- Feature

- Posted

Pilot light - Pioneering Donegal deep retrofit a roaring success

A rundown 1970s scheme of one-bedroom, single storey social housing units in Ballyshannon, Co Donegal, has been transformed into a pioneering development of cosy, A-rated, NZEB-busting homes. The pioneering project – the first completed under Ireland’s deep retrofit pilot scheme – also breathed new life into an unloved green area and is expected to help fuel a regeneration project in the town.

Click here for project specs and suppliers

€23 per month for all energy

Building: Deep retrofit of 1970s social housing scheme

Location: Ballyshannon, Co Donegal

Standard: Nearly Zero Energy Buildings (NZEBs)

Prior to its refurbishment, the Ernedale Heights scheme of social housing in Ballyshannon, Co Donegal, presented a rogue’s gallery of problems. The three terraces of 11 homes were dark and cold. Despite the fact that they sat on a site that enjoyed a lot of southern sunshine, they faced north, away from the green areas that lay between them.

Poor ventilation led to condensation, damp and mould growth – a major health concern for the elderly residents, and this was exacerbated by leaky roofs and insulation-free walls.

The only heat sources were solid fuel fires and storage heaters, while the cramped design caused a raft of accessibility issues.

Brian Carey of Clúid, the housing association which refurbished the homes, explains that conditions were so bad that five of the houses were uninhabitable and had been boarded up.

“You’re talking single glazed windows and zero insulation. These were built back in the 1970s, and nothing had been done with them since then apart from emergency repairs. You had black mould along the tops and bottoms of the walls and no south-facing windows, so they were very cold and dark. Even though they’re small – no more than 35 m2 – they were very poorly laid out and did not make the most of the space.”

This article was originally published in issue 34 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

Though the houses were not designed for older people, most of the tenants had been in situ for many years, and the majority had passed retirement age. So, the residents spent most of their time inside, leading to a very high heat demand. Heating bills were astronomical – as much as €4,000 per year for a three-room house (that’s three rooms, not three bedrooms), and the dwellings also required near-constant maintenance.

Despite all this, residents loved the area. The estate is centrally situated – less than five minutes from the centre of Ballyshannon.

Between the coastal location and the strong sense of community, there was a great appetite from the tenants to stay put and make the most of what they had.

Brian Carey explains that the houses were originally owned by Donegal County Council, and that Clúid reached an agreement with the council to take ownership of the estate and regenerate it. The tenancies would transfer to Clúid on completion. The uninhabited houses would be filled with people from the council’s waiting list.

Heating bills are now a fraction of what they were.

In 2015, Clúid – the largest housing association in Ireland – started to look into the feasibility of addressing the shortcomings of the houses. Given the extent of the issues, a piecemeal solution was never going to work.

The conclusion was that a refurbishment programme could be undertaken, albeit within very tight budgetary constraints.

“We considered demolition,” says Carey, “but there were two reasons why it didn’t happen, the cost and the model. A new build would have been way out of our budget. Planning conditions would have required an increase in size from 35 to at least 52 m2. That on its own would have driven costs higher.”

In addition, he explains, refurbishment was the preferred choice of Donegal County Council. They wanted to maintain the connection with these long-established houses and saw the project as a kind of pilot. The entire area had become quite run down in the intervening years and Ernedale Heights could act as a standard bearer for a broader regeneration programme.

