- Social Housing

- Posted

Sociable Housing

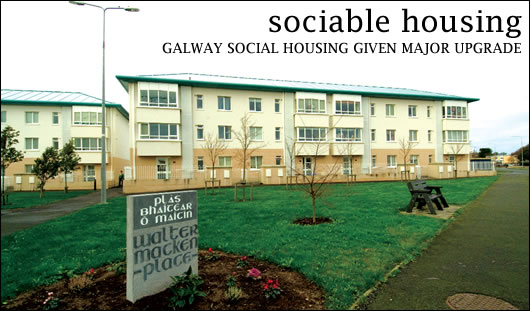

Lenny Antonelli visited a recently refurbished complex of social housing flats in Galway city that has combined excellence in urban regeneration with energy efficiency and major strides towards sustainability

Think about social housing regeneration projects, and it’s likely the first thing that will come to mind is Ballymun. The plans to revitalise and refurbish the Dublin district have received considerable attention in the media, with coverage focused not just on the demolition of the existing tower blocks, but on the plans for a major revitalisation of the entire area and on the high environmental standards likely to be applied. In Galway, however, an award-winning social housing refurbishment scheme has already set high standards in terms of both urban renewal and energy efficiency.

Early in 2006, the refurbishment of six blocks of social accommodation flats at Walter Macken Place in Mervue, on the east side of the city, was completed. In the six months after work was finished, Galway Energy Agency, a subsidiary of Galway City Council, monitored the energy use in four of the apartments to understand the effects the renovations had on energy demand.

The refurbishment work included upgrading the insulation spec of the buildings, installing insulated pitched roofing, switching to gas heating in two thirds of the flats, and installing low energy lighting. The buildings were also given a much-needed fresh coat of paint, and the surrounding area was landscaped. “They were known as the Walter Macken flats before, but people are calling them the Walter Macken apartments now because of the modernisation and difference in style”, says Peter Keavney of Galway Energy Agency. The refurbishment was principally financed by the Department of the Environment under the National Development Plan, but Sustainable Energy Ireland, under its House of Tomorrow program, provided approximately e5,000 each towards the energy efficiency measures for 48 of the 96 units.

Talking to residents, you begin to realise just how bad things were before. “It was desperate”, says Joe Geoghegan, who has been living at Walter Macken Place for seven years and was chairman of the residents’ committee during the refurbishment period. “The damp and mildew were terrible before. Clothes were covered in mildew. It was cold inside. There was fungus growing on the wall behind my couch.” When I ask him what colour the buildings were before they were painted, he describes them as having been “the colour of dirty concrete”.

Refurbishment began in the summer of 2004. Providing proper insulation was one of the key priorities. The existing wall cavity was lined with 50mm of expanded polystyrene (EPS) platinum insulation and pump-filled with 70mm of EPS bonded bead, provided by EcoWise. A 35mm layer of external plaster cladding was also added, resulting in an efficient three-layer insulation system. The walls of the unheated stairwells were also dry-lined internally.

Prior to refurbishment, the flats were heated by what Peter Keavney describes as a “very poorly efficient underfloor electric heating system, with no insulation.” On the suggestion of Galway Energy Agency, Galway City Council chose to heat 48 of the units with natural gas, which produces almost 30 per cent less CO2 emissions than oil, and over 50 per cent less than coal. Gas-condensing boilers were installed in all flats on the middle and upper floors. However, there was no Bord Gáis network in the area when refurbishment began. “We used bulk storage on site and switched over to natural gas when it became available. We don’t like to depend on anybody”, says Peter Keavney. The ground floors of the six apartment blocks were left with electrical storage heating however, as many of the older people living on this level had expressed concerns about the safety of gas heating systems. “I think that fear is mainly down to lack of information from the gas board,” Joe Geoghegan, who previously lived in a ground floor flat, but now lives on the top floor, says. The ground floor units are about half of the size of those on the first and second floors, so approximately two thirds of the complex is now heated with natural gas.

The buildings were originally constructed with flat roofs that, unusually for their construction date of 1970, incorporated a 50mm layer of corkboard underneath the asphalt layers, providing a reasonable degree of insulation compared to most developments from that era. However, according to residents, some roofs had serious problems with leaks. During refurbishment, new pitched roofs composed of Kingspan ‘sandwich’ panels were installed incorporating 60mm of polyurethane insulation, while 200mm of fibre glass quilt insulation was also laid on top of the previous flat roof surface.

