- New build

- Posted

Sideways West Cork house rests lightly on the land

This uncertified passive house on Ireland’s south-west coast makes a striking-yet-sensitive architectural statement.

Designing and building a landmark house for the ragged-but-stunning coast of West Cork is not easy. In such sensitive surroundings, many designers have built garish mansions, while others might have designed something plain and uninteresting.

But with this house near Castletownbere, built for his mother, architect Donn Ponnighaus has produced a dwelling that manages to make an architectural statement while sitting lightly in its surroundings, adding rather than subtracting from the landscape.

Donn’s mother Ita Molloy — a doctor who spent much of her career working in Africa — is originally from Westmeath. She bought a cottage on the site in 1993 to use as a holiday home, and later decided to retire here. The initial plan was to renovate and extend the cottage, but the conversation quickly turned to creating something new.

“What I really wanted was a house within the surrounding countryside. I wanted a house built into the hill in the field overlooking the mountains and the sea. We have got just a fabulous view with the windows down to Bere Island and out to the sea and across to the mountains,” Ita says.

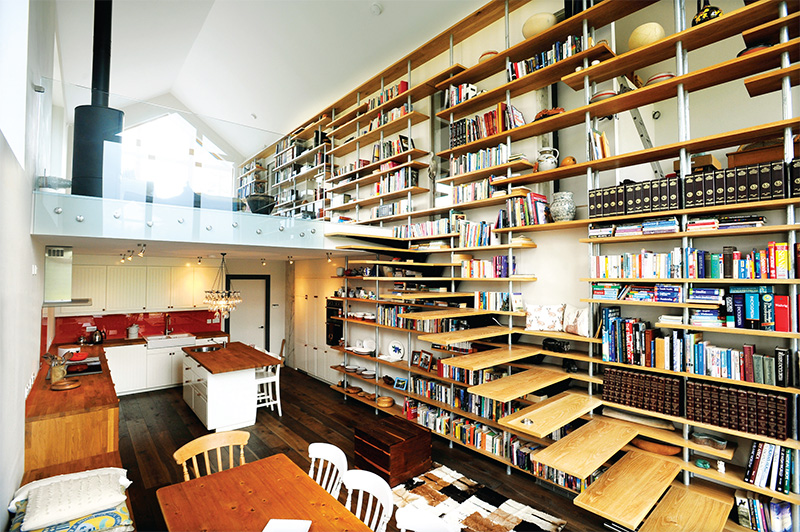

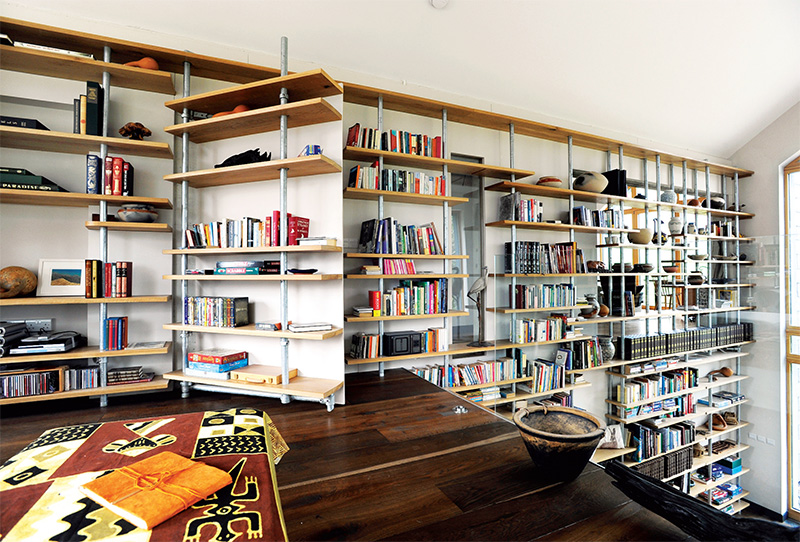

The house is divided into two living spaces, public and private, separated by a library wall with its own secret doors. A glass balustrade is yet to be installed

In 2011 Donn left his job with an architectural practice in England, where he had learned about the passive house standard. The following year he moved to Castletownbere to work full time as architect and project manager on this job. But his work in England was mostly on big commercial projects. He says: “I’d never built a house. I thought: am I biting off more than I can chew?”

Donn’s desire to reduce the house’s environmental impact was borne from his childhood in Malawi, where he witnessed a daily struggle to obtain resources, and the knock-on effect of habitat destruction as forests were cut down for fuel and arable land.

“Architectural education teaches you that over 50% of energy used by humans is in the production and running of buildings so from then on I started feeling a personal responsibility,” he says. “I always pushed for greater environmental design at every office I worked at, though I often ran head first into budget objections.”

“There are many different aspects of building an environmentally friendly house but I knew very little about the energy side of things. It's simply not something you learn as an architect except in the most basic way.”