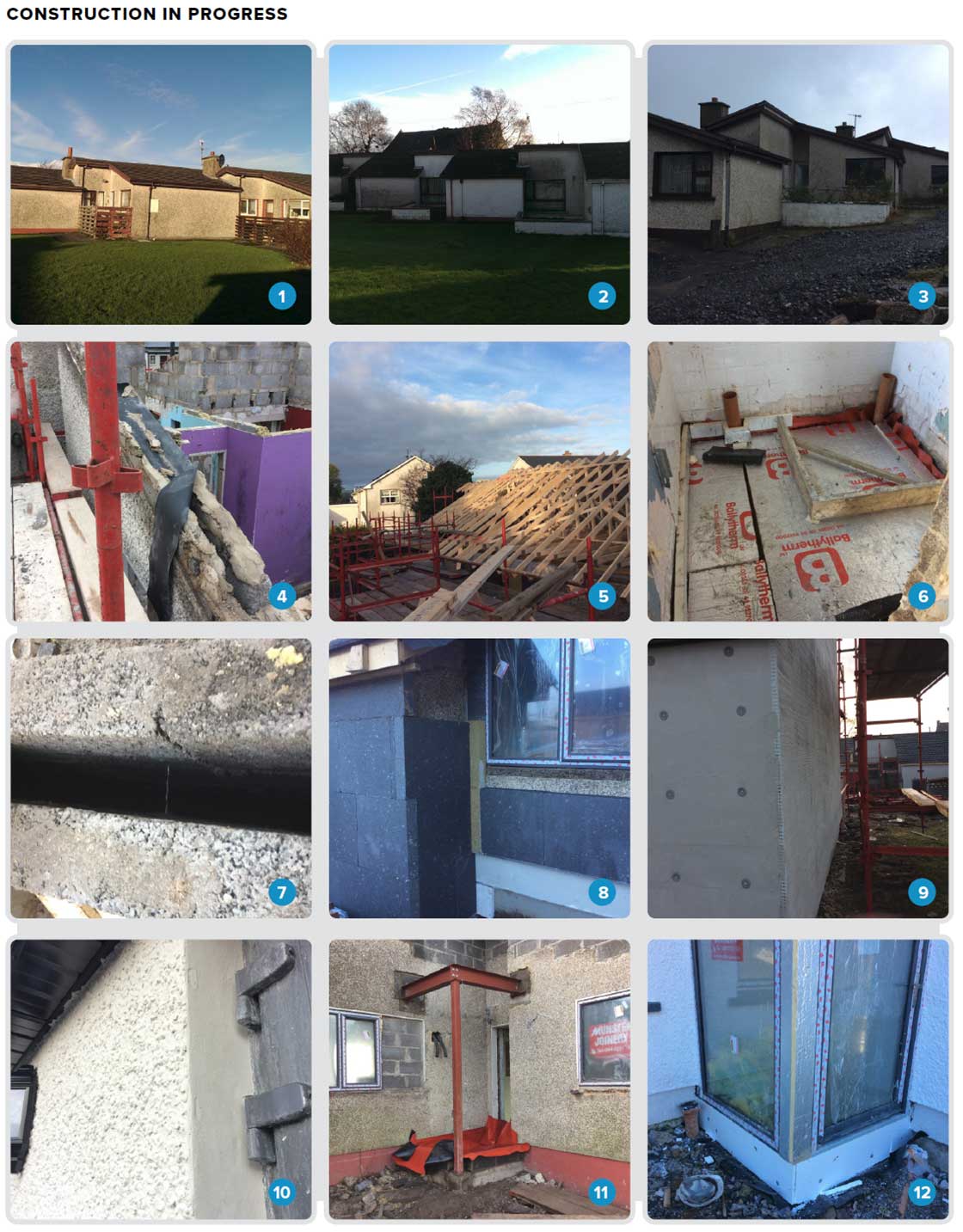

1, 2 & 3 The Ernedale Heights scheme of social housing prior to refurbishment. The 11 homes were dark and cold, and faced north, away from the green areas that lay between them; 4 the original wall cavities were uninsulated; 5 the slopes of the original roofs were too shallow, so they had to be taken down and rebuilt; 6 Ballytherm PIR insulation was installed where bathroom floors were taken up to create level access; 7 looking into the original 70 mm wall cavity before it was insulated; 8, 9 & 10 an external wall insulation system from Pw Thermal was chosen instead of internal drylining, thereby improving thermal performance without reducing internal space. It features 100 mm Kingspan Platinum EPS insulation, with a wet dash finish; 11 & 12 installation of the new front door — all windows and doors are double glazed units from Munster Joinery.

Clúid funds its activities through a combination of private and public loan finance. The former comes from the Housing Finance Agency, while the latter takes the form of a capital advanced loan facility (CALF) direct from the Department of Housing. There is a rigorous approval process to qualify for these loans, and all financing has to be in place before the go ahead is given to begin work.

The budget is always the starting point of a project of this nature, says Carey. “We don’t start with a lovely set of drawings. We see that we have X amount of money and ask, ‘What can we do with it?’”

Next, Clúid and the county council began a series of consultative meetings with residents.

“We wanted them to be part of the story,” says Carey. “These were the houses that they had been living in, and that they would return to. There was no point rebuilding the houses unless we dealt with the issues they had. We got them to list their problems, and there was a common thread. Cold, damp, lack of light, uneconomical and so on. This became our starting point.”

Gary O’Connor of project architects, Rhatigan Architects, takes up the story. “The consultation process allowed us to ascertain the good and the bad of living in those houses, what were the items that they felt needed addressing, what inherent problems did the houses have. We had another forum once we developed our design and presented it to the residents. We outlined the works that we were going to do and got further input from them.”

The consultation process, combined with a detailed survey of the houses, made it clear that they would need to be gutted to achieve even the most basic compliance. Apart from the absence of insulation, the slopes of the roofs were too shallow, and they had to be taken down and rebuilt. The extent of these works meant that given budgetary constraints, the design team couldn’t be too ambitious.

