- Renewable Energy

- Posted

Measured efforts

Earlier this year constructireland.ie broke the news of the introduction of the pilot Home Energy Saving Scheme, a new grant funding programme designed to stimulate the en masse refurbishment of Ireland’s poorly performing existing housing stock. John Hearne travelled to one of the pilot areas to see how the scheme is working on the ground, and discover how the scheme is developing.

One of the most striking characteristics of the Home Energy Saving Scheme (HES) pilot projects is the speed with which they’ve been rolled out. The three regional initiatives were announced in April, and the cluster version barely a month ago. Yet the plan is to have all works complete and all results fully collated by the end of November.

In the kitchen of her farmhouse in Lorrha, North Tipperary, Margaret Murray, who applied under the North Tipperary pilot, says she assumed the date on the form was a misprint. “I thought they must mean November ‘09, not ‘08.” Paul Kenny of the Tipperary Energy Agency, the technical partner to North Tipperary County Council, who are running the scheme in this neck of the woods, explains that the stakeholders need to know what kind of value they’re getting for the e5 million earmarked for the regional pilots, before they parcel out the remaining e95 million committed for national roll-out under the Programme for Government. For the householder, that means getting the works sorted quickly. But behind the scenes, the effort required to get the administrative backbone to support the scheme in place ahead of this year’s budget has been huge. “SEI were instructed to roll out the scheme and do it as quickly as possible.” Paul Kenny explains. “They didn’t have a lot of time to mull it over and think about it. They were told go start up a scheme that has a huge administrative burden”.

The Home Energy Saving Scheme is designed to target older housing – nothing built later than 2002; the logic being that these are the buildings most in need of energy makeovers. 1,500 homes across North Tipperary, Limerick, Clare and Dundalk form the regional core of the pilot, while the additional strand (covering 500 houses) will allow for ‘clusters’ of housing spread throughout the country.

An SEI home energy assessor – as distinct from a BER assessor, given that assessments will not include official BERs during the piloting phase – comes to your house, rates it and advises on works that need to be carried out to improve energy efficiency. The householder pays e100 towards the cost of the assessment (the full price is usually around e300-e500) and SEI covers the rest. Thereafter, 30 per cent of the works recommended by the assessor are paid for by government, to a maximum of e2,500. Launching the scheme, Minister Ryan said, “Of the 1.7 million homes in Ireland, it is estimated that up to 1 million require some investment to improve their energy efficiency. This scheme will support homeowners who wish to invest in their homes to bring them up to modern energy efficiency standards. Such investment has been shown to pay for itself in energy savings in a few short years. This scheme will help Ireland meet our climate change targets at the same time as assisting the householder with energy costs. Householders will save on their electricity and heating bills; they will use their energy more wisely and increase the re-sale value on their homes. The scheme will also be welcome news for the house-building sector.”

SEI estimates that householders will save up to e500 in their energy bills every year and that the scheme will save 6,000 tonnes of CO2 in its first year alone. The full e100 million scheme is expected to yield greenhouse gas savings of 175,000 tonnes per year.

In Lorrha, County Tipperary, Margaret and Francis Murray say they applied because they wanted to see how efficient the house was. Their heating load is borne primarily by oil, but heavily supplemented by turf, which they harvest themselves on their own section of bog. “We put down a good fire.” says Francis, but adds that with the prohibition on turf harvesting imminent, not to mention the escalating price of oil, energy efficiency has become increasingly important to them. “We do burn a lot of turf – more than seven or eight tonnes a year. If we were to buy it, it would cost us a fortune.”

Margaret and Francis Murray

In addition to the open fire in the living room, a solid fuel Stanley range supplements the radiators and domestic hot water requirements. The range, says Francis, is old and doesn’t perform. “It’ll handle four radiators okay, but turn on a fifth and the heat dies. You go up and take one bath, and all the hot water’s gone.” Apart from on/off switches, there are no heating controls, an immersion looks after much of the hot water needs, especially in summer, while the copper cylinder lacks a lagging jacket.

