Renewed efforts

In the future, the high cost and scarcity of fossil energy may force a shift towards retaining and modernising old buildings, thereby avoiding the use of huge amounts of energy to manufacture building materials. John Hearne visited the Belvedere Orphanage, a group of 19th century dwellings whose low energy refurbishment may offer a template for development in the future, by using wood pellet district heating and a host of energy saving measures whilst nonetheless paying great attention to preserving the buildings’ heritage value.

The challenges thrown up by architectural conservation can be daunting on their own. Add in a sustainability agenda, all kinds of budgetary constraints and the ultimate goal of creating a workable social housing project and those challenges can seem insurmountable. But in a major new project in Tyrrelspass, Westmeath County Council has managed to incorporate one of the country’s first wood pellet district heating systems into a beautifully restored nineteenth century orphanage.

“Unlike most formal institutions of the period, the orphanage comprised six individual structures.” architect Lenzie O’Sullivan of de Blacam & Meagher explains. “According to Slater’s Directory of 1856, the institute was designed to accommodate widows and their children. It’s built in the Tudor Revival style of the early 19th century, along a carefully set out symmetrical crescent facing communal parkland. The layout mirrors the configuration of the adjacent 19th century village green in Tyrrelspass, also instigated by Jane, Countess of Belvedere.” Four identical cottages are book-ended by a parochial school to the South and the large matron’s house to the North. Deceptively large, they incorporate a front to rear split level structure with four separate levels within each cottage. All contain three well-proportioned rooms and a small bedroom off the front room, with a cellar underneath. “It was a very clever design at the time.” says Ciaran Jordan of Westmeath County Council. “They were attempting, rather than build a huge, old institution, to instead make it look like a town and make it feel like a town.” After the orphanage closed in the 1940s, the buildings fell into disrepair. By the time the county council acquired the site in the eighties, most were in an advanced state of dilapidation, with one of the buildings completely destroyed and trees actually growing up through foundations. Several possibilities were discussed before the local authority settled on a plan for the site. As Ciaran Jordan explains, the Belvedere project was not the most cost effective means of meeting local housing needs. “Without the Department of the Environment on board, their housing project unit, we wouldn’t have been able to do it…We dabbled with the idea of letting it go into private development but that wasn’t economically viable. We decided the only use we could think of, particularly that was compatible with its history, was social housing.” The project also received funding under SEI’s House of Tomorrow programme.

In practise, the twin aims of conservation and sustainability didn’t conflict quite as much as might have been expected. “A lot of it was rebuilding.” says Lenzie O’Sullivan. “We had the skeleton of a building, and that was about it, so there was an opportunity to conceal anything that might have been obstructive. The more dilapidated, the easier it is to conceal.” Much of the building fabric of the cottages; original timber, windows, internal plastering and fireplaces were either missing or beyond meaningful repair. The matron’s house at the end of the crescent however had been in continuous use throughout its life, and much remained here to provide the restoration team with reference details. Original windows, rainwater goods, some internal plastering and the ornate hardwood bargeboards were pretty much as they had been a hundred and fifty years before. Most of the cottages retained their original rubble-walls and it was here that energy reduction met its first obstacle. “From an energy standpoint there were particular difficulties in trying to make this a low energy project.” says building services engineer, Paraic Davis of Davis Associates. “The brief from the local authority was that the energy consumption should be as low as possible in the buildings. Because we didn’t want to interfere with the visible fabric of the building, it meant that it wasn’t possible to use, for example, double glazing to the front of the buildings, nor was it possible to insulate the walls either front or back, because of the kind of construction they were, which was a mix of rubble wall and cut stone.”

