- New build

- Posted

All bales, no bills

In the classic story of the three little pigs, the big bad wolf may have blown down the first little piggy’s house of straw with consummate ease — but he wasn’t reckoning with this pioneering, energy bill-shredding Suffolk project, the UK’s first load-bearing straw bale passive house

Click here for project specs and suppliers

Building type: Two-storey load-bearing straw bale house

Location: Onehouse, Suffolk

Completed: September 2015

Standard: Passive house classic certified

£115 profit Energy bill: all heating & electricity (including solar feed-in tariff)

Dave Howorth puts his decision to self-build the UK’s first load-bearing straw bale passive house down to “a moment of madness”. His original intentions had been less ambitious: he had just wanted to satisfy his green instincts by adding a few photovoltaic panels to his old house in Hitchin, Hertfordshire.

But he ended up in a challenging self-build project that required him to learn straw bale construction, defeat planning objectors, and then acquire the skills of a carpenter, an electrician and a plumber on the job.

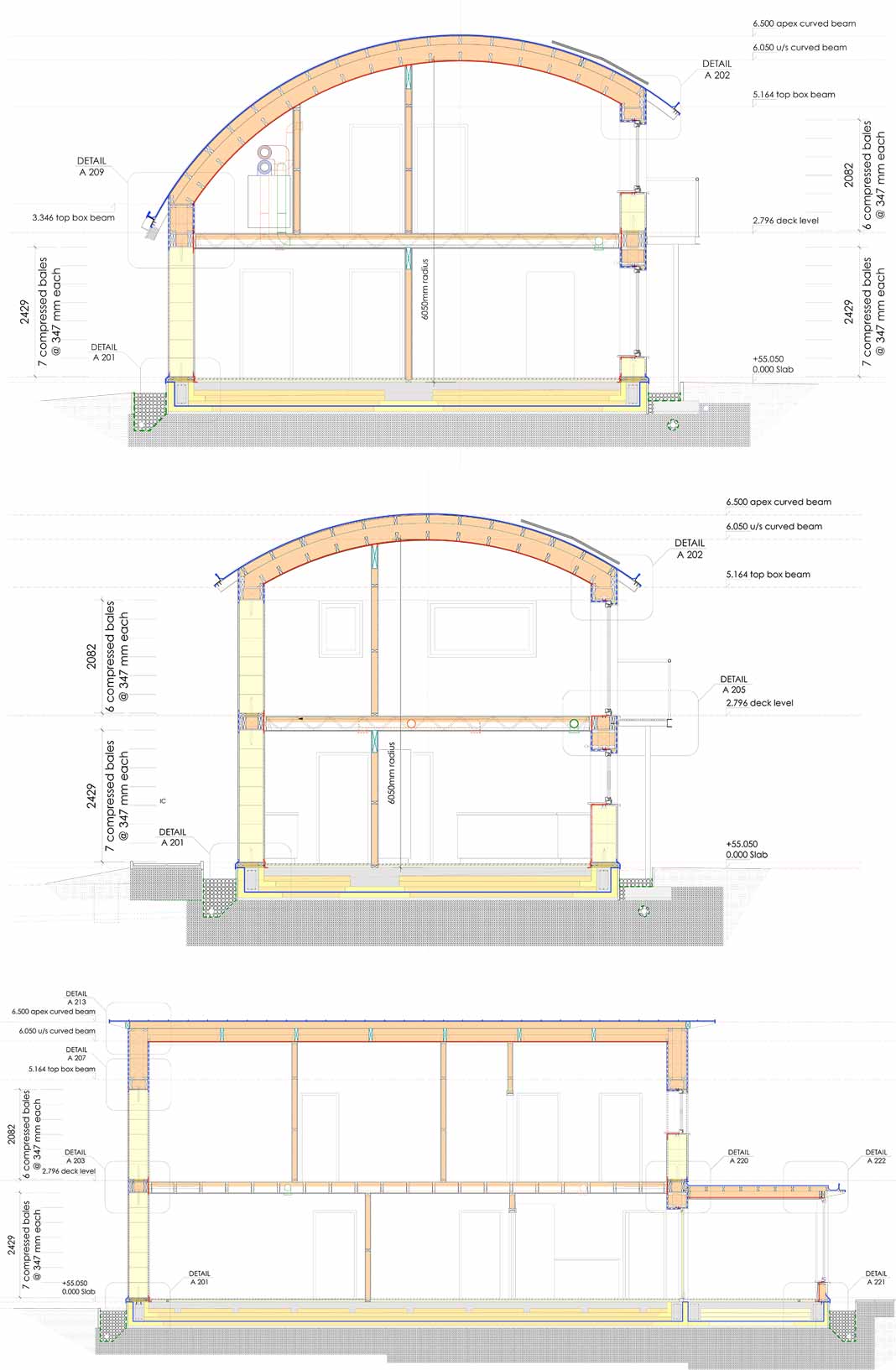

Meanwhile, the structural engineer faced challenges of his own, partly because of the lack of information available about passive houses, but mainly because the curved roof presented technical difficulties.

