- Water

- Posted

The state of water in Ireland

Jeff Colley: Regarding the drinking water report, where do the quality deficiencies lie in drinking water supply?

Matt Crowe: The key findings of the drinking water report were that in general water supplied by sanitary authorities, is of a satisfactory nature, and that water supplied by group water schemes is generally unsatisfactory. So the deficiency in drinking water is mainly in the group water supply area.

JC: What would you say the main issues are for group water schemes; what are the main problems?

MC: The issue with group schemes is first of all that there’s a very large number of them. There are in the region of 5,500 group schemes in Ireland, mainly in the western counties. They provide water to a relatively small number of consumers per scheme, so the average size of a group water scheme is much smaller than a public water supply. Many group supplies do not have any treatment of the water prior to distribution, so the water in many cases is not disinfected. The key indicator for drinking water quality, in relation to risk to public health, is faecal coliforms. What we find is that the overall compliance rate for faecal coliforms in group schemes is still considerably below that for public supplies. In group schemes that have disinfection, we should certainly find that the compliance rate for faecal coliforms improves considerably.

What we found in 2002, which we were not in a position to report on in previous years, is that within the group sector, the quality deficiency mainly resides in what we term the private group schemes. These are the group schemes which are responsible for both abstraction and distribution of their water. By and large the group schemes that get their water from a public supply have a similar quality of drinking water to the public supplies themselves. So this narrows down the problem to a smaller number of specific types of group schemes.

JC: What responsibilities do local authorities have with regard to private and part-private group water schemes?

MC: . The main responsibility of the local authority is that, if they become aware of a problem in a group scheme, they must provide assistance to the group scheme, in relation to what steps need to be taken to bring the water back to a suitable quality. Under the new Drinking Water Regulations (S.I. 439 of 2000) which came into force in January 2004, provision has been made for offences and penalties in the case of private water suppliers which fail to comply with a notice served by a sanitary authority.

JC: As you have said, generally the standard for public water schemes tends to be much better, but there are certain issues, and there is a low percentage of schemes which are not satisfactory.

MC: Indeed there are. What we are drawing attention to in our report, in relation to the public supplies, is that while the overall quality of water supplied by public schemes is satisfactory, there are a number of plants throughout the country which repeatedly breach specific standards for drinking water, and we want the local authorities to identify those plants and to prepare and implement corrective action plans for the plants, so that the drinking water that is supplied by them is in compliance with the standards.

JC: Are there penalties or repercussions relating to drinking water supply?

MC: For public water supplies there are not. For private water schemes, a new licensing system is planned and private schemes will require a licence from the local authority. The new Drinking Water Regulations (S.I. 439 of 2000) which came into force in January 2004, make provision for offences and penalties in the case of private water suppliers which fail to comply with a notice served by a sanitary authority.

JC: The report also calls for an urgent risk assessment for Cryptospiridium in every local authority supply. What threat does Cryptospiridium pose?

MC: Cryptospiridium is a protazoa, a paracite, and certain parts of the population are more at risk from cryptospiridium than others, particularly the young and the old, and those with a weakened immune system. It is very serious and an outbreak of cryptospiridium can have very serious consequences for the consumers of the water. The sources or causes of Cryptospiridium include cattle or grazing animals, when allowed to graze close to the source of a water supply. That is why it is important that the sources of water supplies be properly protected, and buffer zones be provided around water supplies. It is particularly a potential problem in water supplies that get their water from a surface water source, like a river or a lake, where there might be agricultural runoff or grazing animals in the vicinity.

JC: In the report you also call for widespread monitoring of Cryptospiridium.

MC: What we are calling for is that local authorities do a risk assessment of the likelihood of their being a problem with cryptospiridium in their supplies, and that following the conduct of such a risk assessment that, if monitoring is needed, it should be carried out.

JC: What actions can the OEE take regarding local authorities and drinking water quality?

MC: The OEE audits local authorities in relation to the management and operation of drinking water plants. We will be stepping up the level of audits of local authorities this year. We are planning to audit all local authorities during 2004, and one of the things we will be doing when we audit local authorities is to check to see if compliance action plans have been put in place for plants that are persistently in breach of the standards.

JC: Where does it go next if a local authority is found to be consistently in breach?

MC: The powers that we have in relation to local authorities are to do with dealing with situations where there is a risk of environmental pollution being caused. For instance, if a drinking water plant, as a result of poor management, is causing environmental pollution, by discharging sludge into a river, then we can use our powers to deal with that type of an issue.

Sanitary authorities or private suppliers of water do not deliberately produce poor quality drinking water. So there will usually be a reason why a plant is not operating properly, and it might be that increased capital investment is needed, for instance. The bottom line is that we cannot prosecute a local authority if they’re not meeting the drinking water standards.

THE URBAN WASTE WATER REPORT

JC: Having studied the performance of urban waste water treatment plants throughout the country what are the main findings?

