- Feature

- Posted

Measure everything

A new housing scheme designed by Coady Architects in Wicklow has achieved the highest green home certification – while suggesting that the convictions of one practice on a single project can help to transform the industry.

Click here for project specs and suppliers

Project: 40-unit social housing scheme Method: Cavity wall on strip foundations

Location: Bray, Co Wicklow

Standard: HPI Gold

Embodied carbon: 687.5 kg CO2e/m2 (50-year design life)

BER: A2 (30 – 48 kWh/m2/yr)

Energy costs: €65 per month for 2 & 3 bedroom units (estimate of total energy costs, HPI assessment)

€65 per month

This is a normal housing development – built using block cavity wall on strip foundations – meeting the minimum building regulations brief from the local authority, Simon Keogh, senior project architect, is keen to stress. But, in many ways, this housing scheme is far from ordinary. Kilbride Court in Bray, County Wicklow, is the first multi-unit development to be awarded gold certification under the Home Performance Index (HPI), a certification system developed by the Irish Green Building Council (IGBC) to assess quality and sustainability in new residential developments.

The social housing scheme, completed in July, is the result of a three-year journey, and comprises 40 residences in Kilbride Court and two on Clover Hill. It includes terrace houses, duplexes, apartments and two single house units, the latter at Clover Hill which did not form part of the HPI application.

Throughout the project Keogh was passionate about gathering as much data on environmental impact as possible. Within the architectural profession, he says an “inherent problem lies in the inadequacy of our training specifically relating to the scientific performance of buildings”. He argues that there has been a systemic conflict within the education system and the architectural profession that places intangible artistic merit over measurable scientific performance.

“As a result, architecture has claimed for itself an elevated and near unaccountable position within society,” he says. “Architecture should not solely operate within a subjective sphere. The preference of art over science which our Anthropocene society has inherently consumed, has led us to face the still unresolved impact of climate change as identified as early as 1990.”

In many ways, this housing scheme is far from ordinary.

The irony, Keogh says, is that architectural ethics state that architects are obliged to protect and enhance the environment yet, so far, the profession has been seen enjoying its own intrinsic intangibleness. “There has been a long-neglected need to create science-based, tangible solutions. Part of good practice should have addressed the need to substantially reduce the 39 per cent of carbon dioxide emitted from the built environment.”

Keogh points out that this objective has been laid out again in the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report and in Ireland’s Climate Action Plan 2021, which calls for a substantial reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 and net zero by 2050. “If we continue to ignore the fundamental principles of good building practice the consequences experienced by society will be dire,” he says.

For Keogh, it was postgraduate training through courses in BIM (building information modelling) and professional energy skills in NZEB at the Dublin Institute of Technology — including a module on the passive house software, PHPP — that helped him “see the world from a scientific perspective”. He applied this expertise, and a healthy dose of steely determination, to Wicklow County Council’s housing scheme.

The Kilbride project wasn’t subject to the 2019 version of technical guidance document L. Planning was obtained long before the new regulations came into force, and the dwellings were up to wall plate level before the November 2020 deadline. But the scheme still comfortably exceeds the headline targets of Ireland’s nearly zero energy building (NZEB) standard. The 40 units achieved average energy performance coefficients of between 0.19 and 0.21, representing between 79 and 81 per cent reductions in calculated energy demand compared to Ireland’s 2005 regulations. This was not because of improved U-values but due to a modulating heat pump, improved airtightness and thermal modelling junctions delivering a Y-factor of 0.03 W/m2K.

But the HPI certification is a measure of sustainability that goes well beyond energy performance, explains Keogh. It is based on five categories of verifiable indicators and a point scoring system. The indicators are: environment, economy, health and wellbeing, quality assurance and sustainable location.

“The HPI is intended as a very holistic evaluation of the sustainability of new housing,” says Pat Barry, chief executive of the IGBC who, with environmental engineer Neoma Lira, developed the HPI. “The idea is to apply measurable indicators to a whole range of areas, including not only carbon emissions of energy, but also embodied carbon, biodiversity, land use, density, water use, design team skills and others,” he says. The HPI also assesses the sustainability of the location of housing, based on accessibility measurements relating to public transport, schools and amenities.

Achieving gold in the HPI requires an overall score equal to or greater than 70 per cent under version 1.1 (or 65 per cent under current version two). Some of the key scores for Kilbride Court were:

- 87 per cent in sustainable location

- 76 per cent in universal design

- calculated embodied carbon of 687.5 kg CO2 equivalent per square metre (CO2e/m2)

- used 81 per cent FSC timber

- used 68 products with EPDs or PEPs (see below)

- thermally modelled junctions to achieve an average Y-factor of 0.03 W/m2K.