At that point, I had to become a super apprentice of everything: carpentry, plumbing and electrics.

So when Dave and his wife Mabel eventually moved into Haven Cottage, in the Suffolk village of Onehouse, in June 2015, it was the culmination of a dream that had taken six years to fulfil. Howorth first became interested in straw bale building back in 2009 when he took a course with the UK’s leading expert, Barbara Jones, in Lincolnshire, and visited several straw bale buildings around the UK.

The couple then spent three years hunting for a suitable site before finding the Suffolk plot in 2012. Even then, it was not a straightforward matter to go ahead and build the house they wanted. Planning permission was opposed by the parish council, and it took a further three years to design and self-build the house.

Despite the long gestation, Howorth says it was worth it. The house has achieved passive house certification, and is quiet and warm within, he says. The couple appreciate the natural feel and low heating bills. “I love the simplicity and economy of straw bale building and the DIY element of the build. I’d do it all over again,” he says.

Howorth’s interest in straw bale building was sparked when he read about the ideas of Barbara Jones, whose Straw Works consultancy offers practical courses in straw bale building. Groups of volunteers turn up at a self-build site and help the owner install the bales while Jones, or another qualified tutor, supervises the work.

Equipped with their new skills, the volunteers then go off to carry out their own self-builds. Having attended one of the Barbara Jones courses in 2009, Howorth became part of the straw bale building community and knew he would be able to call on volunteers to help construct his house when the moment came.

The couple bought their plot with planning permission attached in March 2012, but the existing architectural plans were unsuitable.

So they asked Andrew Goodman of Hertfordshire-based Good Architecture to provide a new design for a four-bed passive house using 450mm thick compacted bales.

“The site had permission for an unimaginative chalet bungalow, but it wouldn’t have achieved the passive house standard and didn’t lend itself to straw bale construction,” says Goodman. “We created a completely different two-storey design with a curved ‘Dutch Barn’ style roof in keeping with the Suffolk vernacular.”

Architectural assistant Abbie Davies did a lot of the initial design work while studying sustainable architecture at the Centre for Alternative Technology in Wales. Davies argued that the straw bales could be used for conventional load-bearing (see ‘How the straw bale walls were built’).

“We designed it so all the external walls and roof could be built, then plastered on the inside,” says Goodman. “We could then do an initial air test before the internal partitions were constructed. That way we could see if there were any holes in the walls and repair them. But as it turns out there weren’t any.”

The uniqueness of the project provided technical challenges for superstructure engineer Paul Rose, who was brought in because he had previously worked on three straw bale load-bearing houses. At the time, he wasn’t even aware that Dave and Mabel wanted to achieve the passive house standard.

“One of the biggest issues with straw bale is the lack of information available,” Rose says. “But we’ve done a few now and learned on the job. A bigger challenge with this project was the curved roof. We had to make sure the lateral forces at eaves level weren’t so great that they pushed the straw bales over.

“The roof had to be stiff enough so the arched members didn’t push sideways to any great degree and push the walls over. I’ve only designed two or three roofs like that in my career,” he says, adding that “the fact it was straw bale made it tricky and interesting”. One of Rose’s solutions involved adding a horizontal beam to support the curved beams that create the roof.

The initial conceptual designs were completed in November 2012 and submitted for planning permission, which was opposed by Onehouse Parish Council, who argued because the home was next to a Grade-II listed cottage, its contemporary design was “totally out of keeping with the character and the appearance of the area”.

Fortunately for Dave and Mabel, Mid-Suffolk’s conservation officer said it would not have any significant harmful impact, and planning permission was granted.

The architects were then able to get to work on more detailed designs, which were completed in stages between August 2013 and January 2014. “Although the design is quite contemporary, finishing straw bale in lime render is ideal in relation to nearby listed buildings,” says Goodman. “We haven’t used straw in the roof, but we have in the walls. We drew elevations in nice straight lines with plumb corners, but it’s all fairly wobbly [looking] because it follows where the bales go. So whilst the design is quite contemporary in some respects, it’s softened by the straw bale element.”

