- Opinion

- Posted

Default setting

The Irish government’s response to the banking meltdown has increased the likelihood of Ireland defaulting on its debts, Richard Douthwaite argues, to the point of inevitability – a crisis that may only ease with the introduction of a new currency.Can Ireland avoid a default? Coming up with an answer is complicated by the fact that debt counsellors always have trouble getting their clients to admit the full extent and seriousness of their situation and countries are no different.

For example, it was revealed in mid-February that the Greek government had paid two Wall Street firms, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, to help it keep a lot of its borrowing off its books so it could circumvent EU rules. Our government is no better. It has set up a “special purpose vehicle” so that the billions that Nama will borrow won't be treated as part of the national debt although, of course, it actually is.

More seriously, the Irish government has refused to regard as part of its own debt the debts it took on when it guaranteed the banks. BNP Paribas figures show that the bank guarantees amount to €480 billion, equivalent to 244% of our national income. If you add in the amount the state owes directly, over €77bn and rising every second (the national debt clock at http://www.financedublin.com/debtclock.php is truly frightening), the total debt for which the government is responsible comes to just under three times the nation's income.

The huge chunk of national income required to service this €557bn debt has either to be earned by the banks or collected in taxes. If the banks make losses – as they will continue to do for several years until the mess left by the property bubble is cleared up – the government will not only have to cover any interest shortfall but borrow more itself to replace their missing capital. This extra borrowing obviously adds to the country's interest bill the following year, making the situation worse.

As a result, it is impossible for the country to support its current level of debt. A quick-and-dirty calculation shows why. If the average interest rate at which the government and the guaranteed banks are borrowing is around 4% and three times national income has been borrowed, roughly 12% of the country's income gets swallowed up in interest payments. This percentage would go up if the interest rate rose, of course. Such a rise is likely because, whatever happens to international rates, we can expect lenders to become increasingly reluctant to put money into an over-extended country.

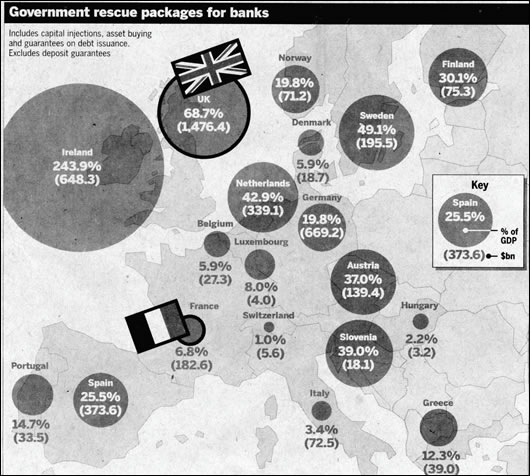

A map of Europe published in the Financial Times in February shows how highly invested Ireland is in the government’s bank rescue packages

A game Ireland can't win

It's a game the state can't win. Last year, the National Treasury Management Agency paid €2.5bn, equivalent to 7.7% of the state's total tax revenue, in interest on the (then) €75bn national debt. If that same low interest rate (3.3%) applied to the whole €557bn, (The rate at which the country was borrowing at the end of February was about 4.6%) about 57% of all taxes would be required – provided the tax-take stayed the same. But of course it wouldn't. If the government introduced spending cuts sufficient to enable it to pay over half its income to its creditors, the total tax revenue would collapse.

If this argument isn't enough to convince you that a default is unavoidable, consider this: the joint World Bank/IMF/BIS database figure for this country's total external debt shows that at the end of last September, Ireland owed $2,397bn to the rest of the world. That's about $600,000 for each man, woman and child in the country or, to put it another way, ten times our gross domestic product. This compares with €1,671bn at the end of 2008 and a mere €504bn at the end of 2002. According to IMF data, even at the end of 2007 Ireland was the most heavily indebted country in the developed world in terms of the ratio of private sector, household and corporate debt to GDP.

The government hopes that, if the global economy recovers, a surge in demand for Irish exports and an increase in foreign investment will save the situation by bringing money into the country. Some of this money would find its way into the government's tax coffers. Its bill for unemployment payments would be cut, and, with more money about, the banks would do better and present the state with lower bills for their bad debts. In short, the government would not have to borrow so much. Lenders would see that the tide had turned and continue to support the country. The risk of default would recede.