But this task was far from easy, says Keogh. While it involved a lot of early planning, the greater challenge was the time required to ensure records were maintained and to complete the calculations. However, there are simple and free or low-cost actions that can be taken on a site to score points. For example, recording how sustainable the location is, logging construction waste to input into any life cycle assessments (LCAs), specifying restrictors on taps, implementing biodiversity measures or using products with environmental product declarations (EPDs) or product environmental passports (PEPs) to provide more accurate life cycle assessments.

“There are so many things that can be done on any site to start the journey. […] We are only starting to have the conversation now, but at least we are starting,” he says.

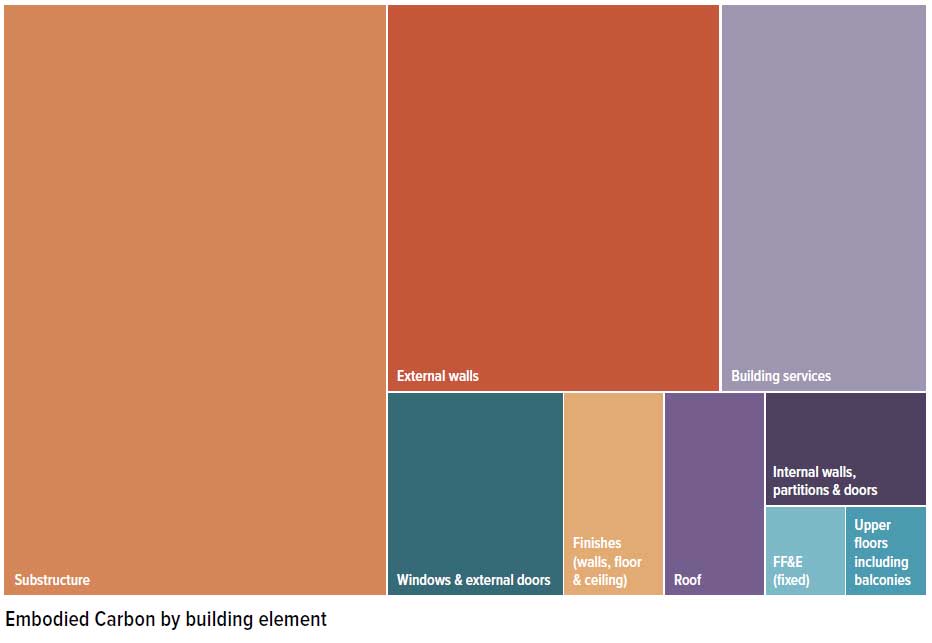

Embodied carbon

Thirty-nine per cent of global carbon emissions are related to building and construction. Of that figure, 28 per cent comes from operational carbon in the running of buildings, and 11 per cent from embodied carbon, which is all the CO2 emitted in producing buildings. With new buildings making substantial reductions in operational energy demand and associated carbon emissions, embodied carbon becomes increasingly important – and the HPI reflects this by awarding points for embodied carbon calculation and life cycle assessment.

Recording ecological change on a residential site is far from common.

Embodied carbon starts at the quarrying, mining, procurement or harvesting stage for raw materials, and continues as they are transformed into construction products, and transported and installed in buildings. It also includes the maintaining, replacing, removing and disposing of the materials throughout their life cycle.

Although the subject of embodied carbon has long been neglected, the signs are that this is set to change, and rapidly: Ireland’s recently published Climate Action Plan seeks to cut the embodied carbon of construction materials by 10 per cent as a core measure, with a further measure of up to 60 per cent reductions. A leaked draft of the next version of the EU’s Energy Performance of Buildings Directive includes proposals to mandate whole life carbon calculation in energy performance certificates for large buildings from 2027 and all buildings by 2030.

Meanwhile the RIAI has just followed the lead of RIBA in the UK by including embodied carbon targets in its own 2030 Climate Challenge – including a target of 625 kg CO2e/m2, and a higher target of 450 kg CO2e/m2 for dwellings over 133 square metres. Given the relative dearth of information on the embodied carbon of Irish buildings, one immediate priority is to start calculating embodied carbon, in order to benchmark existing buildings.

To produce the most accurate calculations possible, manufacturers need to step up to the plate by obtaining independently validated EPDs for their products. EPDs are a standardised way of providing data about seven key environmental impacts of a product through its life cycle. In Ireland, verified EPDs can be published on the EPD Ireland programme (www.igbc.ie/epd-home), developed by the IGBC, although it is important to note that an embodied carbon calculation can include data from EPDs published elsewhere – and EPDs are becoming common among European manufacturers.

