- Insight

- Posted

SuperHomes scheme: a blueprint for cost-effective deep retrofit?

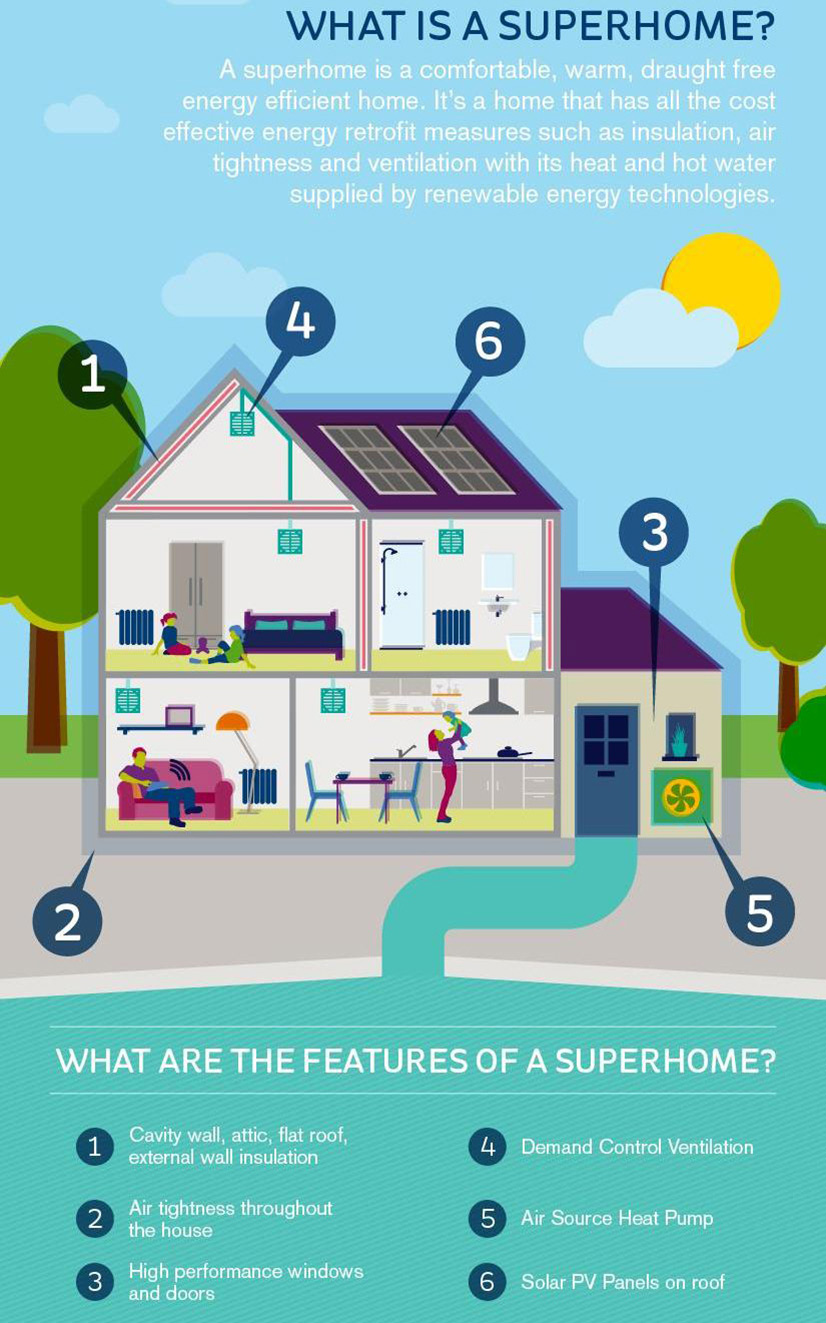

For a while now, schemes that aim to encourage the mass uptake of home energy upgrades — essential for cutting carbon emissions from our building stock — have tended to fall into two camps: those that focus on shallow measures like cavity wall insulation and new boilers, and deep retrofit like the Passive House Institute’s Enerphit standard. A new Irish retrofit scheme aims to point the way forward by bridging the gap between these two extremes.

This article was originally published in issue 18 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

For a number of years now, we’ve been trying to resolve the conundrum about how to stimulate deep retrofits of homes on a massive scale in order to reduce their carbon emissions in the most cost-effective way possible.

