- Design Approaches

- Posted

Safe as Houses

Conventional wisdom dictates that higher construction costs—for instance to reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions—would either squeeze developers’ profit margins or increase house prices. Tom Dunne, Head of DIT’s School of Real Estate and Construction Economics, reveals how misguided this view could be...

From an energy efficiency perspective it must be clear to everyone that the insulation standards of newly built houses should be increased rapidly. There may be a fear that were this to be done this would increase construction costs and hence the price of houses. Is that fear well founded? I do not believe so.

In urban housing markets increased construction costs cannot be that easily passed on in the form of higher house prices. I appreciate that for many this may not appear to make sense and runs against common intuition about the operation of markets. I believe that a better understanding of how urban house markets work would clarify some of the issues involved in the determination of house prices. In turn this would facilitate the introduction of higher standards of energy efficiency in newly built houses.

House prices have been a topical issue for a number of years and attract much discussion in the media. Since the 1990s there also has been much serious research into housing and the phenomenon of exceptionally high prices. From the Bacon Reports of the late 1990s to the NESC study of late 2004 and a plethora of research reports from academics, estate agents and financial institutions the level of understanding of the operation of housing markets in Ireland has improved considerably. This must be good for the future operation of the market and will allow more sophisticated judgements to be made about housing policy including that about standards of insulation and energy efficiency.

I think it is fair to say that this increased analysis has already improved the quality of policy responses from government on housing, often a very contentious issue where a populist approach can be politically attractive. Importantly this has meant that government has refrained from introduction of measures which have a superficial attractiveness but would either distort the operation of the market or simply have resulted in further price increases; larger grants to first time buyers which would simply be passed back to developers, being a case in point.

Another more recent example of a more sophisticated understanding of the market influencing government thinking was the response by the Minister for Finance to calls for the removal of stamp duty in this year’s budget. Whatever about the merits and demerits of the case for doing this, at least the effect of doing so on the price of housing and the distribution of the gains were part of the explanation the Minister gave, indicating a more sophisticated approach to the market than in the past.

This more sophisticated understanding is also facilitating the introduction of higher standards of construction in Dun Laoghaire Rathdown and Fingal where decisions have been taken to increase standards without an outcry that the effect will be to increase the price of housing in their areas. If legislated for by government on a national level, a dramatic increase in house building standards, and in particular insulation standards, could be achieved without affecting house prices. It may appear contrary to economic logic to say this but consider the following.

It must be acknowledged that saying that the cost of production, or building in the case of houses, could go up without a consequent price increase, does not accord with most peoples’ understanding of the operation of markets. This is because most people have a learned understanding of the operation of the law of supply and demand where an increase in costs to producers tends to result in increased prices. This law is thought to be universal in its operation and reliably predictive, telling us what will happen in response to changes in the market place. The law of supply and demand is very strongly embedded into our understanding of how markets function and we assume that all markets work to this law in the same way. The law now forms part of an important belief system that allows people to understand how the world works.

In a recent obituary in the Economist it was said that Ralph Harris, who was the general director of the Institute of Economic Affairs—a hugely influential think tank underpinning the Thatcher revolution in the UK—wrote that the law of supply and demand was the nearest social science approached to the laws that governed the universe. He was probably not wrong. The law of supply and demand is firmly part of how we see the world. It is, therefore, not surprising that we expect that an increase in the cost of producing something will generally lead to a price increase in the market. But all markets may not work in precisely the same way and housing markets are something of an exception. This is often not appreciated sufficiently by the public generally.

Consider the following. In urban areas the supply of newly built housing is limited and is only a small percentage of the existing stock of accommodation. This has a major effect on the functioning of the market. In such a market demand for housing is primarily met from the existing stock with a very limited additional supply coming from developers. The price is, therefore, determined by demand for the existing stock which does not cost money to produce in terms of labour and materials.

This can be clearly seen in a city such as London where there is very little supply of new housing relative to the demand and the cost of construction is only a fraction of the market price of existing houses. This is similarly the case in Dublin at present where the cost of construction of a three bed semi-detached house could be about a third of the value.

Of course the difference will be found in the cost of the land.

This is where we come to an issue which is much disputed and on which there is no definitive wisdom as is the case of the law of supply and demand. Starting from the point that it is the demand for the existing stock that sets the price of houses in urban areas, it is argued that the cost of land is simply that which is left over after all the other costs of development have been deducted from the market price. The land or site for the house does not cost anything to produce in terms of labour and materials. Cost, therefore, cannot be related simply to the cost of production.

