- Opinion

- Posted

Saving Plan

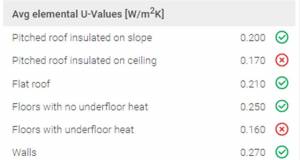

Fingal County Council have clearly shown a laudable commitment to innovation by introducing a mandatory planning requirement for seven areas that all new developments reduce energy use and C02 emissions relating to space & water heating to 60% below Building Regulations requirements, with 30% of space & water heating coming from renewable energy sources. Wicklow County Council have recently followed suit and several other local authorities are looking to follow in their footsteps. Many councils may fear that introducing standards of this kind would add a cost burden that would stifle development and make new homes unaffordable for their constituents. Not so, argues Jeff Colley. Could it really be that this won't add any cost for developers or house buyers?

When Fingal County Council took the landmark decision of setting strong sustainable building requirements into the Cappagh Local Area Plan in October of last year, the arguments for and against such a progressive initiative started rattling around in my brain. In the process of writing about the story as it has continued to unfold, I have discussed the minutiae of the policy Fingal introduced with an exhaustively diverse group of people who could bring their experience to the various implications that arose from setting such a standard.

Coming up with a robust understanding of the various issues has involved speaking with everyone from developers with land in areas where these standards have been introduced, to economists, to planners, to architects, engineers & product suppliers with experience and know-how of how to fulfil requirements of this nature. Although the social, environmental and long term cost benefits of this approach are easy enough to understand, the key issue in most people's minds is expense. Would it cost too much and discourage developers from building, or force property prices even higher?

The natural assumption to make is that demanding considerably better energy performance standards would send construction costs vertical, and that developers, being bottom-line oriented, would balk at the idea of any extra outlay. The other fear is that if developers have to spend extra, they'll pass on that extra cost, and a little extra for their trouble, to the long-suffering house buyer. There is also an assumption that many developers will only do the very least they can get away with, to keep profits as high as possible. But is this true?

The way the situation has evolved in Ireland during the property boom over the last decade or so, there surely is at least a grain of truth in that. However, there are a number of factors that have caused this, to my mind, and they are destined to change. To state the very obvious, the Irish property market has been a seller’s market for some time. Irish people have looked at what has happened to house prices during this meteoric rise, and assumed that the graph will keep on rising. This creates panic, and people buy property before prices rise more.

Every once in a while, some think-tank or other pops up in the media and warns of a property market slowdown or—worse still—crash, drawing comparisons between trends in Ireland and other markets that suddenly lost their buoyancy. To deal with any wobbles in consumer-confidence, a government figure might say “if you’d listened to them a few years ago look how much you would have lost out on!”, or alternatively a bank economist might announce further dramatic increases in property prices and reassure people that there’s still plenty of room for growth, all the while cranking up the percentages of mortgages they’re prepared to offer, till they’re eventually lending the whole house price and paying the mortgage holder a deposit! All of which means that homebuyers, who believe what they’ve been told, buy houses, pushing prices up further again.

In this seller’s market, people don’t tend to ask the questions they should. They may prefer a more sustainable home if given the option, but in a seller’s market they haven’t had that luxury. The onus has been on getting your hands on a property no matter how badly built it may be, and then trying to move up the property ladder. Conversely, the self-build market, where the homebuyer is the specifier, offers some insight into what people want from a home, as they have the power to choose. It’s common knowledge in the sustainable building industry that the self-build market has been key to the growth of the sector.

Similarly revealing is the response to the Greener Homes Scheme, which offers grant funding for the domestic installation of renewable energy technologies. The scheme was announced on 26 March this year, and by 26 June, Sustainable Energy Ireland (SEI) had approved 4,000 grant applications—well above what they had anticipated. A couple of years ago, before energy prices started to rise, and before mandatory energy ratings for buildings were looming on the horizon, there was no real incentive for developers to build sustainably. Why would they? They could sell poorly built houses that just scraped through theoretical compliance with the thermal performance requirements of the Building Regulations—and almost certainly did not actually comply due to poor workmanship on site. I’ve spoken to developers who say they would not spend above the bare minimum on construction costs purely because if they intended to spend more to achieve better performance, another developer could outbid them on the land, and cut corners when it came to building the development. Therefore this encourages land prices to rise, forcing developers to drop construction standards to stay competitive. This is very much a symptom of a market where the only regulation is to demonstrate—even just on paper—minimum compliance with poor building standards.