Better Energy Homes, the Irish government’s retrofit scheme, has gone some way to stimulating the retrofit market from a very low base with its support for individual measures such as roof, cavity wall and external wall insulation, high-efficiency fossil fuel boilers, and heating controls.

But few would disagree that mass retrofitting in Ireland, as in the UK, has to go further and deeper. Part of the problem is the yawning chasm in the retrofit market between shallow projects driven by the Better Energy Homes scheme at one end, and high-end retrofits to the Enerphit standard on the other.

Into this gap has jumped a ground-breaking new national scheme called SuperHomes.

(left to right) Aereco demand-controlled mechanical extract ventilation units have been installed on all SuperHomes projects to date to guarantee indoor air quality and protect occupant health. Fresh air enters through external grilles; EHT humidity sensitive air inlets modulate the ventilation rate subject to occupancy; the stale air is extracted through variable airflow BXC extract units.

Developed and run by the Tipperary Energy Agency (TEA) and funded by SEAI (the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland), it offers grant funding to cover up to 35% of the cost of upgrading pre-2006 homes to an A3 Building Energy Rating — up to a maximum eligible cost of €26,000 (excluding VAT).

Although an A3 BER is the upgrade target, SuperHomes also includes several mandatory measures that homeowners must complete to avail of financial support. The primary heating system must be renewable – and specifically an air-to-water heat pump or wood pellet boiler. Advanced ventilation systems must be installed, such as demand controlled mechanical extract ventilation or heat recovery ventilation. Finally, the building’s airtightness must be improved. Other non-mandatory measures, such as insulation, window and door upgrades, biomass stoves and solar PV arrays may be incorporated.

The scheme is clearly aimed at people who want to do more than a shallow retrofit, but who also don’t want to be using oil when there’s a realistic renewable energy option. And it’s all presented in a digestible, simple-tounderstand package.

“There’s no easy option and still there’s a lot of confusion, a lot of challenges about [people] actually doing what they think they want to do from an ethical or environmental or comfort point of view,” said TEA’s chief executive Paul Kenny. “We developed SuperHomes around trying to answer that need.”

The main lesson Kenny took from the spectacular failure of the UK’s Green Deal retrofit scheme, he said, was that while the advice homeowners received was clear, it wasn’t tailored to the individual property. So the essential sales concept TEA settled on was to organise an extensive survey and then design a comprehensive, holistic scheme that incorporates the most appropriate measures for a home, present it to the homeowners and say ‘this is what I would do’. Kenny said: “We make a grant offer to people based on what will work in their house and work for them.”

A house in Templemore, Co Tipperary that received three new air-to-water heat pumps, an Aereco demand-controlled ventilation system, 4kW solar PV array and airtightness measures under the SuperHomes scheme. The house achieved an airtightness test result of 5 air changes per hour

At first glance, the technical design of a typical SuperHome might read a bit like passive house lite, as two of the scheme’s three mandatory measures bear the hallmarks of the passive house approach – mechanical ventilation systems and airtightness. The non-mandatory measures, while important, are chosen depending on how well they will fit together in the retrofit’s proposed design, but also dependent on budgets.

The truth is that SuperHomes differs from a typical passive house approach, which “is really about 95% energy… use reduction mainly through building fabric measures, but for us its 20-30% reduction through fabric measures and another 20-40% through well designed, well commissioned heat pump use,” said Kenny.

SuperHomes also operates according to the law of diminishing returns. When saving energy gets above a certain cost, it’s just cheaper to generate it renewably, he says. “It’s the cost of energy efficiency versus the cost of renewable energy. SuperHomes has been designed to achieve the balance there. And it’s hugely challenging; most people have shied away from this type of thing.”

Based on monitoring together with feedback from participating homeowners, TEA has fine-tuned the initial pilot scheme involving 10 houses and is now in the process of completing 27 more SuperHomes this year.

The average net cost of the measures to the pilot homes was around €18,000 with the average payback period estimated at around 10 years.