“There is a perception in the industry that there are not many EPDs available in Ireland and that they are extremely expensive. That’s not always the case,” says Keogh. For Kilbride, he was able to accrue a total of 60 EPDs from product manufacturers and suppliers – the list of which is published in full below. By encouraging suppliers to get independently validated audits of the overall environmental impacts of their products through EPDs, Keogh has had a big impact on the supply chain. It is crucial, he says, for architects and everyone in the industry to “ask for EPDs. Don’t specify a product until it has an EPD would be an ideal scenario.”

For instance, he notes a growing number of Irish manufacturers leading the way with EPDs for a range of products. These include: Mannok for precast concrete slabs, blocks, roof tiles and insulation, Kilsaran for paving, Dulux for low VOC/SVOC (volatile and semi volatile organic compounds) paints, Medite Smartply for wood panel products, Gyproc for plasterboards, Ecocel, Kore and Xtratherm for insulation, Ecocem for green cement, Munster Joinery for windows, Passive Sills for thermally broken window sills, McGrath’s of Cong for screed, Techrete for precast concrete cladding, Tegral for slates and IMS for recycled aggregate, with Partel set to publish an EPD for their membranes in the new year.

Going against the construction industry culture where the architect’s specification may be broken on site by contractors or subcontractors substituting an alternative non-approved product, Keogh was a stickler for evidence that the specified performance was adhered to, conducting regular site inspections to protect the specification, EPDs and all. On one occasion, this led to a surprising finding. Low VOC/SVOC paints with EPDs were specified internally, and the contractor submitted Dulux paints, which were approved by Keogh. But when Keogh visited the site, he had reason to suspect Dulux paints weren’t being used, even though the subcontractors produced Dulux cans for inspection, because other empty cans of an alternative paint were found in the skips, indicating the painters had gone to the length of decanting the substitute paint into a Dulux can to avoid detection.

This article was originally published in issue 40 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

According to Pat Barry, the dogged determinism exhibited by practices like Coady Architects is already starting to have impacts far beyond specific projects, and is now driving verification of sustainability credentials across the supply chain. “This project shows there has been a real sea change in the level of transparency that manufacturers are now engaging at,” says Barry. “It’s projects like this which have made it possible. Now all the main manufacturers are developing EPDs. We now have over 100 products with EPDs. Hopefully we will see more really going for broke and really targeting high levels of sustainability,” he says.

“[In Ireland] we have to build half a million homes over the next 20 years,” notes Barry. “That’s where most of the environmental impacts from construction will come from. That’s why it’s so important to measure the full impact of building ordinary housing. That’s where we really have to target embodied carbon reductions,” he says.

With projects like Kilbride Court helping to create a benchmark for construction, Keogh’s focus is now shifting to delivering embodied carbon reductions.

“Concrete is responsible for eight per cent of global carbon emissions. We need to reduce the amount of concrete in our buildings,” says Keogh. For future housing projects, where cement products are required Coady will look for ways to reduce the embodied carbon of concrete, until alternatives to concrete become more mainstream.

This will include looking for higher quantities of ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBS) where possible, especially in dry concrete products where curing times are less critical, such as blocks, precast slabs, precast stairs, paving, lintols, and sills. GGBS is a by-product of steel manufacturing which offer reductions of up to 96 per cent in carbon dioxide equivalent emissions compared to ordinary Portland cement (OPC).

Keogh said that, in advance of a rumoured national technology centre for construction being formed shortly, with a remit to include holding data on building performance, the life cycle assessment results for Kilbride Court will be available on www.shareyourgreendesign.com.

Construction in progress

https://passivehouseplus.co.uk/magazine/feature/measure-everything#sigProId0e529f428a