In order to retain the original look of the building, the diamond-lattice windows to the front had to be made to order. “It was a question that the council posed.” says Lenzie O’Sullivan. “Could we make those windows double glazed? But whatever way we tried it, it didn’t work…It just looked terrible. You can’t do lattice frame windows with double glazing. We inspected versions of it that had been done before, but because they’re 16mm thick, they’re huge and chunky, it looks like you have a steel door instead of a window…It looks awful.” Compromise came through the installation of high-grade double glazing to the back, while the historically faithful, if thermally deficient units went into the front. Similarly, because the original walls couldn’t be insulated to modern standards, the design team chose instead to beef up the insulation spec underfoot and overhead. The floors are insulated with 150mm of Kooltherm K3 insulation with a vertical strip of K3 to the perimeter of the floor slab. The roofs are insulated with 120mm Therma Pitch 10 Roof Insulation while the walls/pitched roof junction is lined with low-E reflective quilt insulation. “The buildings are stepped so behind a lot of the walls into the living room and the kitchen, there’s just soil, so they had to be dry lined from the inside.” O’Sullivan explains. “From a conservation point of view, that wasn’t ideal. We would have preferred to put the insulation on the outside of the building, but the basic structural implications of digging big holes beside old buildings made it too risky.”

Paraic Davis points out that while conservation imperatives meant that the original walls had to be kept free of modern insulation, traditional methods had some inherent thermal advantages. “Bear in mind that rubble wall construction with lime plaster gives a reasonable U value because lime does have reasonable insulation properties, and so a traditional rubble wall construction with lime plaster on either side would have a far better insulation value than a modern concrete wall.” Lenzie O’Sullivan agrees. “Lime is breathable in that moisture can come in and out of it…We had 30mm of lime render on the outside and about 25mm to 30mm on the inside. The density of it, and the volume of it per square foot, seals the building. There’s more of a thermal quality to lime render than there is to a cement render or a gypsum render…And lime render, it’s great because it’s flexible. If there’s any movement in the building, the lime render will move with it, so cracking will be reduced, and those kinds of walls should be able to breathe, in other words the moisture should be able to go over and back through it, depending on the pressure outside.”

When it came to sourcing materials, again, it was a matter of balancing budgetary, conservation and sustainability requirements. The advanced state of disrepair, together with decades of pillaging meant that original features and materials were in short supply. The custom-made lattice windows were sourced locally, while the matron’s house was re-roofed using all of the tiles recovered onsite. Blue Bangor slates, similar in tone to the originals, were sourced to roof the rest of the cottages.

Architect Lenzie O’Sullivan explains that the team ran into a central conservation issue early in the project. “One of the main issues was the rebuilding of the missing house. It could, in certain conservation circles, have been argued that what we’ve done is pastiche in that we’ve rebuilt it entirely, but we argued that that building was part of a sequence of buildings. Because it wasn’t there – all that was left was the foundations – the whole scheme ceased to work properly and the intention of having a crescent was gone. The crescent shape was very important because the designer of the Belvedere Orphanage was also the instigator of the village green in Tyrrelspass, which follows the same shape.”

When it came to choosing a heat source for the development, engineer Paraic Davis says the local authority provided the company with a simple brief. “We compared wood pellet with oil boilers, geothermal heat-pump, wood fuel boilers and LPG. We considered them in terms of capital cost, running costs, plant space, fuel storage, reliability, maintenance and vulnerability to user interference and we concluded that the wood pellet was the most appropriate system under those headings. It wasn’t about any green conscience. In ten years time it will have cost the local authority less, significantly less to run this system…Environmental considerations were a starting point but the brief to us from the local authority was this has to stack up financially. We added up the ten year costs, and the wood pellet system was the one that was going to be least expensive over that period. It has a high capital cost but very low running costs. Fuel costs will remain stable and it’s impervious to user interference.”

The boiler house, adjacent to the matron’s house, was built in a wedge shape in order to present the least façade and slot neatly into the crescent formation. Heavily screened by established hedging and finished like the cottages in a lime render, the machinery inside is almost completely silent from the road. The boiler itself sits just inside the door, and is fed from an 18 tonne pellet silo which takes up two thirds of the internal space. The boiler, an 80kW Austrian KWB was supplied, installed and commissioned by Natural Power Supply in Waterford.

“The gathering device in the base of the silo collects the pellets and brings them to an augur which delivers them on demand to the boiler.” Hugh Foley of mechanical contractor Ross Technical Services in Dungarvan explains. “The store is fully insulated and dry-lined. It’s important to keep the fuel dry and the boiler itself, despite the pipe-work being insulated, has a certain level of heat leakage which helps to maintain the dryness of the building.” Eddie Moran, area supervisor with the county council confirms that the machinery requires very little maintenance and has given no real trouble since installation. “It’s on constant standby and will kick in as required. The local area officer looks after the maintenance of it, and it’s de-ashed every few weeks.” It produces very little ash. A year’s worth, spread beneath the trees which screen the boiler house, is barely noticeable.