And the feedback appears to be very positive, particularly regarding the comfort levels, which Kenny says is thanks to the combination of heating systems that are always on and windows that don’t need to be opened for ventilation, meaning that the average temperature inside is higher. Not to mention the level of indoor air quality. Kenny said: “You have comments like, we no longer smell the dogs, we no longer smell the son’s hurling kit, you know, all that sort of stuff. So you put that all into a mix and everyone is much happier with the solution.”

SuperHomes residents also report reduced condensation, which Kenny says is thanks to the combination of higher air temperatures generated by the always-on heat pump together with the reduced humidity brought about by the demand control ventilation. At the same time, he adds that SuperHomes has shied away from internal insulation because of the higher risk of interstitial condensation.

Kenny is also keen to dispel some of the fears and preconceptions that some contractors might have about getting involved in SuperHomes because so much of the work might be new to them, such as airtightness, ventilation and heat pumps.

Three air to water heat pumps

He said some of the contractors who pitched for work offered very uncompetitive quotes, presumably to mitigate what they perceived as some of the risks or uncertainty associated with retrofit work. But they are not expected to have much or any design input into a typical SuperHomes scheme, as this is the TEA’s domain. All contractors undergo training on the key works measures too before they even get on a site.

Paul O’Brien of SOLA Energy Solutions in Tipperary is a SuperHomes contractor. In the homes he has worked on so far, there have been no nasty surprises, and he likes how the scheme has helped take out much of the guesswork. “They make it very simple for us, we know exactly what we’re pricing.”

“The ventilation would have been new to us, none of us were trained up for that, but the heat pumps, we’ve some experience of installations but not for retrofitting.” Having since worked with both demand control ventilation and heat recovery systems, he much prefers the job of fitting the former.

He also appreciates more now how the installation of the heat pumps is a job that requires particular care, particularly if it aims to continue its recent emergence as a mainstream choice in heating systems.

The pumps themselves are also becoming more of a commodity item, but there’s still some way to go. “While it’s not the cheapest in terms of a ten year payback – we need to scale it up to get it cheaper, and incentivise its uptake,” said Kenny.

As well as the UK’s Green Deal, the TEA researched comparable retrofit schemes in other countries, including Germany’s development bank KFW’s energy efficient refurbishment scheme, and an eco-renovation scheme in Picardie, a rural area just south of Paris.

The KFW scheme has a number of stand-out features, including the all-important whole house approach to energy saving, but it also benefits from state-subsidised loans available at eye-poppingly low interest rates of between one and two per cent. If SuperHomes goes national — as is Kenny’s aim — getting the cheap finance conundrum cracked will be crucial.

“It needs a lot of work to make it national, but it’s viable and we’re clear on that,” he says.

Case study 1:

Charles Stanley Smith

Charles Stanley Smith and his wife live in a two-storey detached house built in 1993, and through the SuperHomes scheme he got the mandatory air source heat pump, demand control ventilation, airtightness, upgrades, along with new lower temperature radiators, cavity wall insulation, and the insulation of the attic space and flat roof. He also got the chimney permanently closed and the gas fire disconnected, and later had PV panels installed.

Like many environmentally-conscious homeowners, he had been keen to get his draughty house retrofitted for sometime, but was driven to distraction by the difficulties in researching individual measures and finding out what grants were available.

This made the tailored yet flexible approach provided by SuperHomes something of a panacea for Charles and his wife.

An Aereco demand-controlled ventilation system

“In some ways it’s much easier to have somebody else to explain that to my wife than me, because she’s getting a better view. I could have sat her down and said ‘the results of my googling are...’ but to have Paul [Kenny] come along and sit both of us down and go thorough our requirements together, was very reassuring for her.”

This extended to the business of getting a loan without having to pitch the merits of the scheme to AIB, which had agreed to provide finance to anyone who wanted a SuperHomes retrofit.

“A lot of my friends would like to do this because it’s too complicated trying to do it on your own… To have Paul come in and say, here’s your answer, all you have to do is sign here, and sign the cheque at the end of the day, was great. And you have absolute involvement in the whole thing.”

Previously a heavy user of oil and electricity for heating and hot water, he reckons he saves as much as €2,000 on his heating bills each year now.

Case study 2:

Seamus Hoyne

Before he learnt about SuperHomes, Seamus Hoyne – Kenny’s former boss at Tipperary Energy Agency – pretty much knew what needed to be done to bring his split-level bungalow to the energy-efficiency standard that he wanted.