Such is its interest in the area that Goldman Sachs' chief operating officer, Gary Cohn – pictured here at the 'Managing Global Risks' session at the World Economic Forum meeting in Davos, in January 2009 – has visited Athens twice since November to pitch debt products, and has met the Greek prime minister, George Papandreou

I can't buy this scenario. If the world economy begins to grow again, the demand for energy will rise. As a result of inadequate investment in developing new supplies, this will push up the price Ireland has to pay to import its fuel, and the payments would compete for the euros we require to meet our interest bill. Moreover, as Ireland's best export customers and sources of investment are highly indebted too – the US debt is 390% of its GDP, for example – their recoveries will also be squashed by their higher energy bills. The world economy will never again have a period of rapid growth which is long enough for us to get our foreign debts down to a manageable level.

My view is that this country's economic life will carry on breaking down month by month. Domestic demand will continue to shrivel as a result of wage reductions, higher taxes and the public's reluctance to spend because of the high level of uncertainty and the cancellation of state and private projects. With their markets slipping away, more companies will collapse under the weight of their debts. Figures released by ICC Information in February show that 21% of trading companies already have a ‘negative net worth’. In other words, their balance sheet liabilities exceed the value of their assets. Their collapse will throw thousands out of work and many more mortgage holders into arrears. The banks will suffer huge losses as their bad debts mount and will need billions more in state support.

Those still in work will save all they can to build themselves a safety cushion. This will starve the economy of its monetary life-blood as the banks which take in their savings will be unable or unwilling to lend the money on.

With a much reduced tax take, the government will be unable to reduce its borrowing despite its recruitment embargoes and harsh spending cuts. Its higher social welfare bills and the cost of recapitalising the banks and meeting Nama's needs will see to that. Potential lenders will see what's going on and demand an increased rate of interest on their money. This will make the state's position worse and require it to borrow more.

So I expect several miserable months of increasing difficulty to pass until, all of a sudden, something happens which means that the National Treasury Management Agency is unable to sell new bonds to raise the money it needs to repay ones that are about to mature and Ireland will default.

Two possible ways out

Short of a massive increase in exports and foreign inward investment, only two unlikely events can prevent this. One is that the European Central Bank abandons its orthodoxy and uses quantitative easing to create money out of nothing and gives it to eurozone governments to enable them to pay off a significant proportion of their debts.

There are two problems with this. One is that, if the money was only given to states with severe debt problems, the “moral hazard” argument would be raised by the financially-cautious ones excluded from the distribution. “The recipients are being rewarded for their profligacy” they would say. A solution might be to allocate the money on the basis of population – so much per head. However, to be effective, this would require such large sums of money to be created and distributed that it would raise fears of inflation.

An inflation could happen this way. When the u institutions which had lent money to eurozone governments got it back, they would want to lend it out again. Most probably, they would have to do so outside the eurozone because, thanks to the ECB, the governments within it would no longer be looking for loans. The institutions would sell their euros for foreign exchange. This would push the value of the euro down, restoring the competitiveness the zone has lost since a euro was worth less than a dollar. The zone's exports would boom and imports would fall as they would become more expensive. The increased exports and lower imports would boost the zone's manufacturers' order books. Employment would rise.

Very probably, the effect on wages and prices would be limited as there's a lot of unemployment and spare industrial capacity. However, if the extra demand did cause a significant inflation, it would be a very good thing as, by raising their wages, it would make it easier for people to service their debts. Businesses would also be helped because their debt burden would be lowered in real terms. As a result, Irish banks would find that they had fewer bad debts and needed less support from the state, which itself would have additional tax revenue, reduced social welfare costs and a lower interest bill because of its lower debt.

While David McWilliams (above) has proposed that we leave the euro, others such as Prof Charles Goodhart (below), of the London School of Economics, point out that this would cause an immediate banking crisis

All in all, a very positive scenario but one which won't happen because of the widespread feeling that it is somehow improper to create money and give it away. Instead, the ECB is likely to offer loans to hard-pressed governments to enable them to stagger on but, as these countries already owe massive amounts of money, the new loans won't solve the problem at all.