This suggests that developers approach the market for land on the basis that, given the market price of houses, the amount they can afford to pay for land will be determined by how much it costs to build profitably. Hence land is a residual and the price determined by the price of houses.

The NESC report “Housing in Ireland: Performance and Policy” (November 2004) considered this issue in some depth and suggested that neither the idea “that high land prices are the cause of high house prices” nor the idea that “high land prices are the result of high house prices” provides a full explanation of the relationship between land prices and house prices. So there is uncertainty here to say the very least, about the cost of land together with the cost of construction driving house prices in urban markets.

That being so it can be concluded that the assertion that increasing the cost of construction by improving energy efficiency standards will lead to an increase in the price of housing is, at the very least, a contestable issue. On an alternative analysis the assertion does not stand up. Certainly in my view, in the Dublin market, if the standards to which houses are to be built were increased radically there is no surety that the price of houses would go up on that count alone.

When faced with alternative views of what will happen in markets it can be useful to examine what actually happens in practice.

Commenting on the real estate market in the US recently where some prices have been falling, Global Insight—a leader in economic and financial analysis, forecasting and market intelligence for more than 40 years—said that “Builders do not like lower prices because it sends the wrong signal to potential buyers. Instead of cutting prices builders are adding extras—a larger bathroom, a fancier kitchen or even a cash rebate—to seal the deal”.

As an aside it is worth pointing out that if the conditions in the Irish market deteriorate, similar approaches to maintaining sales will be adopted by Irish developers.

Think about the point made by Global Insight for a moment as it is instructive.

In a market where prices are declining builders are increasing the cost of production of the units they are selling! The cost of production is going up and prices are declining.

What might be concluded from this is that the costs incurred by builders/developers do not necessarily increase house prices. To say the very least, there is no sure cause and effect relationship here as might be thought by many with a conventional understanding of the operation of the law of supply and demand in the house market.

Those that put forward the argument that increasing insulation or other standards will increase house prices should, therefore, be challenged to produce the evidence for this and the economic theory that backs this assertion up.

The alternative view is that in a buoyant market the cost of meeting increasing standards will come from lower land costs or developers profits.

The better understanding of the operation of house markets that now exists due to the plethora of comment and analysis can bear fruit. A greater understanding of how house markets operate will allow more people to challenge those resisting a change to radically increased standards of insulation and energy efficiency. There is something to be got for the environment from all the analysis of the housing market.

Maybe if newly built houses become more difficult to sell as conditions in the market change, developers will offer increased energy efficiency as an incentive to purchasers to buy newly built housing rather than an existing house. In those circumstances just maybe developers will be delighted to absorb the costs of building houses with radically improved standards of energy efficiency.

Tom Dunne is the Head of the School of Real Estate and Construction Economics, DIT Bolton Street. He is a chartered surveyor and Fellow of the Society of Chartered Surveyors, a Fellow of the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors and a Fellow of the Irish Auctioneers and Valuers Institute.

Early in his career he spent ten years working in one of the leading firms of estate agents and property consultants in Dublin. For the past twenty years he has been teaching property valuation to undergraduates and postgraduates studying in the fields of urban and property economics.

He is a former Chairman of the Society of Chartered Surveyors, the leading professional body representing professionals in the construction and property industry in Ireland

- house prices

- real estate

- construction economics

- fingal

- property

- brian cowen

- energy efficiency

- energy performance

Related items

-

Energising Efficiency

-

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced -

International passive house conference kicks off

International passive house conference kicks off -

Grant launches online learning academy

Grant launches online learning academy -

We can launch a new eco renaissance

We can launch a new eco renaissance -

Towards greener homes — the role of green finance

Towards greener homes — the role of green finance -

Viessmann launches new compact heat pump

Viessmann launches new compact heat pump -

New issue of Passive House Plus free to read

New issue of Passive House Plus free to read -

Saint Gobain launches online technical academy

Saint Gobain launches online technical academy -

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries -

An Post to enter retrofit market

An Post to enter retrofit market -

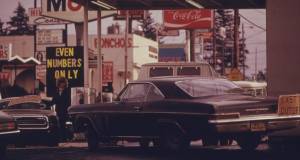

The first oil crisis

The first oil crisis