Home energy assessor Stephen Harte of ERI explains that, as with new houses, the DEAP (Dwellings Energy Assessment Procedure) methodology is used to calculate the energy performance of the house. “What we’re doing is we’re working out heat loss through building fabric which is the walls, windows, roof and the floor, and also heat loss through ventilation, whether that’s chimneys or natural ventilation; whatever’s in the house. Then we look at the heat required to heat the house based on the efficiency of the heating system and heating controls. You’re also looking at lighting, what percentage energy efficient lighting you have; that all plays a part in determining your energy value and CO2 emissions for the house.”

Harte will also be looking at ESB bills. Though electricity usage – with the exceptions of lighting and the pumps and fans associated with heating systems – isn’t considered as part of the BER process, or indeed the HES scheme, it is under a separate, though parallel scheme in which Tipperary Energy Agency is also a partner. SERVE (Sustainable Energy for Rural Village Environments) is an EU funded Concerto project which predates the HES scheme. Focused on both renewable energy and the retrofit of existing buildings, the scheme aims to upgrade 500 buildings in a section of North Tipperary over three years. The scheme was due to be launched in March, but when it emerged how closely it paralleled the planned HES scheme, the Minister brought the SERVE Project and SEI together as a means of expediting the piloting process.

Co-operation engendered a number of compromises. Tipperary Energy Agency had to drop its plan to grant aid boiler installations, while the HES scheme has adopted much of the administrative and structural work that Tipperary Energy Agency had completed ahead of the planned SERVE launch. HES is a pilot, without numeric targets, whereas SERVE aims to reduce energy usage by 40 per cent. As a result the recommendation methodology that had been developed in Tipperary was quite sophisticated. SEI’s original plan was to generate a rating along with an advisory report which said, for example; insulate your attic. Following co-operation, and input from the partners in Limerick and Clare County Councils and Limerick Clare Energy Agency, the new report builds in precise measures and delivers numerical values for the improved energy performance that will result from those measures. “Now,” says Paul Kenny, “we have an advisory report which is not perfect, but it’s something along the way.”

Margaret and Francis Murray's existing oil boiler

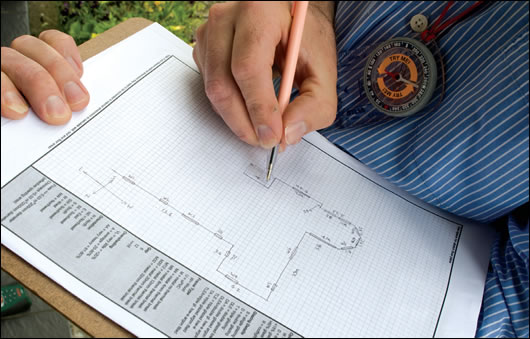

Stephen Harte drawing a map of the house: note the compass for checking orientation

“You take attic insulation. The home energy assessor goes in, sees there’s 100mm of attic insulation and it gives a U-value of say, 0.45W/m2K. Then when he goes into the advisory report, he says, upgrade it to a specific level, which is the 2008 building regs for retrofit: 0.16W/m2K for attic insulation, which is equivalent to 300mm of fibre glass. That’s a standard. So they upgrade, then go into DEAP, put in a new U-value and that will tell you that your energy use has gone from 550kWh/m2 to 450kWh/m2 …and that process is continued on down through a list.”

On site, assessor Stephen Harte begins by measuring the external envelope of the house, noting things like window orientation and over-shading. There is, he says, a lot of detective work involved in working with existing houses. “This house was probably built sometime in the 70s or early 80s, more than likely cavity block, with more than likely no insulation or 50mm insulation.”

Sometimes the owners can date the house accurately. Sometimes they can’t. You can measure window reveals to determine the thickness of the walls, and work out the construction method from that. Whether meter-boxes have been installed inside or outside also offers a clue, while differences in weathering on the roof may indicate an extension added at a later date. The meter-box itself often provides access to the cavity, assuming there is a cavity – in particular for newer homes. Access holes for cables entering and leaving the box are usually oversized, giving the assessor a view of whatever went into the cavity when the house was built. In Lorrha, Stephen Harte shines a torch down into the hole in the meter box and sees a board of loose insulation wedged behind the cable. A similar hole at the top of the box shows an empty cavity.