Ita wanted the house to recede into the landscape, so it was decided to bury the ground floor in the hillside. This meant using a retaining concrete wall, for which Donn chose the Quad-Lock insulated concrete formwork system, which was erected by Fermanagh-based Passive Building Structures. For the sake of continuity and simplicity, Donn chose the same system on the first floor too.

“I could have put a timber frame on top, but I’m very aware that if a passive house fails it fails at the joints,” he says. The ICF system includes a 200mm reinforced concrete core with 160mm of EPS externally and 80mm EPS on the inside. The polystyrene panels are erected in a Lego-like fashion, then the concrete is poured down in between to set.

Passive Building Structures also supplied a polystyrene roofing system, Passive Roof Panel, for the house, with 220mm EPS panels used for the building’s vaulted ceilings. The panels were taped to a damp proof course embedded in the top of the ICF walls to ensure airtightness at a critical junction.

The morning of the air pressure test, the house yielded a good but far-from-passive result of 1.5 air changes per hour. It turned out the concrete in the ICF had not fully compacted in some places, meaning some patching up was needed. “We achieved 0.55 by the end of the day but it took four people all day finding the holes and patching them up.” Donn says.

“Airtightness is the hardest thing to explain to people until they have experienced a pressure test themselves and seen how air gets in the smallest cracks. I think general builders are very good at understanding how water works and how to deflect it away but understanding that air is a gas and behaves quiet differently will need some more time,” he says.

The thermal envelope is completed with a raft foundation system insulated with 160mm of EPS below the slab. Meanwhile 60mm of EPS around the slab perimeter joins the outer EPS layer of the ICF walls, and 60mm of Kingspan polyurethane above the slab joins the inner EPS layer of the ICF walls. The whole house is effectively wrapped twice in insulation. Meanwhile the windows are triple-glazed aluminium- clad timber Optiwin Alu2Wood units, manufactured in Wicklow by Ambiwood.

The house is primarily heated by a Nilan Compact P combined heat recovery ventilation and air-to-air heat pump system. This provides ventilation, air space heating (or cooling) and domestic hot water by utilising exhaust air from kitchens, utility and bathrooms. The conditioned air is then distributed by Nilair ducting to air supply grilles in the floors, while extract valves are in the ceilings. In this instance, the Compact P also includes a separate 3 kW Geo3 geothermal heating unit that draws on a horizontal ground loop in the garden.

ICF was also used to build the party wall between the house’s two sections. The insulation here was only needed as temporary formwork and a variety of different objects including fishing nets, bamboo, grass, leaves and sea shells were cast into the concrete

In winter the system first recovers heat from warm exhaust air, while the geothermal unit can be switched on to support air space heating or domestic hot water. The Geo3 distributes to underfloor heating pipes in two zones: the thermostatically controlled bedroom, and the main living spaces, which feature weather compensated controls.

The Compact P has a central controller placed in the living spaces for ventilation, temperature and humidity, while the Geo3 has its own control. “it just feels great to be able to control it – the ventilation rate and the temperature control as well,” Ita says.

Maurice Falvey of Nilan Ireland, who designed and supplied the system, adds: “From Donn’s point of view it’s a retirement house, so it’s got to be maintained in a comfortable way. The unit is set up so that it will automatically go into cooling if it reaches 25 or 26C.”

Passive house newcomer Donn credits Falvey, a veteran of passive house projects in Ireland, for helping him through the process. The house, named Teach Maoldia after the Irish for Molloy, also features a room-heating Jydepjsen wood burning stove and Poujoulat airtight chimney system supplied by House of Heat, including an airtightness plate connected to the airtight membrane, beneath an additional insulation sleeve to prevent cold bridging where the flue penetrates the envelope.

But Donn’s attention to environmental issues extended beyond energy. A 5,000 litre rainwater tank provides toilet water, and Donn plans to upgrade this in future to meet all the house’s water needs.

The house also has a Biorock gravity-based secondary wastewater treat system. Secondary treatment systems, which treat wastewater after it leaves a septic tank, typically use bacteria to further treat spillover. They normally use a pump to circulate water, but the Biorock unit can work off gravity alone because of the steep site.

Besides its environmental impact, good design is at the heart of Teach Maoldia. “The house has a lot of features that are normally associated with houses that have a much higher budget,” Donn says. “This was possible because I could spend the time to design and build every detail to a very high specification even if it meant doing it two or even three times.”

Most architects put public rooms downstairs — living room, dining room, kitchen — with the private bedrooms and bathrooms upstairs. But Donn took that layout and flipped it 90 degrees, creating two separate living spaces — a public one and private one — side by side, divided by a library with its own secret doors that houses Ita’s vast book collection and forms a vertical wall between the two parts of the house.

The other unusual design feature is the artistic imprinting on the central inner wall, which was also constructed with ICF. Donn removed the insulation here (which exposes the concrete and provides more thermal mass too) and used stones, grass, leaves, bark, fishing nets, bamboo and other items to create imprint on the wall. Other internal concrete walls in the house feature similar imprints with bamboo, sea shells, and the leaves of various tree species.