The other unlikely event which might rescue Ireland would be Germany leaving the eurozone itself in order to avoid having to use billions of its taxpayers' money to bail out the PIIGS – Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain – or Club O'Med as they are beginning to be called. The main proponent of this idea seems to be Ambrose Evans-Pritchard of The Daily Telegraph, the doomiest economic writer I know. He writes that the departure of Germany, Holland and a few others would bequeath “the legal carcass of EMU to the Club Med bloc.

“This is the only break-up scenario that makes much sense,” he continues. “A German exit would allow Club Med to uphold contracts in euros and devalue with least havoc to internal debt markets. The German bloc would enjoy a windfall gain. The D-Mark II would be stronger. Borrowing costs would fall. The North-South gap in competitiveness could be bridged with less disruption for both sides.”

What happens when Ireland defaults?

One cannot predict exactly what will happen when Ireland defaults because the money system depends on confidence and it's not clear how much of that would be lost. My view is that Bank of Ireland and AIB will quickly find themselves defaulting too because the state guarantee would become valueless and they would become unable to borrow. A lot of imports would then be stopped because overseas banks would refuse to honour letters of credit from the two banks.

The non-guaranteed banks would anticipate this and refuse to credit their customers with payments made by anyone with an account in a guaranteed bank. As this embargo would include the state, social welfare payments and public sector wage cheques would be kept in limbo until new guarantees or some other sort of confidence-building measure had been put into place. The defaulting banks are likely to be given away with the promise of a tax-funded dowry to international banks with solid reputations, and an international organisation, probably the IMF, will probably move in and guarantee government payments.

Unfortunately, while the takeover of the two big banks and the hand-over of the economic management of the country to the IMF would allow economic life to struggle on, it would not solve the underlying problem, because the country's debts, public, corporate and personal, would be unaffected. If a country with its own currency defaults, it normally devalues its currency both to improve its competitiveness and allow space for an inflation to bring incomes more in line with domestic debt levels and excessive asset values. It also negotiates with its creditors to write down the value of its foreign debts. Ireland can neither devalue nor renegotiate its debts as it is trapped in the euro system, which lacks both an escape route and a rescue mechanism.

So the nightmare would go on. In the absence of the collective debt write-down and inflation that a devaluation provides, the only way that the private debt burden can be lifted is by individuals and companies going bankrupt and having most of their debts written off. Their assets would be sold at very low prices since no-one would be willing to pay much in the throes of an economic collapse. After a decade or more of misery, the individually-negotiated write-downs would return the total debt-to-national-income ratio to a supportable level at which asset values might be a tenth of their level today.

The country would be wrecked by this process. Education and health care would suffer savage u cuts. If it survived, the social welfare system would be a shadow of its current self and the brightest and best of the population would leave for pastures new. Many buildings would be abandoned and others would fall into disrepair since no one would be able to afford to maintain them. Some rail lines would close and many local roads would be barely usable.

Before that stage was reached, however, there would be massive demonstrations demanding new solutions. What might these solutions be? One, which has already been proposed by David McWilliams and others is that we leave the euro. That's not easily done. It's not just a matter of printing new Irish pound notes and minting coins. As Professor Charles Goodhart of the London School of Economics and Dimitrios Tsomocos of Oxford University pointed out in the Financial Times recently, no country can sensibly plan to leave the eurozone, because “any sniff of thinking about that would cause an immediate banking crisis.”

Moreover, Ireland's existing debts are denominated in euros and any attempt to renege on those would probably result in the seizure of the country's assets abroad. Remember that Britain used anti-terrorist legislation to seize Icelandic assets when that country defaulted. Anything valuable with an Irish government connection could conceivably be seized to use as a bargaining chip. Aer Lingus planes could be impounded when they touched down almost anywhere abroad.

The least bad domestic option

The Goodhart/ Tsomocos prescription for Ireland would be that the government should issue a new currency, (let's call it the punt), and use it for public sector wages and social welfare payments. It would pass a law making its new money acceptable for all internal payments between Irish residents, but not for any external payments between Irish residents and those living abroad. Taxes would be the only payments within the country for which punts could not be used.