MC: First of all, the number of secondary wastewater treatment plants in the country is increasing. This is because of the fact that Ireland is implementing the Urban Wastewater Directive, which requires that all large cities and towns throughout the country will need secondary wastewater treatment. There is a lot of investment going into the construction of secondary wastewater treatment plants around the country. What we have found is thatlarger more modern plants are outperforming smaller and older plants. In common with the situation with drinking water, what we are urging local authorities to do is to develop and implement corrective action plans for secondary wastewater treatment plants under their control which are consistently in breach of the standards.

JC: Typically, where do the main problems in urban waste water treatment arise from? Is the poor performance of small plants, which only process relatively low volumes of waste water, an issue?

MC: Even for smaller plants, if they are discharging effluent that is not meeting the standards they could have a very significant impact on the waters to which they discharge. So we certainly would consider poor performance of any wastewater treatment plant as a relatively serious matter. We are also asking local authorities to look particularly at plants where there is a demonstrably negative impact on the waters to which they discharge and to take urgent corrective action in relation to them.

There is a recommendations section in the Urban Wastewater Report which lists recommendations which are mainly aimed at local authorities, but something that we want to see local authorities do is develop a management systems approach to the management and operation of urban wastewater plants under their control. Similarly, in line with the drinking water situation, we will be conducting audits of local authorities, and one of the things we will be looking at when we do our audits, is to see whether or not corrective action plans are in place for plants that are consistently in breach of the standards, and also whether or not local authorities are developing management systems for the operation and management of their plants.

JC: What actions can the OEE take when plants are consistently in breach?

MC: For urban wastewater plants that are consistently in breach of the standards, the OEE will consider the use of its enforcement powers, where the breaching of standards is resulting in environmental pollution in the waters to which the effluent is discharged.

JC: Nearly two thirds of the 114 plants subject to the Urban Waste Water Treatment Regulations, 2001, failed to comply with one or more of the standards during the reporting period. Are there many urban waste water treatment plants that are not subject to these regulations?

MC: No, there are not. All plants that serve a population greater than 2,000 are subject to the regulations, but any plant, regardless of its size, that is causing environmental pollution, is potentially problematic, and would be subject to the scrutiny of the OEE.

The OEE stress that the high level of non-compliance, regarding Urban Waste Water Treatment Regulations, is unacceptable and local authorities need to address non-compliance with the standards as a matter of urgency.

JC: What are the potential consequences for local authorities who fail to address this issue?

MC: The EPA will certainly consider the use of its enforcement powers, up to and including prosecution, where urban wastewater treatment plants are consistently in breach of the standards and are causing environmental pollution.

JC: The report highlights problems with regard to the quality of sludge produced in treatment plants, 45% of which was reported to be reused in agriculture. Why, in many cases, is an unsatisfactory quality of sludge being reused?

MC: It is not that there is necessarily an unsatisfactory quality of sludge being reused. What we are drawing attention to here is the absence of proper procedures being in place for managing and controlling the use of sewage sludge in agriculture. There is a specific set of regulations which govern the steps that need to be taken where sewage sludge is to be used in agriculture. In some local authority areas, the procedures in relation to this are not apparent in the conduct of the audits that we are doing. We are drawing attention to this, and recommending that local authorities put the procedures in place and ensure that all the proper steps are being taken in relation to the use of sewage sludge in agriculture.

The Phosphorous Regulations Report

JC: What are the main problems that the Phosphorous Regulations are intended to deal with?

MC: The Phosphorous regulations were introduced to tackle the problem of eutrophication in Ireland’s rivers and lakes. Over the past 20 years or so there has been a gradual decline in the overall quality of rivers and lakes in Ireland, mainly due to the over-enrichment of waters by nutrients such as phosphorous. The specific objective of the Phosphorous Regulations is to reverse this trend in decline in water quality and bring about an improvement in the quality of rivers and lakes in Ireland. The targets that are set in these regulations are to be met by 2007, and they are interim targets, in the sense that, under the Water Framework Directive, all waters in Ireland will be required to achieve a satisfactory or good quality status by 2015. The Phosphorous Regulations should really be considered as a step along the way to meeting the longer term requirements of the Water Framework Directive.

JC: What are the main causes of eutrophication in water, and what are the potential problems eutrophication poses for the environment in Ireland?

MC: The main causes of eutrophication are activities which might give rise to the introduction of nutrients to waters, and these would include poorly operated urban wastewater treatment plants, poorly operated septic tanks and other small scale wastewater treatment systems, agricultural runoff, either directly from farmyards or through the diffuse movement of nutrients through soils into waters.

The main consequence of eutrophication is that it changes the ecological balance of the water concerned and results in the growth of certain types of species within the system which in turn result in a reduction in oxygen levels in the water, which have an effect on both plant and animal species which are dependent on oxygen.

JC: With 38.2% of river stations monitored not currently in compliance with the targets laid down by the regulations, what actions need to be taken to bring this standard up?