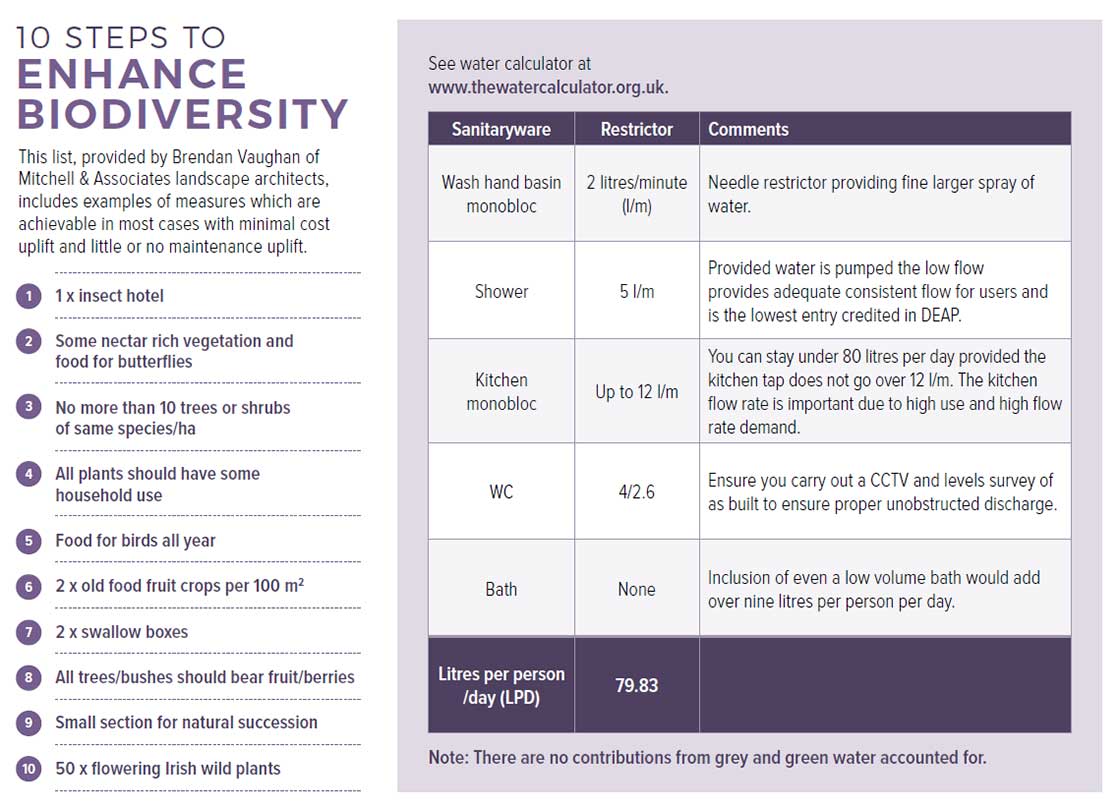

Controlling the flow

The Kilbride homes were designed to have exemplary levels of water efficiency, with an internal water flow rate of 79.8 litres per person per day, meeting the recently published RIAI (Royal Institute of the Architects of Ireland) climate targets for 2025 and just short of the 2030 target of less than 75 litres per person per day.

Flow restrictors are a simple and cost-effective way of controlling the water flow, notes Keogh, and they can be pre-installed by the manufacturers. Using restrictors at Kilbride, the wash hand basins achieved a flow rate of two litres per minute (l/m), the showers achieved five litres, and the WCs 4 to 2.6 litres, leaving the kitchen sinks at 12 litres.

This “is an easy win for the industry,” and the tool on www.watercalculator.co.uk is “a great simple method to calculate water use,” he says. This also reduces energy use – and not just in terms of the hidden energy costs of supplying sanitary water to the site. With the exception of the WCs, all of the water saving measures reduce domestic hot water use.

Assessing biodiversity change

One of the environmental indicators used in the HPI is ecology, which is assessed by measuring the ecological footprint of the development, explains Nick Marchant, ecological consultant at NM Ecology, who prepared a biodiversity management plan for Kilbride Court. This involved assessing the ecology of the area before and after the development.

In 2016, before construction, Marchant did a general ecological assessment of the site, recording the habitats and species present, as well as species of note or likely to occur on the site but not easily observed during the day, such as bats. This was followed by recommendations to minimise the ecological impacts of the development and enhance biodiversity, such as installing bird boxes to provide nesting opportunities for common species such as robins and tits, and including native trees in the landscaping. For example, rowan, a tree species which produces berries eaten by birds in autumn and winter, was used, says Marchant, adding that herbs were also included in the plan.

At the end of the project, Marchant did another assessment, counting the number of species and ensuring enhancement measures were put in place. The HPI asks whether there is a change in ecological value of the site before and after the development, based on the number of species recorded in each habitat and the area of each habitat. This change is calculated using IGBC’s ecology calculator and, in the case of Kilbride Court, there was a decrease in ecological value, resulting in a negative value of -11.2 in the HPI scheme.

Recording ecological change on a residential site is far from common, and Kilbride Court provides an important baseline for future schemes. “It is important to declare these values and to consider biodiversity in all construction and design, including passive houses,” says Keogh. “Now we have a measurement to go with. The key is to make it better and improve on it,” he says.

Marchant notes that the latest version of the HPI technical manual – version 2.0 on homeperformanceindex.ie – provides an additional way of assessing ecology, as well as the change in ecological value. “As an alternative, you can choose from a list of optional ecological enhancements,” such as including bat boxes and bird boxes, he says.