They aimed for a C1 building energy rating (so between 151 to 175 kWh/m2/yr of primary energy demand, excluding plug loads).

It was at this point that the SEAI announced its deep retrofit pilot programme. Clúid approached SEAI, and this ultimately became the first project in the country to secure funding under the scheme. This enabled the team to go much further than their original design.

“All of a sudden, we were able to look at external wall insulation, heat pumps and PV panels. PV panels don’t suit everyone, but these tenants are in their houses all day, and so are in a position to use the power as it’s generated.”

The original plan had been to pump the cavities and dryline the internal walls. While these measures would have brought wall U-values to regulation levels, it would have meant shaving precious inches from an interior that was already very small. Now, in addition to pumping the cavities with bonded bead insulation, the design team had the resources to opt for an external wall insulation system from Pw Thermal instead of drylining – in this case a polymer modified NSAI Agrément certified system that replicates the traditional wet dash finish, chosen to thereby deliver much better thermal performance without reducing internal space.

Airtightness in the original houses was very poor; in excess of 12 air changes per hour on average. Gary O’Connor says that the walls were re-plastered internally with care taken to seal all penetrations, as well as new airtight roofs being installed. These measures delivered a final average result of 3.0 air changes per hour. Given that the site is in a windy, coastal area, this makes a huge difference to comfort levels.

The tenants were kept up to speed with what was happening throughout the build phase. Most were rehoused locally, and often came to see how things were progressing. Opening up the design to address the accessibility and orientation issues was of course key to the refurbishment.

“We looked closely at the living spaces,” says O’Connor, “working out how to maximize the benefit of the passive solar gain within. We decided to re-orient the houses so that they were facing south. We put in double doors that opened out to a generous patio, and that connected both sides of the houses. We also made them dual aspect, so that they linked to their neighbours.”

In addition to those vital solar gains, the re-orientation addressed one of the key problems the tenants had identified during the consultation phase – the fact that the houses were so dark. In turning them to face the sun, the architects were also able to make all of the spaces accessible, replacing internal and external steps with ramps. The front entrances are now much more accessible, and visible too, which gives a greater sense of security to the residents.

Inevitably, fresh challenges arose as the construction team began stripping the buildings down. The need to replace the roofs was discovered early on. In order to secure adequate airtightness and remove thermal bridges, the chimneys were also removed and the fireplaces blocked up.

One of the big issues with the original layout was that the green spaces between the three blocks were not overlooked. Brian Carey says: “To say that these were unloved would be putting it mildly.” There were no paths linking the green areas, and no planting to soften their barren look.

“For that reason, people didn’t engage with them. They didn’t meet here or go for walks or anything, so we put in little footpaths between the terraces, and each row is now connected through these well-tended lawns, which feature plants and flowers.”

The south-facing patios now look over these landscaped areas. The introduction of new boundary fencing and landscaped boundaries gives ownership of these spaces to tenants, and helps to stop others taking shortcuts through the site.

The tenants moved back in in December 2018, and so far, the reaction has been universally positive.

Each Clúid scheme has a dedicated housing officer to deal with any issues that the tenants may have. During normal times, he or she visits on a weekly basis to check in with tenants, and Clúid puts in place a planned maintenance programme too.

Despite the sophistication of the technology – Aereco demand controlled ventilation, PV panels and new Daikin air-to-air heat pumps, the tenants are confronted with simple controls – they only need to specify the temperature they require on a simpler digital controller, and there have been no issues as a result. “We’ve learned,” says Carey, “that you need to make it simple for people.

Heating bills are now a fraction of what they were. The dwellings even meet Ireland’s new build standard for nearly zero energy buildings (NZEBs), with energy and carbon performance coefficients all under 0.3 and 0.35 respectively, as required by the 2019 version of Part L of the building regulations (see ‘In detail’ for more).

“The difference between these houses, before and after, couldn’t have been more different – they were completely reconfigured,” Carey says. “All of the tenants were delighted with how they turned out. I called up a couple of weeks after they moved in and a couple of them were out on their patio drinking coffee. They were delighted to be back.”

Selected project details

Client: Clúid Housing Association

Architect: Rhatigan Architects

M&E engineer: Doran Professional Services

Civil & structural engineer: CHH Consulting Engineers

Main contractor: PJ Treacy & Sons

Quantity surveyor: Kilfeather QS

Mechanical contractor: Emmet Travers Plumbing, Heating & Gas

External insulation system: PW Thermal Building Solutions Ltd

EPS insulation (bead and boards): Kingspan Insulation

Insulation contractor: B Donaghey & Sons Ltd

Roof insulation: Knauf

Windows & doors: Munster Joinery

Roofing: Conwell Roofing

Heat pumps: Daikin, via Northern Refrigeration Services

Ventilation: Aereco, via Northern Refrigeration Services

Solar PV: Future Renewables

BER assessor: Nationwide Energy Consultants

In detail

Building: Deep retrofit of 11 x 1970s single-storey houses, all approx. 38 m2 floor area.