If on the other hand, as the economist Richard Douthwaite explained in Construct Ireland Issue 12 Volume 2, a local authority such as Fingal County Council raises the bar regarding sustainable building standards, when developers are bidding for the land they will work out how much extra they think they need to spend to meet those standards, and subtract it from what they’re prepared to pay for the land. The developer who bids highest for the land is the developer who works out the cheapest way to meet those standards, as before. The onus is on the local authority to ensure they don’t cut corners—a problem that is not helped by our building culture of self-certification.

As Douthwaite pointed out—and every developer I have discussed this principle with agrees that this is correct—if there is a mandatory higher standard that everyone must meet in a given area, it won’t cost the developer any more, once land purchase and construction costs are added up. Instead it takes some of the sting out of grossly inflated land prices, and allows developers to spend more on build costs, which ultimately benefits the buyer in terms of comfort, lower running costs and quality of life. The point essentially here is that the total cost—the combination of land and construction costs—does not change, but rather the ratio between the two shifts so that land costs decrease and construction costs increase. The only loser is the landowner, who has probably been doing too well in any event.

There is no comparison between the costs for a developer voluntarily building to the standard that Fingal have put forward and the costs for a developer having to build to these standards as a planning requirement. In the former case, the developer can be undercut by other developers prepared to spend less on construction. In the latter case, the developer who has worked out how to get to the standard most cost-effectively can bid more, and therefore build. It follows that, by introducing higher standards, the local authority is actually helping to make sustainable building more and more cost-effective, by getting developers on board, with the developers’ skill at lowering costs combined with economies of scale, bringing the cost of sustainable building down. In Fingal alone, the volume of building expected to be built in the seven areas where mandatory sustainable building requirements exist, is roughly between 11,400 -12,400 units. Even at these sorts of volumes, it makes sense for manufacturers to develop products tailor-made to meet this standard. I urge any local authority with concerns about setting similar standards because of the extra effort for the construction industry to learn how to meet the standards in the short term, to compare the length of time it takes to design and construct a building with the length of time that building will be in use—perhaps for 100-150 years. The hassle and extra expense of living in a thermally inefficient building as energy prices rise, and the extra cost and hassle of trying to upgrade the building’s energy performance later on make any short-term construction industry hassle seen utterly insignificant in comparison.

Not only will setting high sustainable building standards not cost the developer more, it follows that it will not add to the price of property for buyers—unless the market is prepared to pay for it. In an address to an All Party Oireachtas Committee on Private Property in 2004, Thomas Dunne, Head of the School of Real Estate and Construction Economics at DIT explained how this works:

In any given period, the addition of new buildings to the housing stock will be very small in proportion to that stock. The value of new buildings will therefore be influenced to a substantial degree by the stock of existing buildings. Prices will be set primarily by demand for the existing stock and not by the flow of new buildings. In the housing market, builders are price-takers and will sell their product at a price determined by the market and not by the value of the land and the cost of construction.

The Society of Chartered Surveyors in its submission to the Committee stated that:

House prices are fundamentally a function of the balance between supply and demand and the economic capacity of purchasers, coupled with market expectations on interest rate predictions.

Returning to the issue of construction costs—which as we have established don’t impact on the development costs for a mandatory standard such as has been applied by Fingal—it’s important to recognise some of the factors that have until now distorted the costs of applying sustainable building standards. The SEI House of Tomorrow Programme is a grant-funding initiative administered by SEI since 2001 geared to encourage developers to improve energy performance, reduce C02 emissions and boost the uptake of innovative technologies ranging from renewable energy systems to heat recovery ventilation to condensing boilers.

Developers who design buildings to consume 40% less energy for space and water heating than the Building Regulations minimum standards, whilst also incorporating innovative energy saving/low CO2 technologies, can be awarded €8,000 per dwelling, with an upper limit of 50 dwellings per scheme (the criteria and levels of grant funding available through House of Tomorrow have changed over time). However, for each €8,000 sum the developer must have spent €16,000 on bringing each dwelling up to that standard. Whilst House of Tomorrow has latterly been an invaluable tool in encouraging developers to build more sustainably, there is little doubt that it can give the impression that building to that standard costs more than it otherwise might.

A very encouraging indication of how far the industry has moved on since House of Tomorrow’s very slow initial progress 5 years ago was revealed recently by Programme Manager Ivan Sproule.