The real innovation in the development is of course the district heating system. “The primary reason for going district was the efficiency it gives.” says Paraic Davis. “A large boiler serving multiple loads can run much more efficiently than small individual boilers. This was the reason for putting in a centralised heating boiler, fed on wood pellets, then distributing the heat using district heating pipe-work.” The fact that the system would service an existing suite of buildings did present particular challenges. “We were trying to interfere with the buildings to as small a degree as possible. District heating pipe-work has quite a large diameter and it’s not very flexible, and so bringing the pipe-work in underground and bringing it up into each house for connection to a metre and distribution throughout the house, that posed quite a challenge. It required careful coordination between the mechanical contractor and the builder. There had to be a certain degree of flexibility and each house had to be treated individually depending on where the pipe-work originated out on the street.” The fact that the buildings were quite close together and arrayed in a crescent facilitated the network to a degree; the denser the development, the more feasible a district heating system. As it stands, heat loss between the boiler and the last house on the spine is in the order of 2 to 3 per cent. “It’s at an acceptable level.” says Davis. “Prior to doing the design, we did a feasibility study for Westmeath County Council on both the boiler and the pipe-work. Typically in district heating systems, the pipe-work determines whether it’s viable or not. The pipe-work is determined by the layout of the houses, so anyone considering district heating should look at the layout of their buildings and try to group them as close together as possible, or group them so that pipe-work is minimised.” Because of the highly engineered materials and labour involved, district heating piping is costly. “The installation cost of the pipe-work is high. Each joint takes two men twenty minutes to make. That’s a lot of labour, so if you can minimise the joints, if you can minimise the pipe-work you can save a lot of money.”

The pipe-work itself was provided by Noel Walshe the Irish agent for Logstor. He says that the unique element of the installation lies in the fact that flow and return pipes were housed together in a single jacket. “This reduces heat loss by a third,” he explains, “because there’s a smaller surface area on the outside…The two pipes run down by the side of the building, then there are connections into each of the individual houses. The connections into the houses are double piped as well, so it was a complete double pipe system, and in addition to reducing heat loss, it also cuts down on labour costs because the trench only has to be the width of a single pipe.” One pipe sits on top of the other. Both are then covered in a black poly-ethylene jacket, then insulated with polyurethane. “The question you get is, what with the pipes being so close together, won’t heat just travel from one pipe to another? But they’ve done all kinds of investigations on that, and the amount of heat that’s transferred is quite negligible. In Tyrrelspass, they used Pecs piping. It’s cross linked poly-ethylene with an oxygen diffusion barrier to prevent corrosion.”

“All in all,” Walshe concludes, “this was one of the best systems you could conceive. I would challenge anyone to sit down and come up with something better.”

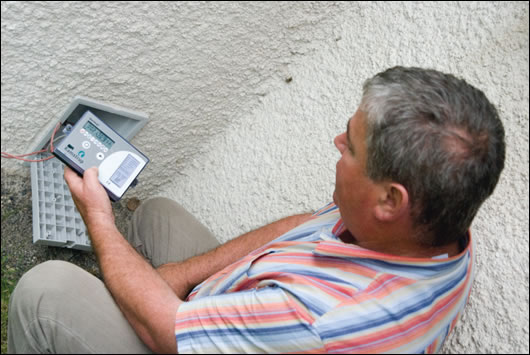

The next question was how to distribute the heat inside the house. “We looked at radiators and underfloor,” says Paraic Davis, “and eventually concluded, both from a user comfort point of view and from an energy efficiency point of view, underfloor heating both in ground floor and first floor is the way to go. In the ground floor we have a solid screed and upstairs we have suspended timber floors, and so the installation methods were different for each. Upstairs, we used a system whereby the pipe-work is laid in aluminium trays which sit between the joists and the heat is conducted to the floorboards by the aluminium tray which is also in contact with the pipes.” The Myson underfloor heating system was also installed by mechanical contractors Ross Technical Services. The controls, built by OJ Electronics in Denmark and wall-mounted in the kitchen of each of the cottages, provide for a zone on each floor.