Location: Ernedale Heights, Ballyshannon, Co Donegal

Budget: €950,000

Completion date: May 2018

Space heating demand (DEAP, post-retrofit, sample dwelling): 28 kWh/m2/yr

Number of occupants: 1-2 per dwelling

Building Energy Rating (DEAP)

Before: Average of G (736 kWh/m2/yr), ranging from 409 kWh/m2/yr (F) to 866 kWh/m2/yr (G), the large range caused by differences in heating systems and the fact some dwellings had double glazing and some had single.

After: Average of A3 (56.50 kWh/m2/yr), ranging from 54.24 kWh/m2/yr to 58.91 kWh/ m2/yr)

Energy bills (measured or estimated)

Before: Using the estimated pre-retrofit delivered energy for an average dwelling at Ernedale Heights, Bonkers.ie suggests an annual electricity bill of at least €1,773 (cheapest suggested plan) at May 2020 electricity prices. This assumes equal use of day and night rate electricity. Figure includes VAT and standing charges. In reality, residents were not likely to have been using this much electricity as this assumes the house is heated to 21ºC in living areas & 18ºC elsewhere, which would probably not have been the case in practice.

After: Bonkers.ie suggests a cheapest annual available plan of €278 (€23 per month) based on average post-retrofit delivered energy (DEAP). This assumes equal use of day and night rate electricity. Figure includes VAT and standing charges.

Energy performance coefficient (DEAP): Average of 0.223, ranging from 0.217 to 0.23. Note 0.3 or lower is required to comply with Ireland’s definition of NZEB (Part L 2019).

Carbon performance coefficient (DEAP): Average of 0.213, ranging from 0.208 to 0.22. Note 0.35 or lower is required to comply with Ireland’s definition of NZEB (Part L 2019). Airtightness (at 50 Pascals)

Before: Average of 9.32 m3/hr/m2 (ranging from 7.95 m3/hr/m2 to 9.76 m3/hr/m2)

After: Average of 2.83 m3/hr/m2 (ranging from 2.44 m3/hr/m2 to 3.66 m3/hr/m2)

Ground floor

Before: Uninsulated concrete floor After (if upgraded): No general ground floor upgrades were undertaken within the scope of works, however in places where radon sumps were installed or bathroom floors were taken up to create level access, Ballytherm PIR insulation was installed.

Walls

Before: 100 mm rendered concrete block outer leaf and inner leaf with un-insulated 70 mm cavity.

After: 100 mm Pw Thermal Building Solutions external wall insulation with 100 mm Kingspan Platinum EPS insulation, followed inside by 100 mm original rendered block outer leaf, 70 mm cavity pumped with Ecobead cavity insulation, 100 mm masonry original inner leaf with new plaster finish. U-value: 0.17 W/m2K

Roof

Before: Insulation deteriorated to 25 mm.

After: Roadstone Donard flat pan interlocking roof tiles, on Tyvek roofing membrane, on new prefabricated timber trusses. Insulation was installed on the flat at joist level with 300 mm Knauf Earthwool fibre insulation with a thermal conductivity of 0.044W/mK laid in two layers; between joists and over joists to give a U-value of 0.13 W/m2K.

Windows & doors

Before: Single glazed, timber windows and doors. Overall approximate U-value: 3.50 W/ m2K

New windows: Munster Joinery double glazed windows and doors, with 6 mm clear float, low-emissivity coating, 16 mm Argon filled cavity, 6 mm solar control outer pane. Overall U-value of 1.20 W/m2K. Glazing oriented to south in renovated dwellings.

Heating system

Before: Open fire and portable electric heaters.

After: 1 x external Daikin air-to-air heat pump connecting to 2 x Daikin internal air conditioners per dwelling, one in the bedroom and one in the living room. Controlled via infra-red remote controller with temperature & timer function.

Ventilation

Before: No ventilation system. Reliant on infiltration, chimney and opening of windows for air changes.

After: Aereco demand controlled mechanical extract ventilation.

Electricity

Renusol VarioSole on roof system with 6 JA Solar – JAM6 60/265 with a rated output of 1,590Wp was installed to the roofs of each unit

Image gallery

https://passivehouseplus.co.uk/magazine/feature/pilot-light-pioneering-donegal-deep-retrofit-a-roaring-success#sigProId255a2bbbfa