Double-glazed uPVC windows were installed throughout the buildings, replacing the previous single-glazed panels and steel frames, which, according to Joe Geoghegan, “used to just let the air right in. There was no difference between the window being open or closed.” PVC, however, is not the most environmentally sound of materials as its manufacturing process is known to generate dioxins that are damaging to both the environment and human health.

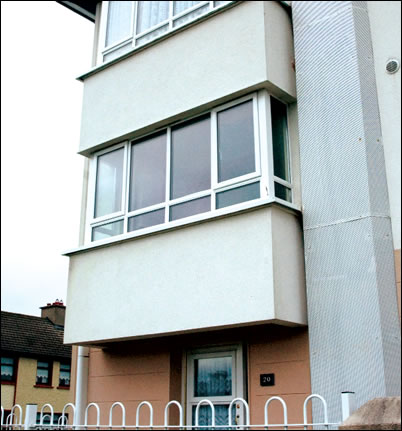

What used to be first and second floor balconies has now been enclosed and converted into extra living space

Small outdoor balconies that were previously separated from the interior only by a single sheet of glass were fully enclosed, adding more space to the kitchens in each flat. “We enclosed the entire balcony in a fully glazed window system. We also provided insulation under and around the concrete balcony area and over the window. It improved the appearance of the blocks immensely”, says Billy Dunne, Galway City Council’s main engineer on the project. The existing concrete balcony slabs were also upgraded to provide the same thermal performance as a floor - in this case a U-value of 0.25 W/m2K.

Low energy CFL light bulbs were installed in the stairwells and in the flats themselves, though Joe Geoghegan told Construct Ireland that those in his stairwell were continually burning out after a couple of weeks. This problem, however, appears to be isolated. The surrounding grounds were also landscaped as part of the project. “We did a landscaping project on the grounds to provide some semi private space, because before they were essentially just blocks of flats in a field. Now there are trees planted, seating and pathways,” Billy Dunne says.

Data collected by Galway Energy Agency, in the five months after refurbishment was completed in apartments in two of the blocks, indicates impressive reductions in energy consumption. Four apartments were selected and monitored. Two of these were in the very middle of their respective buildings, with just two side walls exposed to the outside. The other two apartments were corner apartments on the top floors of their buildings, with two additional surfaces exposed. Intuitively, it was predicted that the middle apartments would have a lower energy demand for heating. As well as this, two of the four monitored apartments – one middle, one top corner – were chosen from a building that is exposed to the dominant south westerly wind, while the other two apartments were selected from a more sheltered building. It was also anticipated that the flats from the more exposed building would require more energy for heating. These predictions, however, were not borne out in the actual assessment (see Table 1).

As the figures show, the flats from the sheltered block actually used more energy, while one ‘middle’ flat (C) consumed more than a ‘top corner’ flat (B). In its assessment report, Galway Energy Agency notes that “B, C and D are overheated”, while A is “not heated to optimum internal temperatures”. In essence, the personal habits of tenants are the reason behind the discrepancies. When corrected to take weather conditions into account, the heat energy ratings (a measure of how much heat is required to maintain comfortable living conditions and heat hot water) of the four monitored apartments ranged from 50.6 kWh/m2/yr to 170.7 kWkh/m2/yr. Although three of the four apartments that were monitored after refurbishment was completed consumed more energy than predicted, the figures still represent a significant drop from the HER it was calculated the flats had before refurbishment began – 546.86kWh/m2/year.

Even though the average increase in consumption over what was predicated is 22.6 per cent, this still means the estimated average overall reduction in energy use is an impressive 65 per cent. This figure, however, is likely to be an overestimation, as the HER calculated for pre-refurbishment conditions presumes that each flat is heated throughout, which would have been unlikely in many instances due to the expense of heating every room of such poorly insulated properties.

There are a number of possible reasons that energy consumption in the apartments monitored was greater than expected. Galway Energy Agency says this was probably a result of the need for extra heating to dry out a building after renovation. As well as this, the cost of natural gas after work was completed was about 25 per cent less than at present, making overuse more likely. And although boiler operation manuals were given to all occupants, this may not have been enough to ensure a good working knowledge of controls and efficient use. In its monitoring report, Galway Energy Agency stated that ideally, boiler manufacturers or suppliers should be engaged to provide a working demonstration to residents.

Data recorded in two of the selected apartments shows just how big a role the new insulation now plays in keeping the flats warm. In one apartment which was heated to 20oc, temperatures dropped by 5oc over 14 hours after the heating was switched off, despite outdoor temperatures that were as low as 4oc. Another apartment, also heated to 20oc, fell by just 6oc over 28 hours, even though outdoor temperatures dropped to 2.5oc.

