- Retrofit

- Posted

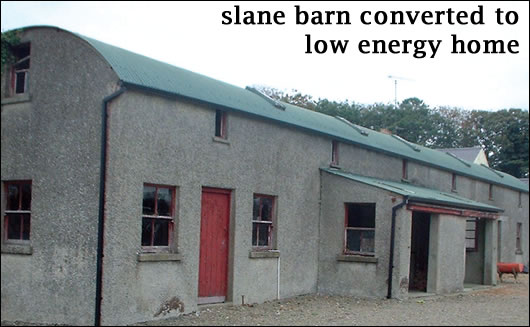

Slane barn retrofit

An old agricultural barn in rural Meath posed architect Fergal McGirl with an interesting challenge: how to upgrade it into a modern house while maintaining its original aesthetic. Lenny Antonelli reports on a home that marries its traditional look with modern green features such as triple-glazed windows and a ground-source heat pump.

If someone suggested the idea of living in a barn, you probably wouldn’t be too keen. But when Everina Kilfeather and her husband started thinking about upgrading their farmhouse in Gilltown, County Meath, they realised they’d need somewhere to live during the refurbishment – they decided to renovate an old barn on the site and live there while they set about tackling the main house.

The couple hired architect Fergal McGirl to design the project – McGirl wrote about the energy upgrade of historic buildings in Construct Ireland last year (issue 9, volume 4), and is developing a specialisation in energy upgrades to older buildings. He says the mass concrete formwork barn is about 80 or 90 years old – it was used as a hay shed and to store machinery before the upgrade.

“The most important thing we wanted to do was to keep the barn as it was,” says Kilfeather, who trains horses on the site. “We didn’t want to knock any of the external walls – and in actual fact it would have been easier for the builder to knock it. And we wanted loads of light, and to have geothermal energy and be as energy efficient as possible.”

From the outset McGirl felt the building should not compete with the main house architecturally, and that a “low-key approach to the design interventions” was warranted. Initial discussions with the planners at Meath County Council about the designs were positive, and planning permission was granted in the summer of 2006.

McGirl set about upgrading the walls, and installed 75mm of Xtratherm composite insulating board internally. The insulation is continuous, running up through the first floor to mitigate thermal bridging at the junction between the wall and floor. Existing steel floor beams that span the width of the building were retained and timber joisting was reinstated between the beams. As the timber joists therefore ran parallel to the main external walls of the building, this facilitated the continuation of the internal insulation vertically through the floor zone along the external walls – an area often overlooked when retrofitting internal insulation, leading to a cold bridge along the floor zone. The insulation lining was sealed at all relevant junctions to reduce the risk of air movement behind the lining board and reduce the risk of interstitial condensation too.

McGirl acknowledges there has been significant research into approaches to internal insulation since the works were undertaken (particularly by the architect Joseph Little, with whom he now shares office space in Dublin, and whose research has been published extensively in Construct Ireland over the past year). “The specification may be approached differently today,” McGirl says.

The early 20th century barn was overhauled and finished with a new sand and cement pebble-dash render, maintaining its traditional exterior while significantly freshening up the original look of the barn which was used as a hay shed and to store machinery before the upgrade

He wouldn’t have insulated the barn externally though. Because the site is a working farm, he’d be concerned about the vulnerability of a mineral-based external insulation to achieve the agricultural-style finish that was required. “As there turned out to be effectively no foundations under the existing mass concrete walls, it may have been problematic achieving an acceptable thermal bridging detail at the ground floor to external wall junction,” McGirl adds. “The considerable thermal mass of the 550mm thick mass concrete walls would also have delayed the response time of the heating system.”

Although he says the design was “not approached as a showcase sustainable project”, the building boasts some interesting green features. McGirl chose to insulate between the roof joists with 140mm of Holzflex, a semi-rigid wood fibre insulation from Ecological Building Systems. Wood chips are the main raw material used to produce Holzflex – it has a thermal conductivity of 0.38 W/mK according to the company. Counter-battening and a further 60mm of Holzflex was installed below this, followed by an Intello Plus vapour barrier – also from Ecological Building Systems – and 12mm of plasterboard beneath. The membrane was sealed at joints and lapped onto external walls and sealed to the underside of the roof structure.

Intello acts as both an air barrier and an “intelligent” vapour check according to Ecological Building Systems. In the winter it prevents vapour from getting in, but in summer it becomes up to fifty times more vapour permeable to allow it to diffuse out. It’s designed to allow building components to dry out rapidly if moisture penetrates the building envelope.

The roof level was raised slightly above its original line to ensure ample headroom at first floor level. The curved profile of the roof was achieved with preformed curved steel beams at 2.5m centres bridged with timber joists. “The barrel vaulted form creates a pleasant series of internal spaces at first floor level that echo the former use of the building,” McGirl says.

