- Case Studies

- Posted

Botched Finglas upgrade

Ron and Collette Wardle started suffering ill health almost immediately after a sloppy energy upgrade. But reading a copy of Construct Ireland started a chain of events that led to the couple getting a brand new ventilation system — and seeing a marked improvement in their health.

About 30 years ago Ron and Collette Wardle found cracking in the walls of their 1950s terrace house in Finglas, north Dublin. An engineer told them that because the terrace was built with cement and concrete but without expansion joints, vertical cracking occurred every 30m or so along it.

A few years ago the Wardles decided to conceal the cracks and freshen up the house’s appearance with a new external finish. Their plasterer advised removing the existing sand-cement pebble-dash finish and replacing it with a much thinner acrylic render. But doing that left the house colder — the original thicker render had essentially been the houses’s only wall insulation, and it offered better protection from driving rain too.

The Wardles also had the house re-glazed a few years before that — but the installer did a shoddy job, leaving gaps around windows that created drafts. When the new render was applied a few years later the family had a colder, draftier house — and higher fuel bills. “We were cold to put it mildly,” Collette says. Older houses were often built with blocks and then wet plastered, inherently quite an airtight method of construction, so refurbishment can often make airtightness worse if proper care isn’t taken.

(left) filler pieces of timber sloppily fitted by a glazer when the house had new windows installed; (right)mould in the grouting between tiles in the bathroom

The Wardles decided to insulate as the winter of 2008 approached. They hired a contractor to dry-line the walls with insulated plasterboard, and to insulate the attic. But the couple quickly got the impression the builder had less experience than first indicated.

He was also a “sloppy” worker they said — rooms were covered with water and plaster up to five metres away from the walls while he worked. Ron decided to take matters into his own hands, taking time off work to help finish the plastering quicker.

But by the time the builder left, Ron and Collette were suffering from “dreadful” headaches, fatigue and hayfever-type symptoms. “We were exhausted and under the weather,” Collette says. “We woke up with hangovers having not gone to bed with any drink,” she says. Their conditions persisted.

About six months later — and after the couple tried but failed to find a solution — Ron came across an article in Construct Ireland by the architect Joseph Little that discussed potential health risks of improper dry-lining. Ron contacted him, and Joseph came out to look at the house. He spoke to the Wardles, took humidity and moisture readings and inspected the property.

Foil insulation was used to insulate the attic floor and ceiling but was applied contrary to building regulations

Little wrote in a report for the couple that, “from all accounts, [the builder] acted incompetently, disrespectfully and unethically.” The builder’s branding emphasised his green credentials, but Little points out that a builder first needs to be competent at the basics of his trade before even thinking about energy and environmental issues.

In his report, Little said the foil insulation in the attic was applied contrary to the building regulations. He also noted: “I could not sense damp or mould, except for the bathroom where mould in grouting and sills was visible. The shower hadn’t been used that day and relative humidity was about the same as elsewhere in the house, about 48 RH. The attic was higher at 54.3 RH. Moisture content of items in bathroom which had mould was slightly higher than usual (17% in timber, 0.55% in grout) but far below chronic levels.”

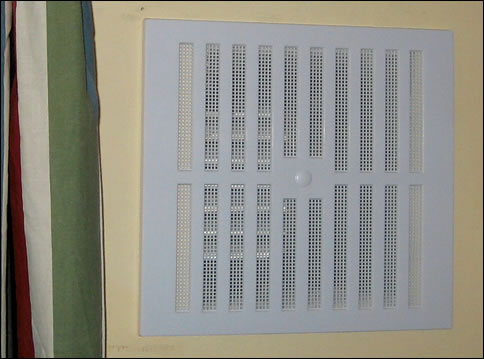

Ron himself knocked a large hole-in-the-wall vent in the master bedroom. “There appears to be no other vent in the house,” Little wrote. “The house is therefore well below building regulations standards for background ventilation and by this alone may be considered an unhealthy environment.”

Little reckons that if there were contaminants — such as volatile organic compounds and mould spores — in the air before refurbishment work was carried out, the unintended air leakage around the windows would have helped to dilute and dissipate these. “Since these gaps were blocked [when the house was renovated] in November 2008 this kind of dilution is clearly impeded,” he wrote.