In new developments, says Marchant, simple, low-cost measures, such as planting native trees, inserting linear landscape features for animals to move and feed alongside, leaving dark areas for bats to feed, or putting in small water features, can enhance biodiversity. “But it’s also beneficial for the people who live in the houses. I think it’s a win-win,” he says.

Other low cost or free measures include adding an insect hotel, nectar-rich vegetation, swallow boxes, mixed species of trees or bushes, berry or fruit-bearing trees and bushes, and year-round bird food. Energy and environmental monitoring The measurements did not stop when the homes were built. Data is being collected and analysed remotely since the residents moved into the homes in July.

Ian Pyburn, innovation consultant with Integrated Environmental Solutions (IES), has been monitoring environmental and energy-related data in Kilbride as part of the AMBER (Assessment Methodology for Building Energy Rating) project. AMBER, which has been running since 2018 and is funded by the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland, is analysing BER and sensor data from 100 domestic and 25 to 40 non-domestic A-rated buildings.

The project is examining the indoor environmental quality of the Kilbride homes by gathering data on CO2, relative humidity and internal temperature, says Pyburn. Data from the homes is collected using an internet of things network called Lorawan, which relies on four or five environmental sensors in each home feeding data from individual rooms to a gateway, and then on to a data analytics platform. The sensors do not require Wi-Fi, and use a radio frequency instead. Once the results are analysed, the goal is to provide recommendations to the tenants in Kilbride on how to improve health and well-being in their homes.

In parallel, energy consumption is being assessed using IES’s well known software, IES Virtual Environment. Using digitised physics to work out how a building acts in real life – with real weather data and real thermal simulation – the project team recreated the Kilbride buildings. The models are then compared to the BER tool which was used in the design, to see how the buildings are performing and what elements of the BER methodology can be improved to be more representative of real-life buildings.

The aim is to provide guidelines to minimise the performance gap in A-rated buildings. “We want [to] see how our software models predict energy consumption, and feed that information back to the architects,” Pyburn says.

A pioneering project

“I applaud the diligence of the design team in sticking with the level of work that they put into achieving [HPI] gold. It’s a case of one person driving something single-mindedly and achieving it,” says Pat Barry. Ultimately, he says, “we need to move to low-carbon forms of construction, and walkable or cyclable communities. That’s the only way we’re going to actually achieve a world where we stay under 1.5 degrees [centigrade] of warming. We have to slash the number of cars on the road and move towards zero carbon homes built with zero carbon products, zero carbon operations and shared car ownership,” he says.

In the wake of the climate and biodiversity emergencies, the key achievement of the Kilbride housing scheme lies in the environmental impact data and metrics it can now hand over to future projects. In including metrics such as embodied carbon, ecological value and construction waste, which are still rarely considered, it delivers baseline data for a typical housing scheme in Ireland, says Keogh.

Don’t specify a product until it has an EPD would be an ideal scenario.

“If we don’t measure something, we cannot improve it. Developing high quality data is a critical first step in building more sustainable homes,” he says. Going forward, he believes there is a “dire” need for legislation in embodied carbon and in biodiversity, and to think about “how different methods of construction impact on emissions now, to prepare for the mammoth tasks of net zero by 2050 in line with the Climate Action Plan 2021”. But it’s empowering to think that “everyone can do something right now,” says Keogh. And the Kilbride Court project demonstrates just that.

Environmental product declaration schedule

Product type & location |

Supplier & product name |

Windows & Doors |

|

| Timber aluclad windows & external doors | Munster Joinery timber aluclad windows |

Ground / Intermediate Floor Slab |

|

| Structural insulation (threshold) | Partel - Alma Vert |

| Insulation - below slab | Mannok - Therm Floor / MF |

| Radon DPM membrane system | Necoflex - Monarflex RMB400 radon, air and moisture protection system |

| Precast concrete hollow core slabs to house type C & E flooring | Mannok - Hollowcore Slabs |

| Metal suspended ceiling system (compartment ceilings, lean-to roofs, and porches) |

Saint-Gobain - CasoLine MF |

| Mineral wool insulation (to ceilings beneath apartments to reduce airborne noise) | Rockwool - RW 3 |

Exterior Walls |

|

| AAC blocks (multiple locations) | Mannok - Mannok Aircrete |

| Insulation – cavity partial fill | Xtratherm – Xtroliner XO/CW (T&G) |

| 12.5mm hardcoat plaster | Saint-Gobain - Gyproc Hardcoat |

| Skim coat plaster | Saint Gobain -Gyproc Finish Plaster |

| Insulation (below ground to cavity) | Xtratherm XPS (generic XPS EPD from European Extruded Polystyrene Insulation Board Association) |