Located in a rural area near Roscrea, Co Tipperary, the bare shell was built in 2005 but later abandoned due to the recession until Seamus and his family bought it in 2008 and finished it off. As part of this fit-out they installed solar thermal panels, a double-sided wood stove and did some insulation upgrades, but they wanted to do more.

“In principle, we want to do a comprehensive upgrade and knew that we had to do some work on ventilation and also on our windows and back door.

When the SuperHomes pilot scheme came along, it seemed to tick all their boxes and proved to be the incentive the family needed to actually get it done, said Seamus.

For a total investment of €17,000 (funded without a loan) of which 35pc was subsidised by the TEA, the Hoynes got the mandatory air source heat pump, demand control ventilation and airtightness upgrades, along with a new back door and triple-glazed windows. PV and external insulation were also on the wish list but ruled out due to the limited budget, though they hope to get PV in the near future.

Seamus is delighted with the comfort levels of the home. “Our split level bungalow has the childrens’ bedrooms in the low part of the building. There were emerging condensation issues and ventilation issues and the kids tended not to spend time there. The move to a low temperature heating profile in the building along with the ventilation upgrades has made this part of the home much more comfortable.”

Working out the savings in running costs is still a work in progress, but having previously spent around €230 a month on heating fuel (oil and wood), the heat pump is now costing €80 a month. So, along with reduced use of the wood stove, it looks like they are already saving well over €120 a month. Seamus expects a payback period of about nine years.

How SuperHomes was born

How SuperHomes came about and how it arrived at its particular retrofit model is an interesting story in itself. It began when Tipperary Energy Agency ran an EU-funded project called Serve (Sustainable Energy for the Rural Village Environment) from 2008 to 2012 that aimed to create a sustainable energy region in North Tipperary, part of which involved designing a successful retrofit programme for residents.

While they ended up doing some 1,400 mainly shallow retrofits under Serve, Kenny and his team were frustrated that houses upgraded under the programme didn’t go completely renewable. In planning its next retrofit scheme, the TEA resolved not to support oil boiler installations.

When they started looking more closely at domestic applications of air-to-water heat pumps, they were repeatedly warned off them for being too expensive or, because they needed low-temperature emitters (like underfloor heating) to work properly. But on realising that 20% of Sweden’s domestic heating is provided by heat pumps, and that they are common in the US, Kenny says “we thought to our ourselves, there must be a way”.

It was then that airtightness came into the equation. The theory goes that if you run heat pumps like boilers – cycling on and blasting high temperature heat in for a couple of hours, then cycling off – they won’t be very efficient. But if you use them for 24 hours, you can bring the temperature down and slash the energy consumption accordingly, but only if the house is airtight.

“So we thought, well we have to bring down the air leakage so that if we do extend the heating period using a heat pump, we won’t drive the energy consumption bananas.”

So they arranged to experiment with basic airtightness measures on five houses, including Kenny’s own home. “Our houses would have started between 9 and 14 air changes an hour and they came down to between two and five essentially. So you could probably say from an air leakage point of view we took 50-70% of the air leakage out of houses,” he said.

“And then we thought, if we bring the airtightness down we are not going to have enough fresh air, so we are going to have to do ventilation as well.” More research followed, spurred by Kenny’s personal interest in better air quality, and this led them to focus on mechanical ventilation, with demand control ventilation systems emerging as a cheaper and more straight-forward option for retrofit than heat recovery ventilation systems.

But if these are the mandatory measures, how do the non-mandatory measures fit into the equation, including insulation, window and door upgrades, PV panels etc?

This is where the homeowner has a degree of choice, says Kenny. “For example, if they have an exposed stone wall that’s 700mm thick in one part of the building but they really can’t insulate for one reason or another, for aesthetics or that it would ruin the character of the house, then we can do other things to make up for that. That might be fitting a much larger radiator to get higher efficiencies. We’re very, very flexible about how those solutions can be provided.”

Armed with its new retrofit model, the TEA pitched a pilot scheme of ten homes last year to SEAI, including a 10% unsecured loan from AIB and a whole lot of metering, and SuperHomes was born.