MC: The report covers how local authorities are doing, in implementing their responsibilities under the Phosphorous Regulations. So the report summarises the various steps and measures that are being taken by local authorities, and presents specific information then for each individual local authority area. There are a wide range of measures required in order to improve water quality in Ireland.

Action has to be taken under each of the many categories we have identified in order to improve water quality. There is an integrated catchment management approach required, in order to deal with the pressures on waters that are causing the problem, and reducing those pressures so that the problem begins to disappear.

JC: How many lakes fail to comply with the targets?

MC: There is information available on 238 lakes, 152 of which currently comply, while the remaining 86 do not. There has been a reduction in the number of high quality river stations throughout the country. The Phosphorous Regulations require both the protection of waters that are of satisfactory quality and the improvement of waters that are of unsatisfactory quality. Since the regulations were introduced we have seen a reduction in the number of the highest quality stations and we are particularly concerned about that, because these are the pristine areas of rivers and they need to be protected. We are urging local authorities to identify what the problem is, specifically in these areas, and address that as a matter of urgency to ensure there is no further deterioration or reduction in the numbers, and to try and reverse whatever deterioration has happened since the regulations came in.

JC: The report also mentions that local authorities are frequently encountering problems with single house treatment systems. What actions would you recommend local authorities, home owners, builders and so on take to improve this situation?

MC: The EPA has issued guidance on this. We have published guidance on single house treatment systems, which covers the design, operation and maintenance of these systems, including septic tanks, and other types of single house treatment systems.

We have also been engaged with FAS and the Geological Survey of Ireland in the development of a training programme for local authority staff and other professionals in the conduct of site assessments prior to deciding whether or not a site is suitable for a septic tank or for another type of onsite treatment system. This guidance needs to be followed, and when decisions are being made about locating a house in the countryside, with no connection to a public sewer, site characterisation needs to be conducted prior to a decision being made on whether or not permission should be granted for the house. Houses should only be built in situations where the site is suitable for the treatment of the sewage being discharged from the house or where an adequate level of treatment is being provided.

JC: Are septic tanks a particular problem?

MC: Septic tanks, if built and operated properly are fine; they work, and they can also be relatively cheap. A lot of the same issues, particularly about the risk to ground water, apply with other systems as well as septic tanks, because the discharge from any onsite treatment system contains bacteria, and it is the bacteria that are a risk to drinking water supplies. The only way that can be dealt with, other than by disinfection, is by passing the effluent through a properly constructed percolation area, which applies both to septic tanks and to other onsite treatment systems. The issue really is that site characterisation is properly carried out, and that good decisions are made at the planning stage in relation to the type of system that needs to be put in. Following the installation of a system, a check should be made by or on behalf of the local authority that the system has been properly installed.

JC: What role do Agrement Certificates play?

MC: The Agrement Certificates state that the system will meet a specific standard, but what they do not do is give a guarantee that that standard is going to be met. That will depend on whether or not the system is maintained and cared for properly. The key issue for small waste water treatment systems is that whatever system is chosen, it is installed properly, maintained properly, and there must be some system of checks to ensure that this is happening. That can either be done by certified operators, by maintenance contractsor by local authority staff..

JC: In the events that systems are falling short, who takes action to rectify this?

MC: The local authorities have power to deal with situations where a small waste water treatment system is not functioning properly, and where its poor functioning is causing pollution. They can take action under the Water Pollution Act.

Related items

-

EPA launches air quality forecast

-

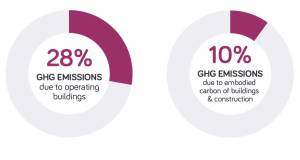

Property industry faces ‘triple threat’ from climate crisis

Property industry faces ‘triple threat’ from climate crisis -

Irish Green Building Council launch event to promote sustainable building practices

Irish Green Building Council launch event to promote sustainable building practices -

Ashden Awards winners showcase climate solutions

Ashden Awards winners showcase climate solutions -

‘Sufficiency’ key alongside energy efficiency & renewables, says IPCC

‘Sufficiency’ key alongside energy efficiency & renewables, says IPCC -

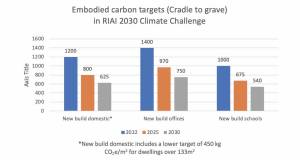

RIAI launches 2030 climate challenge

RIAI launches 2030 climate challenge -

Climate action plan sets embodied carbon targets for construction

Climate action plan sets embodied carbon targets for construction -

Grant invests in biofuel tech for oil boilers

Grant invests in biofuel tech for oil boilers -

Architects call for urgent climate action ahead of COP 26

Architects call for urgent climate action ahead of COP 26 -

EPA launches new green procurement guides

EPA launches new green procurement guides -

The PH+ guide to overheating

The PH+ guide to overheating -

Net zero carbon plans back renewables over fabric

Net zero carbon plans back renewables over fabric