The sudden health issues the Wardles suffered right after the upgrade suggests high levels of dust and wet plaster in the air at the time, coupled with poor ventilation, could have been a cause. But as the quality of air gradually improved over time, it’s less clear why they continued to suffer ill health — after all, plenty of Irish homes have poor indoor air quality without the same problems. It may simply have been that the indoor environment was still not healthy enough to enable recovery.

The large hole-in-the-wall vent created by Ron Wardle in an attempt to improve indoor air quality

Joseph Little recommended the Wardles install a passive-stack, demand controlled ventilation system to improve indoor air quality. Aereco supplied, and Durkan Ecofix installed, two passive stack flues from the ‘wet’ rooms — one from the kitchen downstairs to the roof and another from the upstairs bathroom to the roof. The height of the flue, the wind speed and the temperature difference between inside and out combine to ‘suck’ air up and out of the wet rooms — this is the passive stack effect.

Demand controlled vents feature in the kitchen and bathroom — these automatically open as relative humidity gets higher, allowing more air into the flue and starting the stack effect. Between 35% and 70% relative humidity, the vents open gradually as the humidity rises. Above 70% they’re permanently open, while below 35% they’re only slightly open to allow for background ventilation.

Humidity is an ideal indicator for indoor air quality because the production of moisture is closely associated with occupancy: as people breathe, sweat, cook and shower, humidity goes up. In wet rooms where air is extracted the vents mainly respond to the direct production of moisture through activities such as cooking and showering. In living spaces such as bedrooms and living rooms, the production of water vapour from breathing [which coincides with a rise in CO2] triggers the inlets to let met more fresh air in.

The humidity sensors are essentially a nylon strip that expands and contracts based on humidity, opening and closing the vent accordingly. Aereco’s Simon Jones says the flap works “very accurately and consistently”, and that the technology was invented nearly 30 years ago by Aereco and has been installed in nearly 3.2 million dwellings to date. The company offers a 30 year guarantee on the sensor.

But did the Aereco system make a difference for the Wardles? Collette says yes, that their conditions started to improve a week to ten days after it went in, and that they “absolutely” noticed an improvement in air quality. “We’re so much better than we were,” she says.”As the gradual air came back in we began to breathe properly.”

Of course the Wardles’ story is only anecdotal — there’s no medical evidence that the renovation caused their health problems, we just know that they started right after the upgrade work. And of course neither Construct Ireland, Joseph Little or Simon Jones claim to have medical expertise.

But there’s still an important lesson in the Wardles’ story. Aereco’s Simon Jones stresses that in the current rush to energy upgrade buildings, ventilation is in danger of being forgotten — and the consequences are potentially serious. He’s become accustomed to hearing about householders who consider it an optional extra when renovating. “Our answer is that if you can’t afford to have ventilation, you can’t afford to have the work done,” he says. “It’s not an optional extra — fresh air is something you need.”

Related items

-

Lung disease patient: Zehnder MVHR “the best thing I’ve ever had”

Lung disease patient: Zehnder MVHR “the best thing I’ve ever had” -

Awaab Ishak’s death shows that building physics are a life and death matter

-

It's a lovely house to live in now

It's a lovely house to live in now -

World’s first passive house hospital completed in Frankfurt

World’s first passive house hospital completed in Frankfurt -

Measuring humidity, the old school way

Measuring humidity, the old school way -

Poorly ventilated retrofits can double radon retrofit risk, study finds

Poorly ventilated retrofits can double radon retrofit risk, study finds -

Radon in passive houses

Radon in passive houses -

NuWave Sensors launches CO2 monitor for schools

NuWave Sensors launches CO2 monitor for schools -

NHS to get its first passive building

NHS to get its first passive building -

New report questions long-held MVHR assumptions

New report questions long-held MVHR assumptions -

Humidification can help prevent infection — VentHeat

Humidification can help prevent infection — VentHeat -

Doctor's orders - The complex relationship between energy retrofits and human health

Doctor's orders - The complex relationship between energy retrofits and human health