Margaret reveals that the house was built in 1986, and actually recalls the insulation going in. “When I saw them doing it, they were as lackadaisical, and if it fell down wrong, there it stayed. But it was Aerobord that went in, about an inch thick.” Stephen tells her it should have been installed tight against the inner leaf.

The conservatory on the southern side of the house was added in 1998. Invariably, says Paul Kenny, conservatories drag a rating down. “You can treat them as an unheated space if they’re not heated but if they’ve any connection to the main space heating system that isn’t completely separate and separately controlled, it’s part of the house, and it’s a big windowed area, so it’s a major heat loss area…You’ll probably find that they’ve got good doors, so behaviourally, they can get round it, but with DEAP, if behaviour is involved, the worst is always assumed.”

In the attic, Francis installed around 100mm of rockwool himself four or five years ago. Stephen tells him he’ll be recommending the addition of a further 200mm to bring it up to spec. “The other thing I say to people when they’re doing insulation like that is you need to check your ventilation. There’s a requirement to ventilate your attic on both sides so you get cross ventilation. This is for the timbers in the roof. On old houses, it doesn’t come into play because there’s leakiness there anyway, but if you start to make the house airtight, you have to be careful of your ventilation…I’ll be putting it down as a note on the report to make sure that it’s in line with current building regs, which is what insulation installers are supposed to do anyway.”

In the boiler house adjoining the main house, the SIME boiler isn’t one that either Stephen or Paul have encountered before. “If the boiler isn’t recorded on the database,” says Paul, “you give it a default poor value of around 65 per cent.” This is a characteristic of the DEAP methodology. If a variable cannot be determined definitively, the default value used always errs on the side of inefficiency. A house may actually have a better energy performance than the BER, but it should never be worse, assuming average behaviour patterns.

Francis Murray previously installed 100mm of attic insulation. Stephen Harte has advised him to add another 200mm

When he finishes the survey, Stephen sums things up for the Murrays. “What’s most likely going to be on the report is your attic insulation, your heating controls, your cylinder lagging jacket or factory insulated cylinder, and wall insulation. In order, attic insulation will be number one, then your wall insulation, then heating controls. You’re allowed 30 per cent of the spend to a max of e2,500, but in this case you’d be highly unlikely to spend anywhere near the maximum.”

The report, Paul adds, will also detail the non-grant aided measures that could be taken. “So for example your boiler, which would be low efficiency compared to what’s available nowadays. When your plumber is putting in controls, he could do that very cheaply because he’s already here, so you can get a good deal from him. We can’t grant aid that, but it would save 30 per cent of your oil straight away.” As part of the pilot, participating families submit oil and electricity bills to allow the agency to see what difference the measures taken have made.

In making recommendations, Paul Kenny is keen to emphasise, you go for the cheapest first. “The main things we’ll be pushing in the scheme, the most effective is attic insulation. That’s always the cheapest and the most cost effective. We prioritise in terms of low cost, high impact.” Critics have argued that the grant ceiling is too high. To get the maximum, you have to spend over e8,000. If the Murray household were to implement all the grant-aided recommendations likely to be issued to them, the cost would not come anywhere near this threshold, and theirs offers a typical case study. Is there a risk that some assessors will over-specify in order to maximise the grant? “We want to make sure we get the right quality and make sure people get value for money.” says Brian Motherway of SEI.

“We want to make sure people do the most rational things and are not spending large amounts of money to save small amounts of energy, so we want people prioritising the most rational and sensible actions and we want to maintain quality but at the same time we want to give people freedom of choice. And we don’t want to pre-guess what the assessors or what the installers are going to find when they go out to the house.” This is a pilot, he points out, and everything is done in the spirit of a pilot. Effectively, it’s about poking the market and then standing back to see what happens.