On the day that the new money was introduced (and it would have to be done with great secrecy) our bank balances in Irish banks on the one hand and our outstanding loans to them on the other would be switched to punts on a one euro equals one punt basis. Rents, private sector wages interest and loan repayments to Irish residents would then be made in punts. However, loans from and deposits in foreign banks would stay in euros and anyone who had borrowed from one of them would still have their euro debt.

Because taxes would still be paid in euros, the government would get a lot of them in. It would transfer these to the Central Bank and ask it to manage the punt/euro exchange rate so that it eventually stabilised at a level that represented, say, a 25% internal devaluation. This target figure would limit the number of punts that the government could spend into use.

As Goodhart and Tsomocos point out, all external monetary relationships, including interest payments, would remain unchanged so no-one overseas would be upset by what had happened. All internal price/wage relativities and tax rates would remain unchanged but the enhanced activity would raise government revenue, and there would be a reduction, as measured in euros, in the state's interest, wages and social welfare bill for payments to Irish residents.

“It would be messy, and an unattractive dual currency mechanism,” Goodhart and Tsomocos write, without mentioning Ireland specifically. “But it could work; it has done so before now in other countries and circumstances. It might be the least bad option.”

My view is that there would be a constitutional challenge to the re-designation of the money in people's bank accounts as punts rather than euros on the basis that the punts were an inferior currency that was going to decline in value. But this challenge would come after the event. By the time the Supreme Court's judgement came through, the economy should be beginning to improve, requiring more punts to go into circulation to lubricate the higher level of activity. If so, the government could use some of them to compensate bank account holders.

The big advantage of the new punt would be that, as it would not be borrowed into circulation, it would not disappear when debts were repaid. Consequently, no-one would have to borrow punts to get them back into use. The new units would just go round and round from account to account indefinitely, making our currency system much better suited to a no-growth or contracting economy than it is today. It would not even be necessary to issue punt notes and coins, at least at first, as euros would still be in use.

The only problems I can see are that:

1. The government could spend too many punts into circulation, particularly if an election was due, and this could cause an excessive rate of inflation, just as government-created money did in Argentina in the 1980s, when prices rose by over 5,000% in a single year. However, this danger could be removed by having an independent Central Bank tell the state how many punts it could issue.

2. Our massive external debts would be unaffected and we would have to devote a major part of our export earnings for many years to paying them off. This would reduce living standards, of course, but at least we could have something close to full employment.

Unfortunately, I can't see any government having the guts to adopt this solution. So, if nothing is going to be done at either the European or the national level, communities will have to come up with solutions themselves. There's a lot of interest in community currencies at present especially amongst Transition Town Initiatives. One transition group, Future Proof Kilkenny, is working with the city's chamber of commerce and the Mayor's office on a plan for a debt-free electronic currency. If this goes ahead, it will be completely different from anything else in the world. I'll write about it in the next issue.

- Articles

- Opinion

- Default setting

- douthwaite

- Feasta

- economy

- recession

- NAMA

- National Debt

- National Treasury Management Agency

Related items

-

Green shoots for green building

Green shoots for green building -

Green groups critical of latest budget

Green groups critical of latest budget -

Passive house costs falling, new study finds

Passive house costs falling, new study finds -

Reaching for the first rung

Reaching for the first rung -

Green finance must be longterm & sustainable — Ecology

Green finance must be longterm & sustainable — Ecology -

Why housing isn't viable

Why housing isn't viable -

Passive house or equivalent - The meaning behind a ground-breaking policy

Passive house or equivalent - The meaning behind a ground-breaking policy -

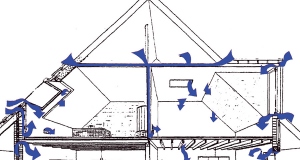

District heating and passive house - are they compatible?

District heating and passive house - are they compatible? -

How to stimulate deep retrofit

How to stimulate deep retrofit -

Delivering passive house at scale

Delivering passive house at scale -

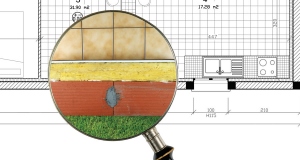

Material impacts

Material impacts -

Airtightness - the sleeping giant of energy efficiency

Airtightness - the sleeping giant of energy efficiency