Roof |

|

| Concrete roof tiles (to all roofs except house type G lean-to rectification) | Mannok - Rathmore |

| Cellulose insulation | Dammstatt (Generic cellulose EPD from European Cellulose Insulation Association) |

| Vapour permeable sheet roof underlay (house type G lean-to roof rectification) | DuPont - Tyvek Supro breather membrane |

| Mineral wool insulation (between rafters to lean-to roofs and internal studwork) | Rockwool - Flexi |

| Fire cavity barriers (top of cavity walls) | Rockwool - TCB |

| Fire cavity barriers (junction party wall @ eaves) | Rockwool - SP 60 |

| Mineral wool insulation (fire stopping below roofing membrane and top of raked party walls) | Rockwool - RWA |

| Mineral wool insulation reinforced with chicken wire (fire stopping below roof tiles and above roofing membrane at party walls) | Rockwool - Fire barrier system |

| Rigid insulation under ceiling rafters to all lean-to roofs | Kingspan Kooltherm K107 |

| Rigid insulation – under AVCL to recessed porch | Kingspan - Kooltherm K110 |

| 9mm cement board (to canopy) | ETEX - Cedral fibre cement façade panels |

| Rigid insulation (under water tanks) | Xtratherm - XtroLiner XO/PR (PIR) |

| Natural rolled zinc pre-weathered with phosphorous mist (to canopy) | VM Zinc - Quartz |

Interior walls |

|

| 70mm metal studwork | Saint-Gobain - Gyproc Gypframe |

| Wallboard | Saint-Gobain - Gyproc Wallboard |

| Moisture resistant plasterboard | Saint-Gobain - Gyproc Moisture Resistant |

| Fireline board (duplex and apts) | Saint-Gobain - Gyproc Fireline Board (Cavan) |

| Soundbloc (heat pump internal unit) | Saint-Gobain - Gyproc Soundbloc |

| Paint timber internal (doors, stairs, etc ), Block 10 only | AkzoNobel - Dulux Trade Quick Dry Satinwood |

| Paint timber internal (doors, stairs etc), Block 10 only) | AkzoNobel - Dulux Trade Quick Dry Undercoat |

| Matt plaster paint - all plastered walls and ceilings | Johnstone's Trade - Jonmat Premium Contract Matt |

| Satin wood paint - all wood work | Johnstone's Trade - Acrylic Satin |

Miscellaneous |

|

| External paint (back wall only due to neighbour requirements) | AkzoNobel - Dulux Weathershield |

| Vinyl flooring (WC and bathroom) | Polyflor - PolySafe Standard PUR |

| Vinyl flooring (Wet rooms for house type D) | Polyflor - Polyflor PolySafe Hydro 36 + |

| Strong dispersion-based adhesive vinyl to wet rooms (non acoustic) | Uzin - Uzin KE 2000 S |

| Acoustic mineral wool lining (to party walls) | Saint Gobain - Isover Acoustic Partition Roll |

| Low slump floor Screed to falls (shower areas) |

Sopro - RAM 3 |

| Floor screed (patching/feathering concrete floors) | Sopro - Rapidur |

| Self levelling floor compound fibre reinforced(plywood flooring to bathroom on timber floor and concrete floor) | Mapei - Ultraplan |

| Concrete primer (prior adhesive ) | Mapei - Primer MF |

| Adheseive for ceramic tiles | Mapei - Keraflex |

| Adhesive for resilient and textile floorings | Mapei - Ultrabond ECO Vs90 plus |

| Anti-corrosion cementitious mortar for steel reinforcement rods (exposed steel to landing in house type C and exposed bolts to canopies to BF | Mapei - Mapefer Mapegrout T 60 |

| External permeable paving under brown bin to communal bin area | Kilsaran - Clima Pave |

| Foil faced insulation (all DCV reducing condensation /SVP reducing noise ) | Saint-Gobain - Isover Climcover Roll Alu2 |

| MDF trade sheeting (painted boxing out generally to non-wet areas) | Medite Smartply - Medite Trade MDF |

| MDF premier sheeting (build up stairs bottom landing to comply with Part K to ensure consistent risers) | Medite Smartply - Medite Premium MDF |

| MDF MR (window board and boxing out to WCs generally) |

Medite Smartply- Medite MR |

| OSB 2 (door ope linings - temporary) | Medite Smartply- Smartply OSB 2 |

| OSB 3 (12mm raking to stub ends, and 18mm kickerboard to attic) | Medite Smartply - Smartply Max OSB 3 |