The new standards of energy performance are a testament to the exacting standards Galway Energy Agency aimed for. “If we’re doing refurbishment, we should always target the new build requirements”, Peter Keavney says, referring to Part L of the 2005 building regulations, which were in operation when the project began. They hit that target, and indeed, the U-values they achieved are impressive for a refurbishment project (see table 2).

“The refurbishment has made a huge difference,” Joe Geoghegan says. “The first thing you strikes you, and I even noticed it when I just came in, is that I haven’t had the heat on for the last two days and it’s still warm in here. With the insulation, you really don’t need to. Because if you have it on for an hour or two hours, it’ll keep warm.”

Even though his flat lost a balcony, he’s pleased with the extra space that has been added to his kitchen. “It’s given us more space in the kitchen. When they knocked out the wall into the balcony, they took full advantage of the light potential. Even on a dark morning the kitchen is well it up.”

From the outset, residents played a key role in the project and were listed as official partners for the development. “We held a number of public meetings to explain things to residents, and we got a residents committee together to liaise with on any issues that arose. We took on board any suggestions they might have, and assessed their concerns. We also put into the developer’s contract that he employ someone directly that would liaise with tenants on the site”, Billy Dunne says. Joe Geoghegan was pleased with the consultation: “We had a fair few meetings in city hall with engineers and councillors. I think that’s why everybody is happy enough up here, because we had our input.” The project received a certificate of excellence in urban renewal from the City Neighbourhoods competition in 2005.

The refurbishment of Walter Macken Place was not, strictly speaking, at the cutting edge of green building due to budgetary constraints (there was no money available for renewables). However, it is a very important project in a number of regards. Firstly, more refurbishment of our housing stock is urgently needed. While the regulations for new build announced last year by the Department of the Environment represent a major step in the right direction, in a slowing housing market they will only have an incremental impact on our energy consumption and carbon emissions unless they are backed up by some sort of national program to retrofit much of our existing housing stock to significantly higher energy standards. Peter Keavney believes that the Walter Macken refurbishment can serve as a useful template for other projects: “We’ve been contacted by other local authorities, and this experience has helped us to put together guidelines for others that are looking to do refurbishment.” This project demonstrates that value-for-money, quality refurbishment is possible, which is reassuring to know, particularly considering the environmental impact of refurbishment is considerably lower than the energy intensive process of knocking and rebuilding.

In addition to this, the refurbishment of social housing projects to higher energy standards is crucial to alleviating fuel poverty, which is defined simply by the charity Energy Action as the inability to pay for adequate heating. Charlie Roarty, Energy Action’s general manager, told Construct Ireland that Ireland has one of the highest rates of fuel poverty in northern Europe. Thankfully, this is now being tackled by a Department of the Environment scheme to ensure all social housing has central heating, loft insulation and draft-proof doors and windows.

And, perhaps most importantly, in older social housing estates that have often been built to poor standards, it also provides a template for making a real difference in the lives of residents. As Joe Geoghegan says: “I love it here. I wouldn’t live anywhere else.”

The value for local authorities in taking such an approach is summed up by Joe McGrath, Galway City Manager. “The time scales for building new social housing are fairly lengthy in relation to site acquisition, planning, and tendering for construction” he says. “Refurbishment would appear to be a very good option, including energy upgrades beyond the current building regulations. Improving energy measures beyond the current regulations increases the asset value of the city council’s housing portfolio”.

- Articles

- social housing

- Sociable Housing

- Galway Energy Agency

- urban regeneration

- Council Estate

- energy efficiency

- house of tomorrow

Related items

-

Energising Efficiency

-

Bonny in Clyde

Bonny in Clyde -

From Nero to zero

From Nero to zero -

Measure everything

Measure everything -

Renfrewshire aims for 3,500 whole-house deep retrofits

Renfrewshire aims for 3,500 whole-house deep retrofits -

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced

Major new grants for retrofit & insulation announced -

Welsh social housing to embrace passive house, timber & life cycle assessment

Welsh social housing to embrace passive house, timber & life cycle assessment -

International passive house conference kicks off

International passive house conference kicks off -

Ecocel on site with 56 homes in Cork

Ecocel on site with 56 homes in Cork -

Senior college

Senior college -

COP 26 & the future of the Glasgow tenements

COP 26 & the future of the Glasgow tenements -

Is affordable housing a policy blind spot?

Is affordable housing a policy blind spot?