation: Kingspan Insulation

Bricks: IBStock

Roofing: Trocal system supplied and installed by Audsley Roofing

Firegrate (Wright-designed): Bushy Park Ironworks

- Articles

- Case Studies

- Wright On

- Frank Lloyd Wright

- Ireland

- Cellular Rooms

- Homatherm

- insulation

- Cavity Wall

- Windhager

- architect

Related items

-

Peaky blinder

Peaky blinder -

History repeating

History repeating -

King of the castle

King of the castle -

Energy poverty and electric heating

Energy poverty and electric heating -

New Ejot profile cuts thermal bridging losses by 25mm insulation equivalent

New Ejot profile cuts thermal bridging losses by 25mm insulation equivalent -

Build Homes Better updates Isoquick certification to tackle brick support challenge

Build Homes Better updates Isoquick certification to tackle brick support challenge -

Flat earth

Flat earth -

Material matters - A palette for a vulnerable planet

Material matters - A palette for a vulnerable planet -

Derelict to dream home

Derelict to dream home -

Final opportunity for construction professionals to secure 80 per cent training subsidies

Final opportunity for construction professionals to secure 80 per cent training subsidies -

Big picture - Points of access to resilient living

Big picture - Points of access to resilient living -

Storm breaker

Storm breaker