I love the simplicity and economy of straw bale building and the DIY element of the build. I’d do it all over again.

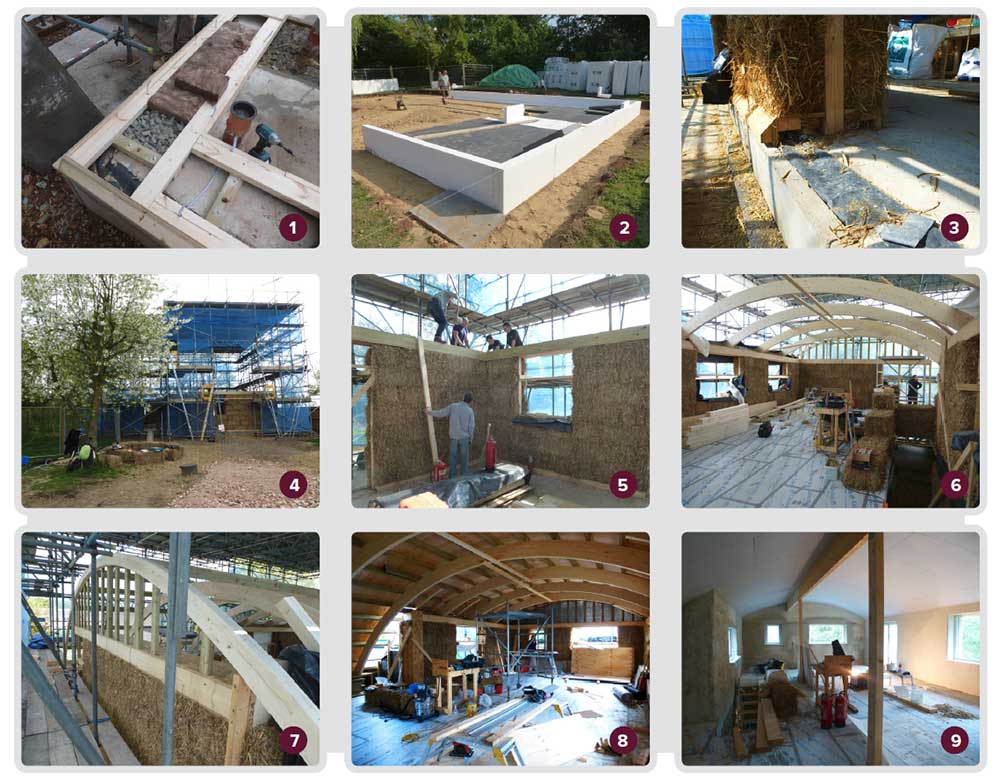

Irish company Tanner Structural Designs took care of engineering the foundations, using the Irish-made Kore passive slab insulated foundation with external ring beam and internal ribs. Builders laid the foundations, and built the garage, in late 2013. “Hilliard Tanner worked out a way of creating a base plate on top of the concrete ring beam that the straw bale builds off. It’s a good solution in terms of transferring loads down into the foundations,” says Goodman.

Finally, at the end of March 2014, volunteers arrived at Dave and Mabel’s plot of land for another Barbara Jones course and work began to construct the straw bale walls. Dave took a year’s sabbatical to work full-time on the project. Volunteers came from far and wide, including France and Sweden. The tutor was Jakub Wihan, who teaches straw bale construction for Straw Works from his base in Todmorden, West Yorkshire.

“The course lasted two weeks and we built the ground floor walls. After a gap of a few weeks Barbara Jones sent more people to help out and we got most of the first floor built. But after a month all the volunteers went home and I was the project manager,” Howorth says.

“At that point, I had to become a super apprentice of everything: carpentry, plumbing and electrics. I did have little bits of knowledge from working in a repair shop at school and doing woodwork at school and bits of DIY. But this was on another level.”

Airtightness tests revealed a final figure of 0.42 air changes per hour, well inside the passive house standard of 0.6. However, initial tests had been even more impressive.

“The initial figure was 0.29 but something happened before the building was finished. When it was depressurised the readings were fine, but when it was pressurised to get an average of the two figures, there was a leak allowing air to escape inside to out, but it wasn’t pulling it in from outside to in. But it was impossible to locate it,” says Goodman.

How the straw bale walls were built

Here’s how Dave Howorth and his team constructed the straw bale walls at Haven Cottage. First, the full ground floor walls were built by stacking straw bales onto timber stakes, and then a U-shaped timber beam was laid on top of the wall. Next, fencing wire was wrapped vertically around the walls at intervals of every two to three metres and mechanically tightened.