(left to right) Stephen Harte, Paul Kenny, Francis and Margaret Murray - Kenny goes through the local installer list with the Murrays

Stephen Harte checking the meter box to try to see what sort of insulation is in the cavity

“Ultimately we want to see what householders want to do in their houses; what they’re willing to pay for and what kind of grant is needed to do it, so the test is: what measures will people go for in the context of a grant, what mixture of measures might they install? Two things are likely to produce value for money. One is prioritising the most sensible actions and the second is going for a package rather than doing one thing in isolation, so the grant is set to encourage people towards a package of measures…We want to know how much will stimulate people into action because we don’t want to give away any more than is necessary from a value for money point of view. We want to make sure we’re stimulating actions, and so we expect a very healthy mix. Some people just want to do the very basic and get a small grant, and some people will want to go for bells and whistles…We want to see how people behave when you make this offer to them.”

It’s also worth noting that a number of financial products have come onto the market which offer homeowners preferential loans for investment in energy upgrades and renewables. Permanent TSB and First Active are both promoting ‘green loan’ products structured along these lines. In addition, the Green Loan home energy saver scheme, currently being piloted in Mayo, offers customised energy makeovers to qualifying householders. Approved as a cluster under SEI’s Home Energy Saving Scheme, the Mayo venture offers a range of technologies, including insulation upgrades, wood pellet stoves and solar panels at a competitive all-in-one price. In addition, as a participant in the cluster, Ulster Bank is offering finance at a variable APR of 7.7 per cent compared to their standard variable rate of 10.5 per cent.

Looking across the Home Energy Saving Scheme’s three regional pilots, Motherway says that things are going very well. “The minister only launched it in late April, but we built all the systems, we’ve recruited fifty assessors and trained them. They’re out there doing assessments on the ground and lodging assessments and advisory reports. We’ve about 1,100 individuals in the various areas that are fully live as participants and about 150 of those have had their assessments done to date. All the rules about how the assessments are done, how we lodge the systems, how we make the grant offers, they’ve all been developed and are in place, so we’ll start seeing the first grant offers going out in the next few days.”

On the ground, though the cut off point is houses constructed post-2002, Paul Kenny has seen few houses from this century. “Predominantly the people who have applied are those who think their houses are not energy efficient, so people who’ve built their houses from early 90s backwards…They’re anywhere between 1940s and 1990s. We’re seeing mainly F and G rated houses with poor heating systems, no heating controls, 100mm to 150mm of attic insulation, usually pulled back in some places and not very well laid out. Quite a few people have had their walls pumped. We are getting some people who’ve already taken action and who are now just checking how well they’ve done. Walls are either solid and can’t be upgraded, and there are some cavities that need a top up. We’re seeing a lot of double glazed windows; often houses with no cavity insulation have really nice windows…And there’s no floor insulation anywhere.”

Besides the occasional castle, stately home and 400m2 farmhouse with neither insulation nor heating, a large proportion of houses are tailor-made for the scheme. “If you take a 1997 house with 100mm cavity that usually has 40mm of insulation, you can fill the remaining 60mm using blown cavity wall insulation. The attic is always pitched, so you can get good insulation in there. You can upgrade the heating controls of the boiler relatively easily, and you can get a huge saving, you can go from an E2 or an F right down to a C2 on a house built from ‘97 onwards, or even from ‘91 onwards.”

So who decides how the work is actually done? In preparing for SERVE, Tipperary Energy Agency had decided to go further than SEI had gone with the Greener Homes scheme. SEI has drawn fire from a number of quarters because of the ease with which installers could get on the registered list. In addition to seeking tax clearance, evidence of insurance and product certification the energy agency also sought a case study, references and a safety statement from the installer. “It costs a bit of money to put a safety statement together,” says Paul Kenny, “so you’re going to weed out the fly-by-nights. And with the case study, we were really just looking for people who understood what we were trying to do and could demonstrate knowledge of their product and its quality.”

Paul Kenny of Tipperary Energy Agency is involved in managing the Tipperary pilot

Because the original SERVE project had included renewables, costings had also been sought, but these have not been published, not least because they’re subject to frequent change. “There was around a 40 per cent difference between prices, so when anyone asks me, I say shop around, even for installing attic and wall insulation. You may get the same product, but the price can vary significantly. We disclaim throughout the scheme but what we don’t have on the list is people who couldn’t be bothered spending an hour or two putting together a proper set of paper work, so that does skim off the real cowboys.”