What has Donn learned from the experience of building to the passive house standard, albeit without the third party oversight and comfirmation that certification brings? He says designing a passive house in a rural environment — where there is no overshadowing from neighbouring buildings — is not difficult in itself. Teach Maoldia’s biggest glazed elements face east, but reaching the passive house standard was still quite achievable.

On the other hand, he says project managing a passive house build is not so easy — he reckons it is still difficult for general contractors and tradesmen to appreciate the level of detail needed.

“I think self builders like myself can do it and large professional building contractors with lots of resources can project manage passive houses successfully, but middle of the road builders will struggle unless they specialise,” he says.

“Sometimes I thought that I had bitten off more than I could chew as I struggled to build a house, let alone a passive house, but I am now incredibly happy that I set such a high target.”

Donn’s mother Ita and her husband Andrew fully moved into the house a few months ago. But in fact they had been living in the guest bedroom, which was completed first, since October. She says that even though there was no heating system during the winter, it was still much warmer in the new passive house than in the old cottage with its storage heaters and fireplace.

“It’s worked out absolutely stunning,” she says of her new home. “It’s hard to describe, it is just wonderful. It is just a beautiful place to live in.”

Selected project details

Client: Ita Molloy

Architect: Donn Ponnighaus

M & Engineer: Maurice Falvey

Civil & structural engineering: JJOS

Airtightness tester: Greenbuild

Insulated concrete formwork, foundations &

roof system: Passive Building Structures Ltd

Insulating concrete formwork supplier:Quad-Lock

Ground floor insulation: Kingspan

Windows & doors: Optiwin by Ambiwood

Heat pump & ventilation: Nilan Ireland

Chimney system:Poujoulat, supplied by House of Heat

Wood burning stove:Jydepjsen, supplied by House of Heat

Lighting: Lucas LED

Rainwater harvesting:Glenview Heating and Plumbing

Bathroom fittings: Ideal Bathrooms

Additional info

Building type: 184 sqm detached, two storey house on sloping site. Main entrance at rear on first floor.

Location: Castletownbere, Co Cork

Completion date: June 2014

Budget: £300,000

Passive house certification: not certified

Space heating demand (PHPP): 15 kWh/m2/yr

Heat load (PHPP): 11W/m2

Primary energy demand (PHPP):109 kWh/m2/yr

Airtightness (at 50 Pascals): 0.55 ACH or 0.662 m3/hr/m2

Building Energy Rating: pending

Thermal bridging: raft foundation insulated with 160mm polystyrene. Insulation brought up and around the toe of the raft foundation and joined with 160mm of external insulation on Quad-Lock ICF system. Internally 60mm of Kingspan polyurethane laid on top of raft foundation (underneath screed) and joined with the 60mm of internal Quad-Lock polystyrene. At roof level the concrete of the gables was kept down by 160mm and after concrete pouring the gap was filled with polystyrene. Quad-Lock ICF ties are made from plastic and are recessed into the polystyrene by 20mm. The roof is made from 220mm deep polystyrene panels. They are 1.2m wide with MS channels

running up the side. The channels are recessed 50mm so no steel is exposed on the outside of the roof. The internal plasterboard is glued on so no screws are used.

Ground floor: raft foundation insulated with Kingspan Aerobord EPS insulation – 160mm below the slab, and 60mm around the perimeter, with 60mm Kingspan polyurethane insulation above the slab. U-value: 0.136

Wall 1: slates, counter-battens (80mm), non-breathable roof underlay, ICF system (Quad-Lock) comprising 160mm polystyrene insulation on outside, 200mm reinforced

concrete (airtight layer), 60mm polystyrene; 12.5mm plasterboard internally. Wall 2: 8mm render, ICF system (Quad-Lock) comprising 160mm polystyrene insulation

on outside, 200mm reinforced concrete (airtight layer), 60mm polystyrene; 12.5mm plasterboard internally Roof: slates externally followed beneath by counter-battens (80mm), non-breathable roof underlay, 220mm deep polystyrene panels. (1.2m wide with MS channels running up the side), plasterboard (glued in factory). Panels taped to DPC embedded in top of ICF concrete walls. Foam filled between panels internally and externally. DPC on ridge taped to panels.

Windows: Optiwin Alu2Wood slim line windows. Triple-glazed aluminium clad timber windows. Overall U-value: 0.77.

Heating : underfloor heating linked to 3kW geothermal heat pump built into the Nilan Compact P exhaust air heat pump with heat recovery ventilation.

Wood stove: 3-5 kW Elegance Junior by Jydepjsen with a Poujoulat airtight chimney system.

Ventilation: Nilan Compact P JVP 3

Wastewater treatment: Biorock: Secondary waste treatment using gravity. LED lighting used throughout.