Several restraint straps were then attached at the top and bottom of the wall on one section (about five strap positions were used in total) and tightened as hard as possible, compressing the bales. Then the straps were taken and moved to the next part of the wall, and the whole process repeated. After going the whole way round the ground floor wall and checking everything was still tight, the wall was declared ‘compressed’, the U-shaped beam was completed (turning it into a box beam) and work could begin on the first floor using the same process.

Eventually, just before rendering began, the fencing wires were cut out, having served their purpose. The straw was fully compressed and would not rebound. Alternative methods of compression are sometimes used, such as placing tonne bags of sand on top of the wall, or using car jacks to force the tops of the bales down. “Fencing wire seemed like the easiest technique in our situation,” says Howorth. “The compression ensures that there are no gaps in the wall or within the straw, thus ensuring both structural and thermal effectiveness.”

The house has no central heating system, as such. Space heating is all provided directly by electrical heaters. There is a post-heater in the ventilation system, which heats up incoming fresh air, plus three radiant heaters fixed to walls inside the house (two in bathrooms, one in the downstairs hall).

This article was originally published in issue 25 of Passive House Plus magazine. Want immediate access to all back issues and exclusive extra content? Click here to subscribe for as little as €10, or click here to receive the next issue free of charge

The basic heating strategy in winter is to use the post-heater, and the radiant heater in the hall, to bring the temperature up to 21C overnight — this is enough to ensure it then doesn’t drop below 20C during the day.

Domestic hot water is stored in a Gledhill thermal store, which is basically a big, highly insulated bucket containing 250 litres of water. The water in the bucket is heated by two immersion heaters.

The bottom immersion – at the base of the tank – is connected to a solar diverter that takes spare power from the huge 27 square metre solar PV system whenever it is available. This is the main method of heating water. “It’s the only method we use during summer and is used part of the time in winter. The immersion’s thermostat is set to 95C to capture as much solar energy as possible and store it as hot water,” Howorth says.

Meanwhile, the top immersion – half-way up the tank – is connected to a time switch and its thermostat is set to 60C. This immersion is used as a backup to the solar power, which is why its thermostat is set lower. During winter the time-switch is set to come on for two hours during the night to provide enough hot water for the following day. If required, the immersion can also be switched on at any time for an hour by pressing the boost button on the time-switch.

At the beginning of March 2018, vicious snowstorms swept across the UK and Ireland from the east. When Passive House Plus contacted Dave Howorth to ask how the house was performing at the time, he simply said that it “just behaves as it is supposed to” — and that the temperature inside was just over 20C.

1 Installation of mineral wool full-fill cavity insulation to the insulated box beam; 2 the KORE passive reinforced concrete raft foundation; 3 the walls consist of 450mm loadbearing straw bale; 4 erection of the straw bale ground floor walls under way; 5 hazel stakes were hammered into the straw bales to secure them in place, and a timber box beam was laid on top of the ground floor wall before installation of the first floor; 6, 7 & 8 a curved ‘Dutch Barn’ style roof was chosen, in keeping with the Suffolk vernacular, though this design proved a structural engineering challenge because of the forces exerted onto the straw bale walls; 9 a horizontal beam supports the curved roof structure and internal walls were finished with a 25mm lime plaster.

He said that, in general, it was difficult to describe how the house performs. There’s not really much to say. He elaborated: “That is, [the] passive house windows keep the drafts and noise out. Passive house walls and windows, and roof and floor, keep the temperature stable so we just sit and look at it snowing outside.

“In summer we sit and look at the sun on the fields.”

Selected project details

Clients: Dave & Mabel Howorth

Architect: Good Architecture

Structural engineer: Rose Consulting Engineers

Passive slab engineer: Tanner Structural Designs

Timber roof design: Cullen Timber Design

Passive house certifier: Warm Low Energy Building Practice

Airtightness tester: Paul Jennings (formerly of Aldas)

Straw bale construction: Straw Works

Aluminium roofing: EFL - Specialist Roofing Contractors

Roof insulation: Warmcel, installed by Payne Insulation

Floor joists: Easi-joists, via Holden Timber Engineering

Insulated foundations: Kore

Windows & doors: Livingwood

MVHR: Brink, via Passivhaus Store

Thermal store: Gledhill

PV: Sunmodule

In detail

Building type: Two-storey detached straw bale dwelling, 148.3 sqm TFA with single-storey conservatory outside thermal envelope.