| OSB 3 T and G (attic flooring) | Medite Smartply- Smartply Max OSB 3 T and G |

| OSB 4 (under tank and under canopy zinc roofing) | Medite Smartply- Smartply Ultima |

| Patching compound (to concrete floors near threshold) | Ardex - Feather Finish (rapid drying patching and smooth compound) |

| Roof membrane lean to rear roof rectification (to house type G) | DuPont - Tyvek 2507B |

| Air to water heat pump | Uniclima - Joint Product Environmental Profile Air/Water Heat Pump for individual housing (generic PEP) |

| Demand controlled ventilation system | Uniclima - Joint Product Environmental ProfileUnidirectional ventilation for dwelling, hygo-adjustable by low power extraction (generic) |

Embodied carbon calculation

An end-of-terrace unit, House Type A, was selected for an embodied carbon calculation conducted by John Butler Sustainable Building Consultancy, in an effort to compare the spec at Kilbride Court against the targets in the 2030 RIAI Climate Challenge. Butler conducted two separate analyses – one using One Click LCA, and the other using PHribbon.

As the RIAI challenge is measured against the EU’s Level(s) sustainable buildings framework, the building’s design lifespan was assumed to be 50 years as specified within Level(s), as opposed to 60 years in the 2017 RICS paper (‘Whole life carbon assessment for the built environment’) which underpins the RIBA targets. Butler also assessed the buildings against the 60-year design life targets in both software tools to enable comparison, leading to some stark differences.

In PHribbon, House Type A posted cradle to grave scores of 687.5 kg CO2e/ m2 of gross internal area with a 50-year lifespan, or 782 kg CO2e/m2 with a 60- year lifespan. This means that the project would fail to comply with the RIAI 2030 target of 625 kg CO2e/m2 (when 50 years is assumed), and would fail by a greater extent to meet the seemingly identical RIBA 2030 target of 625 kg CO2e/m2 (when 60 years is assumed).

The difference in totals was mainly down to replacement cycles for heat pumps and windows. The EPD for the Munster Joinery windows include a service life of 50 years, while the PEPs for the heat pumps and ventilation system estimate a 17-year life span, meaning three replacements within sixty years, rather than two within fifty years. Meanwhile in One Click LCA, House Type A posted scores of 718.1 kg CO2e/m2 (50 years) and 816.7 kg CO2e/ m2 (60 years).

An estimated 38.5 kg CO2e of the totals in PHribbon were attributed to transporting excavated soil and stone from the site – a total of 3.4 tonnes of CO2e attributed to this house type. In total, 30,274 tonnes of earth were excavated and transported from the site for disposal – plus a further 583 tonnes of mixed waste, totalling 1,497 journeys, including 930 to Roadstone’s Huntstown site in North Dublin, with other trips to facilities in Wicklow, Meath and Louth. Analysis by Passive House Plus estimated the average journey distance to be 42.6 km. In the vast majority of cases return trips were made to the site on the same day.

Taking a conservative approach, and allowing for an empty return journey in each case, the total distance travelled reached 127,431 km – over three times the circumference of the earth. This was estimated – based on UK government emissions factors for heavy arctic trucks – at 128.9 tonnes of CO2e for the whole development, with 3.45 tonnes attributed to the house type in this analysis based on its fraction of the total scheme’s gross internal area.

A separate analysis conducted by Irish transport emissions expert Conor Molloy of AEMS, based on Irish emissions factors for heavy arctics and an average load factor of 60 per cent (effectively meaning 40 per cent of journeys are assumed to be empty running) came in at 125 to 135 tonnes CO2e, depending on whether Irish or Global Logistics Emissions Council fuel economy factors are used.

Selected project details

Client: Wicklow County Council

Architects/project management: Coady Architects

M & E/structural engineer/energy consultant: Hayes Higgins Partnership

Landscape architects: Mitchell & Associates

Ecologist: NM Ecology Ireland

Main contractors/quantity surveyors: MDY Construction

Airtightness tester/consultant/ BER assessor: Building Envelope Technologies

Post occupancy evaluation: IES

Building life cycle assessment: John Butler Sustainable Building Consultancy

Mechanical contractor: Ashgrove Mechanical

Electrical contractor: HAL Electrical

Thermal blocks, hollow core, concrete roof tiles, insulation: Mannok

Wall insulation: Xtratherm

Thermally broken thresholds & roof membrane: Partel

Roof insulation & airtightness products: Ecological Building Systems

Mineral wool, plaster board, plaster & suspended ceilings: Saint-Gobain

Fire breaks & stone wool insulation: Rockwool

Windows and doors: Munster Joinery

Screeds: Smet

Permeable paving: Kilsaran

Paints: Akzonobel

Wood panel products: Medite Smartply

Heat pumps: Daikin

Mechanical ventilation: Aerhaus

Water conserving fittings & sanitaryware: Sonas Bathrooms

Water testing: Fitz Scientific

In detail

Building type: 40 x one, two, three & four-bed terrace houses, duplexes and apartments, totalling 3,320 m2