“Intense interest is being shown by private developers in SEI’s House of Tomorrow programme at present. It is clear that there is a growing appetite and capacity among progressive builders to apply more ambitious energy performance standards in their developments”, he states. “Indeed, SEI has been approached by a number of developers who, without funding support, are interested in adopting the House of Tomorrow standards of energy performance, in having that performance verified by SEI, and in being branded by SEI accordingly.”

Clearly, times are changing. Arguably, given that House of Tomorrow has successfully managed to bring developers towards sustainable building up to a point, the scheme should be revised to impose more ambitious targets. Although many projects apparently comfortably exceed the scheme’s requirements, when local authorities are starting to introduce mandatory rather than voluntary standards which are more innovative in terms of energy and CO2 reduction and sheer scale, it suggests House of Tomorrow must up its standards or risk no longer living up to its billing.

Dr. Wolfgang Feist, head of the hugely influential Passive House Institute in Germany draws from unsurpassed experience with which he can assess the viability of the Fingal sustainable building requirements. The institute developed the Passive House standard, and in so doing have created a building philosophy that is so energy efficient that no conventional heating system is required. Based on concerns such as orientation, highly insulated and airtight structure with heat recovery ventilation combining renewables for water heating, a Passive House has an overall actual space and water heating requirement of less than 40kWh/m2/year. Roughly 7,000 have been built to date in Europe, many of which were built when energy prices were still relatively cheap. According to Feist, achieving a less ambitious requirement of 60% lower water and space heating than Irish Building Regulations combined with 30% renewables should not be a problem in Ireland.

“The Irish climate is much less challenging for energy efficient construction than the Central European [climate]. It is not that cold during the winter and is far less hot in the summer. “Therefore the efforts [involved in meeting] good energy efficient standards in Ireland will be even less than in Germany. In Germany the state of the art (that is passive houses) has been proven to be affordable: The extra investment compared to “normal” new houses is in the range of 6 to 10%, and this pays back [through] the energy costs saved”.

Not to sound like a broken record, but even those relatively low extra construction costs for an excellent built result would not add to the total development cost of buildings if the standard was mandatory.

Another major factor that will help the Irish construction and property industry to move away from a culture of just achieving paper compliance with poor minimum requirements of Part L of the Building Regulations exists in the introduction of mandatory Building Energy Ratings at point of transaction, under the Energy Performance of Buildings Directive. With high energy prices sharpening people’s focus, and a degree of transparency becoming available to anyone looking to buy or lease property, the market will start to demand high-rated buildings. Since the start of July building designers have been obliged to use the new Dwelling Energy Assessment Procedure software to calculate energy performance of all new homes starting the planning process. This should very quickly cause designers and product suppliers to start looking at how well they can make building perform rather than how little they need to do to appear to comply with poor minimum standards. This is an enormously positive development for local authorities looking at adopting ambitious sustainable building requirements in their own counties, as for the first time in our history the construction industry will have the incentive of an A rating to aspire to. In this context, local authorities who take a leaf out of Fingal’s book by setting a mandatory high standard will be effectively ensuring that new homes achieve high energy ratings at no extra cost.

Related items

-

The world energy crisis 2022

The world energy crisis 2022 -

When is an A-rated home really A-rated?

When is an A-rated home really A-rated? -

Grant heat pumps at centre of NI energy transition project

Grant heat pumps at centre of NI energy transition project -

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries

SEAI Energy Awards 2020 open for entries -

Software errors create false NZEB compliance picture

Software errors create false NZEB compliance picture -

WWHR an easy & costeffective route to Part L compliance — Showersave

WWHR an easy & costeffective route to Part L compliance — Showersave -

The Jodrell Bank grand challenge

The Jodrell Bank grand challenge -

'Achieving NZEB' event in Cork this Thursday

'Achieving NZEB' event in Cork this Thursday -

The slow, heavy gears of deep retrofit start to turn

The slow, heavy gears of deep retrofit start to turn -

Architect returns to roots with A1 rated 'house of the people'

Architect returns to roots with A1 rated 'house of the people' -

Use all your solar electricity at home rather than export it — Warik Energy

Use all your solar electricity at home rather than export it — Warik Energy -

SEAI Energy Show to take place on 6 & 7 April

SEAI Energy Show to take place on 6 & 7 April