Passive house certification: Certified PH

Classic (PHPP 9 PER Assessment)

Space heating demand (PHPP): 14 kWh/m2/yr

Heat load (PHPP): 10 W/m2

Primary Energy Renewable (PHPP): 63 kWh/m2/yr

Environmental assessment method: N/A

Airtightness (at 50 Pascals): 0.42 ACH or 0.47m3/hr/m2

Energy performance certificate (EPC): C78

Overheating (PHPP): 6%

Heat loss form factor: 3.22

Measured energy consumption: Electricity meter readings show the house consumes on average 4,622 kWh per year, while generating on average 3,956 kWh per year from its solar PV array.

Energy bills: Based on Dave & Mabel’s average annual consumption of 2,365 kWh (day) and 2,256 kWh (night) and Powershop’s Shop for Powerpack’s tariffs of 12.4p and 7.1p respectively (as per switch.which.co.uk), the estimated average annual total energy bill works out at £512, including VAT and standing charges. According to PHPP, the house is estimated to consume 2,082 kWh per year for space heating, and because Dave & Mabel only run their electric space heaters at night (ie using night rate electricity of 7.1p), this would yield an estimated annual space heating bill of £160. (However, the house may be using far less space heating than PHPP assumes, as the total night time consumption is only marginally higher than the PHPP estimate for space heating). In 2017, Dave and Mabel received a feed-in-tariff of £627 for generating solar power in that year. Subtracting this from the calculated annual energy bill of £512 gives a net profit of £115.

Thermal bridging: ACDs not used.

Foundations: no thermal bridging through use of minimum 100mm EPS formwork to concrete ring beam; first floor: metal web joists are not built into thermal envelope; gable walls: thermally-broken double stud construction; curved roof: thermally-broken double joist construction; window/external door jambs and heads: wood fibre insulated external reveals (for lime render finish). Ground floor: KORE passive reinforced concrete raft foundation, with external ring beam and internal ribs, on 400mm EPS insulation, on 50mm sand blinding, on 550 to 750mm compacted blast furnace slag subbase. U-value: 0.081 W/m2K

Walls: 450mm nominal loadbearing straw bale, finished with 25mm nominal lime render externally and 25mm nominal lime plaster internally. Insulated box beams at first floor level and eaves level made up from timber joists and noggins, 18mm OSB flanges and full-fill mineral wool insulation. U-value: 0.114 W/m2K

Gable panels above box beams: 100 x 50mm double timber stud construction, finished with 25mm nominal lime render externally with mesh reinforcement on 25mm wood wool board, and 25mm nominal lime plaster internally with mesh reinforcement on 15mm wood wool board. Insulation: 410mm wide cavity injected with Warmcel. U-value: 0.100 W/m2K

Curved roof: Natural embossed aluminium standing seam sheeting on pro clima Solitex UM Connect underlay, on 2 x layers 9mm plywood, on 150 x 50mm timber joists, on 300 x 75mm curved glulam beams. 360 x 100mm glulam ridge beam. Ceiling construction: Gypsum plaster finish at bottom, on 9.5mm plasterboard, on Intello Plus airtightness membrane, on 6mm hardboard sheathing to underside of 150 x 50mm timber ceiling joists between curved glulam beams. Insulation: 450mm deep cavity injected with Warmcel. U-value: 0.095 W/m2K Windows: Livingwood tilt & turn triple glazed alu-clad redwood windows, lift & slide door and entrance doors, with argon filled glazing. Overall U-value: 1.00 W/m2K

Heating system: Direct electric space heating: 1.8 kW MVHR post heater (bought directly from Veab) and 1.8 kW radiant heater to downstairs hall, both only run at night on Economy 7 tariff. Two x 1.2 kW Stiebel Eltron radiant heaters in two of the three bathrooms, used for comfort when showering. Domestic Hot Water: Immersion heaters in 250 litre Gledhill Torrent Greenheat thermal store (as per detail in article).

Ventilation: Brink Renovent Excellent 300 heat recovery ventilation system with supply and extract plenums and radial ductwork; Passive House Institute certified to have heat recovery rate of 84%.

Electricity: 27 square metre Sunmodule Plus SW 250 mono black solar photovoltaic array with average annual output of ?? kW; Enphase M215 Microinverter.

Green materials: Compacted subbase used blast-furnace slag, a byproduct from steel manufacturing; straw bales supplied from an Essex farm; Warmcel recycled newspaper cellulose fibre insulation.