With the development fully occupied for the past year, the tenants are largely happy with their innovative heating system. “It’s lovely, they’ve done a lovely job.” says Eileen Hyland in Number 5. “I find it great. It’s very roomy and the heat is terrific.” There have been problems however. Many of the residents have struggled with the fact that underfloor doesn’t provide heating on demand. To get the most out of it, you’ve got to plan usage and programme the system to deliver accordingly. “It takes a few hours to heat up if it went down cold.” says Hyland. “If someone comes in, sometimes someone will ring and say can I come down for the chat? And you’d say come on, and you’d hate them to be sitting in the cold. But it takes a couple of hours to heat up, and by then they’d be gone.” Angela Kelly in Number 7 is also delighted with her new house. “It’s lovely, I love it here, it’s ever so cosy. The underfloor is grand, I haven’t any complaints about the house at all. I can feel it warm underfoot and that’s just great.” Since the installers pre-programmed the system using the wall-mounted control, she has been happy to run with that plan and leaves the system alone. Both women keep electric heaters on stand-by though neither report using them over the past twelve months.

The county council confirm that there have been teething issues. “Some of the houses would have been using a lot of heat originally.” says Eddie Moran, “until we came back and said look, you don’t need this, so we pushed it back down, we put them on a different program. Some of them would have had it running continually.” While all of the houses have individual heat metres installed behind an external hatch, the local authority has not yet begun to charge tenants. “In the first year we set them up on a nominal charge per week.” Moran continues “and our proposal is, after the first year and the drying process and all of that, that we’d look at billing through metre. By the new year, it’ll be on a metre system and they’ll be billed for what they use and that should curtail usage.” The wall-mounted controls do provide a high degree of controllability, but evidence suggests they are not as user friendly as they might be. Hugh Foley of Ross Technical Services contends that while that they are easy to understand, these controls were particularly chosen because they are ‘fit and forget’ units. “Literally all they have to do is leave them alone. If they leave them alone, most people are happy…A lot of people have this fear of digital read-outs, once it looks computery, they tend to freeze. We have to overcome that. We’ve done dozens of houses, we’ve met accountants, very successful business people, college academics and a proportion of those look at this and go, I won’t be able to understand it…Some people just have a technology aversion.” Between the controls issue and the fact that underfloor doesn’t provide heat on demand, the county-council admits that energy usage figures have fluctuated wildly in the first year. “A lot of people were finding that the houses were too hot or difficult to control.” says Eddie Moran. “It was all to do with learning how to use them. It’s probably taken up to the last couple of months to understand how the controls work…They’re far better now than they were originally. It was more that they were looking for instant heat. They had to realise that they had to wait for it.”

Ciaran Jordan says that running a district heating system as a local authority landlord does confer a wider range duties than would be the case if the tenants looked after heating themselves. “In an ideal world, we could have put in individual metres and a card system but it would have involved considerable additional costs; it wasn’t worth it. The scheme as it is at the moment is working, it’s relatively painless, it involves a little bit more but we think it’s worth it. So far so good. There’s nothing here to tell you that this is a local authority scheme.” He says that in any and all future residential developments, the local authority will assess the sustainable options that are available to them. But judged against either aesthetic or sustainable criteria, they’ll be hard pressed to top this one.

Selected project team members:

Client: Westmeath County Council

Architect: de Blacam and Meagher

M & E engineers: David Associates

Main contractor: Oliver Donlon Developments

Mechanical contractor: Ross Technical Services

- Articles

- Sustainable Building Technology

- Renewed Efforts

- belvedere orphanage

- wood pellet

- district heating

- kooltherm

- Logstor

Related items

-

New heat pumps and pellet stoves from Waterford Stanley

New heat pumps and pellet stoves from Waterford Stanley -

Kingspan launches new lower lambda Kooltherm range

Kingspan launches new lower lambda Kooltherm range -

District heating and passive house - are they compatible?

District heating and passive house - are they compatible? -

Affordable passive scheme that beggars belief

Affordable passive scheme that beggars belief -

Opinion

-

Thermal bridging

-

Isover awards

-

Carlow A1 upgrade

-

Zero waste

-

Clonakilty eco house

-

Cutting oil dependecy

-

Oil Leak