The house overlooks an orchard to the south and west, with full-height glazing merging the inside and out and letting plenty of natural light in

Downstairs, the existing concrete floor was removed, and a 75mm screed installed over an underfloor heating system laid on top of 100mm of Kingspan Thermafloor TF70 insulation, which forms a continuous thermal lining with the internal insulation. Underfloor heating features upstairs too, with heating pipes built into a liquid screed on plywood deck. McGirl chose to heat the house with a ground-source heat pump, a 14.2kw Alpha-Innotec unit with a horizontal collector – the system was designed to be large enough to heat the main farmhouse in future too. The collector is located in a working paddock, with no loss of usable space on the farm.

Kilfeather is a big fan of the heat pump. "I find it fabulous, it's just so clean. You pay one electricity bill every two months,” she says. “You don't have to worry about oil going down or anything like that. In the other house we were spending a fortune on immersions and oil." u

Triple-glazed Markfönster Thermix windows were chosen for the barn. Supplied in Ireland by the Cork-based Swedish Trade Centre, the Swedish pine windows feature two low-e coatings and argon fill. The glazing boasts a U-value of 0.68 W/m2K, with the overall units including frame coming in at 1.0 W/m2K – a performance that can be boosted to 0.9 W/m2K if aluminium cladding is used. Markfönster was founded in Sweden in 1950 – the company uses timber from the freezing cold north of Sweden, which it says produces particularly dense timber.

The largest glazed sections face south-west over an orchard – there is much less glazing on the north elevation. McGirl retained all the original window opes – something Kilfeather was keen on – as well as the original steel support beams. His original idea was to create a double-height ‘winter garden’ built into the existing envelope of the barn and looking out on to the orchard, but this was modified into the double-height glazed atrium that now sits at the core of the building overlooking the orchard. “When the sun shines it’s fabulous,” Kilfeather says.

The downstairs, at 169 square metres, features the light-infused main living areas – as well as utility spaces

McGirl adds: “A double-height window framed by the access bridge opens the atrium towards the orchard. The stairs were suppressed behind a storey-and-a-half feature wall to contain the living room space.” High level clerestory glazing from the east façade ensures that this central space of the house is brightly lit throughout the day.

The building forms the divider between the orchard to the west – which sits between the barn and the main house – and a paddock to the east. Visitors enter the barn through a single storey entrance on the east side, which leads to the expansive view of the orchard in the atrium. Downstairs there’s a living room, office and kitchen-cum-dining room, while upstairs there’s three bedrooms – including one en suite – and a bathroom. The ground floor is 169 square metres including utility spaces, the first floor is 119 square metres.

The exterior may be quite traditional, but the design of the interior is throughly modern

Outside, the old render was removed and a new sand and cement pebble-dash render applied to freshen up the exterior while maintaining its traditional finish. The overall design is certainly impressive: a rural dwelling that – unlike many – fits snuggly in the countryside with its very traditional exterior, but with a thoroughly contemporary design inside. “The external finishes, which may be unconventional for a domestic project, were specified to integrate the building into its rural context,” McGirl says. u

The roof was finished with a Tegral Fineline 19 profiled metal roof with a ventilated battened cavity. A green colour was selected to match the original roof of the building. McGirl says that with powder-coated fascias and soffits, the render finish and dark timber stained windows, the house will require “practically no external maintenance.”

The house boasts triple-glazed Markfonster windows with an overall Uvalue of 1.0 W/m2K

The couple have been living in the house for two years now. Everina Kilfeather says that the main farmhouse was a “gas guzzler”. They were paying €7,000 a year on oil there, but their overall energy bills – for lighting, heating and domestic hot water for the whole barn, which includes offices too – are never more than €300 a month during the coldest periods. They’re now getting around to tackling the main house – which was built in the 1820s – and plan to extend it and replace the roof.

Detached housing in the countryside often means throwing up ugly and jarring new housing with little attention to environmental performance, but the Kilfeathers’ upgrade not only boasts some commendable green features, it has revitalised an old barn and turned it into a modern family home that fits snuggly in its rural setting.

Selected project details

Client: Everina & Johnny Kilfeather

Architect: Fergal McGirl

Building contractor: Michael Hughes & Associates

Insulation: Ecological Building Systems , Kingspan , Xtratherm

Triple-glazed windows: Swedish Trade Centre

Heat Pump: Powertech

- Articles

- retrofit

- Slane barn retrofit

- triple glaze windows

- ground source heat pump

- geothermal energy

- composite insulating board

- Holzflex

- Thermafloor

- Kingspan

Related items

-

Peaky blinder

Peaky blinder -

History repeating

History repeating -

Retrofit redux: Catching up with A3

-

The transformative power of industrialised retrofit

-

Derelict to dream home

Derelict to dream home -

Traditional homes retrofit grant pilot launched

-

Dr. Barry Mc Carron appointed MD of KORE Retrofit

Dr. Barry Mc Carron appointed MD of KORE Retrofit -

Bungalow Bills

Bungalow Bills -

New scheme offers up to €75,000 retrofit loans at low cost

-

Phit the bill

Phit the bill -

Mainstreaming retrofit – a massive missed opportunity

-

It's a lovely house to live in now

It's a lovely house to live in now