Location: Kilbride Lane, Bray, County Wicklow

Completion date: July 2021

Budget: €9m contract costs excluding VAT but including landscaping

Primary energy demand (DEAP, so regulated loads only): 37 kWh/m2/yr

Space heating demand (DEAP): 23 kWh/m2/yr (average)

Energy performance coefficient (EPC): 0.19 – 0.21

Carbon performance coefficient (CPC): 0.18 – 0.20

BER: A2 (30 – 48 kWh/m2/yr, or 37 kWh/m2/yr average)

Environmental assessment method: Home Performance Index Gold certified

Embodied carbon (based on house type A): 687.5 kg CO2e/m2 (when measured using PHribbon, assuming 50 year design life)

Density: 51.6 units per hectare

Change in ecological value: -11.2

Sustainable location: 87 per cent

Universal design: 76 per cent

Internal water flow rate: 79.8 litres per person per day

Overheating: Not significant (DEAP)

Daylighting: (35 units) living spaces with 3 per cent daylight factor and bedrooms at 1.5 per cent, (5 units) living spaces at 2 per cent and bedrooms 1.5 per cent

CO2 levels: 29 units being monitored, with results due in Oct 2022

VOC/SVOC: HPI not passed as polyurethane to handrails did not meet Ecolabel standard

Formaldehyde: Not tested

Radon: Target of 200 Bq/m3 per EPA standard (testing to be carried out)

Measured energy consumption: Pending

(29 units only under SEAI AMBER project)

Airtightness: Average result across all units of 1.64 m3/m2/hr at 50 Pa

Energy costs: HPI assessment report

estimates monthly total energy bills of €46 (1 bed units), €64 (2 bed), €65 (3 bed) and €95 (4 bed). Figures based on SEAI price data and include VAT but not standing charges.

Thermal bridging: 0.03 W/m2K (average) with reduction measures. Standard construction with first course of Mannok Aircrete blocks, and stubb truss only. Modular door thresholds developed by Partel with Alma Vert recycled PET structural insulation.

Energy bills (estimated in line with Home Performance Index):

1 bed: €48.00/month

2 bed: €63.00/month

3 bed: €65.00/month

2 bed: €95.00/month

Ground floor: Strip foundation and 150 mm in-situ concrete ground bearing slab with Mannok Therm Floor / MF 150 mm PIR insulation (lambda: 0.022 W/mK). U-value: 0.12 W/m2K

Walls: 102 mm facing brick / 18 mm render on 100 mm concrete block outer leaf with 80 mm PIR partial fill insulation (0.021 W/mK), 100 mm concrete block inner and 12.5 mm sand cement base coat with 2.5 gypsum plaster finish coat leaf. U-value: 0.21 W/m2K

Roof: Mannok Rathmore concrete interlocking tiles externally, followed inside by 37 mm sw batten, on Partel Exoperm Mono Duro 200 breather underlay, on sw prefabricated stubb trusses with 300 mm Dämmstatt cellulose (0.037 W/mK), on pro clima Intello Plus, on 12.5 mm Gyproc plasterboard with 2.5 mm gypsum skim finish plaster. U-value: 0.13 W/m2K

Windows: Munster Joinery double glazed, argon-filled aluclad timber windows. U-value of 1.2 W/m2K

Heating system: Daikin Altherma 3 air-to-water heat pump supplying low temp rads and 230 litre buffer tank.

Ventilation: Aldes Compact Micro-Watt SP centralised mechanical extract ventilation.

Internal water flow rate: 79.8 litres per person per day (calculated using www. thewatercalculator.org.uk) using restrictors. 5 litres per minute (showers), 2 l/m (wash hand basin taps), 12 l/m (kitchen mixer taps), and 4/2.4 litres (WC dual flush).

External water: 270 litre water butts

FSC/PEFC certified timber: 81 per cent

Environmental product declarations: 66 products (including 64 product specific EPDs, 2 industry association EPDs, and 2 industry association Product Environmental Passports, which are analogous to EPDs.

Water testing: Passed

Construction waste: Mixed waste: 583 tons

Muck away waste: 30,274 tons

Image gallery

https://passivehouseplus.co.uk/magazine/feature/measure-everything#sigProId09e96cceda