And there will be a follow up. The first job completed by each contractor will be inspected, together with a random sample of between 20 and 30 per cent of the total number of contracts completed. “That will be checking to see that all areas are insulated and not partially. You won’t be able to check what’s been put into a wall but you will be able to check attic and heating controls. And as part of the pilot, there will be quite a bit of analysis afterwards on what the effect is per Euro spend on each of the different technologies.”

Given the speed of implementation, teething problems are inevitable. Some of the assessors are coming to grips with surveying existing houses faster than others. “We’re working through that and feedback is getting out to assessors,” says Paul Kenny, “and they’re learning…so it’s nothing that can’t be solved quickly. And this is a pilot so this is what it’s all about, trying to get that sort of thing ironed out. It’s a concern for us a little bit more than anyone else because we only have 4,000 homes in the whole region and if we get 200 done wrong, it makes our life a little more difficult in terms of reaching our targets.”

With the ‘cluster housing’ phase of the HES now rolling out nationwide, the pilot moves into a new phase. Grants of up to e2,000 per household are available to clusters of five or more houses for the range of energy improvements already specified in the regional schemes. “The objective of the cluster element” says the news release, “is to demonstrate the economies of scale that are achievable when a group of homeowners co-operate on the installation of common energy saving measures.”

John Hearne chats with Francis and Margaret Murray as Harte and Kenny continue with the energy survey

Thus far, SEI have received interest from energy agencies, residents associations, builders, landlords and management agents. “Geography is the most obvious way to build an economy of scale,” says Brian Motherway of SEI, “but we’re not limiting to that because in the spirit of the pilot we want to see what people come to us with.” The cluster phase is limited to 500 homes, and as with the regional pilots, all remedial works must be completed by that same tight deadline, November 2008. All information gathered will be evaluated to inform the potential full roll-out next year. How the scheme will look when it comes to that national roll-out remains to be seen. Paul Kenny suggests lifting the 2002 cut-off point to 2006, or even removing all house-age limits altogether. “The cheapest thing in terms of saving energy across the whole country in domestic houses is putting in attic insulation. If you were to say, just insulate every attic to 300mm, you’ll be getting the cheapest return for your Euro.”

“Because it’s a pilot, we’re testing a more complex model than you’ll see in the future.” says Brian Motherway. “You might end up saying, look I only want to go for individuals, or, I only want to go for clusters. You presumably won’t have it area based like we do now. We did learn from other schemes in terms of, is a grant programme a stimulant to action? We had a consultant analysis of different financial measures, but ultimately a lot of the measures came from the minister himself. We know that retrofitting insulation in the existing housing stock is a major priority. The question is how to get the best value for money with the maximal uptake. The kinds of methods we’re testing now are the ones that we think will do that. First of all, you make it nice and simple: These are the kinds of measures we’ll support, these are the grant levels, we’ll link it to the BER so you‘ll know exactly what you’re in for, this is my rating now, this is my rating afterwards, this is how much money I can expect to save if I take these actions…Then we’re testing specific actions like the economies of scale. All of that will be fed back into government to ultimately decide what to do next.”

- Articles

- renewable energy

- Measured efforts

- sei

- sustainable

- energy

- Ireland

- refurbishment

- home energy saving scheme

- North Tipperary

- DEAP

- Pilot Scheme

Related items

-

Embody language

Embody language -

Peaky blinder

Peaky blinder -

History repeating

History repeating -

King of the castle

King of the castle -

Energy poverty and electric heating

Energy poverty and electric heating -

Build Homes Better updates Isoquick certification to tackle brick support challenge

Build Homes Better updates Isoquick certification to tackle brick support challenge -

Flat earth

Flat earth -

Material matters - A palette for a vulnerable planet

Material matters - A palette for a vulnerable planet -

Derelict to dream home

Derelict to dream home -

Final opportunity for construction professionals to secure 80 per cent training subsidies

Final opportunity for construction professionals to secure 80 per cent training subsidies -

Big picture - Points of access to resilient living

Big picture - Points of access to resilient living -

Storm breaker

Storm breaker